Texas Students Are Again Battling the Closure of a Campus Polling Place

Local officials’ decision to eliminate early voting at one of the nation’s largest universities underscores the perennial fight to get or keep campus polling places in Texas.

Michael Barajas | September 15, 2022

This story was produced as part of the Democracy Day journalism collaborative, a nationwide effort to shine a light on the threats and opportunities facing American democracy on Sept. 15.

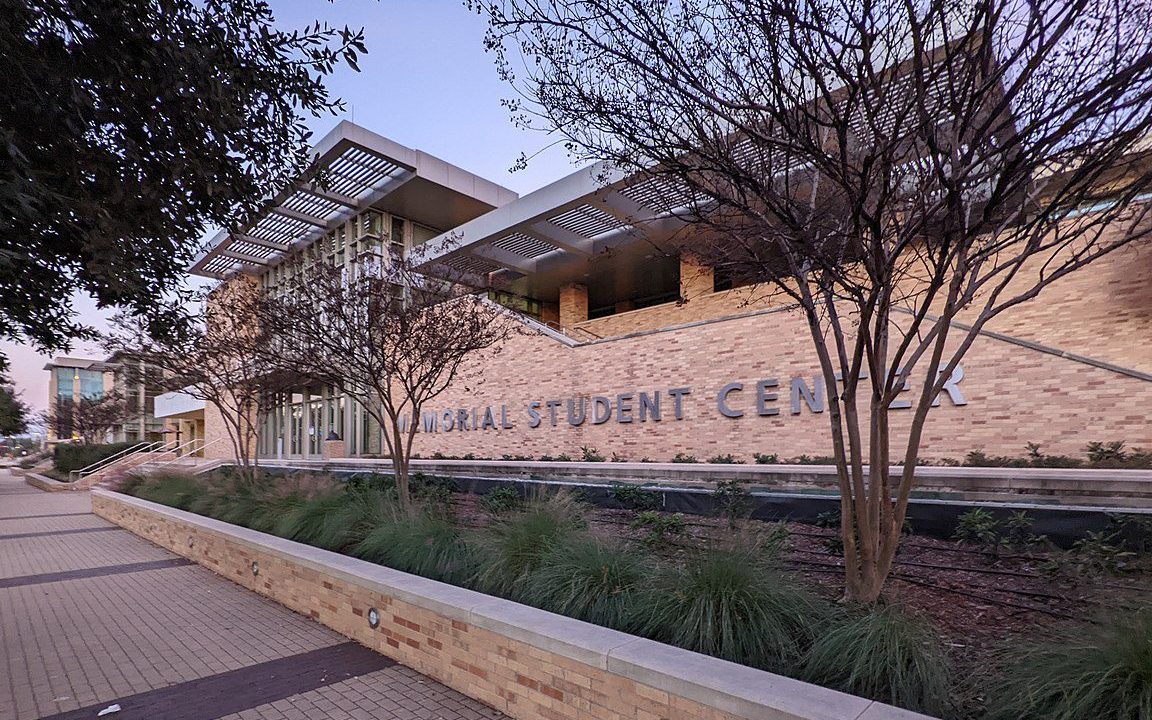

Like many young people, Kristina Samuel started voting during college. She was a freshman biology student at Texas A&M University during the 2020 primaries, casting her first ballot that year at the Memorial Student Center in the heart of the school’s sprawling 5,200 acre campus.

Samuel left what she thought was enough time to vote on Election Day, planning to visit the student center between her biology lecture that afternoon and a lab later that evening. But when she got there, the line to vote wrapped around the building, which was the only polling place on campus. Samuel, who says she waited about three hours to vote, recalls being the only person in her friend group who waited to cast a ballot in the election.

“I only stayed because I just knew how important it was, but I know so many people who are already on the fence about voting or who see it as a chore,” Samuel said. “They’re not going to wait in that three hour line.”

Samuel, president of her university chapter of the voting rights group MOVE Texas, and other student activists have asked for a second campus polling place to accommodate the largest student body in the state, and one of the largest in the nation. This summer, however, local officials took the opposite approach. The Brazos County Commissioners Court in July decided to eliminate the student center as a polling place during the two weeks of early voting for the 2022 midterms. Now there will be nowhere on campus for students to vote between Oct. 24 and Nov. 4.

“I’m afraid the reality is that we’re going to have such lower student and young person turnout than we normally would in a very crucial election,” Samuel told Bolts. The student center will remain an Election Day polling place this year, but Samuel worries that eliminating the early voting there will lead to longer lines that deter students who try to vote on Nov. 8.

Other TAMU students have denounced the majority-Republican commission for making this decision in early July, when most students were out of town for the summer. Ever since The Battalion, the university’s student newspaper, highlighted the exclusion in early August, they have asked officials to reinstate an early polling place on campus. The issue was not on the board’s agenda for its Aug. 30 meeting but several students attended to air their concerns. Sophomore Kevin Pierce stressed that the early polling place that officials picked instead for the precinct that includes the university—a new city hall building off campus—is about a half-hour walk each way for most students.

“The reality is that it’s going to be a lot harder to vote, and there’s going to be a lot of people who don’t vote,” Pierce said.

“The convenience of the MSC (student center) as a voting location cannot be overstated,” echoed Christopher Livaudais, a junior and president of Texas Aggie Democrats. County records show the center has been an early voting location since at least 2016. Another student, Varum Vuppaladadiyam told commissioners that losing all early voting on campus after asking for an additional polling place “feels like a slap in the face.” The commissioners took no action on that day. A later meeting where they agreed to discuss the issue was canceled this week when two commissioners didn’t show up.

The TAMU students join a perennial fight to get or keep polling places on large college campuses in Texas.

Students have fought for generations for equal voting access at Prairie View A&M University, the state’s oldest historically Black college and the second-oldest in the country. In 2018, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund sued on behalf of students when county commissioners refused to open a campus polling place for the same number of early voting days as in whiter areas of the county. The lawsuit followed decades of voter suppression against Prairie View students, including past attempts by officials to prosecute students for voting, as well as years of civil rights litigation and organizing over voting rights at the school; a federal judge decided against the students earlier this year, ruling that county commissioners had allocated early voting hours on an “objective and reasonable basis.”

In 2018, the Texas Civil Rights project had to threaten a similar lawsuit to secure access to early voting hours for students at another large public university in the state. Miguel Rivera, voting rights outreach coordinator with the group, says that eliminating or limiting polling places on college campuses compounds larger patterns of disenfranchisement in the state.

“These are all really big universities, and the demographics of our student population, our youth population, leans towards a population that is heavily people of color,” Rivera told Bolts. “This is just part of a long history in Texas of finding ways to disenfranchise specific segments of the population.”

Alex Birnel, advocacy director at MOVE Texas, says students in the state face numerous barriers to voting that can dissuade someone from casting their first ballot—from a voter ID law that accepts handgun licenses but not student IDs from public universities, to constantly shifting election laws and the cascade of polling place closures in the state over the past decade. Birnel also cited conservative attempts to stop schools from encouraging young people and staff to vote, and high schools across Texas that fail to follow a state law requiring them to offer at least two opportunities for all eligible students to vote every school year.

“In Texas, we apply the idea of rugged individualism to voting—that if you really wanted to, you’d jump over the hurdle, climb the mountain, cross the river, jump over the moat of alligators to cast your ballot, but then we pretend rhetorically that it’s like going to the grocery store,” Birnel told Bolts.

At the Brazos Commissioners Court meeting in July, one member dissented from the decision to remove the only polling site on campus. Russ Ford, a Republican, said his colleagues were “not really paying attention to what the people want and ask for,” adding, “we should be trying to get more people to vote, to make it easier to vote.” The four other commissioners, three Republicans and one Democrat, voted to approve the changes.

Nancy Berry, the Republican commissioner whose precinct includes the university, told Bolts that she recommended replacing TAMU’s early polling place with the city hall building after some of her nonstudent constituents approached her and asked for the change. She says they described campus as difficult to navigate for nonstudents.

“I had not heard from students, and I know all the students weren’t in, but we have a lot of students that come to summer school and they were in class and I didn’t hear from anybody,” Berry said, although county records show she was present at a July 2020 commission meeting when TAMU students delivered a presentation asking for more voting options on campus. “After we passed it, then I heard from students, and I’ve heard them loud and clear.”

Berry and other county officials insist it was too late to change polling places for this November’s election by the time students started speaking out in August, although Bruce Erratt, legal counsel for the county, told local media after the Aug. 30 commission meeting that adding early voting hours at the student center for this election was “legal but not practical.”

After ignoring the issue on Aug. 30, the commissioners added the future of the student center as a polling place to the agenda of their Sept. 13 meeting, and several TAMU students attended. But the meeting was canceled after two commissioners failed to show, in apparent protest of the county’s proposed tax rate, denying a quorum for the meeting.

Steve Aldrich, one of the commissioners who didn’t attend the meeting alongside Ford, told Bolts that the students protesting the change of early polling places should care more about property taxes, “because they end up paying them anyway…property taxes are also an issue for students.” Aldrich, a Republican, said he’s open to reconsidering the student center for an early polling place in future elections. But as for the possibility of two campus polling places, which was the goal for student organizers until commissioners slashed voting hours on campus this year, Aldrich suggested the cost of expanding campus polling places was too great.

“I know for a fact that, from a cost perspective, the cities at least are on record as saying we don’t want to have more than one early voting center per precinct,” he said.

Birnel says he hopes the debate over the polling place on campus ultimately sparks more organizing for greater investment in local elections infrastructure.

“You can imagine this other kind of system, where we spend resources for local elections departments to hire staff to scale up our ability to reach people,” Birnel said. “You can imagine a state that cared about voting and would fund that, you can imagine a situation in which those local elections departments crowdsource from organizations that do outreach every day and develop best practices in order to turn the tide on the status quo.”

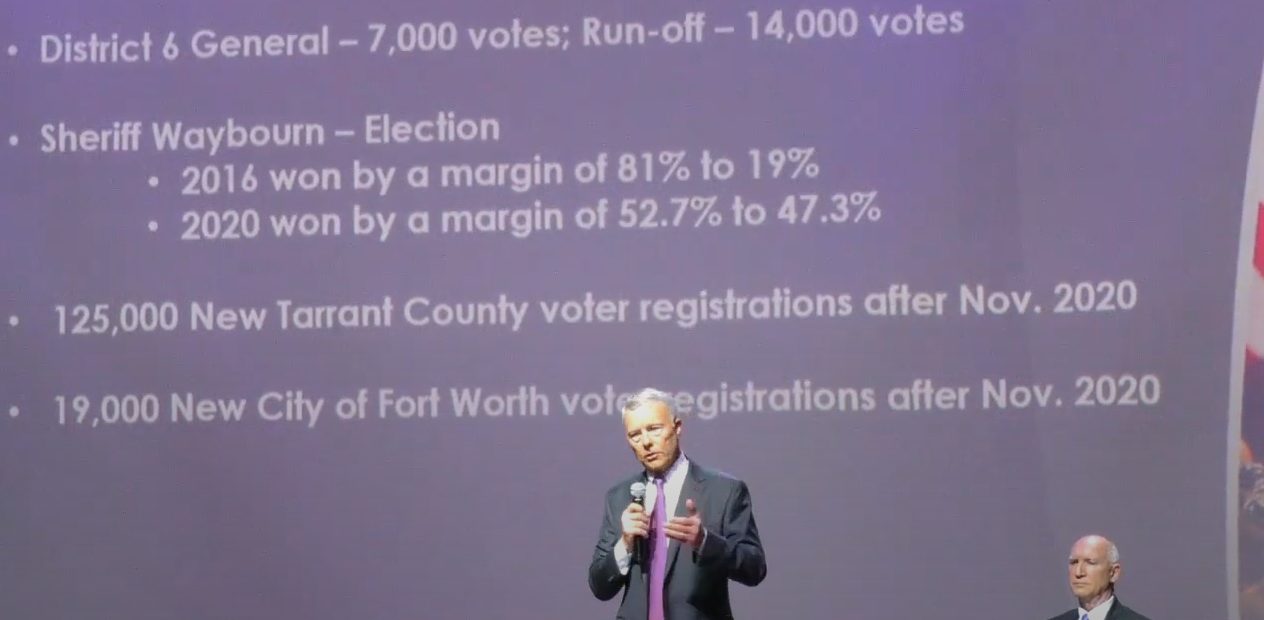

Birnel also pointed to climbing turnout among young voters in Texas in recent elections, which he calls “evidence of a Texas that’s changing.”

“Every cycle we see those numbers, and it seems like it’s just a matter of continuing to organize young people,” Birnel said. “But for us organizers on the ground in the state, it’s also a matter of preserving the places where students can vote.”

Sign up for our newsletter

Keep up weekly with the local politics of criminal justice and voting rights.