Pair of Reforms to Expand the Electorate Become Law in D.C.

The city has overhauled its approach to voter registration and also enabled noncitizens to vote in local elections.

Alex Burness | March 17, 2023

In the shadow of Congress and the White House uniting to block criminal-code changes passed by Washington, D.C., two bills that will transform the city’s voting rules became law this week.

One reform, which drew the ire of congressional Republicans, will enable noncitizen residents to vote in local elections. The second largely flew under the radar of national politicians, and will overhaul the city’s approach to voter registration.

Underlying the Automatic Voter Registration Expansion Amendment Act, that seemingly technical bill, is a challenge to a core aspect of U.S. elections. Why put a burden of registration on prospective voters when public authorities can determine who is eligible on their own?

Going forward, D.C. will use the information it collects when residents interact with public agencies like the Department of Motor Vehicles to create a running list of people who are “preapproved” to vote. For people on this list, there will be no need to register in advance of an election; all they will have to do is vote.

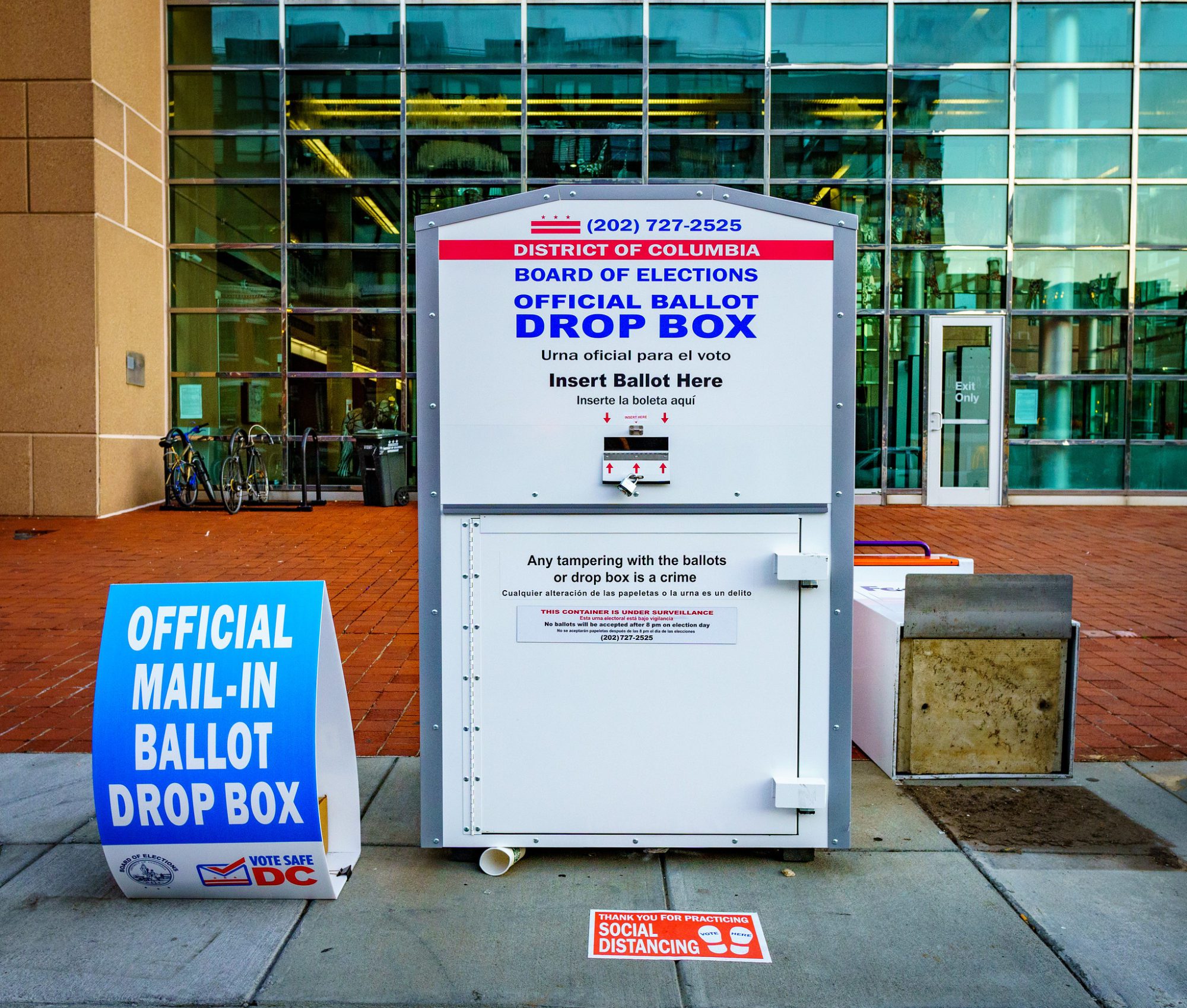

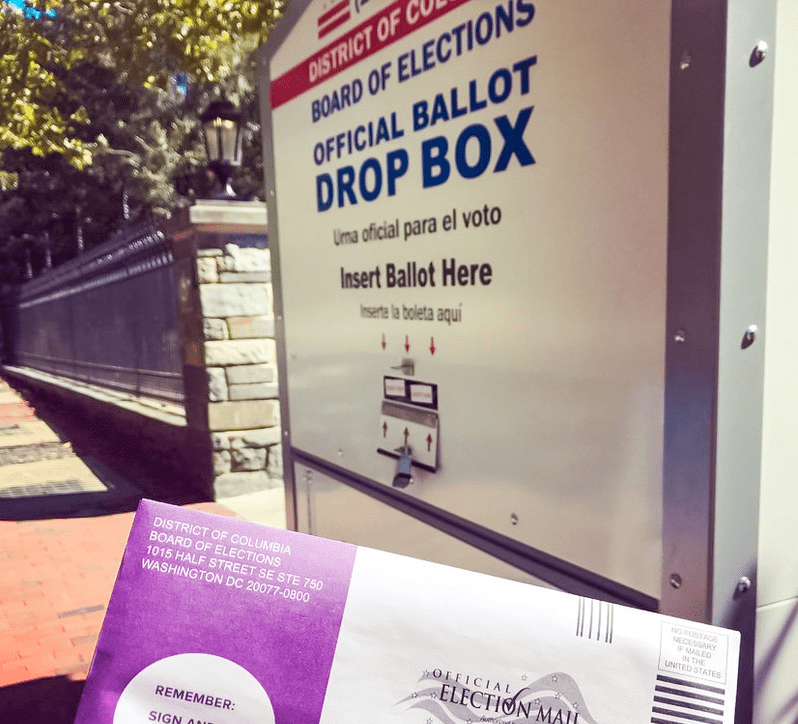

This new law would pair with a reform that the council has adopted but is not yet law, which would set up universal mail-in voting: That bill would apply to people on the “preapproved” list. As a result, D.C. would mail ballots to people it knows are eligible to vote—even if they have not registered.

“Unlike other parts of the country where we’re seeing people try to restrict the ability of people to get to the polls and to vote, in D.C., we want everyone to be able to vote,” Councilmember Charles Allen told Bolts last year when he filed the bill. This act, he said, will “make sure we are really reaching every single person we possibly can to make sure they can participate and have their voice heard.”

The bill was approved unanimously by the D.C. council in December and signed by the mayor. It became law after the customary congressional review that all D.C. bills undergo expired this week. Republicans in Congress did not target this legislation, though they sought to block other recent city reforms, including a bill that enables noncitizens to vote in local elections.

That noncitizen voting bill, known as the Local Residents Voting Rights Act, also became law this week. The U.S. House voted to block it in January in a resolution proposed by the GOP and supported by some Democrats, but the Senate did not follow up by the March 14 deadline that was set by the chamber’s parliamentarian.

As a result, noncitizens who have been residents of D.C. for 30 days will be able to vote in local elections—including for mayor, city council, education board, and ballot initiatives. The law would not apply to federal elections.

“While we’re expanding voting rights here within our boundaries, Congress is attacking our autonomy altogether,” Brianne Nadeau, a D.C. councilmember who sponsored this bill, told Bolts this week. “It’s kind of a wild moment in history.”

D.C. follows at least 15 other municipalities, including Maryland suburbs of D.C. such as Takoma Park, that already allow non-citizen voting. Most recently, voters in Oakland, California, approved a ballot measure in November to enable noncitizens to vote in school board races; in January, Vermont’s supreme court upheld several towns’ decision to enfranchise noncitizen residents.

Similar proposals are on the table in other cities such as Boston. But the GOP is working in several states to preempt such local reforms.

A conservative group filed a lawsuit on Tuesday against D.C.’s new noncitizen voting law, claiming that it “dilutes the vote of every U.S. citizen voter in the District.” Nadeau says she also worries that Congress may still move to block the the funding needed to implement the measure; Congress has budgetary tools available to thwart D.C. measures beyond the congressional review period.

Proponents of the change say that restricting the franchise from noncitizens excludes a large swath of the population from decision-making. The Legal Aid Society of The District of Columbia testified before the council that more than 40,000 D.C. residents are not U.S. citizens, but many of them work, pay taxes in the District, or send children to public schools. They should have a say in their elected government, Nadeau said.

“We have a special opportunity to show that getting involved locally can make a difference,” she said. By getting involved in municipal government, she added, “you can make change in a very short amount of time.”

The Automatic Voter Registration Expansion Amendment Act, D.C.’s other new law, only applies to U.S. citizens. It aims to draw into the process people who are already eligible to vote by building on D.C.’s prior reforms to voter registration.

The city already follows a model known as automatic voter registration, or AVR, along with more than 20 states. The idea is to use the fact that people from all walks of life are already interacting regularly with a DMV and other public agencies for reasons that have nothing to do with voting, like getting a driver’s license. While they’re there, the thinking goes, the government should take the opportunity to register them to vote. Studies have found that this approach boosts registration and turnout rates.

Some automatic registration programs, including the one D.C. currently uses, give residents the chance to opt out of registering while they’re still conducting the transaction with an agency. Many people take the chance to opt out up-front, often because they’re in a hurry and believe that declining will get them out the door faster, or because they may have questions about their eligibility.

The new law switches D.C. into another model, known as “back-end.” Residents who are automatically registered are offered the chance to opt out later on: They will receive a mailer at home, and they can return it if they wish to opt out. If they do nothing at all, they will remain registered to vote.

Colorado made this switch in 2019 and saw its registration rates soar as a result. Testifying last fall in support of D.C.’s change, Colorado Secretary of State Jenna Griswold said that under the state’s prior “front-end” system, roughly 60 percent of eligible residents were opting out. After the switch, Colorado found that more than 99 percent remained registered after receiving the post-transaction mailer.

Allen, the sponsor of the D.C. law, told Bolts he drew inspiration from Colorado.

But his proposal also goes beyond this “back-end” approach. It charts a new path that no longer treats registration as a step that residents must take before voting.

Requiring voter registration, says Alex Keysarr, a Harvard historian who studies the development of voting laws in the U.S., “creates a barrier between the voter and the act of voting.” Historically, he told Bolts, this barrier has suppressed the electoral influence of poor people, immigrants, and people of color.

Under the new law, the city will identify people who, based on information they’ve already provided the government, are eligible to vote. They will then receive a ballot in the mail. For those individuals, the only decision would be to vote, or not.

Still, people added to the “preapproved” list in D.C. would be sent a mailer that gives them an opportunity to remove their name.

The new law also does not get rid of voter registration. The city would inform people that returning the mail-in ballot or heading to the polls would activate their registration. In effect, voting itself would be the act of registration.

But D.C.’s reform may still leave some residents behind since it hinges on them heading into specific public agencies. People who do not interact with the DMV or a Medicaid office would not be added to this “preapproved” list.

“I would caution that there are still people who will not be offered registration opportunities, particularly people who do not interact regularly with government agencies like the driver’s license offices,” said Michael McDonald, a professor of political science at the University of Florida who studies turnout.

D.C. has for years offered same-day voter registration, so those people would have the opportunity to head to a polling location during the early voting period or on Election Day. They would not receive a mail-in ballot, though.

McDonald does not expect the new law to make a major change to turnout in D.C. given the city’s unique circumstances. “The fact that the city is highly uncompetitive and the District has limited self-rule probably matter more,” he said.

D.C. is already facing new attacks on its self-rule. Last week, some House Republicans launched a new push to overturn a set of policing reforms, known as the city’s Comprehensive Policing and Justice Reform Amendment Act, adopted by the D.C. government to expand citizen oversight of police and limit police use of dangerous weapons against protesters, among other provisions.

Nadeau said, “Recent congressional action makes it clear that any of the work we do in the District of Columbia is very precarious as long as we don’t have statehood.”