A Supreme Court Race May Shuffle the Rules of Wisconsin’s Democracy, Again

Two years after liberals flipped this supreme court, ushering in a new era on election issues from gerrymandering to drop boxes, conservatives hope to win it back in April.

| February 14, 2025

T.R. Edwards grew up with stories from his grandmother Kathleen about her struggle to vote as a Black woman in Wisconsin: A child of the Jim Crow south, she’d moved to Madison in the 1970s, and then to Milwaukee, with no birth certificate, which made it hard to prove her identity for government purposes, including voter registration. It took her more than 20 years to finally resolve the matter and, in 1992, she became the first person in her family to vote.

Decades later, when T.R. started working as a voting rights organizer in Milwaukee, he was dismayed to find versions of his grandmother’s story all over the city, with young adults and old folks alike struggling to meet the state’s rules for proving their identity, a prerequisite to voting, particularly on the majority-Black north side of town. This became much more of a barrier after 2011, when state GOP lawmakers passed a law that made Wisconsin’s voter ID rules among the strictest in the nation.

The Wisconsin Supreme Court upheld the law ahead of the 2016 presidential election, on the grounds that the legislature “has the power to say how, when, and where a qualified elector may vote.” A subsequent University of Wisconsin study found that up to 28,000 people—disproportionately Black and low-income—in the overwhelmingly Democratic areas of Madison and Milwaukee were deterred or outright blocked from registering to vote that year because of voter ID rules; Donald Trump won the state in 2016 by about 22,750 votes.

Wisconsin’s attorney general at the time, Republican Brad Schimel, boasted that those requirements were crucial to his side’s victory, telling a local radio station that Trump may not have won the state “if we didn’t have voter ID to keep Wisconsin’s elections clean and honest and have integrity.”

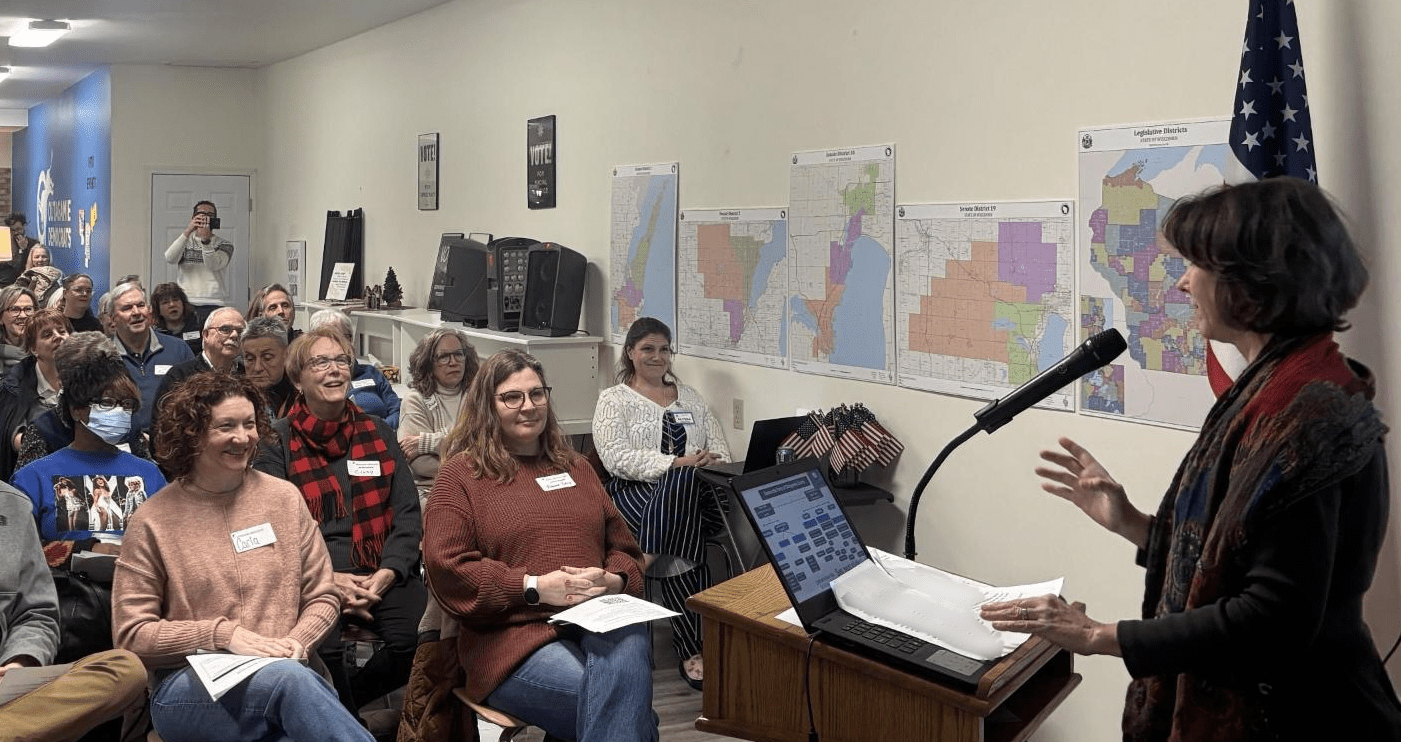

This year, Schimel is running to join the Wisconsin Supreme Court. He faces an opponent, Susan Crawford, who as an attorney helped lead the challenge to the state’s voter ID law in court.

“One of the things that we were pointing out in some of the litigation on the voter ID law is that what’s easy for some people is not easy for others,” Crawford, now a circuit court judge in Dane County, told Bolts this week. “For elderly people, people who have disabilities, people who have unstable housing, something like producing an ID can be a really big challenge. For somebody like me, it’s no big deal.”

“We need to look out to protect the rights of all voters, not just the ones for whom something like showing your driver’s license is not a problem,” she said. Crawford added that she could not comment on the state’s current voter ID rules, pointing to some changes in state law since her lawsuit.

Schimel, now a circuit court judge in Waukesha County, did not respond to multiple interview requests from Bolts.

For T.R. Edwards, who is now a staff attorney with the Wisconsin pro-voting rights group Law Forward, Wisconsin’s voter ID law makes the work of engaging voters much more difficult.

“You don’t truly have a democracy if people can’t actually access the right to vote,” he told Bolts. “Do we want a democracy that’s narrow and specifically tailored to benefit the people who already have power and privilege, or do we want a democracy that legitimately includes everyone?”

That, in so many words, is a question the Wisconsin Supreme Court has often been asked to consider.

This court has recently leaned in favor of expanding voter access and making democracy more representative. In 2023, it threw out gerrymandered Republican legislative maps that had locked the GOP in power. In 2024, it allowed ballot drop boxes to return to Wisconsin, reversing an earlier ruling. Last month, it ruled against a conservative activist who had sought voters’ private information in order to hunt for ineligible voters and build the case that Wisconsin elections are fraudulent.

This new tendency in support of voting rights was catalyzed by the 2023 victory of Janet Protasiewicz, who gave liberal justices a 4-3 majority over conservatives. (Supreme court elections in Wisconsin are officially nonpartisan.) This flipped the court to liberals for the first time since at least 2008.

But control of the court is on the line once more because a longtime liberal justice, Ann Walsh Bradley, is retiring this year. The April 1 contest between Crawford and Schimel will decide whether conservatives win back a majority.

Abortion and labor rights have dominated the campaign narrative so far because the court is currently deciding challenges to a 1849 ban on abortion and to a 2011 law, known as Act 10, that restricted collective bargaining. These candidates represented opposing sides in past litigation around Act 10, with Crawford helping a lawsuit against it and Schimel working to defend it. Schimel also has a long history of supporting a ban on abortion, while Crawford is running ads saying she has “fought for abortion rights.”

Both candidates are touting their “law-and-order” credentials and arguing that they’re tougher on defendants than one another. On other issues, they’ve stressed stark differences. Schimel is running an avowedly conservative campaign: His website slams the judicial system for “opening the border,” warns of the court “forcing biological males into girls’ bathrooms” if he loses, and blares in large block letters “SAVE THE COURT.”

Crawford, by contrast, is running with the endorsements of the four liberal justices on the court today, plus that of major labor unions. She’s also endorsed by Planned Parenthood, a group she represented in a 2014 lawsuit concerning non-surgical abortion.

But voting rights advocates are closely watching the election as well. A host of issues related to voter access—the use of drop boxes, accommodations for disabled voters, and voter ID rules, to name a few—may also ride on this court’s composition.

“The latest makeup of the court has been a major pro for access to democracy,” said Sam Liebert, a former Wisconsin election clerk who now directs the state chapter of the pro-voter access group All Voting is Local. “It’s so important that we have a supreme court that recognizes that the right to vote is a right.”

Conservatives have also drummed up attention to the April contest’s importance for elections policy. “Very important to vote Republican for the Wisconsin Supreme Court to prevent voting fraud!” Elon Musk posted on X in January, echoing the right’s unfounded claims that Wisconsin elections are fraught with fraud.

“Elon Musk highlighted a critical issue in this race: election integrity,” Schimel told a conservative radio host.

Schimel built a record of controversial actions in the name of “election integrity” when he served as attorney general. In 2016, he dispatched state Department of Justice employees to monitor polling sites, mostly in heavily Democratic areas—a move Democrats and voting rights advocates criticized as an intimidation tactic against communities likely to oppose Trump.

Crawford, meanwhile, says she supports making it easy to vote. “The bottom line is that we need to make sure that eligible voters are able to exercise their right to vote without having to jump through a lot of unnecessary hoops,” she told Bolts.

She added that she is generally wary of policies that purport to make elections more secure but that mainly just hamper voters: “I think it is really important, obviously, that we have fair elections in Wisconsin, and that includes elections that are safe and secure, but also elections where everyone who is eligible to vote can exercise that right and get their ballots cast,” she said. “There needs to be a balance there and the law needs to be used to protect both aspects of elections.”

There’s currently no case pending in front of Wisconsin’s supreme court concerning the voter ID requirement, though Schimel’s campaign has played it up as a live issue. Some prominent supporters have also tied the race to false claims that drop boxes for mail ballots are a vehicle for voter fraud, arguing that Wisconsin’s ability to limit voting by drop box depends on a Schimel victory.

That may be true: In the run-up to the 2024 presidential election, the Wisconsin Supreme Court issued a 4-3 decision that let Wisconsinites deposit their mail ballots at drop boxes. That ruling reversed a 2022 ruling that had banned drop boxes in that year’s midterms. Protasiewicz’s victory and the court’s flip in 2023 made the difference between those two cases, and observers think a conservative majority could revisit the issue ahead of 2026 if the court flips again this year.

The highest-profile voting issue this court handles may be redistricting, which dominated the 2023 race Protasiewicz won, and which led the GOP to threaten to impeach her. The court struck down the previous legislative maps as being non-contiguous, and kicked the matter to lawmakers who, fearing potential court-ordered maps friendly to Democrats, ended up adopting fairer statehouse maps in 2024 that paved the way for Democratic gains amid much more competitive Wisconsin elections last fall. Democrats now see an actual chance at winning legislative control in 2026.

Several experts told Bolts that it’s unlikely the statehouse maps would change again before 2026, even if conservatives regain control of the court. That’s because the maps were technically adopted voluntarily by lawmakers, and, these experts said, Wisconsin law doesn’t provide a significant opening for a mid-decade challenge to the maps.

“This may be hopelessly naïve, but I actually think the maps are effectively set for the new decade, and aren’t going to change based on the state Supreme Court alignment,” Justin Levitt, a professor at Loyola Law School who has deep experience in redistricting litigation, told Bolts.

Still, the victor will have a 10-year term, meaning they’ll be seated during the next round of redistricting in 2031 and could affect decisions on whether the maps the state uses in the 2030s are gerrymandered. Five other seats on this court will be up for election by the 2030 Census, giving each side more opportunities to win a majority by then.

One of the three conservative justices currently on the court, Brian Hagedorn, has occasionally sided with liberals, which may blunt the effect of a right-wing majority in some cases if Schimel prevails on April 1. And despite its polarization, the Wisconsin Supreme Court also has had a recent history of moving cautiously, including on voting issues, Wisconsin Watch showed in an analysis published last month.

Still, elections for this court have become increasingly intense. Crawford and Schimel have combined to raise more campaign cash so far this year than their counterparts had raised by this point in the 2023 race that Protasiewicz won—which, at about $50 million, was the most expensive state judicial contest in American history, and by far the most expensive in Wisconsin history. (The previous state record, set in 2020, was $10 million). State judicial races in general are quickly becoming more costly in this country, particularly after the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dobbs striking down federal abortion protections.

“We here on the ground in the state have understood supreme court elections to be, essentially, proxy battles in the larger political or ideological war that’s been taking place here for quite some time,” Chad Oldfather, a constitutional law professor at Marquette University in Milwaukee, told Bolts. “It may be getting even more openly so.”

Well aware of the stakes of this race, and of the additional loss of legislative power they may suffer soon in the absence of gerrymandering, Wisconsin Republican lawmakers have taken steps to enshrine some of their preferences into the state constitution. The legislature, controlled by the GOP in both chambers, has advanced four different elections-related constitutional amendments to the ballot since 2023.

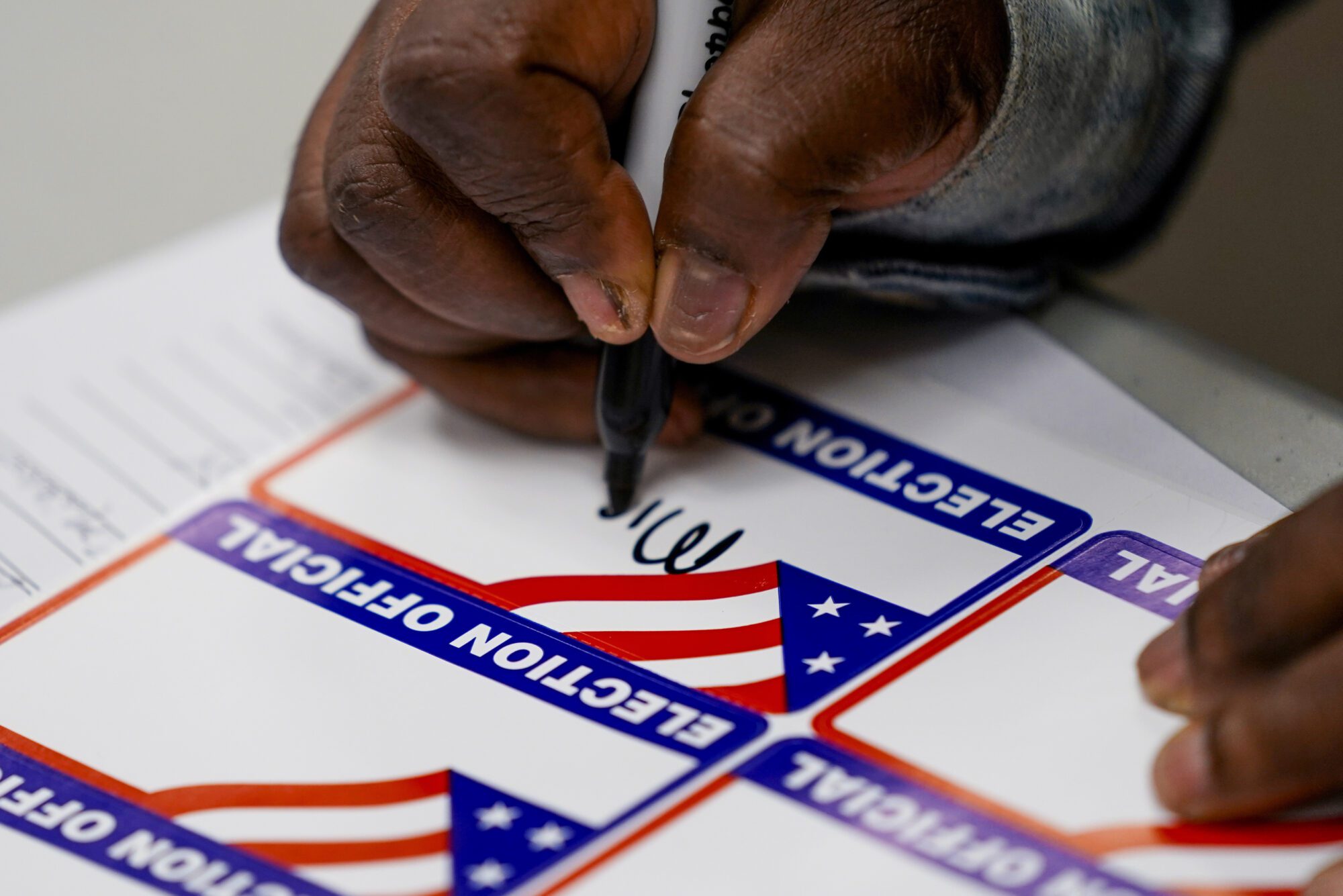

Three have already passed; they ban outside funding of election administration, strictly define who can qualify to be an election worker, and ban on noncitizen voting in Wisconsin.

The fourth, which will be on the statewide ballot in April alongside the supreme court race, would codify voter ID requirements.

Democrats have accused Republicans of pairing the court contest with this ballot measure, which would simply reiterate existing law in the state constitution, in order to juice turnout among conservatives who are avid about voter ID. The Republican state senator who sponsored the ballot measure told the Associated Press this year that he was “not willing to risk” a voter ID challenge coming before a liberal court in the future. “We can be sure that a new lawsuit challenging its constitutionality is coming,” the senator, Van Wanggaard, said.

Oldfather told Bolts that Wisconsin Republicans are hoping to tie the court’s hands by convincing voters to enshrine voter restrictions in the state constitution. “You can’t find something unconstitutional if it is part of the constitution,” he said.

Even when a constitutional amendment passes, the court still has a role to play in interpreting it. The 2024 measure to restrict who can work on elections, for example, threatens to diminish staffing and hamstring local clerks, but the vagueness of its language has created confusion that the court may need to address, several Wisconsin experts told Bolts.

Voting rights attorneys and their opponents are closely monitoring the race and will tailor future suits according to its outcome, T.R. Edwards predicted.

“We have to understand the dichotomy between that foundational right to vote and these new restrictions and rules,” he said. “In the next few months, years, there will very likely be litigation to affirm that right.”

Over his decade doing voter outreach in Milwaukee, Edwards said, he saw constantly how barriers to voting—including the informal barrier of widespread confusion regarding eligibility—suppress democratic participation. He spoke of students without drivers licenses who live in group homes and cannot produce utility bills or anything else to prove their residence, of people who have no idea what they’ll need to obtain in order to vote, and of people who simply give up before even trying.

“Every extra hurdle that you put in place is just one more reason, one more challenge, that a voter has to face,” Edwards added. “To be able to ensure that people can actually access the ballot box, we need a court that understands this.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.