A Police Killing Drew National Protests. At Home, a Commission Struggles with How to Make a Difference.

More than a year after Sonya Massey was killed by police in Illinois, a namesake commission has wrestled over changes that would prevent future tragedies.

| December 9, 2025

Part I: “I’m going to still try”

On July 6, 2024, the morning after Sonya Massey was murdered by a Sangamon County sheriff’s deputy, a local citizen journalist named Calvin Christian III received a mass email from the county about a deputy-involved shooting. He wrote back, asking for more information. “They usually respond, like, ‘We can’t comment further,’ anything like that, but they were just dead silent,” he told me. “So I knew something was up.”

The sheriff wasn’t speaking to reporters, and the department wouldn’t release the video of the encounter, citing a pending investigation. Word got out about the shooting immediately, though. Residents in Springfield, the county seat of Sangamon, protested one day after the next until the deputy, Sean Grayson, was fired, arrested, and charged with first degree murder. Eventually, Christian managed to obtain and publish a description of the video. But when the department finally released the body cam footage, over two weeks after Massey’s death, he was still unprepared for what he saw. “The video was—it was something that you could not describe at all,” he told me.

Around minute 14 of the footage, two sheriff’s deputies are still talking fairly civilly with Massey, a tiny Black woman in a white robe who had called to report a prowler. The interaction escalates impossibly fast. When Massey walks over to her kitchen to move a pot off the stove, acting on the deputies’ request, Grayson tells her he’s moving away from the hot water. She tells him, without evident anger, “I rebuke you in the name of Jesus.” “You better fucking not or I swear to god I’m going to shoot you in your fucking face,” he barks, putting his hand on his 9mm. “Ok, I’m sorry!” she says, cowering. “Drop the pot!” he tells her, drawing his weapon. Then he shoots her in the head. When the emergency team arrives, he says: “That fucking bitch was crazy.”

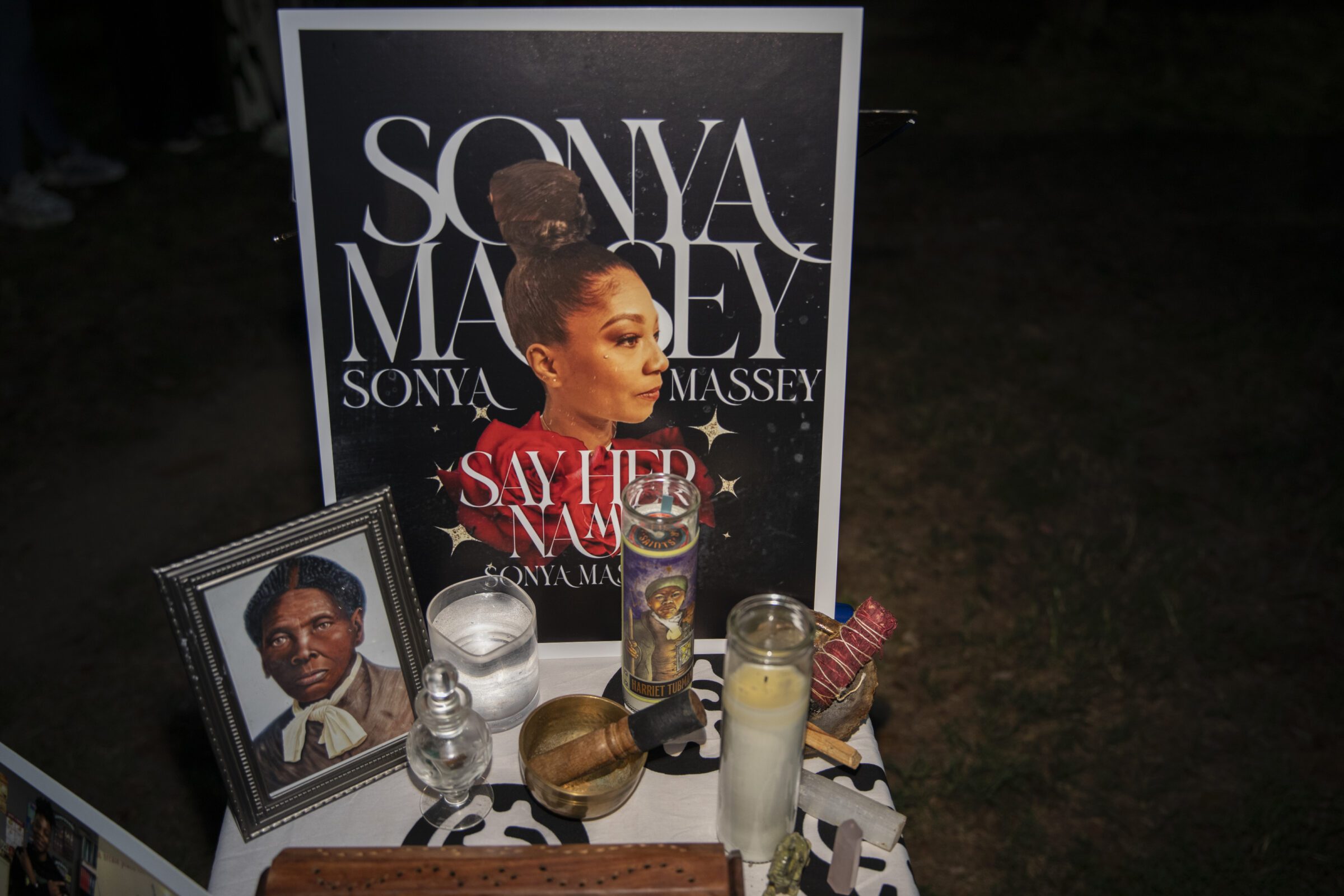

The video of Massey’s final moments shocked the country. “Sonya’s family deserves justice,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. Activists declared a national day of mourning and the U.S. Department of Justice launched an investigation. Under intense pressure, the sheriff resigned and a 24-year veteran of the Springfield Police Department, Paula Crouch, was appointed in his stead, promising reform.

Then, in mid-August, a state senator named Doris Turner and Sangamon County Board Chair Andy Van Meter, who represents Springfield, announced the creation of a citizen’s commission, tasked with addressing and improving “systemic issues in law enforcement practices, mental health response, and community relations.” Turner was a close friend of the Massey family; Sonya’s cousin Sontae told me that Sonya “looked at her as an aunt.” “I hope the Sonya Massey Commission honors her life by finding solutions to advance our community,” Turner told the public.

Over the 12 months that followed, from September through this fall, a group of volunteers—activists, former law enforcement officials, Massey relatives, clergy, and other interested locals—met regularly as members of the commission. Together, they researched and debated policy changes, working toward a final report with calls to action: a long list of demands they hoped would help transform mental health services and policing in Sangamon County to ensure that no one else would suffer the same fate as Sonya Massey.

The county had committed to funding the commission for one year—no longer. Over the course of that year, they passionately argued over what reforms might constitute real change and what were merely tweaks to the flawed systems in place. They saw some of their ideas become reality, even inspiring a statewide law. They encountered resistance and suspicion. At one point, they even feared that the commission might collapse entirely.

Subscribe to our newsletter

For more long reads on police reform efforts

Calvin Christian couldn’t have anticipated all this when he decided to apply to join the commission in 2024. He just hoped he could bring some of the experience he’d accrued battling local law enforcement over the years. “I have three daughters. I signed up to be on the commission because my thought process is that we have to change things right now for the future generation,” he told me. “It has to stop.” While watching the video, he’d been struck by the casual disrespect of the deputies’ language as they first walked into Massey’s home. It felt familiar. “A lot of the officers in this community, they talk like that,” he said. “A lot of people are even kind of immune to that, even though they shouldn’t be.”

He had his reservations: The county board, which is heavily Republican, wasn’t committing to implementing any of the commission’s recommendations. “I know a lot of people felt that the commission was just a smokescreen, that nothing’s going to be done,” Christian told me. “And I said, ‘You know what? I’m going to still try.’”

Part II: “The same moving picture shown over and over”

Every day in the United States, law enforcement kills, on average, three people. It’s an occurrence so commonplace that most of these killings fail to make a blip. Occasionally, when all the right elements align—when a shooting is caught on camera, and the video is released, and it reveals some particularly galling injustice—then the killing becomes national news.

There is a familiar choreography that these incidents follow, Sonya Massey’s killing included: In the aftermath, people scramble for solutions. The head of the department steps down; the department fires the officer; the DA files charges. The government launches an investigation; maybe the investigation culminates in federal oversight. The family files a civil suit and might receive a financial settlement, an attempt to quantify and compensate for a loss that can’t be quantified. At best, the state passes legislation.

One of those time-honored responses is the riot commission. The 1935 Harlem riot, the Watts Rebellion, the “long hot summer” of 1967, the LA uprising, Ferguson—each was followed by a commission, an appointed group often including elected officials and other interested parties, like police chiefs or civil rights leaders, that seeks to make sense of what had happened and stop it from happening again.

Historically, these commissions “act as a mechanism of evasion,” Lindsey Lupo, author of Flak-Catchers: One Hundred Years of Riot Commission Politics in America, told me. “Elected officials can sort of take all the credit for having put together this commission and receiving its report and perhaps even giving it glowing praise—and then no one’s really paying attention when they don’t act on it.”

The community suspicion around these commissions that Christian described is not a new sentiment: Flak-Catchers recounts psychologist Kenneth Clark testifying before the landmark Kerner Commission in 1967, calling the country’s pattern of launching inquiries after racial uprisings “a kind of Alice in Wonderland—the same moving picture shown over and over.” Nor is it a particularly radical one; even George H. W. Bush expressed this wariness in the wake of the 1992 Los Angeles riots, writing to a local pastor, “You know my concerns that a commission not produce yet another study no one reads.”

But Lupo also stressed that commissions serve an important democratic function. The Kerner Commission may not have led to much tangible positive change, but it is still cited today for its clear-eyed diagnosis of the pervasive inequality and racism that led to civil unrest. More recent commissions like the Ferguson Commission, established in the wake of the 2014 uprising in the St. Louis region, have allowed ordinary community members to participate in the political process in a novel way, help diagnose the injustices plaguing their communities, and have a direct say in the solutions.

Lupo stresses that she is not against commissions—“Just do it better,” she told me. Commissions can be effective, she argues, when they are given adequate funding and time—and, critically, a commitment to “continue its work in some capacity after their report is released as a way to follow up on implementation.”

This was the dilemma that Springfield resident Sunshine Clemons was grappling with in the summer of 2024 as the Massey Commission was coming together. Clemons is a veteran of the Black Lives Matter movement; in 2016 she co-founded the Springfield BLM chapter “by accident,” she said, after Alton Sterling and Philando Castile were killed by police in Louisiana and Minnesota within 48 hours of one another. “We decided to do a rally to give people an outlet, because, you know, I needed one,” she told me. “I didn’t know what to do with all my feelings and the rage.” Since then, she has continued to organize as part of the Springfield Call 2 Action coalition and served for a time on Springfield’s civilian review board, evaluating police disciplinary cases.

Clemons almost didn’t apply to the Massey Commission. She was already feeling like the civilian review board was “not set up in a way to make real change” (she eventually quit), and she worried this would simply be more of the same. But in the end, she felt she had to do it. Though Sonya Massey was the main inspiration for the commission, it was set up with two other local mental health-related cases in mind: Earl Moore, Jr., who died when two paramedics strapped him to a gurney face-down, and Gregory Small, who was seriously wounded by a local police officer after his mother called for help to deal with a mental illness episode. Small is Clemons’ little brother.

“I have advocated for all three of these people,” she told me. If there was even a chance that her presence on the Massey Commission could help change something, could advance the work she’d done with BLM and Springfield Call 2 Action to bring them justice, then she felt she had to take that chance.

Part III: “They are not sending people to jail as often”

By November of 2024, the Massey Commission was fully up and running. Each commissioner was also on one of four working groups, focusing on law enforcement, mental health services, economic disparities, and public health. Those smaller groups, which also included additional members, convened once a month somewhere in Springfield to gather facts and testimony about their topic area.

The full commission met once a month too. Their appointed meeting place varied—a library, a community center, the bottom floor of the convention center—but no matter the facility, it almost always resembled a high school gym: windowless, linoleum floors, a podium for the speaker and a few rows of folding chairs for any community members who wanted to follow along. Here, the commissioners gave updates on their working groups’ progress, heard presentations and public comment, and debated resolutions to send to the county board or sheriff. Their first official act was to send letters to state and federal officials requesting a comprehensive review of the Sangamon County sheriff’s office.

Gregory Small and Sunshine Clemons’s mother, Keena Small, joined one early meeting via Zoom to give testimony. She spoke about watching an officer, who showed up alone and didn’t appear to know about her son’s extensive history of mental illness and police interactions, shoot him four times, including once after he was already on the ground. “He yelled out, ‘Mom help me,’ and they loaded him up and drove off and then our home became a crime scene,” she told the commission. “Although he is here alive, his life is nothing like what it would have been had it been handled differently and he had gotten the care that he needed.”

Sunshine Clemons had ended up as the co-chair of the law enforcement working group. One of her main goals was to get her colleagues to consider a proposal for alternatives to policing. What if her brother, in his moment of need, had been met by a mental health worker instead of a cop with a gun?

Unarmed civilian crisis response has been in effect in some U.S. municipalities for years, but it really began to take off after 2020, with programs rolled out in major cities including Austin, Houston, and Indianapolis. In fact, after an autistic teenager was killed by police in 2012, the state of Illinois had passed its own law requiring that mental health professionals respond to mental health-related 911 calls, which should have gone into effect in 2022, two years before Sonya’s murder—but the complexities of implementing it had delayed the start date again and again, most recently to July 2027.

One of the most established programs, STAR in Denver, deploys mental health workers and paramedics in street clothes to handle mental-health and homelessness-related 911 calls instead of police. “They’re taking lots of calls,” said Alex Vitale, the author of The End of Policing and a professor of sociology at Brooklyn College who’s currently writing a report on civilian response models. (Since our interview, Vitale was appointed to the public safety transition committee of New York City Mayor-Elect Zohran Mamdani.) “They are not sending people to emergency rooms as often. They are not sending people to jail as often. And all of that is producing financial savings for these places.”

Still, as she made her pitch to the law enforcement working group to consider alternatives to police for Sangamon County, Clemons was aware that her audience included a bunch of, well, police. “We need people who understand how the system works” in the working group, she told me. “But it does, you know, it can present a challenge.”

Many of her colleagues on the working group were more comfortable with models that keep the police very involved in mental health calls, like Crisis Intervention Training (CIT), where cops learn about how to handle people in mental health crises; or a co-responder model, where therapists and social workers join police on calls. Massey Commission co-chair JoAnn Johnson, a retired state colonel with 30 years of experience who also sits on the law enforcement working group, told me that a fully civilian model, with no police involved, raised safety concerns for her. “I think it’s great if we could have licensed trained mental health professionals or even citizens that are not necessarily licensed clinical social workers,” she said. “But I also was like, ‘Well, what happens if that situation goes from nonviolent to violent?’”

But Springfield already has both CIT training and a co-responder arrangement. Clemons wanted something new—something they’d never tried before.

Part IV: “The county is not going to do anything”

“My family sent me here today to leave this commission and take our name with it,” Sonya Massey’s cousin Sontae told the room. It was February of this year, nearly two hours into the commission’s sixth monthly meeting, and Sontae, the Massey family’s only remaining representative on the commission, appeared to be expressing a fundamental lack of faith in its efforts.

The Massey family is large and tight-knit. In the months since Sonya’s death, Sontae had become something like their “unofficial translator,” holding regular calls with his aunts and uncle, whom he called the family’s “board of directors,” hearing their concerns, and triangulating between them and the commission. From the beginning, Sontae told me later, his relatives had been worried that the commission might be more performative than practical: “Is this going to be a big group talking session, or is there actually going to be some things involved that’s going to make some substantive change?”

“We didn’t want our name to be used as a political vehicle,” he said.

As the Masseys watched over the months that followed, their early skepticism seemed borne out by a series of political disappointments. In January, the federal civil rights investigation triggered by Sonya’s murder had culminated in a quick agreement that the sheriff’s department would undergo two years of federal monitoring, with no admission of wrongdoing. It wasn’t nothing, but it wasn’t a consent decree either, and many onlookers suspected Biden’s DOJ had cut corners in its haste to wrap up the process before Trump took office.

Plus, that same month, the county board had rejected one of the commission’s first resolutions—a proposal to establish a recall pathway for the sheriff. The Massey commissioners hoped it would keep the office beholden to the community year-round, not just when the sheriff came up for reelection. The GOP-led board contended that counties in Illinois do not have the constitutional power to initiate recalls and voted it down on partisan lines, 7 to 19, even after Sonya’s mother, Donna Massey, appeared to argue on its behalf.

That commission meeting in January also featured a long presentation about the state’s existing Crisis Intervention Training program, where instructors with the Illinois law enforcement training board coach police on how to interact with people experiencing episodes of mental illness. During public comment, a local activist named Ken Pacha came up to the podium and made a damning observation: Massey’s killer had gone through the training himself.

“Here we are making more recommendations for the same programs that did nothing,” Pacha told the commission. “Sean Grayson had 40 hours of Crisis Intervention training—and what did that lead to?”

Pacha spoke passionately, but he was one of only two commenters from the community. The January meeting was sparsely attended, with fewer than 10 people in the audience, including Donna Massey. “We have very low turnout at our meetings that are open to the public,” Clemons told me. “A lot of people are like, ‘Why bother going? The county is not going to do anything.’”

Tom Davis, a retired lawyer who was not on the commission but had been attending the law enforcement working group meetings, felt the commission had let go of the recall idea too easily. A onetime prosecutor, Davis’ views on policing had changed dramatically following an instance of police brutality against his son, who has autism. He was frustrated by what he perceived as a lack of transparency, with community members forced to wait until the end of official business to weigh in, and no chance to weigh in on drafts of the two main reports before the commission released them. “The public cannot ask questions—we can only comment,” he told me.

That sense of anger and futility boiled over at the commission’s February meeting, which was partially devoted to gathering community input. Person after person spoke about how few Massey family members were on the commission, about the presence of law enforcement, which felt to some like co-optation. “Sunshine and Sontae are the only people that really mirror our community,” one resident said. He felt like the focus on mental health was distracting from the underlying problem: cops. “Nobody out here is saying we don’t need police, but we need alternatives,” he told the crowd.

Calvin Christian’s youngest daughter was born the day before the meeting, but he followed along on the livestream. “They were very, very angry, and I agree 100 percent with them,” he told me later. “We’re trying to speak out for change, and we’re just steady getting roadblocked from each and every different angle with the elected politicians.”

When Sontae Massey took the mic, he spoke about the gulf between the tremendous attention his cousin’s death had garnered and the lack of change her family had seen in its wake. He told the crowd he agreed with everything they had shared. Then, at the end of his time, he said something surprising: He had decided to stay on the commission after all.

It had not been easy to convince his relatives to give the commission another chance.“I really fought my family on it, because I believed in the Massey commission,” he told me later. But in the end, they had given him their blessing.

“I’m a Springfield kid,” he told the crowd that day. “I’m not going anywhere and I’m here to fight.”

Part V: “This type of thing doesn’t have to happen, I know it in my soul”

The February meeting hit commission co-chair JoAnn Johnson hard. In addition to being a police veteran, Johnson is a Black woman. At an initial listening session run by the DOJ over the summer, she had surprised herself by speaking up. “I have Black daughters, I fear for them,” she remembers saying, “like I don’t think many of my [law enforcement] colleagues fear for their children. And I know that this type of thing doesn’t have to happen, I know it in my soul.” The deep-rooted mistrust and antipathy toward police expressed at the meeting jarred her. “I just felt impassioned to try to explain, like, ‘Yes, this is what I did. Law enforcement is what I did, but it doesn’t mean that I don’t see the same injustices that you see,’” she told me.

Johnson and her co-chair sat down privately with Sontae Massey to figure out what had gone wrong, and then set up a Zoom meeting with his extended family. Aunts, uncles, and cousins called in from Detroit, Dallas, Missouri. “We wanted to make sure that we shared with them everything that had transpired to that point, everything that we were envisioning forthcoming,” Johnson told me.

Sonya’s relatives had felt out of the loop, and the call helped. There had been vacancies on the commission after a few members, including another one of Sonya’s cousins, had stepped back, and it belatedly added new members, both Black women: a veteran racial justice activist and a young community advocate.

Meanwhile, the law enforcement working group continued to debate alternatives to policing. In April, Clemons solicited presentations from Vitale along with representatives from STAR, the Denver mobile crisis response unit.

Vitale is unequivocal that models that keep the police involved, like the CIT and co-responder models, don’t produce meaningful results, and he told the commission as much. “It is the police that destabilize the encounters,” he told me later. “It’s the presence of an armed police officer who is associated with forced arrest, forced hospitalization and use of force, and not conducive to a de-escalated, clinical kind of intervention.” During the conversation that followed his presentation, he noticed that even those members with a law enforcement background seemed very open to his argument.

It was clear that Clemons was making progress on convincing people to look toward a civilian response model like STAR. “I genuinely believe that if we had a program like that here in Springfield that had been able to respond to Sonya Massey, I believe that she would be alive,” she told the full commission while reporting back about the presentations.

The commission’s six-month report proposals didn’t yet include an unarmed civilian response team that would handle calls instead of police, but that was still on the table, and Clemons was hopeful about getting the recommendation into the report’s final version. When we spoke in April, she also noted that there had been better community engagement at recent meetings: “As we’ve been able to build the community’s trust a little more, they’re more willing to come out.” That the Massey family had publicly endorsed the commission’s work had helped tremendously. People had started to see them as independent, not just the county government’s puppet.

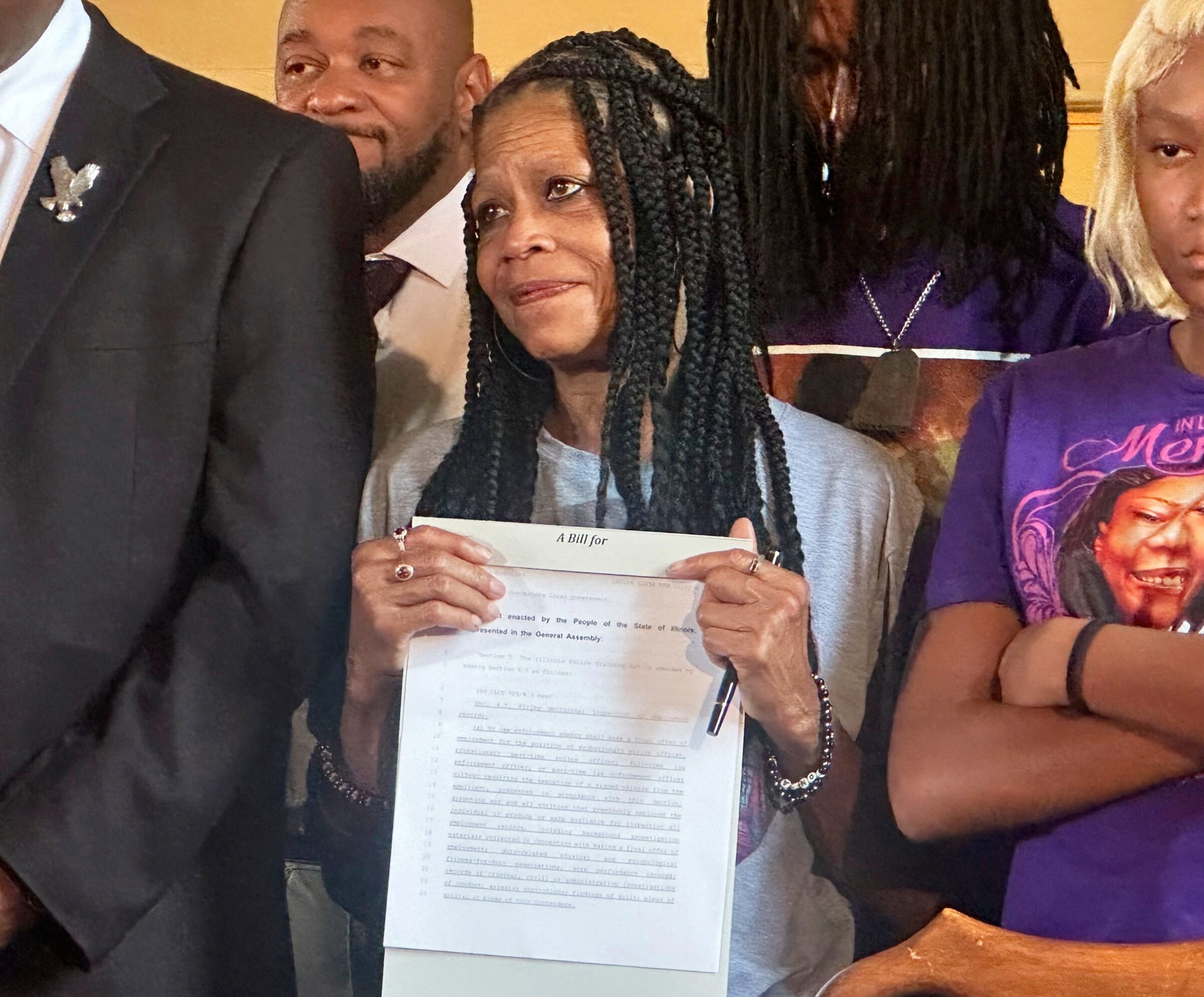

Commission members got another boost in February when Turner, the state senator who had set up the Massey Commission, introduced a bill inspired by their deliberations.

Early on, the commission had asked the sheriff’s department to implement more comprehensive background checks and bar applicants with a history of serious misdemeanor convictions. In the four years before he was taken on by the Sangamon County sheriff, Grayson, Sonya’s killer, had done stints at six different police departments; he had a history of on-the-job misconduct complaints and off-duty DUIs.

Turner’s bill built on the proposal to mandate more intensive background checks for all law enforcement officers in the state. By August, the bill was passed by the legislature and signed into law as the Sonya Massey Act by Governor JB Pritzker. “Communities should be able to trust that when they call the police to their home, the responding officer will be well-trained and without a history of bias or misconduct,” Pritzker said.

Sontae Massey saw the law as proof of the commission’s ability to effect tangible change. “It’s a very good beginning,” he told me.

At the same time, commission members remained aware of the limitations of their power to change all policing practices in the area; after the county dismissed the sheriff recall idea, Turner turned the proposal into another bill, but it stalled in the legislature. The Springfield Police Department had plenty of problems of their own, but they were outside its purview. The DOJ’s monitoring agreement only included deputies who walked a beat, like Grayson; it didn’t touch violence or neglect within the county jails.

Clemons remained dubious about the strict year-long timeline the board had imposed for the commission. Over the summer, she told me, “we’re just now really getting our footing under us—and now it’s almost time to stop.”

Part VI: ‘Keep this thing going”

On Oct. 29 of this year, Sean Grayson was convicted of second-degree murder for killing Sonya Massey. He was acquitted of the first-degree murder count; such convictions for on-duty killings are extraordinarily rare and have only occurred under unique circumstances. Even as it was heralded by some, the trial’s outcome left the Massey family and the broader community angry. “People are feeling like it’s compromised justice and not full justice,” Christian told me. “It was almost like two very big emotions crashing into each other,” Clemons told me—relief that Grayson didn’t get off scot-free, combined with a deep feeling that the verdict didn’t honor the gravity of his crime.

The commission’s final public meeting was Oct. 27, the same day the defense rested its case in the Grayson trial. After weeks in the courtroom having to view graphic footage of his cousin’s final moments and hearing attorneys argue that she was a deadly threat to the deputies, Sontae Massey felt raw. He pleaded for the committee to not let the final report constitute the end of their work, saying: “I am humbly asking everyone in here to keep this thing going.”

Clemons was wearing the same purple T-shirt in honor of Sonya that she usually wore to meetings. “I was very vocal in the beginning that I did not have faith in this commission,” she told the audience, struggling to maintain her composure. “I wanted to make sure that on the back end I also say I believe that we really have put something forth that will make our community better.”

Next, Johnson read aloud the commission’s 26 calls to action, one by one. They ranged from symbolic gestures—requesting the installation of a commemorative plaque—to ambitious policy aims: urging the Illinois state legislature to enact qualified immunity reform. Some were law enforcement-specific, like the establishment of a civilian review board with subpoena power, the gold standard for such boards; others having to do with housing, workforce training, and transit aimed to tackle the root causes of inequality that led to deadly police encounters. “We don’t solve these type of problems in a year,” Sontae Massey told me. “We’ve got things mapped out for 10 years at least.”

Clemons had succeeded in getting the proposal for a county-wide civilian-led crisis response team into the final report produced by the law enforcement working group. They decided to call it GEMSS, Guided Engagement for Mental Health and Supported Services, which also incorporates the first and last initials of Small, Massey, and Moore. But when the commission-wide final report synthesizing all four working group reports was published on Dec. 4, GEMSS wasn’t included. The language around crisis response involves expanding parameters for who can become a crisis responder to bring in more people with personal experience dealing with mental health crises. It also calls for establishing an integrated cross-county crisis response and dispatch system and creating a pilot program, but doesn’t propose removing police from calls.

The individual working groups will also be published, which Clemons told me in an email she supported, “so that the full measure of our work can be absorbed.” She also pointed to a parallel program that seemed promising: At the end of October, Springfield had announced its own opioid and mental health response pilot, BEACON, to be paid for with funds from national opioid settlements. The program will deploy behavioral health workers, fire department EMTs, and—when deemed necessary—police; it’s part co-responder model, part civilian crisis response. “The whole purpose of the BEACON project is to get the Springfield Police Department away from the non-violent mental health calls that we’re getting,” Springfield’s Director of Community Relations, Ethan Posey, told me. The goal is to roll it out next summer.

The commission members I spoke with see the final report as a beginning rather than an end. But with the county board having declined from the beginning to commit to enacting its recommendations, and a number of the calls to action contingent on the actions of other governing bodies like the state legislature, it’s not at all clear what will happen next. “The whole issue is whether or not there’ll be compliance and acceptance of all of these recommendations,” Tom Davis told me. Davis remains concerned about what the future may hold, but despite his procedural criticisms, he ultimately felt the commission had been successful: “They kept their eyes on the prize.”

A spokesperson for the county did not answer requests for comment on how the board intends to respond to the report, nor did board chairman and Massey Commission co-founder Van Meter.

Christian told me that he will only consider the commission’s work a success if all 26 calls to action are implemented, a view echoed by his peers. “We don’t want this report to go sit up on someone’s bookshelf in their office and gather dust,” Johnson told me. “We want this to be a living document—a blueprint.”

She was under no illusions about the challenges that lay ahead. “It’s going to take us holding the decision makers’ feet to the fire,” she said. But a recent development had her hopeful. A couple of weeks earlier, a new group hoping to carry the work forward by putting pressure on lawmakers to implement the calls to action had announced its formation. Calvin Christian would be involved; so would Raymond Massey, Sonya’s uncle, and a number of community activists who had been vocal at Massey Commission meetings. It would be called “People United for Reform, Power, Liberation, and Equity”—PURPLE, for Sonya Massey’s favorite color.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.