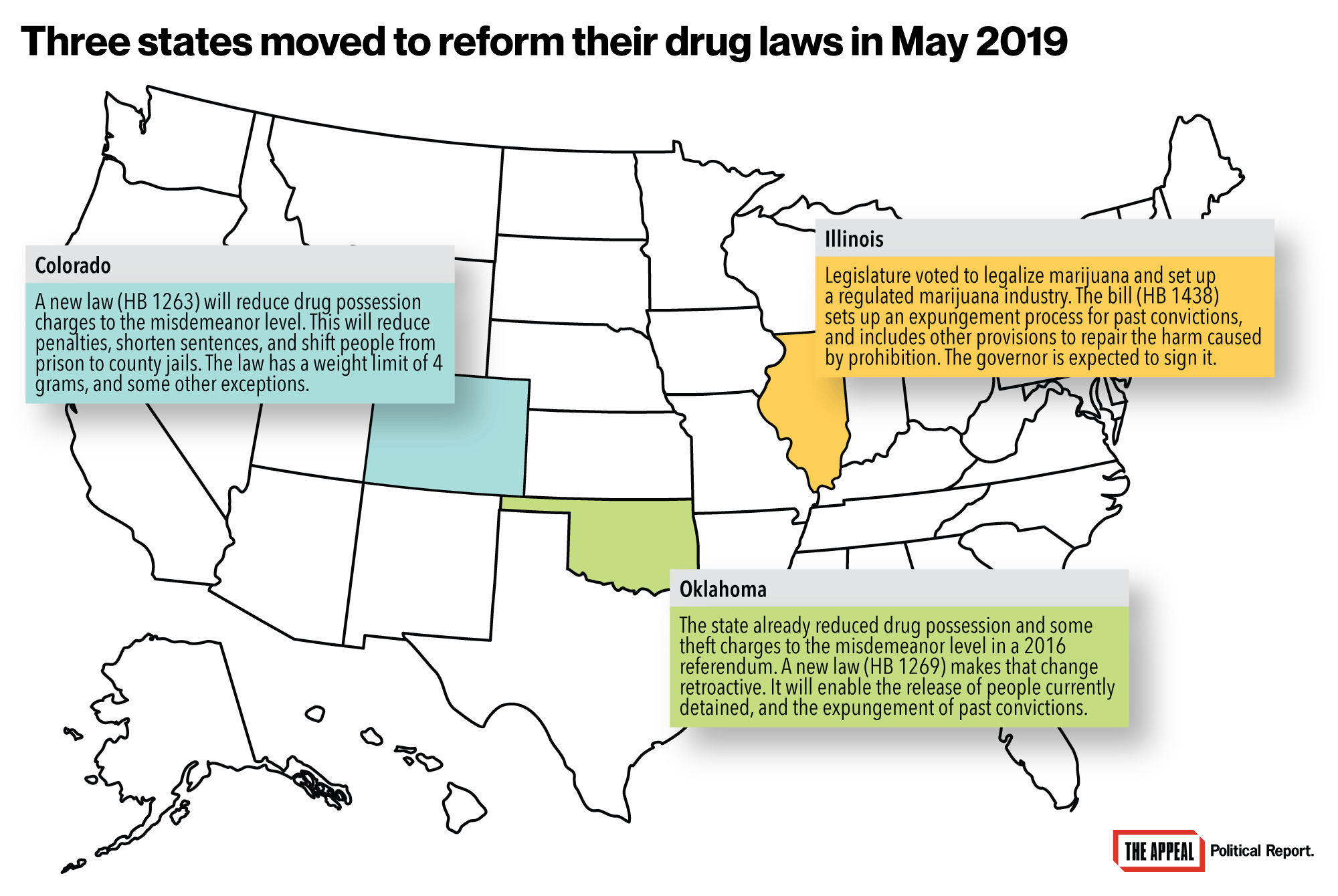

Legalized Pot, Reduced Sentences: Three States Reform Their Drug Laws

Illinois is set to legalize marijuana, while Colorado and Oklahoma tackled possession of other drugs.

Daniel Nichanian | June 6, 2019

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Pushback against the “war on drugs” has long been central to criminal justice reform efforts, and in May three states overhauled their drug laws to pursue less punitive models.

All three reforms will have a large impact, but all were also narrowed in the final stretch, often due to the opposition by prosecutors and their statewide associations.

Illinois legalized marijuana

Illinois is set to legalize the possession and sale of marijuana. The bill passed the legislature last week, and the state’s governor has said he will sign it. If he does, Illinois would become the first state to create a regulated marijuana industry via a legislative route (as opposed to via a ballot initiative), a testament to the issue’s shifting politics.

The bill faced a test beyond legalization: to confront the racially disproportionate harm that the prohibition of marijuana has caused. “We can’t move forward into the new world where marijuana will be legal and not take extra steps to repair that harm,” Roseanne Scotti, state director of the Drug Policy Alliance’s New Jersey office, told me in February. In legalizing pot, other states have often failed to clear past convictions, and the industry is primarily benefiting white investors. How does the Illinois legislation fare?

First, it sets up a streamlined pardon process to expunge existing convictions, which will relieve thousands from the lifelong implications of past prosecutions. Individuals will not need to initiate a request as long their offense involved less than 30 grams of marijuana. Relief will entail an individualized review process, however. The original legislation proposed a more automatic process, and it did not specify that 30-gram threshold, but it was amended after the state’s attorneys association demanded a greater role for prosecutors in determining eligibility.

Second, the bill allocates some of the revenue generated by legalization to programs meant to reverse the “systematic disinvestment of the same communities where folks with criminal records are concentrated,” as Sharone Mitchell Jr., deputy director of the Illinois Justice Project, put it. The legislature “did extremely well when it comes to the equitable distribution of cannabis tax proceeds,” Mitchell told me. “The 25 percent share of the tax revenue reserved for violence prevention, re-entry services and social determinants of health” are a “game changer when it comes to violence reduction.” Mitchell credited the work of the Illinois Black Caucus.

Third, it boosts the licensing applications submitted by residents of “disproportionately affected neighborhood” and of people with past convictions. Fourth, it provides financial assistance for people who want to enter the marijuana industry and who have been directly impacted by its prohibition; nevertheless, opening a dispensary will still entail a very high startup cost. Mitchell said that “Illinois has clearly done better than other states” when it comes to “minority inclusion in the industry,” but that “it is not the perfect bill when it comes to inclusion” because “industry giants that may not feature racial diversity still have the potential to dominate the industry.

Kim Foxx, the chief prosecutor of Cook County (Chicago), testified in favor of legalization and of those equity provisions. Earlier this year, Foxx earlier launched a process to facilitate the expungement of past marijuana convictions in Cook County.

Earlier this year, New Mexico and North Dakota reduced the prospect of facing incarceration for possessing pot. Promising reforms derailed in other states, including New Jersey and Texas.

Colorado reclassifies drug possession charges, and shrinks penalties

Colorado is lowering drug possession to the misdemeanor level. This new law, effective in 2020, reclassifies possession of nearly all Schedule I and Schedule II substances, including heroin and fentanyl.

This significantly reduces penalties associated with possessing these drugs. It shortens sentences and shifts people from prison to county jails. Drug possession currently carries a prison sentence and a subsequent parole period, but this change provides a sentence of up to 180 days in jail and a probation period.

The Senate limited the original bill’s scope, however, when it added a weight limit of 4 grams over which possession remains a felony. The law also contains other exceptions. It never applies to cathinones, flunitrazepam, ketamine, gamma hydroxybutyrate (GHB). Possession of other substances will also be a felony beyond a third offense. In addition, the law will not apply retroactively.

Five states have reclassified drug possession into a misdemeanor, all since 2014, according to a 2018 report published by the Urban Institute: They are California, Connecticut, Oklahoma, Utah, as well as Alaska (which may soon roll back its reform). The report finds that none of these states specify a weight limit; some do raise charges to a felony after repeated convictions.

Brian Elderbroom, a scholar at the Urban Institute who co-wrote the 2018 report with Julia Durnan, called Colorado’s bill a “critical first step.” He added, though, that it does not meet the standard of the five reforms assessed in his report. It “builds on reclassification efforts in other states by also limiting incarceration in local jails and investing in treatment programs,” he told me, but “lawmakers left plenty on the table when they amended the bill to retain the felony classification in certain cases.” He added that “incarceration should never be the response to addiction or substance abuse,” which “should be a public health issue.”

Oklahoma had already ‘defelonized’ drug possession. Now that became retroactive.

Drug possession is already a misdemeanor in Oklahoma. Voters reclassified it in a 2016 ballot initiative, State Question 780, that passed by a large margin; it also reclassified theft of under $1,000. But SQ 780 was not retroactive; people already convicted got no relief.

This just changed. House Bill 1269, signed into law in May, makes SQ 780 retroactive. It instructs the state to identify and resentence people now in prison for felony drug possession. (People convicted of other offenses in addition to drug possession, and people convicted of theft, will need to file a commutation petition to be considered.) Up to 800 people who are serving simple possession charges will be eligible for release, The Oklahoman reports.

The law also makes already-released individuals eligible for expungement. Up to 60,000 people could qualify for this form of relief, according to Kris Steele, the executive director of Oklahomans for Criminal Justice Reform, a coalition that supported the change. Steele is also the state’s former Republican speaker. “When an individual can remove that scarlet letter, it opens up a myriad employment opportunities and new housing opportunities, it allows that individual to move forward in a very positive manner,” Steele told me.

But Steele also expressed concerns about the way lawmakers set up the expungement system. For one, the reform requires individuals who are eligible to file an application rather than shift that burden on the state. Steele said that although the reform provides a simplified application, people may still perceive the process as too burdensome. “Many individuals who are involved in the justice system may be skeptical of applying because it is additional involvement with a system that has been punitive,” he said.

Other “caveats” include the stipulation that people with past felony convictions must complete all treatment criteria and pay full restitution before obtaining an expungement. People arrested today face no such preconditions to be charged with only a misdemeanor, and Steele argued that “true retroactivity” should mean that people convicted before SQ 780 became effective are “treated exactly the same.” He said of the requirement to pay restitution before obtaining an expungement that “what we don’t want is to create a disparity between individuals who have resources and individuals who may be living in poverty.”

Oklahoma is only the second state, along California, to reclassify drug possession retroactively.

Yet HB 1269 is the only major criminal justice reform that Oklahoma, which has the country’s highest incarceration rate, will adopt this year. Legislation to reduce the use of cash bail, waive some fines and fees, and lessen sentencing for some nonviolent offenses had some early success, but the legislature adjourned without adopting them. Steele said that this is “primarily because of the opposition of district attorneys.” Prosecutors “are very effective within the state legislature in thwarting reforms that would reduce incarceration, and they work with other law enforcement entities such as the sheriff associations to defend and protect the status quo,” he added.

The Oklahoma District Attorneys Council, the association that lobbies on behalf of prosecutors, had also raised concerns about HB 1269 and retroactivity. NPR reports that the bail bond lobby also contributed to derail these reforms.