D.C. Is Poised To Abolish Felony Disenfranchisement

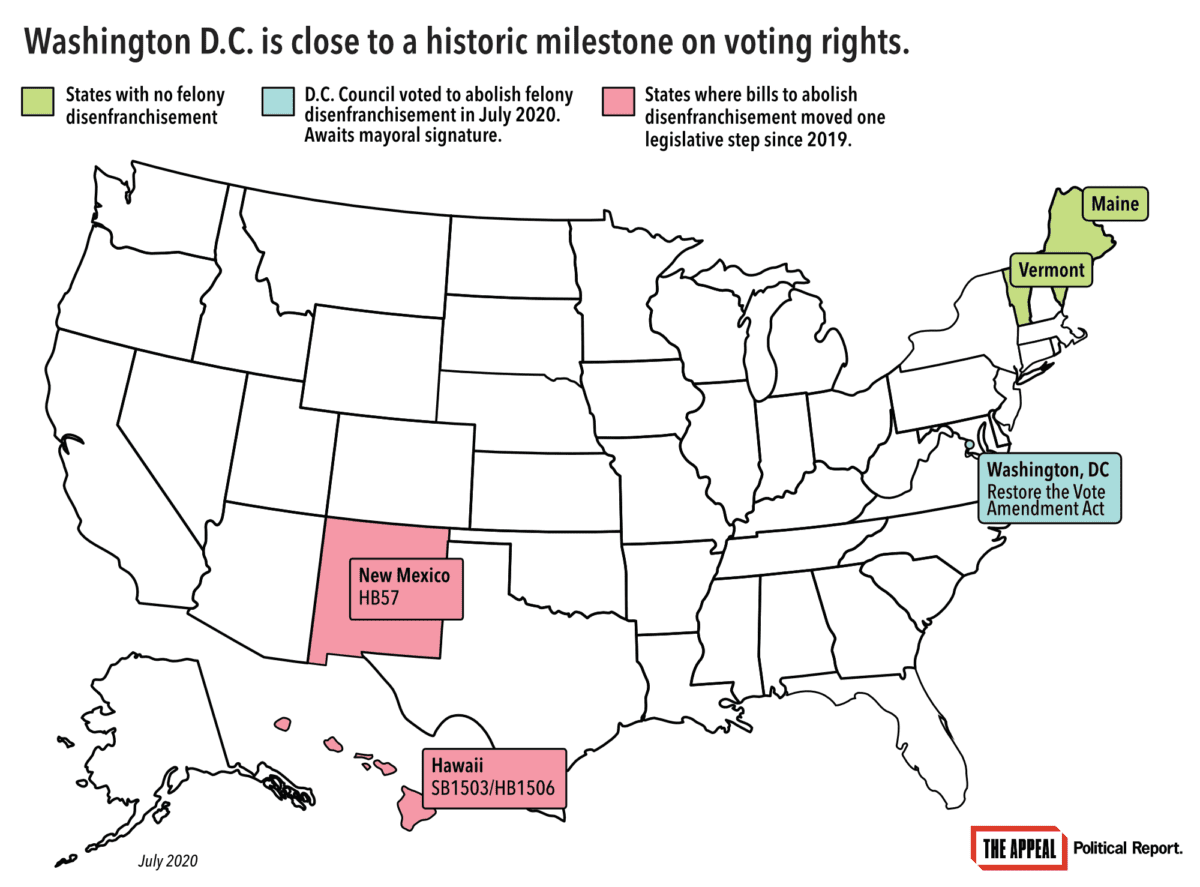

Washington, D.C., is joining Maine and Vermont in allowing incarcerated people to vote.

| July 8, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

D.C. is joining Maine and Vermont in allowing incarcerated people to vote.

Update (July 23): Mayor Muriel Bowser has signed the emergency bill.

The burgeoning national movement to abolish criminal disenfranchisement reached a major milestone on Tuesday, when the D.C. Council approved an emergency bill that would end the practice of stripping people convicted of a felony of their voting rights.

If the mayor signs the bill, Washington, D.C., will join Maine and Vermont as the only jurisdictions to allow all incarcerated citizens to vote.

“Expanding voting rights to persons in prison is a historic step for American democracy,” Nicole Porter, director of advocacy for the Sentencing Project, said in a statement Wednesday.

The emergency bill would immediately restore voting rights to more than 4,000 people. But it would only remain in effect for 90 days without an extension from the council. Councilmember Charles Allen, who wrote the emergency bill, told The Appeal the council will vote later in July on whether to adopt a measure making the change permanent as part of its budgetary process.

The legislation also contains police reforms, including a ban on the use of chokeholds, tear gas, pepper spray, and rubber bullets. But many of the provisions are weaker than those included in an earlier version of the bill that the City Council adopted in June, and which Mayor Muriel Bowser resisted.

The provision ending felony disenfranchisement, the Restore the Vote Amendment Act of 2019, originated as a standalone bill introduced by Councilmember Robert C. White in June 2019.

Under the terms of the new bill, the D.C. government will also be required to provide voter registration materials and absentee ballots to D.C. residents who are in Department of Corrections or Bureau of Prisons custody beginning in January, although prisoners can request and cast ballots for the November election.

D.C. disenfranchises an outsize number of people because it has a higher incarceration rate than any state in the country. As of the end of 2019, 4,049 D.C. residents were incarcerated in BOP prisons, according to the District’s Corrections Information Council, and over 90 percent of them were Black.

Maine and Vermont are the nation’s two whitest states. Washington D.C., by contrast, is the jurisdiction with the highest share of Black residents. White told The Appeal last year that “it’s no coincidence” that states with large African American populations often have strict disenfranchisement policies.

“The majority of states and most Southern states,” he said, prohibited incarcerated residents from voting “right around the time that African Americans were getting the right to vote.”

In 1955, before D.C. had home rule and the ability to pass its own laws, the federal government enacted a law to disenfranchise incarcerated residents. White called that bill “an active effort to disenfranchise African Americans.”

Efforts against felony disenfranchisement have gained tremendous steam in recent years, with six states expanding their electorates since the 2018 midterm election. Among them are three Democratic-controlled states that restored the right to vote to anyone who is not presently incarcerated, enfranchising tens of thousands of voters and bringing the total number of states that allow all people on probation and parole to vote to 18.

But up until now, proposals to altogether abolish felony disenfranchisement have not succeeded, despite some preliminary legislative movement last year in Hawaii and New Mexico and unprecedented debate of the idea in the Democratic primary.

If Washington, D.C., takes the extra step and abolishes felony disenfranchisement altogether, advocates are hopeful it could inspire the pursuit of bolder change around the country.

White emphasized that D.C. politicians would be forced to consider policies that are important to incarcerated people—like prison conditions and the use of solitary confinement—if the right to vote is universal.

“People who don’t have the right to vote generally have their needs ignored, and that’s something we see in our prison systems,” he said.

Many public officials in Maine and Vermont, where incarcerated people already are able to vote, have told the Appeal they share that perspective. “They’re still people, they’re still human beings, they’re still American citizens, and I think this is a process that should belong to every American citizen,” Maine Secretary of State Matthew Dunlap said last year. “And in no small way it helps keep them connected to the real world.”