“They Force You to Work”

State and local governments are racking up profits and savings through unpaid labor in prisons, a new report documents.

| June 17, 2022

As Houston officials prepped their annual budget two years ago, a staffer for city council member Abbie Kamin was taken aback while examining a contract the city was on the verge of approving. The Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ) had submitted a $4.2 million bid for a contract to repair tire treading on city trucks, a price some $750,000 below the competing bid. Kamin says her staffer broke down just how exactly TDCJ could float such a low price: with unpaid labor from incarcerated people forced to work inside a prison that also happened to be named after a slaveholder.

Kamin, who was then in her first year in office, was alarmed enough to pull in another freshman council member, Carolyn Evans-Shabazz. The two met with TDCJ representatives to learn more about work programs inside Texas’ sprawling prison system before deciding on the contract. Kamin says the conversation inflamed rather than eased their concerns. She was appalled after realizing that Texas prisoners can face harsh punishment for refusing work assignments and that, along with being unpaid, many of them live and labor inside facilities without air conditioning in a state that regularly experiences triple-digit heat.

After their meeting, the council members quietly convinced Houston Mayor Sylvester Turner to post a new request for bids for tire retreading, this time with added language requiring worker compensation in line with industry standards. The state’s prison system didn’t even reapply and the contract went to a private company, albeit at a higher price.

“We were not comfortable with these practices,” Kamin told Bolts. “Bottom line, the conditions are awful, the practice is terrible, and we’re one of only a handful of states left that even continue this practice. It’s just flat out wrong.”

Texas is one of seven states, all in the South, that force people in prison to work but pay them nothing for almost all jobs. (The others are Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Mississippi, and South Carolina.) Most other states only pay out pennies compared to what that labor would cost on the outside, according to a report published this week by the Global Human Rights Clinic at the University of Chicago Law School and the American Civil Liberties Union that catalogs prison work practices and profits across the country.

The report estimates that around 800,000 people confined to U.S. prisons perform labor during incarceration, and that most say they are forced to work or else face additional punishment, such as solitary confinement or loss of family visits. Citing prison records, court documents and surveys with incarcerated workers, the report found that even prisoners who receive some pay for their work still mostly cannot afford basic necessities like soap thanks to exorbitant commissary prices and court costs, restitution and even “room and board” fees that garnish their meager wages.

Jennifer Turner, a human rights researcher for the ACLU and lead author of the new report, says that incarcerated labor is inherently exploitative and dangerous, with people not only forced and coerced into prison jobs but also largely excluded from workplace safety protections.

“Most of this labor is happening in a sort of black box where there’s no outside oversight, and basic protections for safety and training simply don’t apply,” Turner told Bolts, pointing to instances of people maimed or killed on the job—incarcerated workers in North Carolina who received only diaper rash cream after suffering chemical burns, a kitchen worker in a Georgia prison who had his leg amputated due to improper medical care for a wound he suffered from slipping and falling at work, a prison sawmill operator in Colorado who was nearly decapitated after a supervisor ordered her to dislodge a piece of wood blocking a conveyor belt. According to written surveys that Turner and other researchers conducted for the report, most prisoners cite hazardous job conditions and little to no formal training, even when tasked with work involving heavy machinery.

“People are not given personal protective equipment and other types of standard safety equipment, like machine-guarding mechanisms when you’re dealing with sharp objects,” Turner said. “It’s very different from workplaces outside of prisons, because on the outside, people supervising you usually have some experience, they’re more likely to give proper job training on dangerous equipment or have some kind of oversight. That’s just not the case in prison.”

The beneficiaries of all this coerced and dangerous labor are primarily state governments. Prisons are propped up by incarcerated people forced to help operate and maintain their own systems of confinement—the most common prison jobs, according to Turner’s report, range from laundry and grounds maintenance to kitchen and building repairs.

And as the Houston example indicates, prison systems also rake in profits by monetizing the products and work produced by the people they detain.

Texas Corrections Industries (TCI), a division of the state prison agency, sold nearly $77 million prisoner-made goods and services in 2019 to a broad range of government agencies as well as “public schools, public and private institutions of higher education, public hospitals and political subdivisions.” According to the new report, commodities and services sold outside prisons make up a significant share of prison labor and have risen in tandem with mass incarceration, from around $650 million in sales in the early 20th century to more than $2 billion in 2021.

And other government agencies can and often do benefit from this captive labor pool to secure far cheaper contracts than they otherwise could. Data obtained from TCI show an array of municipalities, counties, local school districts, universities and medical systems across the state buying everything from cheap chairs and desks and other office equipment to aprons, lab coats, and even ornamental plaques for awards produced with forced and unpaid prison labor.

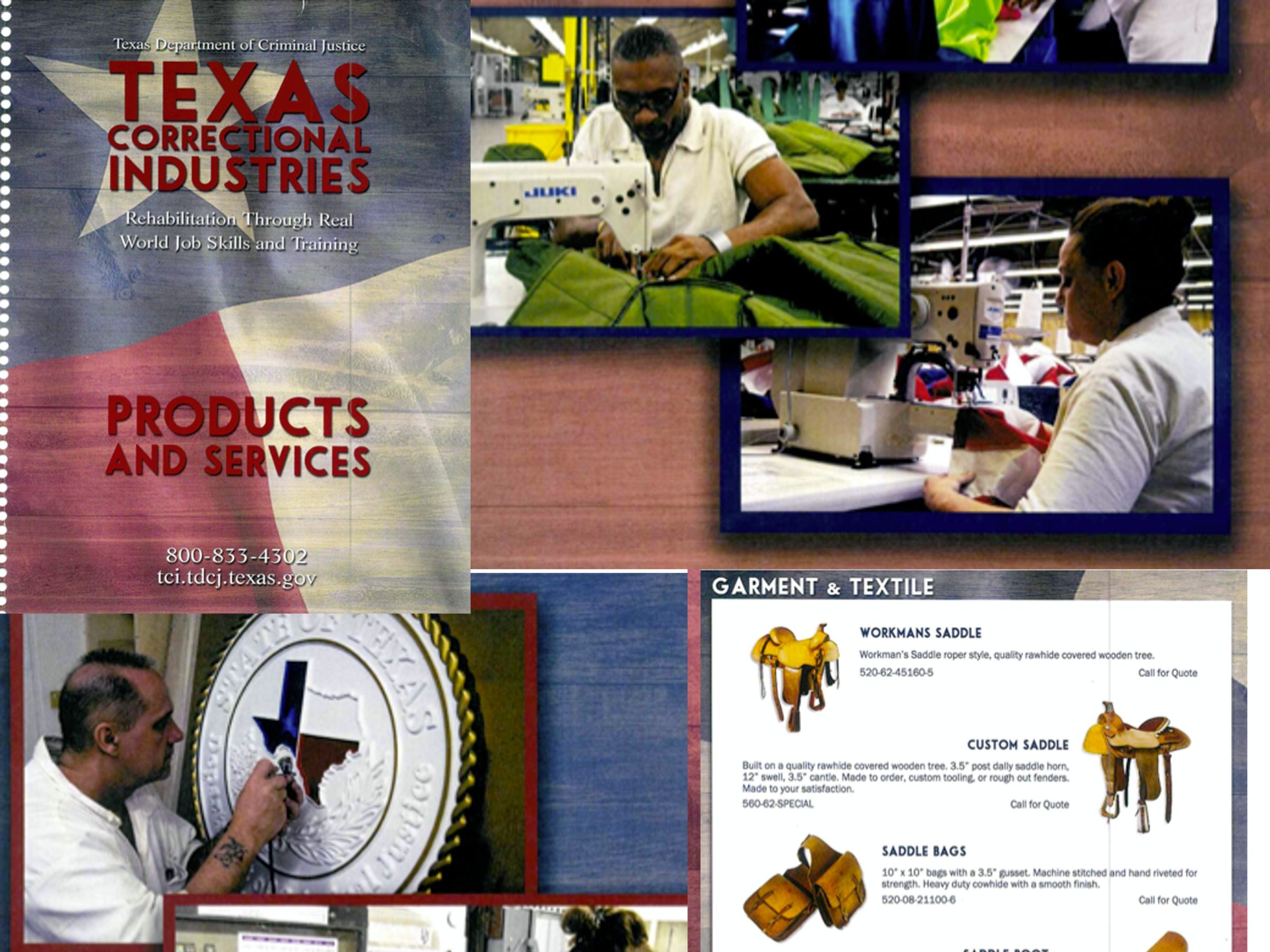

TCI also publishes the prison iteration of an IKEA catalog to advertise its goods and services, and it operates showrooms in south Austin and Huntsville, about an hour’s drive north of Houston where the state prison system is headquartered. Lawmakers in Texas, who are permitted to benefit from low-cost prison-made goods, have in the past purchased furniture and other trinkets adorned with the state seal and flag to adorn their homes or gift to top campaign donors.

“What really made an impression was to see how just the vast majority of work performed by people who are incarcerated is for the benefit of the prisons and state and local governments,” Turner said. “I think sometimes there’s a real misunderstanding that it’s largely for the benefit of private corporations.”

Prison agencies justify their reliance on forced and unpaid, or underpaid, labor by claiming they’re providing benefits beyond money, like keeping people busy in lockup or teaching them job skills to help them succeed after release. The cover of TCI’s products and services catalog declares, “Rehabilitation through real world job skills and training.” TDCJ responded to the recent report and claims that unpaid prison labor is inherently exploitative with a statement saying, “While inmates are not paid, they can acquire marketable job skills which could lead to meaningful employment upon their release.” However most incarcerated people, formerly incarcerated workers, and advocates for people in prison vehemently dispute such claims.

“They force you to work, you’re guaranteed to have a shitty job and it’s guaranteed to be work that is tortuous,” David Johnson, an activist and organizer in Texas who did time in the state’s prisons, including stints where he was forced to work on a prison farm, told Bolts. “You are guaranteed to have a job that comes with no privileges and all downside, you are forced to work in the fields in the sweltering heat and deep cold. …It is tortuous, physically and emotionally and psychologically.”

Low to non-existent wages for imprisoned workers also mean that their loved ones on the outside, who may already be struggling because of their incarceration and loss of earnings, must bear the full weight of supporting their survival in prison. The families of incarcerated people shell out billions every year on exorbitant commissary costs and phone calls, often forced into debt just to keep in contact with a family member or help them with basic necessities not provided by the prison system.

“Incarceration puts an incredible monetary strain on family members,” said Savannah Eldrige, who has family inside Texas prisons and advocates for better conditions and treatment for incarcerated people. “The experience of supporting a loved one behind bars can be financially overwhelming because of all the expenses they have inside, from hygiene to health care, and the fact that they are no longer wage earners—I mean, where’s the money gonna come from? It’s gonna come from family.”

Eldridge and Johnson are part of a growing national movement that seeks to abolish forced labor and servitude behind bars. They stress that much of the country’s modern prison archipeligo evolved from slavery, with convict-leasing and prison farms and laws that criminalized newly emancipated people replacing slave plantations after the Civil War. Johnson, who is Black, says he often thought of that history when he was forced to work the fields while incarcerated.

“It was always clear that there was a parallel between working in those fields and slavery,” Johnson said. “We had open conversations out there about how those conditions, how those armed men on horses guarding us evoked that history.”

Johnson and Elridge are part of Abolish Slavery National Network, a coalition pushing for state and federal legislation to close a loophole in the U.S. Constitution’s 13th Amendment, which was passed during Reconstruction and banned slavery and involuntary servitude except as punishment for a crime.

Advocates in many states are pushing for anti-slavery language in their state constitutions. Voters in Nebraska, Utah and Colorado have all passed anti-slavery amendments in recent years, and similar measures will go to voters this year in Alabama, Louisiana, Oregon, Tennessee, and Vermont. According to the coalition, there are also active efforts in Florida and South Carolina. Citing the new ban on involuntary servitude, people incarcerated in Colorado have sued the state seeking better wages and treatment and alleging the state is ignoring the will of voters by continuing to coerce prison work under the threat of punishment.

Texas lawmakers have largely ignored the issue, in keeping with how they’ve ignored other crises inside state lockups. But discussions of prisoner pay and forced labor have started to circulate inside the state capitol. The state House held a hearing in 2019 on a bill to pay people incarcerated in Texas prisons $1 a day for their work. “The penal system today is slavery,” Alma Allen, a state representative from Houston, said during the hearing. “It is a legal way to enslave people.” The committee never voted on the bill. Legislative proposals to pay incarcerated people somewhat higher wages has stalled in other states like New York, too.

Even with the lack of movement on the state level in Texas, Kamin, the Houston council member, says that local government officials have a role to play in ending exploitative prison labor. She says the awareness of a city staffer and their willingness to research what looked like a routine contract for truck repairs became a wakeup call about local government’s role in a system that many equate to modern day slave labor. “This could have totally flown under the radar,” Kamin told Bolts.

Kamin says her office got a flood of messages from incarcerated people after Houston turned away from TDCJ’s bid. “I cannot tell you the number of letters that I received from inmates thanking us for the stand we took,” she said. “So many people reached out to say how they feel about the work programs in prison and how bad they are. It was mostly just a plea for help.”