What Does it Mean to Take Politics Out of Prosecution?

The incoming prosecutor of Pierce County, Washington says the job ought to be nonpolitical, but her campaign also illustrated the limitations of this common trope.

| December 13, 2018

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Mark Lindquist, the Democratic prosecuting attorney of Pierce County, Washington (a populous county home to Tacoma), suffered an uncommonly large defeat for an incumbent in November. He lost 63 percent to 37 percent to independent candidate Mary Robnett, an assistant attorney general. Lindquist’s ethics were at the forefront of the campaign. In 2015, whistleblower complaints against Lindquist led to an external investigation that documented a toxic work environment within the prosecutor’s office and retaliation against critical employees and defense attorneys. This year, Lindquist received an admonition from the Washington State Bar Association for a separate complaint against remarks he made in 2016 on the TV program “Nancy Grace” about a murder trial that his office was prosecuting.

In her challenge to Lindquist, Robnett emphasized that prosecutors ought to be nonpolitical. Her website stated that she “strongly believes that politics doesn’t belong in the Prosecutor’s Office. Crime is not partisan. Justice shouldn’t be political.”

But Robnett’s campaign also illustrates the limitations of this commonly used trope.

For one, it ignores the policy decisions that actors involved in the criminal justice system are constantly making. Robnett’s platform has no statement regarding how she would exercise her vast discretion, for instance when it comes to charging decisions or bail; in fact, it displays no recognition of the policy freedom that prosecutors have. Moreover, in highlighting how the campaign is apolitical, Robnett’s website prominently features the support of police unions, as though these groups did not themselves have a politics. “Mary has received the endorsement of every police organization that is endorsing in this race,” says her website. But many of the organizations listed were simultaneously opposing Initiative 940, the referendum that lowered the threshold to prosecute police officers for using excessive force.

This trope reinforces the expectations that the main axis on which to differentiate within prosecutors is whether they are competent and exercise good governance, and that prosecution is mainly about obtaining convictions. The website’s main criticism of Lindquist’s prosecutorial practices are that he “has the highest number of overturned guilty verdicts”; and it highlights Robnett’s experience “handl[ing] some of Pierce County’s biggest cases and worst criminals.”

This framing also downplays the criminal justice system’s broader problems. Robnett pledged to transform the prosecutor’s office in terms of overcoming Lindquist’s tenure as a rogue public official. “We deserve a Prosecutor like Mary, a professional who is focused on crime, not image management and climbing the political ladder,” says her platform page. But Robnett skipped two of a trio of questions about how she would address the “epidemic of over-incarceration” in one candidate questionnaire; in answer to a third, she only mentions increasing the use of diversionary programs and drug court.

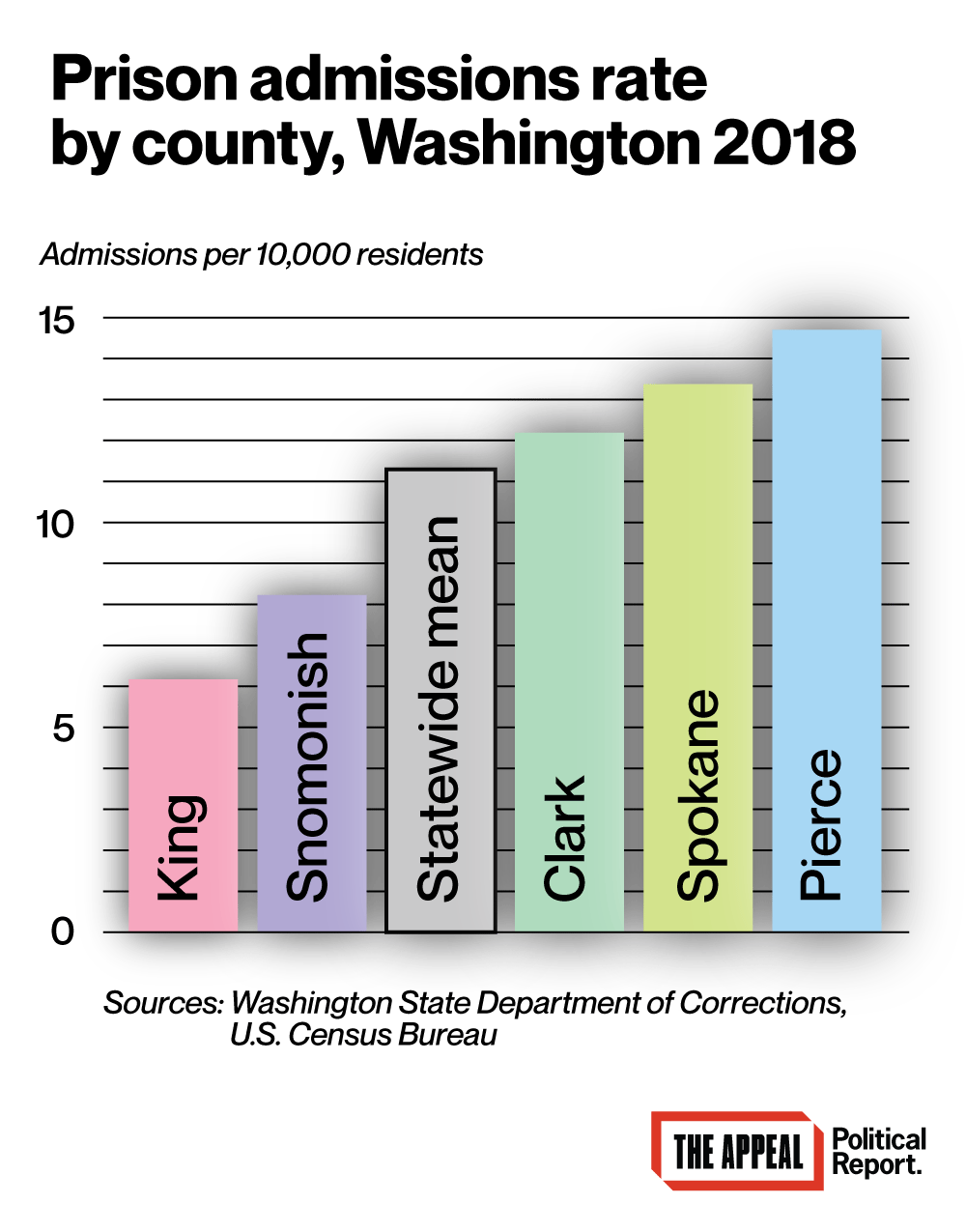

But this question was an important one. Of Washington’s five most-populous counties, Pierce has the highest number of prison admissions per capita, according to statistics released by the state Department of Corrections. And in filing a class-action lawsuit in 2017 against the way in which the Pierce County Jail treats people with mental illnesses, the ACLU of Washington condemned the county’s “revolving door of incarceration.”

Whether the policies implemented by the incoming prosecutor reinforce or reverse these patterns of mass incarceration will be central to assessing Robnett’s tenure. But confronting these problems will require going beyond targeting a set of exceptionally rogue practices.