In the Netherlands, Safe Drug Consumption Sites Are Saving Lives. The U.S. Is Resisting.

After years of activism, the Dutch have embraced state-sponsored supervised injection sites as the standard of care for opioid treatment. Reporting from Amsterdam, our writer finds that they offer lessons for the U.S., where the war on drugs has failed to stop an overdose crisis.

| September 14, 2022

At first glance, a Dutch safe consumption site looks like any other clinic. Patients walk into a sterile medical environment and are taken to a cubicle with a sink to wash their hands. From there, they approach a metal table, where they take illegal drugs, under supervision from trained medical professionals.

Each of the more than two dozen safe consumption sites across the Netherlands provide a hygienic, judgment-free space where drug users, typically five at a time, can bring their drugs and consume them without having to worry about legal repercussions while under the care of medical staff who help minimize risk.

“Suddenly, people that are normally out on the street who are completely alone and isolated find a place where they actually have a connection,” says Roberto Pérez Gayo, a policy officer with Correlation European Harm Reduction Network, and coordinator at International Network of Drug Consumption Rooms. His research into dozens of safe injection sites has found that, besides protecting people’s lives who may otherwise overdoses, these spaces can also at their best provide other services that meet clients’ various needs in tandem: addiction, the need for housing, medical care and mental health challenges.

Safe consumption sites have helped the Netherlands reduce overdose deaths since a peak in the 1980s, and the nation has since become a global leader in the movement for safe consumption. But as overdose deaths spike more than 5,000 miles away in California, Governor Gavin Newsom just this August killed legislation that would have allowed cities to set up similar safe consumption sites.

Newsom vetoed Senate Bill 57, which would have created a pilot program allowing Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Francisco to open safe, supervised spaces for people to use drugs without violating state law. After his predecessor vetoed a similar measure, Newsom told voters during his 2018 campaign that he would be “very, very open” to safe consumption sites if elected. But in a letter explaining his own veto this year, he claimed that opening the sites “could induce a world of unintended consequences,” such as “worsening drug consumption issues.”

However, study after study has found the opposite; that offering people a safe place to use drugs can significantly improve public health. Indeed, there has never been a reported overdose death in any official safe consumption site in the world. Advocates for harm reduction in the Netherlands say the country’s experience shows the importance of working collaboratively with policymakers, law enforcement, city leaders and most importantly, local residents to create places where potentially harmful drugs can be used safely.

Machteld “Mac” Busz is Executive Director of Mainline, a quarterly magazine and advocacy organization that was founded in 1990 on the principle of harm reduction, encouraging the safer use of drugs instead of abstinence, and advocating for the treatment of addiction through a public health approach instead of incarceration.

“We know that [safe consumption is] going to prevent all sorts of infectious diseases. It improves people’s quality of life, and it reduces overdose death,” said Busz.

While the Dutch have famously tolerated cannabis use and in the 1970s decriminalized use of many hard drugs, few services existed for those seeking to consume drugs safely at the height of the crisis in the mid 80s. An estimated 25,000 people used regularly, sometimes in public, and often shared needles, which littered parks and city streets. HIV spread to as many as a quarter of the country’s intravenous drug users; overdoses were a top health concern and drug-fueled street crime was rampant.

On display in the hallway leading to Mainline’s offices is one portion of a multipart photo exhibit “House of HIV” exploring the HIV epidemic through the lens of the communities affected by it, created on the 40th anniversary of the first reported case of HIV in the Netherlands.

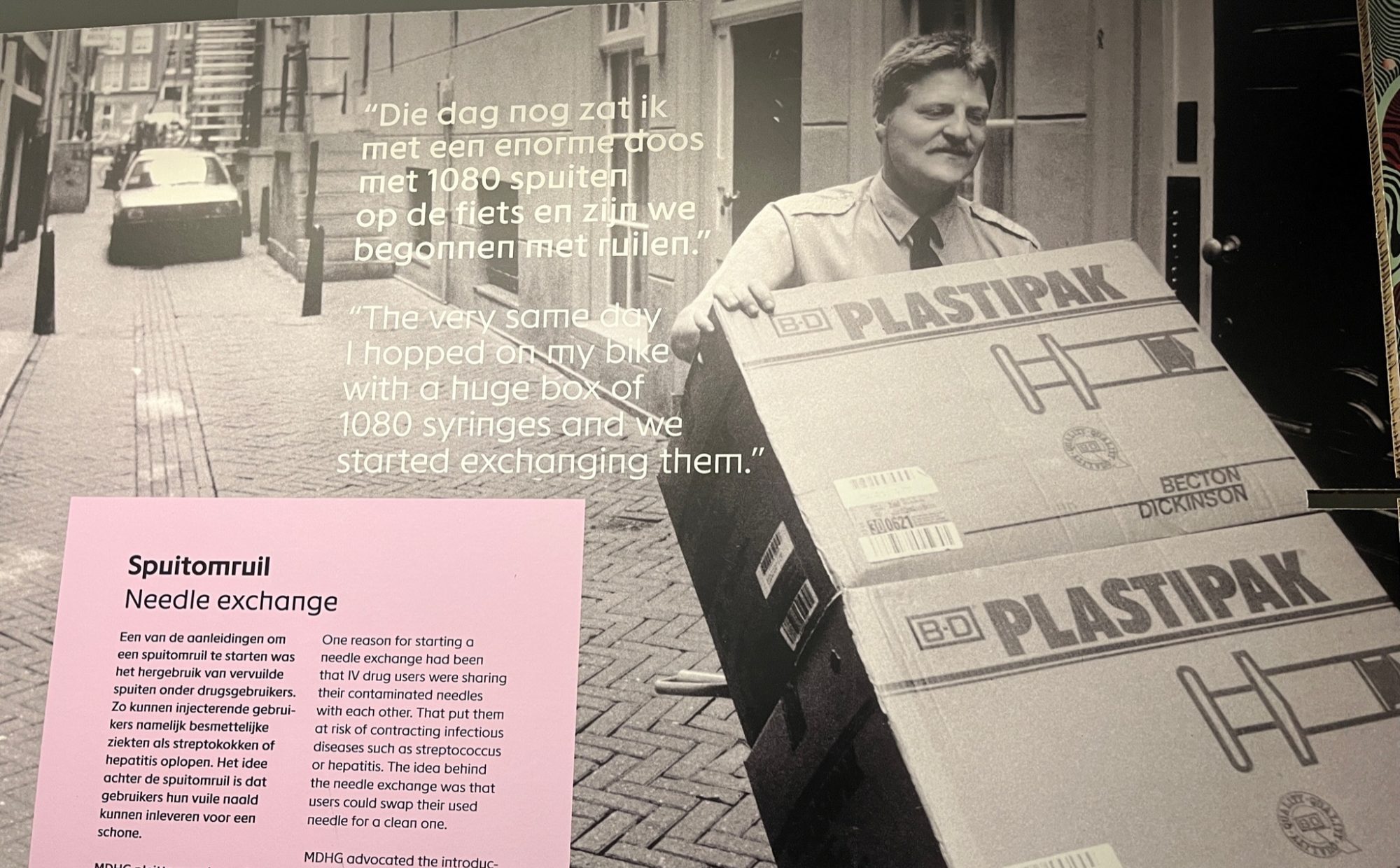

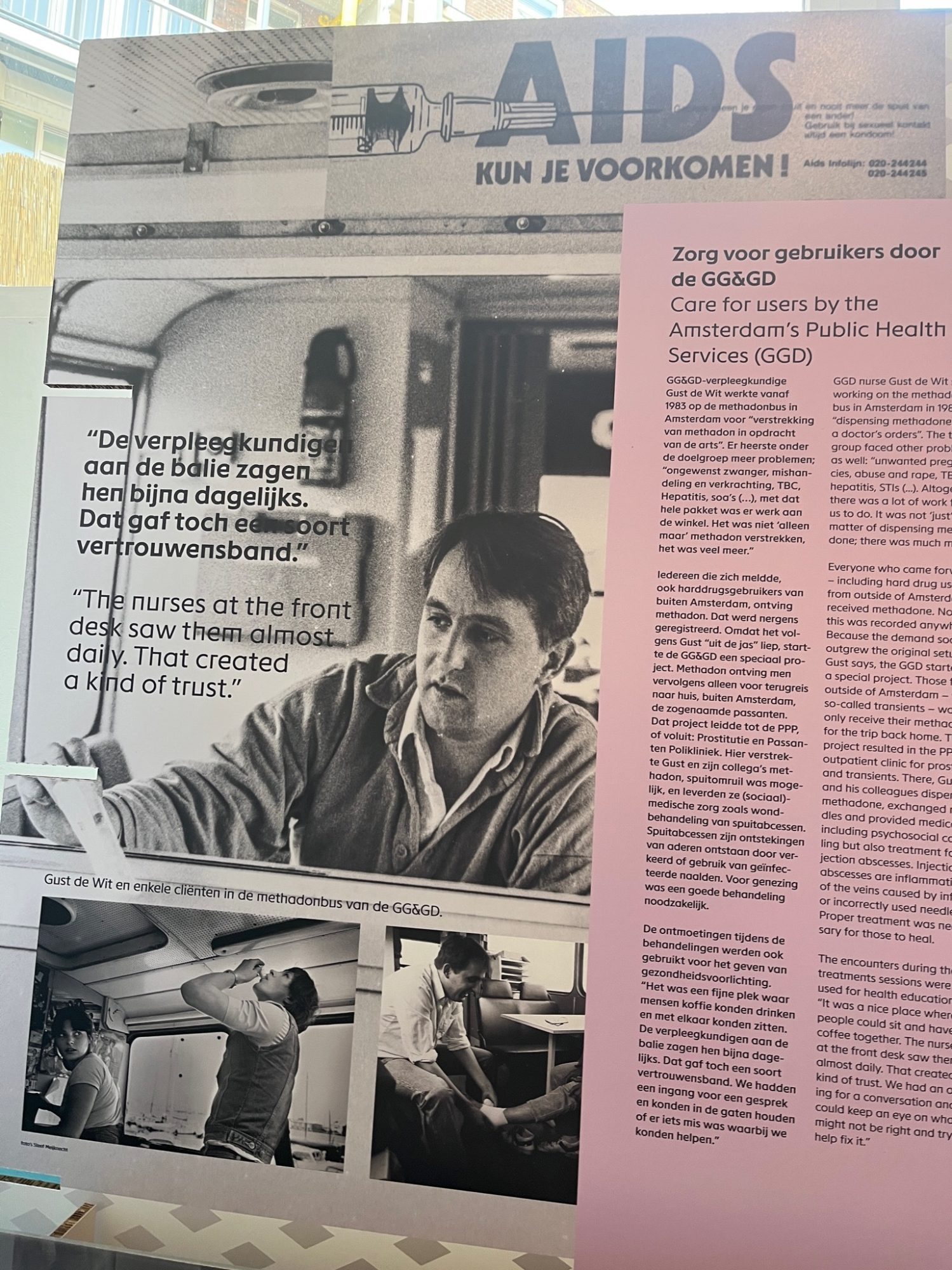

House of HIV chronicles how activists mobilized to distribute clean needles and methadone, educating users about high-risk behavior. One black and white photo shows an activist giving a police officer a copy of Mainline, part of a years-long campaign to convince officials to abandon the criminalization of addiction for a harm reduction approach. Law enforcement officials went on to become important advocates of harm reduction and safe consumption sites, Busz says.

After a decade of advocacy from organizers and lawmakers, the Netherlands authorized safe consumption sites in 1996. By 2019 there were 37 operating across 25 cities, the highest concentration in the world.

While selling drugs like heroin remains illegal today, drug users in the Netherlands are met with resources, not incarceration. The sites offer access to clean needles and alternatives to heroin, such as methadone, as well as educational materials about harm reduction, social services, housing and healthcare. Proponents say this approach is responsible in part for the Netherlands having a tenth of the overdose rate that exists in the U.S., as well as a far lower crime rate.

“People resort to crime out of necessity,” says Busz. “If people instead can access a substitution program where at least they don’t have to chase after their drugs and money anymore, that leads to a significant reduction in crime,” she says, noting studies that have shown these alternatives to incarceration are also far more cost-effective.

But it’s a mistake to think simply opening safe consumption sites can solve the opioid epidemic, says Gayo. The Dutch experience has found that these sites are most effective when paired with comprehensive social services, such as housing where consumption is allowed, and mental health support.

Some sites operate within existing housing or medical facilities that serve areas struggling with addiction. Others serve marginalized populations, such as migrants or those experiencing housing insecurity, by offering a place to foster community. Once inside, users find a space that resembles a living room with couches and tables where they can consume drugs, rest, or listen to music with others. Staffers stand by in case of emergencies and build relationships with clients.

This communal environment helps officials connect clients with medical, mental health and drug treatment as well as educational and employment opportunities.

“Each of these facilities has to be contextualized within particular communities,” says Gayo. “Drug consumption rooms work, but in order to work, we need to have a bigger conversation about how to tackle the social inequality that produces negative health outcomes in marginalized and underserved individuals and communities.”

The number of safe consumption rooms in the Netherlands has fallen as intravenous drug use decreases, with the population that continues to use these drugs aging. Experts attribute this to both the success of the educational efforts of the harm reduction movement, and shifting drug consumption habits among younger generations.

Overdose has been the leading cause of accidental death in the United States since 2017, a trend largely driven by the increased use of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is lethal even in small amounts. In California, 10,416 people died of an overdose in 2021, nearly double the 2018 death toll. And by April 2021, the national overdose death rate had climbed nearly 30 percent from the previous year, according to the CDC.

Meanwhile, the U.S. also has the highest incarceration rate in the world; 1 in 5 people behind bars are charged with drug offenses, or nearly 400,000 people, a disproportionate number of whom are Black and Latino.

The failure of mass incarceration to dissuade drug use, the growing rate of overdose deaths, and the ample evidence that safe injection sites can decrease these deaths has created a growing demand in the U.S. for a different model.

For years, an underground network of safe injection sites have operated across the country, staffed by trained personnel who risk legal repercussions. A 2020 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine reviewed data from one such unsanctioned site—whose location was kept secret by researchers—and found it averted dozens of overdoses over five years without a single fatality.

Last year, the U.S. opened its first two authorized safe injection sites in New York City. Facing a spike of overdoses during the pandemic and after years of planning, the city forged ahead with the plan without authorization from state authorities who said it required further study. They have reported averting 300 overdoses since opening last November.

Critics of safe consumption sites, however, frequently invoke images of neighborhoods flooded with drug users from across an entire region who disrupt local communities.

“Fueling the drug epidemic with drug dens and needle supplies is like pouring gasoline on a forest fire. It merely worsens the problem,” California Senate Republican Leader Scott Wilk wrote in opposition to the measure without citing any evidence to back these claims.

San Francisco is still considering moving forward with opening safe consumption sites regardless of Newsom’s veto. They would be run through local non-profit organizations in a model similar to New York’s.

“We will keep working with our community partners to find a way forward” tweeted Mayor London Breed, who has spoken about her sister’s death from an overdose and who supports injection sites. She said she was “disappointed” by Newsom’s veto. The bill was introduced by state Senator Scott Wiener, who represents San Francisco and called the veto ”tragic.”

In the Netherlands, safe consumption activists figured out how to win over critics and helped make safe injection sites accepted as a social norm. Their placement must comply with local and regional regulations, is based on where there is need, and “is negotiated with communities,” says Gayo. “Some communities feel more comfortable having a facility close to the neighborhood, and others don’t.” To avoid overcrowding and disrupting local communities, the more than two dozen sites are distributed across the country.

To succeed, leaders of the safe consumption sites must work in constant collaboration with their neighbors as well as authorities, who must be responsive to their needs, says Eberhard Schatz, a longtime researcher and harm reduction advocate.

The AMOC safe consumption site in Amsterdam consults with a neighborhood commission whose members include representatives of local neighborhoods, community centers, law enforcement and the coordinator of the consumption site.

Close coordination between these stakeholders can help decrease crime and public nuisance complaints, says Gayo.

The sites maintain a close collaborative relationship with law enforcement and local hospitals and clinics, who help connect users with the facilities and can respond in case of emergencies. “The facilities have a direct line with [first responders],“ says Gayo.

Advocates in the Netherlands offer words of support for the U.S. harm reduction movement. “These are people that are taking matters in their own hands when you have a government that doesn’t care about you and just lets you die,” said Busz, who notes the parallels between the Netherlands three decades ago and the U.S. today.

“Here the first drug consumption rooms and needle exchange programs were all led by drug users themselves in the beginning,” taking on considerable personal risk, said Busz. Government-supported drug injection sites were the result of activists proving to opponents that they can save lives without increasing crime.

Busz says the state support is critical to acquire the necessary funding for success. “With all everything that we know now and evidence base that it is there… they should be backed by the state from the start.”