Under Glenn Youngkin, Parole in Virginia Has Nearly Vanished

“What’s the point of having a second chance available when you’re not willing to give it?”

| May 20, 2024

This article is produced as a collaboration between Bolts and Mother Jones.

In early April, Sarah Moore got the news she was dreading: Her husband, Dennis Jackson Moore, had been denied parole again. It was his fourth rejection in as many years.

Dennis, who goes by Vega, is 45. He has spent more than half his life in prison in Virginia for a murder and armed robbery he committed as a teenager. At the time, his defense argued that he did not fully understand the charges against him and had been misled by a detective when he gave a recorded confession. Vega was tried in adult court. Prosecutors called him a “cunning seventeen and three-quarters-year-old who committed a violent and senseless act.” When Vega was 18, the jury found him guilty and a judge sentenced him to 53 years in prison.

Up until four years ago, Vega, like most people in Virginia prisons, was not eligible for parole. But in 2020 state lawmakers extended the possibility of early release to Vega and hundreds of others who carried out crimes as juveniles and have served at least 20 years of their sentence. “We are a nation of second chances,” Senator David W. Marsden, a Democrat who sponsored the Senate version of the bill, said at the time, “and those who are incarcerated for long periods of time when they are juveniles are especially deserving of that look.”

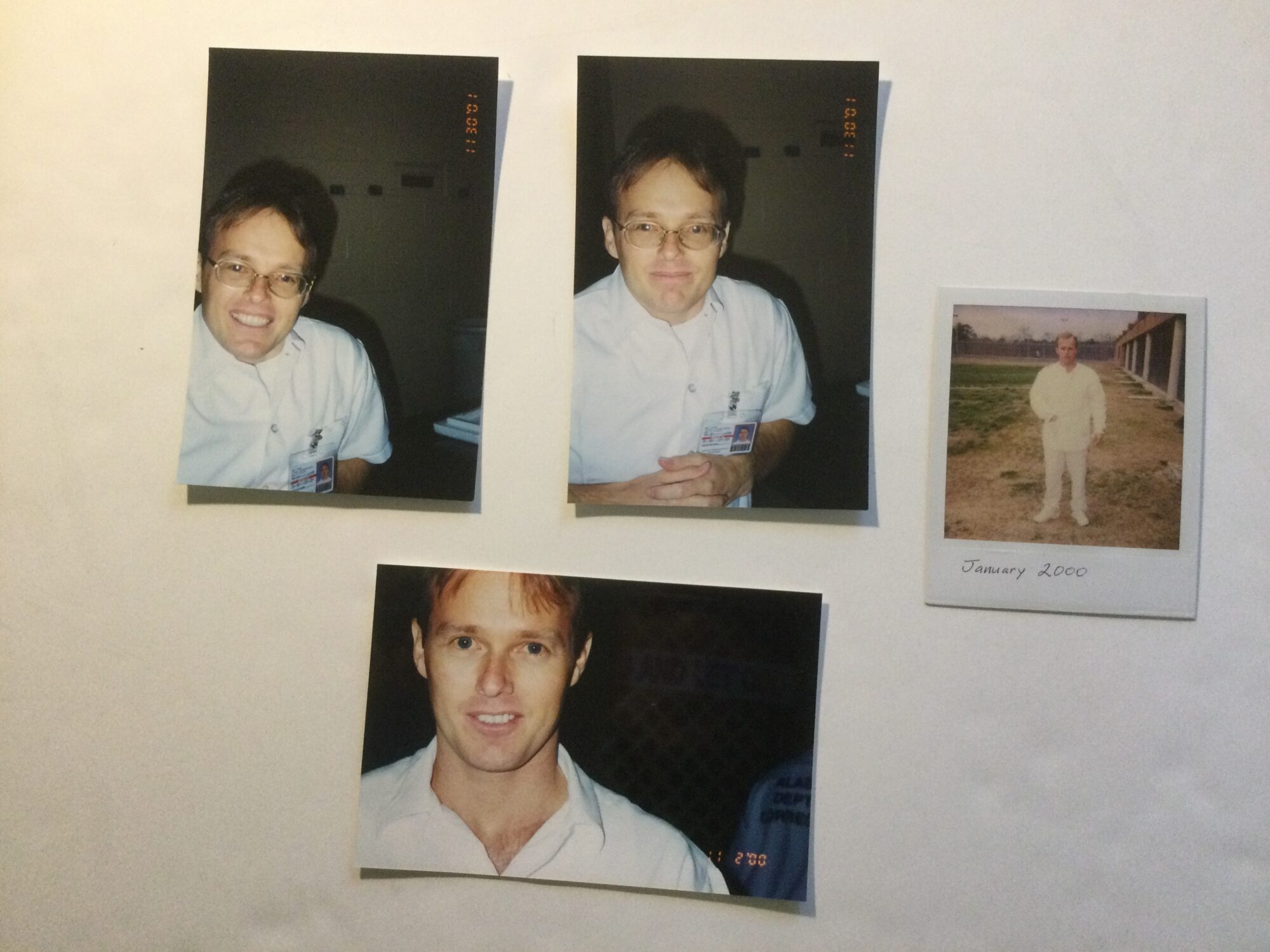

Vega’s 38-page application packet to the parole board makes the case that he is no longer a “misguided seventeen-year-old who made extremely reckless and thoughtless decisions.” He says he has spent more than two decades behind bars working to better himself—getting his GED, teaching himself multiple languages, studying real estate, marrying Sarah, and learning to care for her two daughters and son from afar. Vega says he’s become a rehabilitated and remorseful man worthy of an opportunity to rejoin society. If he ever gets out, he wants to help at-risk youth avoid incarceration. “I’ve grown up in prison,” he writes, “but I will not make prison my life.”

After repeated denials from the parole board, Sarah says any second chance for her husband only seems good on paper. Like in previous decisions, the parole board’s most recent denial delivered in late March stated that releasing Vega would diminish the seriousness of his crime and he should serve more time. “We’re just so frustrated,” Sarah said after his latest rejection. She’s left wondering: “What more does he have to do?”

For Vega and others eligible for parole in Virginia, the odds of being released have gone from slim to nearly impossible in recent years under new GOP leadership, according to Mother Jones’ and Bolts’ analysis of monthly parole board decisions.

Under past Democratic administrations, Virginia already had one of the harshest parole systems in the nation, with single-digit annual approval rates. But parole grants have declined even further since Republican Governor Glenn Youngkin began to overhaul the parole board in 2022, dipping to an approval rate of just 1.6 percent in 2023. So far this year, Youngkin’s parole board has approved only eight of the 628 applications it considered, a grant rate of 1.3 percent, according to Mother Jones’ and Bolts’ analysis.

In March, the month Vega was denied for a fourth time, the board approved only 2 out of the 117 cases it considered.

As chances for parole decline across the country, experts say the Commonwealth stands out. “Virginia is paroling basically nobody,” says Wanda Bertram with the Prison Policy Initiative. The blanket denial of conditional release to deserving candidates, supporters of parole argue, ultimately advances blind punishment and undermines incentives toward rehabilitation and positive change.

Vega says he now understands the devastation caused by his actions. “I took a life and I don’t condone that,” he says. “I don’t even understand my thoughts at that time, but I feel for the victim’s family.” (In a 1997 victim impact statement, the mother of Vance Horne, the man he killed, wrote that the loss of her son felt “as though a part of my body, a part of my very being has been taken away without warning or reason.”) In the years since, Vega says he’s become a different person. “I’m not the same guy anymore,” he explains. “Who of us is the same person they were at that age?”

He also sees how the crime hurt his own family; Darlene Smith, Vega’s mother, says his arrest for the murder felt like “someone reached in my chest and pulled my heart out and just set it on fire.”

With every “no” from the parole board, Vega and his supporters feel like the system is dangling a possibility for release that will never materialize: “What’s the point of having a second chance available,” he wonders, “when you’re not willing to give it?”

Almost two decades ago, during the height of a nationwide wave of tough-on-crime policies, Virginia effectively abolished parole by adopting a “truth-in-sentencing” law. The new rules mandated people serve at least 85 percent of their sentences. Only elderly prisoners, or those convicted before the law was enacted in 1995, were eligible for parole.

Before parole was gutted, 46 percent of eligible candidates in Virginia were granted early release. By 1998, that figure had dropped to 5 percent. Although the number of people up for parole has grown in recent years as a result of criminal justice reforms expanding eligibility and an aging adult population, their chances of actually getting out have remained low. Only about 6 percent of parole applicants were approved under Terry McAuliffe, the state’s Democratic governor from 2014 to 2018.

Recognizing a problem, McAuliffe created a state commission to study reinstating parole, questioning whether Virginia kept too many people in prison for too long. In 2019, Democrats seized control of the rest of the state government. Soon after, Virginia extended parole eligibility to juvenile offenders like Vega, as well as to people convicted by juries between 1995 and 2000 because of constitutional issues with how trials were conducted at the time.

But even with those expansions, parole releases were still a drop in the bucket compared to a state prison population of roughly 24,000. This contributed to Virginia’s crowded prisons and aging incarcerated population—at a high cost to taxpayers.

“The expectation pre-1995 was that you had a very good chance of receiving parole once you were eligible to be reviewed,” says Allison Weiss, a professor of prison litigation at Washington and Lee University School of Law who teaches a course where students assist parole applicants. “Over time, there’s just been a narrowing of the view of what parole is or should be in the state.”

By the time McAuliffe ran for governor again in 2021, Youngkin had folded attacks on Virginia’s already-restrictive parole system into a broader GOP campaign that painted Democrats as soft on crime. “Terry McAuliffe’s hand-picked parole board had one mission—cut them loose,” Youngkin posted on X during the race, adding that Virginia wouldn’t be safe under his opponent.

After taking office the following year, Youngkin swiftly fired his predecessor Ralph Northam’s five-member parole board and installed his own appointees, some of whom had openly opposed releasing people on parole—triggering a political standoff with Democrats who still control the state Senate and must confirm the governor’s nominees. The Senate blocked most of Youngkin’s initial selections, except for Chadwick Dotson, a former judge and prosecutor who was chosen to chair the parole board.

Even before this battle to reshape it, the agency was already in disarray. In 2010, prisoners who were eligible for parole but denied multiple times sued the parole board, claiming it refused to properly consider their cases; the reason for denial provided in most instances was the seriousness of the original crime. A 2021 report from Washington and Lee University found deficiencies in the board’s decision-making process, including the fact that members don’t meet in person to discuss cases and instead vote electronically.

Virginia Republicans have also criticized the parole board for failing to give legally required notices to victims and prosecutors when considering releases and for proceeding with some releases without receiving recommendations from local parole officers. As chair, Dotson issued a report to the governor last year calling for “drastic changes” to the board, like opening the hearings to the public and expanding the number of board members.

Under Youngkin, the board has consistently been missing a fifth member, working at times with as few as three members, which experts say further diminishes chances for parole applicants.

Several advocates for people seeking parole say Dotson seemed to make improvements to the board’s practices. During his tenure, Dotson made visits to parole candidates, sometimes accompanied by other board members. Members also began gathering on a weekly basis to debate cases where there was “reasonable chance” of granting release.

“I think he did give people a fair chance,” says Lisa Spees, who has advocated on behalf of more than 30 parole candidates in Virginia over the years. “He implemented a lot of changes into the parole system that were much needed.” Having the opportunity to meet with a parole board member, Spees added, “gave the individual a sense of being a part of that decision-making process.” She and others fear that Dotson’s departure last year brought that momentum to a halt.

Even with those improvements, when Dotson chaired the board, between January 2022 and September 2023, the grant rate was only about 2 percent.

Last September, Youngkin replaced Dotson as board chair by appointing Patricia West. A one-time judge and former chief deputy attorney general, West also once acted as state director of juvenile justice; decades ago she served on Republican Governor George Allen’s commission that pushed for minors as young as 14 to be automatically tried in adult court when charged with some violent offenses.

Shawn Weneta, who was until recently a policy strategist with the ACLU of Virginia, calls West “the architect of parole abolition in Virginia.” He points to her role during the Allen administration, which led the charge to eliminate parole. In 1996, Allen picked West as secretary of public safety overseeing Virginia’s prisons and parole. “We have serious concerns with her being in that role [of parole board chair],” Weneta says.

At first, Senate Democrats tried to remove West from a list of gubernatorial appointments pending confirmation. But, with little explanation, they voted a few days later to confirm her. Between her appointment last September and late March, West has voted on fewer than 50 cases to consider parole, according to state records showing individual board members’ voting history. She approved just three people for release, all of whom were eligible under geriatric release—available for applicants 65 or older after serving at least five years of their sentence and those 60 or more who served a minimum of 10 years.

Julie McConnell, a law professor at the University of Richmond and director of a defense clinic that works on juvenile parole law cases, says Virginia’s current parole board only seems to be approving such geriatric cases. In past years, McConnell says her legal clinic won parole for seven candidates who committed crimes as juveniles.

So far in 2024, she says none of the applicants represented by her clinic have been granted parole.

“I don’t know that there is a silver bullet with this board where you can present the perfect package to them that gets their attention,” McConnell says. She suspects the board focuses more on aspects outside of the applicant’s control like the crime itself or input from the prosecutor and victim’s families.

“The Parole Board deals with some of the most heinous and violent offenders within the Department of Corrections who are eligible for parole,” Youngkin’s press secretary Christian Martinez said in an email. “Judge West and the Parole Board assess each case with a comprehensive approach, guided by policies that prioritize the voices of victims before any decision is made to release violent offenders back on the street. Parole is not a right, it’s a privilege extended only to those inmates who are eligible for consideration.” West declined to answer questions for this story.

Advocates for people seeking parole now worry that a recently announced policy change will even further decrease their chances of release. Starting in July, victims of people applying for parole will still be entitled to annual appointments with the board, while meetings with families and advocates for the parole applicants will instead now happen every two years.

“We’ve just become so acculturated to extreme punishment that we don’t even recognize when we’re going too far,” McConnell says. “We could give people an opportunity for a fresh start.”

In late February, Leroy Gilliam III became one of the lucky few to be granted parole in Virginia.

Gilliam, 51, had already served almost 28 years for first-degree murder by the time he went before the parole board last June. The board had denied him twice in recent years due to the serious nature of his crime. But this time, the board decided Gilliam had shown “excellent institutional adjustment” and didn’t present a threat to public safety.

Gilliam was both thrilled and perplexed by the decision: “I don’t know what actually changed their minds this time.”

Parole board decisions could soon at least become less opaque in Virginia. Last year, Youngkin signed a bipartisan transparency bill into law that the ACLU touted as “the biggest reform of Virginia’s parole system since 1994.” Under the new law, which takes effect in July, the board will have to publish more regular detailed reports with individualized reasons on grants and denials, and parole review hearings will be required to include interviews with candidates themselves. The bill also gives parole applicants and their attorneys access to all of the information being considered by the board.

“We don’t know that it will increase grant rates at all,” Weneta says. “We certainly hope that it helps. But it’s a piece of the puzzle.” He believes insulating the parole board from the influence of any individual politician is the only way to ensure an equitable system. “As long as we continue to have partisan actors setting the mandate and making the appointments, they’re going to achieve the outcomes that they want,” he says, adding that the ultimate goal is to reinstate parole for everyone.

When Vega’s stepdaughter, Shaelyce, first spoke to Virginia’s parole board two years ago, she told them how he had become the first male role model in her life. Before Vega came into the picture, Shaelyce says her mother had been in a 13-year-long abusive relationship and they were living out of a hotel. Shaelyce, 22, is now studying to become a child psychologist to work with children who have experienced trauma.

Shaelyce remembers pouring her heart out to the board, but says it didn’t seem to make a difference. “It’s like there’s a tablecloth that we place on the table,” she recalls with tears in her eyes, “and every time we get ready for him to come home, they sweep it right from underneath us.” Her sister Carol, 24, has also come to see Moore as a father figure. “We got all these plans,” she says. “We talk about what it’s going to be like and then to get denied it’s heartbreaking.”

Darlene Smith, Vega’s mother, says she goes through bouts of depression and shuts down after each denial from the parole board. “He picks me up and he tells me, ‘Mom, I didn’t have this chance when I first went to prison,’” she says. “‘At least now I have a chance.’” But in Virginia, that chance is increasingly unlikely.

Sarah says each denial feels personal, like the support she and her family have given him is insufficient. “You’re telling us, ‘you’re not good enough to get him home,’” she says.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom: We rely on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.