South Carolina Supreme Court Recognizes that Privacy Rights Protect Abortion Access

The ruling is the first time since Dobbs that a state supreme court has struck down an abortion restriction on state constitutional grounds.

Quinn Yeargain | January 6, 2023

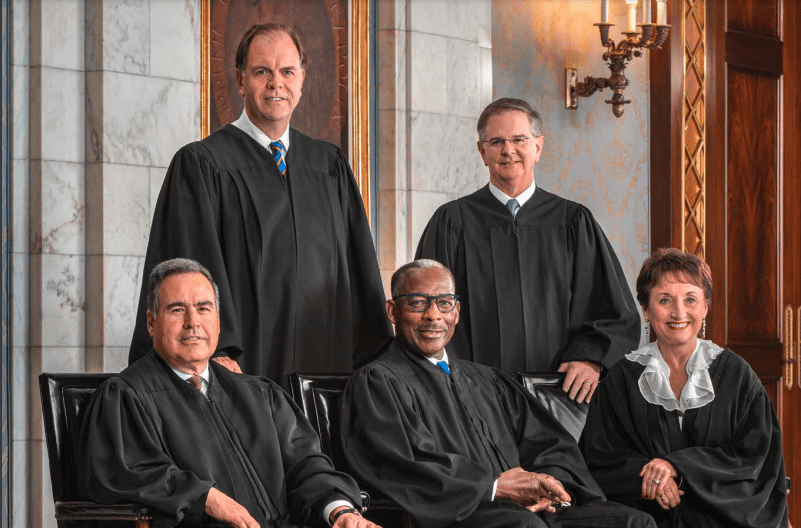

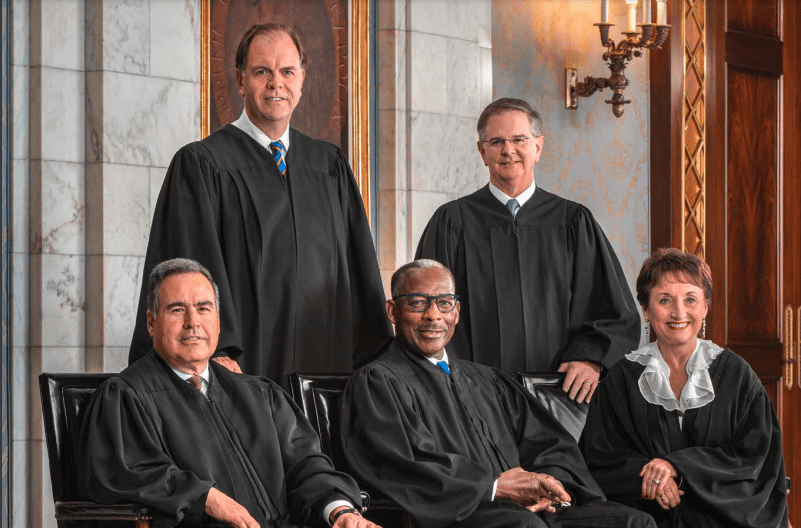

In a 3–2 decision on Thursday, the South Carolina Supreme Court struck down the state’s ban on abortions after six weeks, ruling that it is unconstitutional because it violates the state’s right to privacy.

“We hold that the decision to terminate a pregnancy rests upon the utmost personal and private considerations imaginable, and implicates a woman’s right to privacy,” Justice Kaye Hearn wrote in the lead opinion, pointing to language embedded in the South Carolina Constitution.

The six-week ban was passed in 2021 by the Republican legislature, which saw it as an invitation for the U.S. Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade. After the court’s Dobbs ruling in June, the ban briefly came into effect until the state supreme court blocked it in August. At the time, the justices left unresolved whether they thought that the law violated the state constitution’s privacy-rights protection—but they settled that question with their ruling this week.

The ruling is fragile since one of three justices in the majority is leaving the court next month, and another must retire by 2024. But advocates for abortion rights were quick to cheer the ruling, the latest showcase of the extraordinarily heightened stakes of state courts since last summer.

“The court’s decision means that our patients can continue to come to us, their trusted health care providers, to access abortion and other essential health services in South Carolina,” Jenny Black, the president of Planned Parenthood South Atlantic, one of the plaintiffs in the case, said in a statement on Thursday.

After the Dobbs decision overturned federal protections for abortion and triggered bans around the country, abortion rights advocates turned to state courts, asking them to shield abortion access by affirming it as a right under their state constitutions. States are required to abide by the minimum protections recognized by the U.S. Constitution, but their courts are free to recognize a greater level of protection—and more rights—based on state constitutional provisions.

The ruling from the South Carolina supreme court marks the first time since Dobbs that a state supreme court has rewarded that strategy and struck down an abortion restriction on state constitutional grounds.

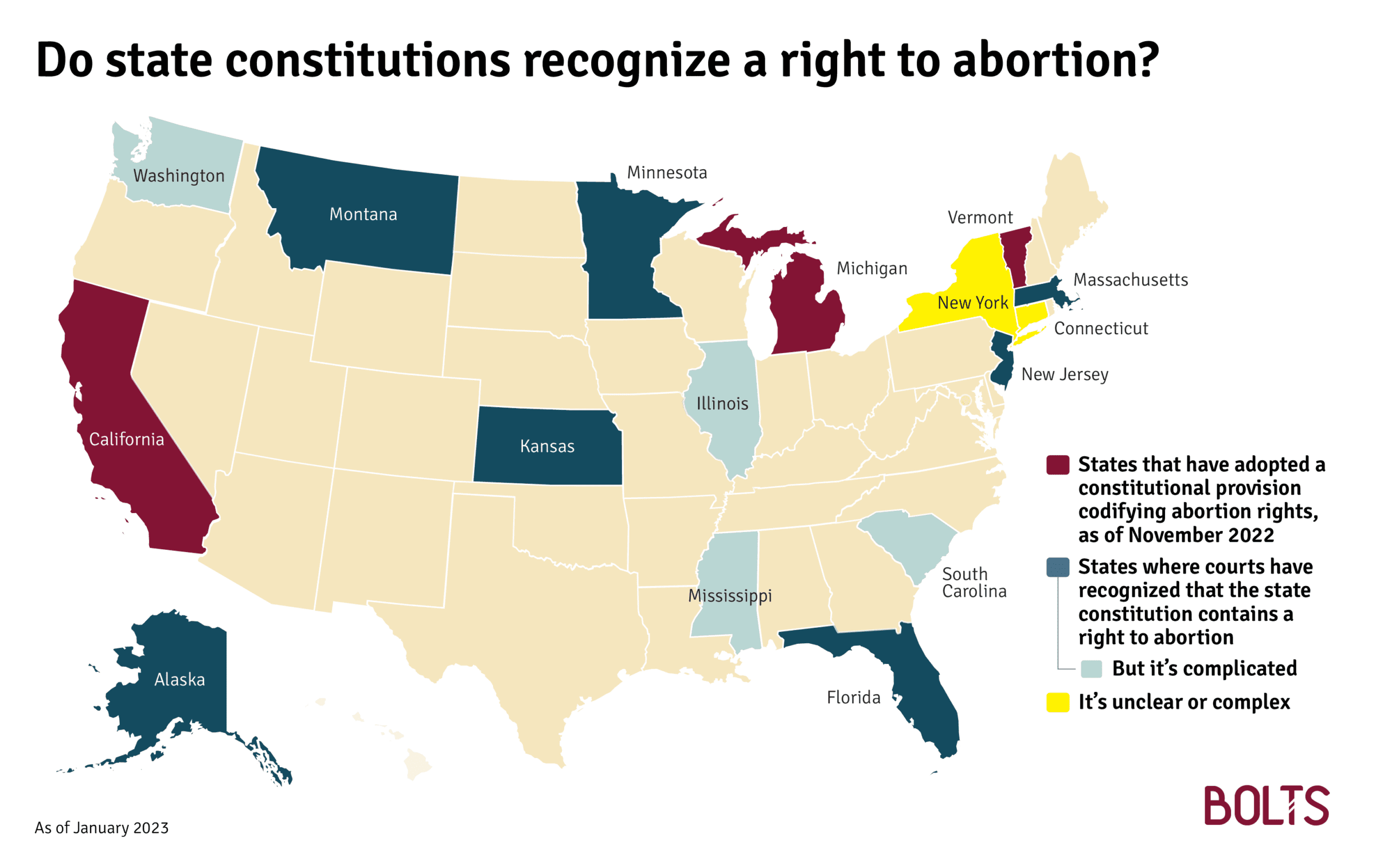

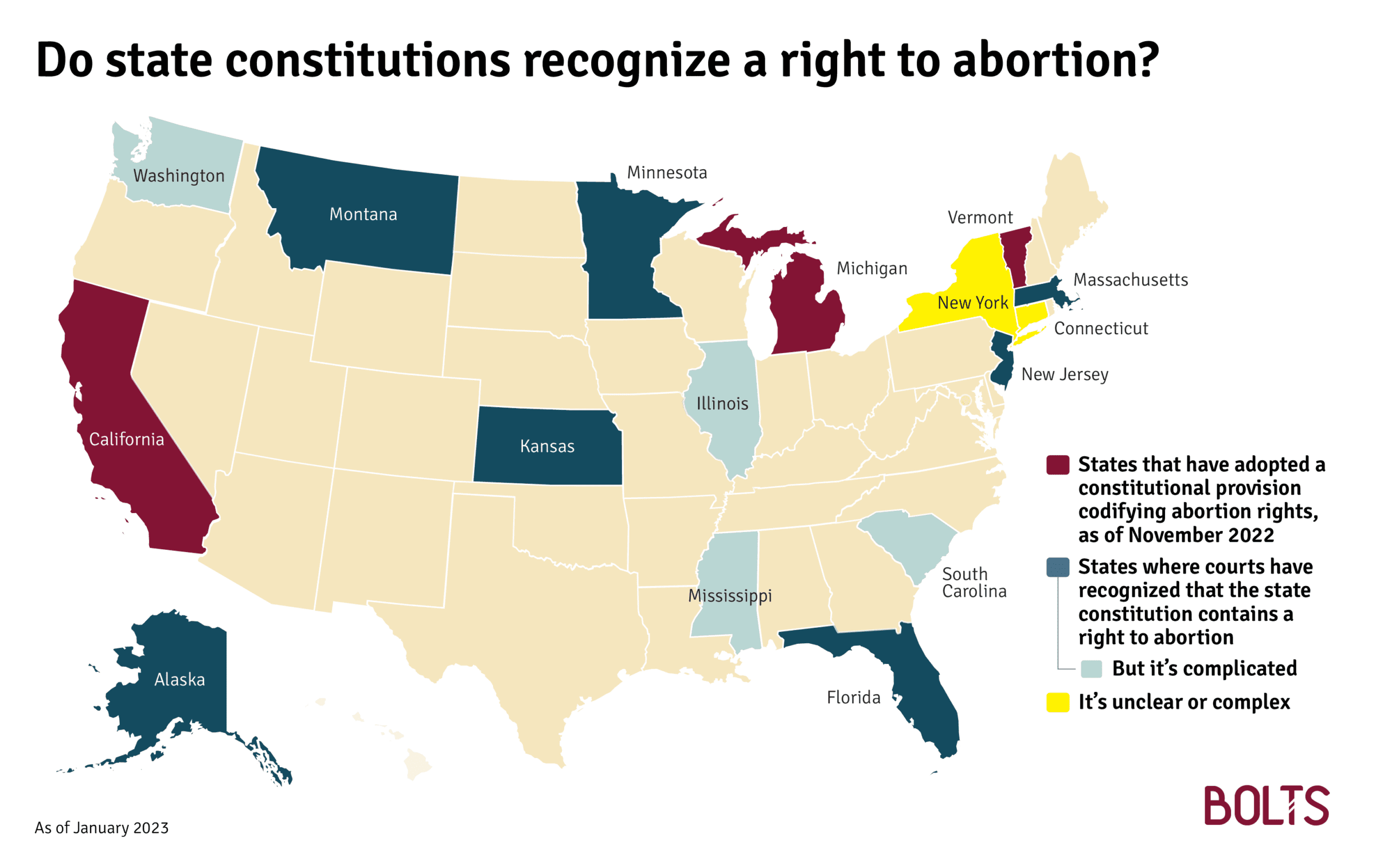

A dozen supreme courts had already affirmed by 2022 that their state constitutions recognize abortion rights, a state-by-state analysis by Bolts found in July. These rulings, like South Carolina’s, relied on interpreting language like an equal protection clause and privacy protections. In August, Kansans voted down a measure that would have overturned such a ruling; in November, voters in California, Michigan, and Vermont approved referendums that added explicit protections for abortion rights into their constitutions, becoming the first states to do so.

The South Carolina Supreme Court flirted with that step on Thursday, though whether it actually affirmed a constitutional right to abortion is a matter of some confusion—even to its own members. Two of the justices in the majority wrote that the state constitution contains the right to an abortion. But the third, Justice John Few, took pains to distance himself from that conclusion, even while writing that abortion access falls under the constitution’s right to privacy. Justice John Kittredge, in his dissent, notes that Few’s opinion is “less clear, at least to me.”

Those nuances do not change the immediate fate of the 2021 law, said Jace Woodrum, executive director of the ACLU of South Carolina.

“Although it is rare for… all the justices to write separately, the result is the same: the Legislature’s six-week ban is struck down as unconstitutional, and abortion in South Carolina remains legal up to 20 weeks,” he told Bolts.

In other states, lawsuits appealing to the state constitutions have seen some initial success but few courts have reached final decisions. On Thursday, though, the Idaho Supreme Court held that its state constitution does not protect abortion. The conservative court handed down an opinion steeped in originalist philosophy that concluded “the relevant history and traditions of Idaho show abortion was viewed as an immoral act and treated as a crime.”

The South Carolina court’s ruling hinged on interpreting the state constitution’s clause against “unreasonable invasions of privacy.” That provision, embedded in its Declaration of Rights, generally relates to “searches and seizures,” and so opponents of abortion in South Carolina argued that the protection is limited to the context of criminal procedure. But the state supreme court on Thursday rejected this argument, holding that this right to privacy applies to abortion even if “the words used do not specifically mention medical care or bodily autonomy.”

Because the six-week ban “leav[es] no room for many women” to exercise their choice to continue a pregnancy, Hearn wrote, it “prohibits certain South Carolinians from making their own medical decisions.” This “cannot be deemed a reasonable restriction on privacy.”

Hearn also drew on a broad history of privacy-rights protection in the United States to make that case, including the decisions of other state supreme courts, including Alaska, Florida, Minnesota, Montana, and Tennessee, that also applied the right to privacy to abortion rights.

The majority’s decision came with limits, though. Hearn’s lead opinion states that the abortion right protected by the state constitution “is not absolute.” It emphasizes that a six-week ban limits abortion access “before many women . . . even know they are pregnant” and “severely limits” or “completely forecloses” its availability. And Few’s concurrence outlines seemingly weaker standards of scrutiny and pushes against the notion that the right to seek an abortion is “fundamental” in the state constitution. These leave open the possibility that the same justices would uphold other types of abortion restrictions in the future.

Still, Woodrum, of the ACLU, said the differing opinions that make up the majority are a sign of strength for the position that abortion bans are unconstitutional. “There are many different paths to take that arrive at the same conclusion.”

“There is no doubt in my mind that some of our legislators will respond to this decision with more misguided attempts to ban abortion,” Woodrum said. “For months last fall, some legislators attempted to pass a complete ban on abortion, arguing that even the extreme six-week ban wasn’t enough. They weren’t successful, but we remain concerned that some of our elected officials will continue to ignore the Constitution and push to limit the reproductive rights of South Carolinians.”

Plus, the court’s composition will soon change, which could also change its approach to abortion rights. Hearn, who wrote Thursday’s lead opinion, is leaving the court in February because she has reached the mandatory retirement age of 72. Chief Justice Donald Beatty, who joined her in the majority, must also retire within the next two years.

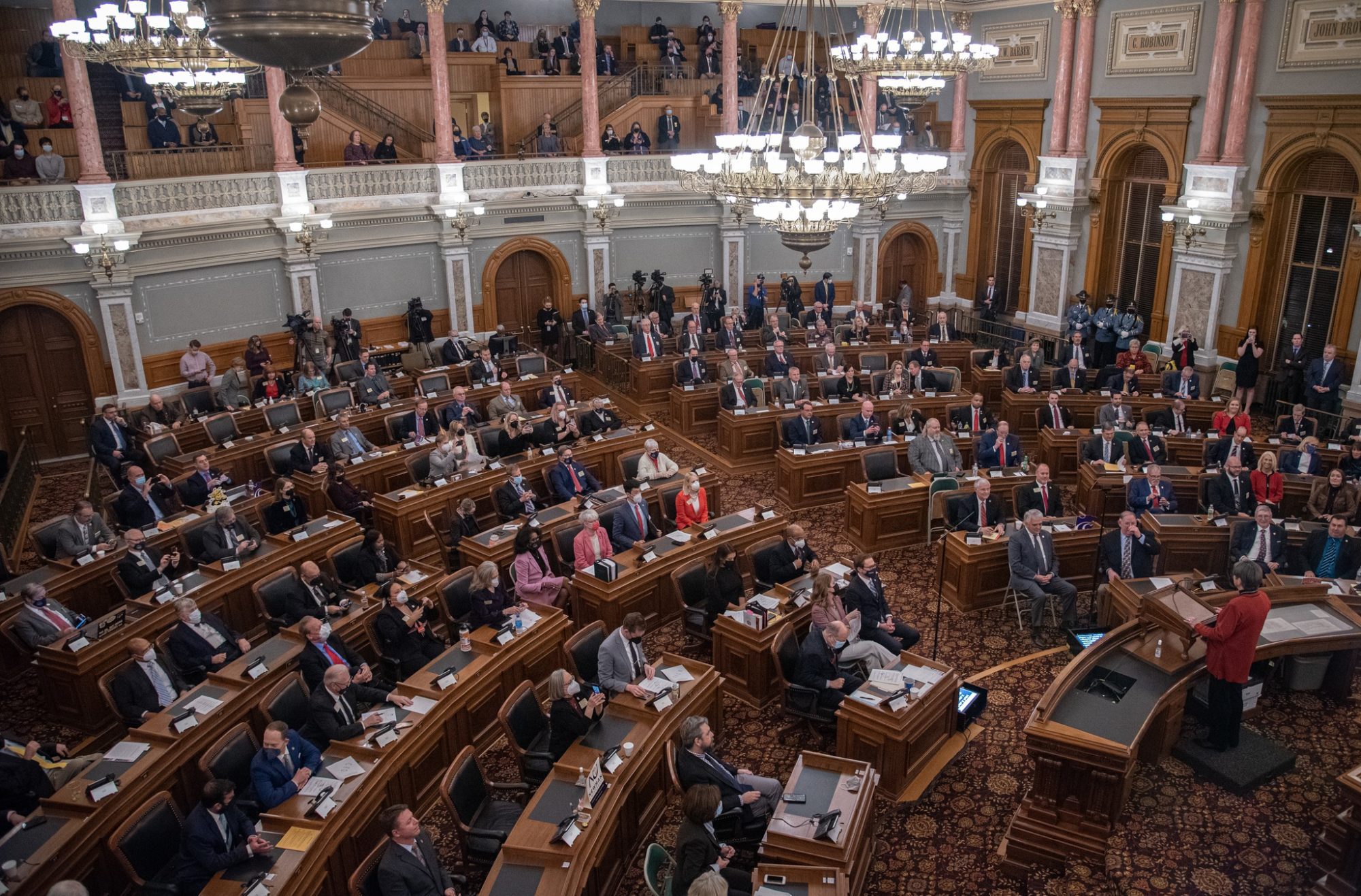

Members of South Carolina’s supreme court are elected by the legislature, which has a large Republican majority. But the legislature does not have absolute autonomy. The Judicial Merit Selection Commission considers prospective candidates and presents a slate of options to the legislature, which can elect one of the nominees or reject the entire slate and start the process over again.

Conservatives in red states have expressed frustration at such arrangements for preventing them from nominating politically reliable jurists on state courts. South Carolina’s process is built on informal but entrenched customs, which have historically included pledges of support for judicial candidates and vote-trading among legislators. The creation of the merit-based selection process in 1996 eroded some of these practices, but informal jockeying still takes place.

Still, for advocates in other states who are fighting similarly harsh abortion bans in the state courts, the outcome in South Carolina is encouraging and shows that even courts dominated by Republican appointees may be unwilling to sanction near-total bans on abortion.