Survivors of Solitary Confinement Face the California Governor’s Veto Pen

Gavin Newsom rejected restrictions that lawmakers put on his desk last year. Fueled by their own experiences in isolation, survivors are pushing him to reconsider.

| May 24, 2023

By international human rights standards, Jack Morris was tortured by the state of California for almost four decades.

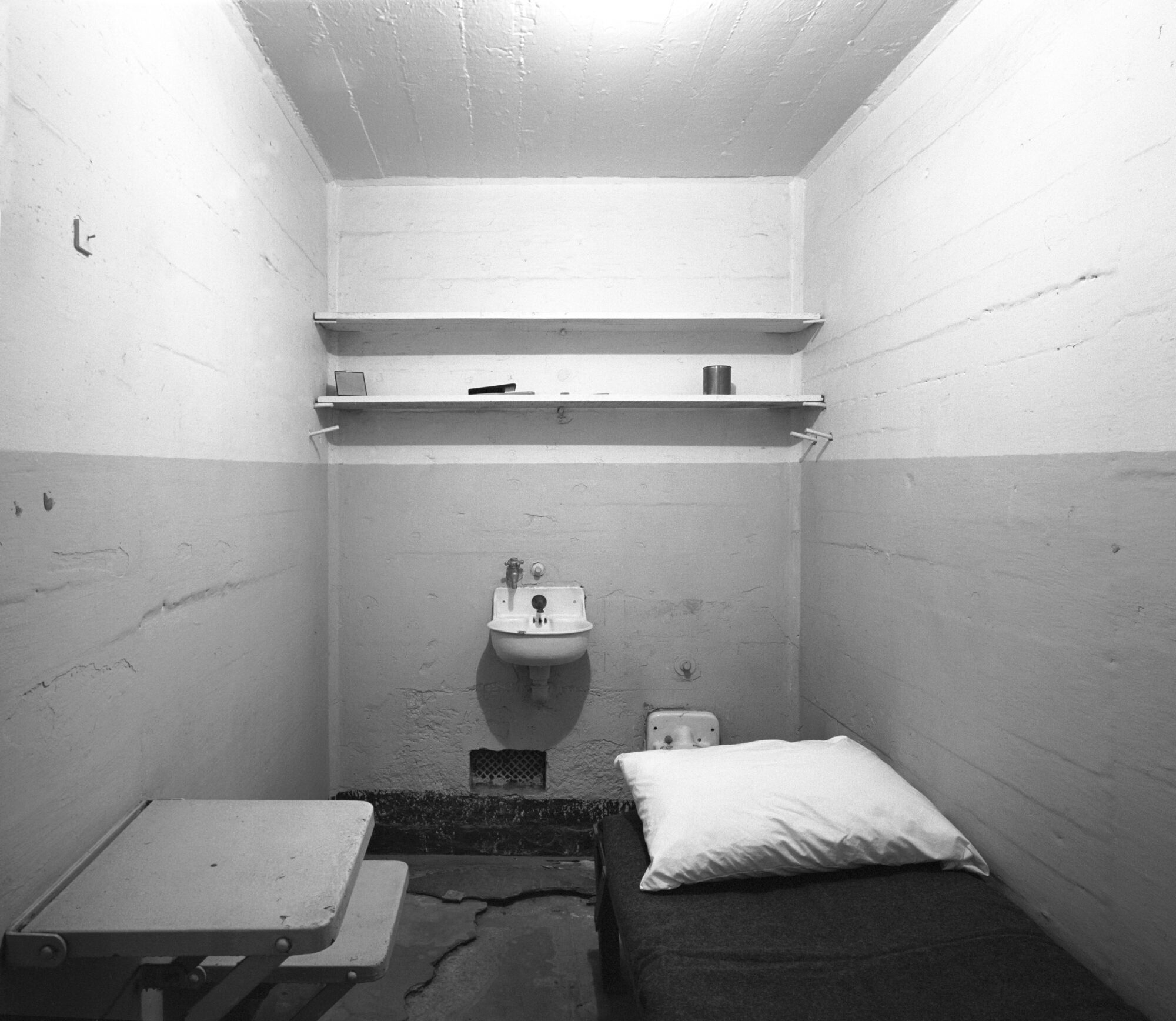

Morris mostly lived in solitary confinement from the time he went to prison in 1978, the year “Grease” was released, until he got out in 2017—alone 23 hours a day inside a cell the size of a parking space, shut off not just from the outside world, but also from the bonds and makeshift society that develop behind prison walls. He was only allowed phone calls whenever a close family member died. Over time, his sensory perception changed and small sounds made him jump. He stopped caring to watch TV, and eventually shifted from desperately craving human contact to withdrawing into himself and no longer wanting to speak with others.

“It’s a slow, torturous event that slowly deteriorates you, both physically and mentally, emotionally and spiritually, until you no longer exist,” Morris told Bolts.

In 2013, while still imprisoned, Morris took part in a historic hunger strike protesting the pervasive use of solitary confinement inside the California prison system. “We all understood that if there wasn’t something done, we would all simply die inside those cells,” he said. Pelican Bay State Prison, the supermax facility where Morris spent much of his incarceration, had around 1,100 solitary cells in its “Secure Housing Unit,” or SHU, at the time of the hunger strike, with more than 500 people confined there for over a decade. People accused of belonging to a gang could be held in solitary indefinitely. The 2013 strike, organized by four prominent gang leaders who had been isolated for decades inside the SHU, saw some 30,000 prisoners from around California participate on its first day. Some managed to stretch the protest out for sixty days and ultimately helped push the state to agree to new limits on the use of solitary confinement, like more out-of-cell time and programming.

Morris still remembers the morning the 2013 hunger strike began. It was early, and he was still lying in bed when a friend yelled through the bars and told him to look at the TV.

“I look at the ticker tape at the bottom, and right there it said on national news, ‘30,000 California prisoners on hunger strike,’ and it was—it was amazing,” Morris told Bolts. It was their third hunger strike in recent years, but this one felt different, he said, with more coordination between prisoners and allies on the outside. With the whole country watching, change finally felt possible. “We were fortunate to have litigation taking place and family members yelling at the top of their lungs on the street corner and we finally got legislators to listen when the news broadcasted that 30,000 prisoners were not gonna eat no more,” Morris said.

Last year, the California legislature took action to restrict the use of solitary confinement in the state by passing the Mandela Act, legislation that would curtail solitary beyond 15 consecutive days and no more than 45 days in a 180-day period. The bill seeks to codify the United Nations’ Nelson Mandela Rules, adopted last decade to define solitary confinement beyond 15 consecutive days as torture, so named in honor of the South African leader who spent 18 years languishing in isolation while imprisoned.

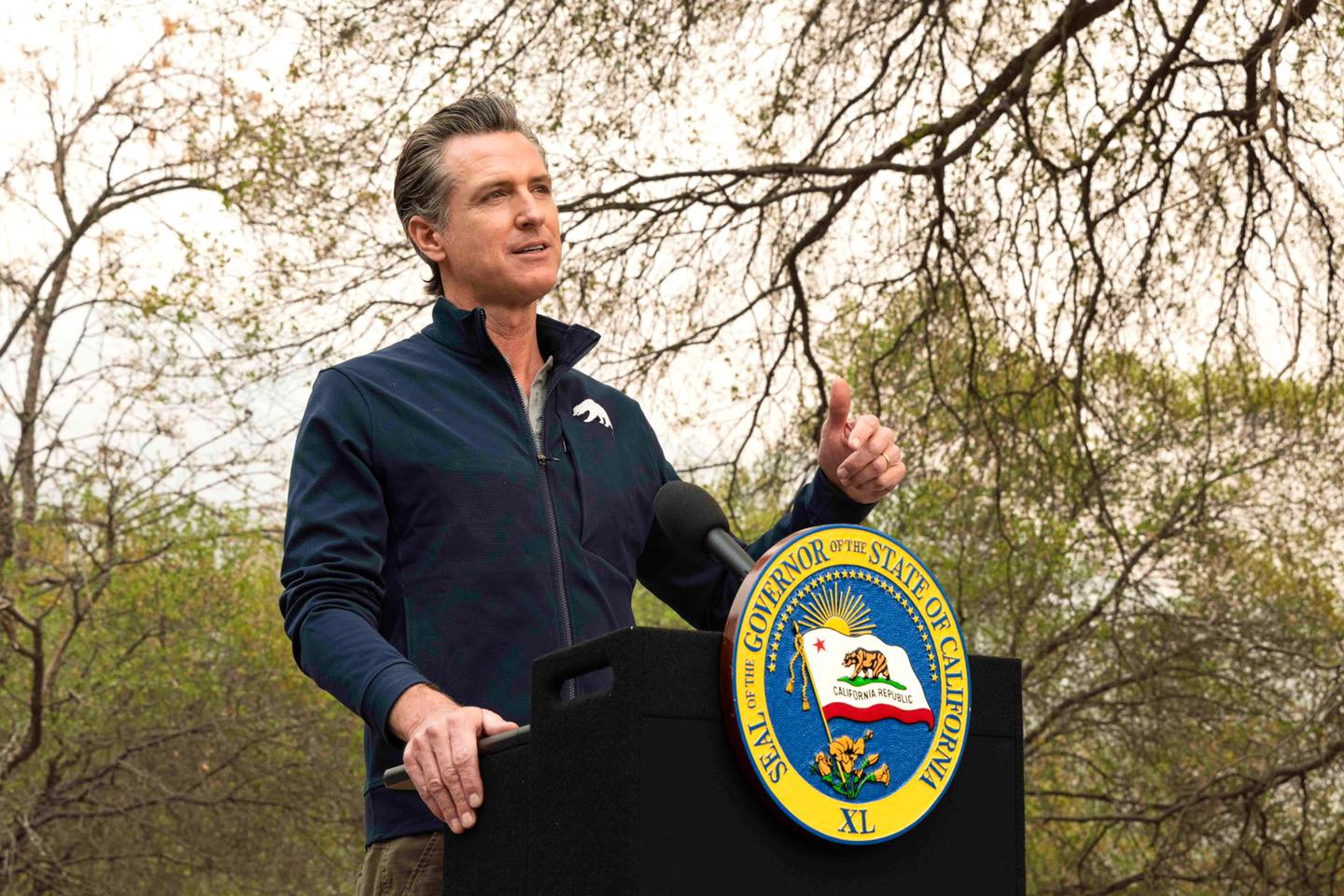

But California Governor Gavin Newsom vetoed the Mandela Act last September, arguing in his veto statement that the new restrictions “could risk the safety of both the staff and incarcerated population within these facilities.” Newsom, who acknowledged “the deep need to reform California’s use of segregated confinement,” said that he would also direct the state’s prison system, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR), to “develop regulations that would restrict the use of segregated confinement except in limited situations.”

That still hasn’t happened. CDCR told Bolts that the department merely plans to file a draft of new solitary regulations with the state by the end of 2023.

With no movement since lawmakers passed the solitary reforms last year, advocates for ending the practice—including Morris and other survivors of prolonged solitary confinement—are once again urging Newsom to support the Mandela reforms, which have been filed again for this legislative session under Assembly Bill 280.

Pasadena Assemblymember Chris Holden, who sponsored both bills, said he wants to bring California in line with international standards on imprisonment. His bill, like last year’s version, aims to end prolonged solitary in state prisons as well as local jails, which are run by county sheriffs, and immigrant detention centers, which are often run by private companies.

Holden told Bolts that he has been discussing the bill’s language with Newsom’s office and that the legislation could still change depending on what the governor supports. As written, the bill would ban the use of solitary entirely for young and very old prisoners, people who meet the state’s criteria for physical or mental disability, and those who are pregnant or recently postpartum. But Holden said that he was willing to budge on some of these categorical exclusions after Newsom’s office communicated that the governor would still not support them.

While Holden said he’s open to “reasonable” proposals from Newsom or CDCR to tweak the bill, he vowed to persist in making significant changes to solitary confinement as it is presently used. “The current system, as we speak, it meets the definition of torture,” Holden told Bolts.

Experts who have studied the decade-long movement to end solitary in California prisons say it’s unrealistic to expect CDCR, which resisted full implementation of policy changes wrought by the 2013 hunger strike, to reform the practice on its own. “Day to day, when you look at solitary confinement use, the state is still putting big numbers of people in solitary confinement for long periods of time, under new names, in new places,” said Keramet Reiter, a law professor at the University of California, Irvine who wrote a book about long-term isolation at Pelican Bay. “In practice, these institutions are just incredibly resistant to reform.”

As solitary confinement grew more controversial in recent years, California prison officials have labeled prolonged isolation “administrative segregation” or a host of other terms that have helped conceal the reality and scope of the practice. The Mandela Act seeks to cut through this obfuscation by clearly defining it: isolation without programming for more than 17 hours a day.

“What’s really interesting and almost comical if it wasn’t so horrific is the way that [authorities] and law enforcement play this like cat-and-mouse game about solitary confinement and pretend like solitary confinement doesn’t exist because they call it all these different names,” said Hamid Yazdan Panah, an attorney and the advocacy director at Immigrant Defense Advocates, which has been pushing for the Mandela reforms.

In the years leading up to the 2013 hunger strike, nearly 12,000 people were held in solitary at any given time across the California prison system. Immediately after the strike forced some changes, prisoners at Pelican Bay filed a class action lawsuit trying to end the practice of indefinite isolation for alleged gang members, who were named as such via a shadowy process called “validation” that could take as proof a person’s tattoos, clothing, or someone else’s confidential testimony. While the prison system technically re-evaluated such prisoners every six years, the plaintiffs said that there were only three ways out of isolation—snitch, parole, or die —and one of those routes, becoming an informant for CDCR, could carry fatal consequences.

That lawsuit ended in a settlement with the state prison system, which promised to end the practice of indefinite isolation and release almost all of the people in prolonged solitary confinement back into the general population. But today, though there are many fewer people in prolonged isolation than before, advocates point out that solitary confinement is still widely used in California. As of the end of April 2023, CDCR reports that 3,446 people are in some form of isolation, and that’s not counting the many people in jail or immigration detention who also find themselves in solitary.

While opponents of the Mandela Act argue that solitary is a necessary tool to protect prisoners and guards from violent individuals, advocates for ending it say isolation is imposed on an array of vulnerable people behind bars. Eric Harris, director of public policy at Disability Rights California, one of the organizations leading the fight for the Mandela Act, says isolation is often a default response to people seen as different or disruptive, including people with mental illness, physical disabilities, and gender-nonconforming people.

“When you look at folks who are often mistreated in these settings, or misunderstood in these settings, most of them have some form of disability, whether it’s been diagnosed or not,” Harris told Bolts.

It’s not uncommon for prison guards to wield solitary confinement as retaliation against people who agitate for their rights on the inside. “A lot of the folks that I’ve seen that were put in solitary were jailhouse lawyers to silence them,” Mike Saavedra, who was held in long-term isolation for over a decade, told Bolts. “They’d threaten you once you file a 602 [complaint about prison conditions] or any type of lawsuit to throw you in the hole.” Once there, he said, “they can control your litigation because now you have minimal access to the law library…you’re only allowed a small number of books.”

Saavedra, who is now the co-director of legal support at the Los Angeles-based abolitionist organization Dignity and Power Now, says he was put in isolation after he was elected to an advisory council tasked with communicating fellow prisoners’ concerns to prison leadership. “Those that got that position were typically then labeled as shot callers and sent to solitary,” he said. Undeterred, Saavedra kept filing lawsuits disputing the conditions of his confinement, as well as the validation process that kept him there.

As hard as it is to track isolation practices in CDCR, it’s even more challenging in California’s jails, which are overseen by the state’s 58 county sheriffs rather than one state department, and have no shared guidelines or metrics for the use of solitary confinement. Sacramento and Alameda counties are both under federal consent decrees owing in part to their use of solitary confinement for people in jail with mental health conditions, with the practice emerging as a focal point in last year’s election for Alameda sheriff.

The Mandela Act would make California the first state to restrict solitary confinement inside immigration detention, where it is also frequently used, and bring the practice into compliance with international standards. “They just put people back there for any reason,” said Salesh “Sal” Prasad, who was turned over to ICE for deportation after being released from CDCR custody, despite having lived in the U.S. since he was six years old. Prasad spent around four of the 15 months he was in immigration detention in solitary confinement, including a time when guards put him there “for his own protection” after his mother got COVID-19 and passed away suddenly. He never got to see her.

In solitary, Prasad found himself overwhelmed by grief, and unable to suppress a fountain of traumatic memories from his childhood. “The negative thoughts start coming in and it takes over your mind,” he told Bolts.

Isolation can also be used to quell protests inside immigration detention. Last summer, guards responded to a labor strike by Prasad and other immigrants detained at two facilities in California’s Central Valley by throwing some of them in solitary. And both Prasad and Yazdan Panah say that isolation is often employed to encourage people to give up fighting their immigration cases. “We see that time and time again—people are placed in really inhumane conditions, in part because they want to build pressure to get people to self-deport and to continue to sort of keep the conveyor belt going,” Yazdan Panah told Bolts.

Last session, Yazdan Panah said, opponents of the Mandela Act were able to sow doubt about the bill by advancing the narrative that the only two options for incarcerated people are solitary confinement or the general population. “The hypothetical that they love to give is that according to our bill, someone can kill their cellmate and the facility can put that person in solitary confinement for 15 days, and then after that, they would have to go back to the general population to ‘kill again,’” he said. In fact, Yazdan Panah said, someone who engaged in violence toward others could still be housed individually; the bill merely stipulates that the prison must increase the person’s amount of meaningful human contact and out-of-cell activities.

The bill was also hampered by high-cost estimates and the charge from detractors that it would require massive new construction across CDCR. “It’s sort of an interesting and diabolical argument because no one in California wants to expand or build new prison space,” said Yazdan Panah, whose organization has countered that the bill would only require an expansion in programming, and would save the state money in the long term.

Advocates for reform say that continuing to lean on solitary confinement only perpetuates the harms from which it claims to shield people. Reiter noted that the emotional and psychological damage that isolation engenders, especially the way it has been used in juvenile facilities, contributes to a more dangerous and volatile environment for people in prison. Harris told Bolts that no one makes it out of solitary unscarred. “Every single person that we’ve been working with who’s a solitary survivor, has said that they have some form of mental health disability, whether it’s PTSD, whether it’s anxiety, depression,” he said.

Though Prasad has been out of ICE detention for nearly six months and recently won his asylum case, he’s often brought back to those long months in isolation—the cold, the walls closing in, the smell of human beings living confined in such small spaces. “It weighs on you,” he said. “Those are four months that I can’t get back.” Prasad called his months in solitary confinement “dead time.”

As the 10th anniversary of the 2013 hunger strike approaches this summer, Newsom’s veto of the Mandela Act last year looms over discussions for how to curb solitary confinement. Advocates maintain the veto doesn’t necessarily mean Newsom won’t budge on the issue this time around, stressing increased attention on curtailing solitary both in Sacramento and around the country.

“We have over 20 states working on legislation or litigation around the use of solitary confinement, in some states even holding bipartisan support,” said Dolores Canales, the co-founder of California Families Against Solitary Confinement, who is herself a survivor of solitary confinement. Canales’ son was also in the Pelican Bay SHU during the 2013 hunger strikes.

Newsom’s office didn’t answer questions about how he’s approaching the Mandela reforms this year or whether his position has changed since last year, with a representative for the governor telling Bolts that his veto message “speaks for itself.” CDCR told Bolts that the department “anticipate[s] filing draft regulations with the Office of Administrative Law by the end of the year,” but did not respond to a follow-up question asking for more detail on the content of the regulations.

To Yazdan Panah, these promises were cold comfort. “The issue of solitary confinement has been front and center in California now for more than a decade,” he said. “CDCR has been unable—or unwilling is maybe a better term—to comply with the terms of the Ashker settlement that they themselves agreed to in 2015.” And the governor, he said, had “completely punted on the issue of jails and private detention facilities.”

Even if the Mandela Act becomes law, enforcing it will present considerable challenges. In 2021, New York’s HALT Solitary Confinement Act outlawed solitary confinement for more than 15 consecutive days, and otherwise greatly limited the practice, but today, over a year after it took effect, the law is far from fully implemented. The same year, voters in Pittsburgh overwhelmingly approved a ballot referendum to ban solitary in the county jail, which has been accused of continuing the practice in violation of the new law.

“The good that the act is doing is keeping the conversation going and the spotlight shining on them,” said Reiter. “In practice, it’s a sweeping reform that will be hard to implement and track.”

Enforcing the law in immigration detention, which is technically overseen by the California attorney general but generally operates farther outside the purview of the state, would be particularly challenging. And, as it has done again and again, CDCR could always find new ways to skirt the definitions imposed by the Mandela Act if it passes. But activists for ending solitary take the long view, saying the Mandela Act is a critical next step in their much longer fight against a tortuous and intractable practice.

“When we first got involved, I remember families used to tell us, ‘Oh, my loved one’s never gonna get out’ or ‘My loved one says nothing’s going to change,’” recalled Canales. “And I thought to myself, it has to change. And as long as we keep thinking that it’s not, that’s how it will be.”