She Lost Her Right to Vote Over A Felony. Now This Lawmaker Has Helped Enfranchise Thousands.

Tarra Simmons lays out why she championed a new law that restores voting rights to people on probation and parole once she joined Washington’s state legislature.

| April 8, 2021

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Tarra Simmons lays out why she championed a new law that restores voting rights to people on probation and parole once she joined Washington’s state legislature.

Tarra Simmons became the first formerly incarcerated lawmaker in Washington State’s recent history after she won a seat in the state House in November. Five months later, she is celebrating her first win as a legislator: A bill she sponsored was signed into law yesterday by Governor Jay Inslee, who credited her advocacy. It enables all formerly incarcerated Washingtonians to vote.

“This bill helps bring more people into the fold of influencing policy,” Simmons said in a Zoom interview about the new law. “Hopefully that leads to more people participating in a bigger way by coming to Olympia and sharing their voice and their experiences, to continue to stand up for the things that matter most to them and their community.”

Until now, Washington State barred residents convicted of a felony conviction from voting as long as they were in prison, on parole, or on probation. The new law restores the voting rights of people who are on parole or probation; it effectively enfranchises anyone who is not presently incarcerated. Had this law been in effect during last year’s elections, it would have benefited roughly 24,000 people who were barred from voting, according to estimates by the Sentencing Project.

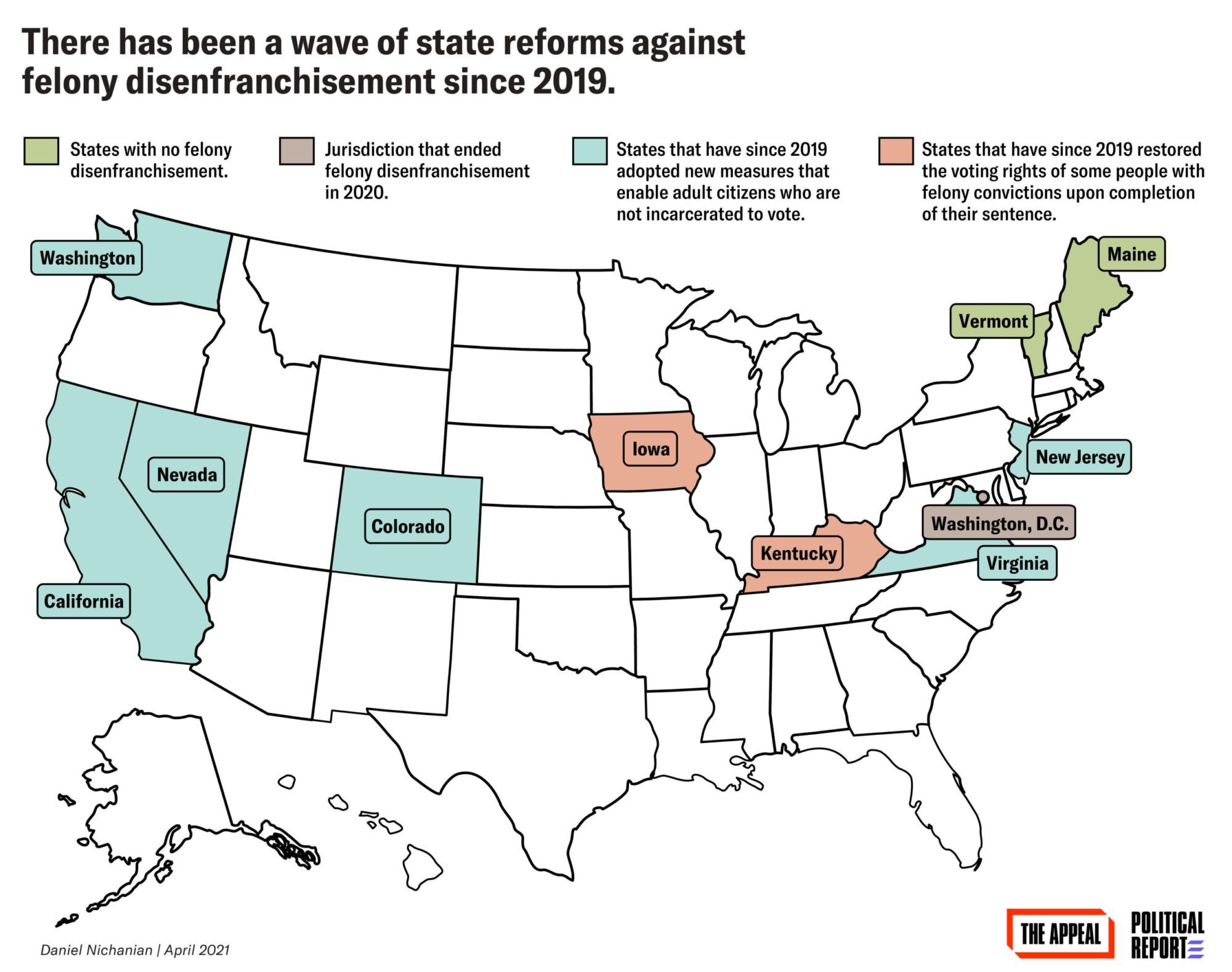

Washington is the 20th state to adopt statutes that enable everyone who is not incarcerated to vote—and it is the fifth state to get there since 2019, after California, Colorado, Nevada, and New Jersey. (Also, New York and Virginia’s governors have issued executive orders that approximate this policy.) Two of those states, plus Washington, D.C., also enable people with felony convictions to vote from prison.

Before she joined the legislature, Simmons worked as an advocate for loosening the barriers faced by people with criminal records. Her own experience after being released from prison over drug offenses, she recounts, involved struggling to find jobs. She battled up to the state Supreme Court to secure her right to take the state’s bar exam. She attributes her efforts to champion voting rights to these struggles.

“It made me feel like I wasn’t a part of my community,” Simmons says of her reaction when she lost the franchise. “I feel that way still when I can’t rent an apartment or I can’t go on a field trip with my kids, those things that other people take for granted but that convicted people don’t get to enjoy.” Such restrictions, she said, harm public safety by destroying economic and housing security, making it harder “to provide safety for my kids,” and provoking cycles of instability.

Now Simmons wants Washington State to go further and enable people to vote from prison as well.

“Maintaining ties, believing and having hope that you are still part of something larger, is really important,” she said.

The following interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

—

You’ve often talked about the obstacles you faced after your arrests and incarceration. What did losing the right to vote specifically mean to you?

It made me feel like I wasn’t a part of my community, like I didn’t have basic rights other people enjoy. I feel that way still when I can’t rent an apartment or I can’t go on a field trip with my kids, those things that other people take for granted but that convicted people don’t get to enjoy.

This bill helps bring more people into the fold of influencing policy. And it will make our policy stronger if we have directly impacted people involved in making and influencing the policy.

I want them to continue to go on a positive path, get engaged in their communities, and find a way to use their voice to influence change. I think we get that initial connection with voting, learning about candidates and issues and then weighing in, but hopefully that leads to more people participating in a bigger way by coming to Olympia and sharing their voice and their experiences, to continue to stand up for the things that matter most to them and their community.

That’s something that reform advocates talk about elsewhere in the country, that their work is made harder because legislative hearings typically don’t make room for the voices of people who are impacted and people who are incarcerated.

Absolutely. If you’re not a voter, an elected official will not necessarily see you as an influential voice or feel accountable to you. I started doing advocacy here in Washington five or six years ago, and I created a nonprofit to get more directly impacted people involved in policy-making on issues that impact our lives. If not, you have a lopsided policy argument of policy debate that doesn’t center the people that are directly impacted.

Did this advocacy help push the new voting rights law across the finish line this year?

A large coalition of directly impacted people have spent so much time for the last year educating the public, building support, and educating my colleagues. Several victim organizations also signed onto letters of support for this bill, saying that this had nothing to do with public safety. If anything, it has a net gain for public safety by not making people live underground when they come out of prison.

Could you say more about that? How do difficulties upon leaving prison, which you have often talked about, interact with safety?

Safety, to me, is economic and housing security, to where I’m not vulnerable to greedy people, have stable employment and enough money to support my family. And the criminal record is a huge barrier to that. It continues to pop up at every opportunity for meaningful gainful employment where I make enough to provide safety for my kids.

This is why generational cycles happen—generational trauma, generational poverty—because it’s so hard to get out with the criminal record. It’s not okay to discriminate based on race or gender or sexual orientation, but convicted people don’t have those same civil rights protections, and this is why we’re seeing the cycles of poverty, trauma, and incarceration play out in families.

One thing this bill doesn’t touch is the voting rights of people who are still incarcerated, which is a right in Maine, Vermont, and Washington, D.C., and is now under debate in Oregon. Do you want to see Washington State take that step?

Absolutely. I think that felony disenfranchisement is rooted in Jim Crow-era laws and that we need to undo that as well. If people that are currently incarcerated were seen as a constituency, lawmakers would be paying more attention to what’s going on inside of our prison system, which is filled with inequities and dehumanizing conditions.

Every little thing we can do that helps people maintain some form of humanity and feel like they’re connected to something outside the prison walls is a good thing that will help set them up for success upon reentry. And that’s what we’re hoping to do: Our prison system is not supposed to be purely punishment, it’s also supposed to be rehabilitative. Maintaining ties, believing, and having hope that you are still part of something larger is really important.

And so I absolutely support following the lead of Maine, Vermont, and Washington, D.C., and getting rid of disenfranchisement altogether.

According to the Sentencing Project’s estimates nearly 4 percent of Black adults are stripped of the right to vote in Washington State, compared to less than 1 percent of the entire population. That reflects huge disparities in who is being convicted of a felony in the first place. How should Washington State fight these racial inequalities?

Almost all of our sentencing laws have racial disparities. And it goes back to policing and bias in policing, it goes to inequities in education and school, the use of school resource officers—I mean, how far back do you want to go? Do you want to go back to postpartum inequities and how Black mothers are dying at higher rates? The racial disparities throughout all of our systems are leading up to the inequities in the criminal legal system. But we’re not getting upstream enough. That’s why I ran for office, to get out of just cleaning up the inequities on the back end with collateral consequences and into upstream investments.

Washington State’s Supreme Court struck down statutes criminalizing drug offenses in February. This has vacated thousands of felony convictions. It’s also created a debate about what the legislature should do next, including some lawmakers who argue drug possession should be a felony again, and others who want to at least decriminalize drugs, as Oregon did in a 2020 referendum. What do you think should be next on this issue?

I would like to see more robust behavioral health responses to treating this public health crisis and less reliance on the criminal legal system, which is a very traumatic and dehumanizing process for people that are already suffering. I am absolutely in favor of at a minimum going as far as Oregon did. The [quantity] limits in the Oregon legislation are very arbitrary in my professional opinion and personal experience. I was no less a person suffering from substance use disorder when I purchased my drugs on day one or when I was running out on day three.

We’re negotiating a lot of different options right now, and I have to be there as the lone voice, reminding them that I have a felony drug possession and how it’s impacted my life.

Let me return to voting rights. We’re having this conversation at a time many states such as Georgia are passing bills that restrict the right to vote. Washington State’s new rights restoration law goes in the other direction; it expands the electorate. What do you make of this contrast?

I’ve been thinking about the differences between what’s happening in Georgia and in Washington. In my opinion, it’s all based on race. Throughout history, there’s always been a group that has been trying to expand democracy and a group that’s trying to restrict it, and in my opinion it is all about white supremacy. Who wants to stand on the side of equity and justice and who wants to maintain power of and uphold white supremacy?

—

Find out about other recent rights restoration reforms.