Parole Plunges in South Carolina as Governor-Appointed Board Issues Denial After Denial

People familiar with South Carolina’s parole process describe a secretive panel that downplays rehabilitative efforts and ignores applicants’ attempts to correct their files.

| June 3, 2024

After appearing before the South Carolina Board of Paroles and Pardons more than 500 times in the past 35 years, lawyer Douglas Jennings announced last year that he had participated in his final hearing. It had become routine for the board to reject his clients, regardless of how much he showed that they’d changed since their crime. “I just couldn’t justify taking somebody’s money as a fee to appear before the parole board when I didn’t feel good about being able to produce the right results for them,” he told Bolts.

The panel, which Jennings has nicknamed “the rejection board”, has made it increasingly difficult for prisoners to win parole in South Carolina. In 2018, it released roughly four out every 10 people who applied. The odds of release have declined since then: By 2022, the board only approved one out of every 10 petitions. Last year, the board’s grant rate was seven percent.

This downward trend has continued into 2024. In the first four months of this year, the board approved only 5 percent of more than 900 parole applications, according to data provided by the board.

Declining parole rates in South Carolina are part of a national trend. Parole, which permits early release for eligible prisoners who exhibit good behavior and have a low risk of committing another crime, has fallen across the country in recent years as parole boards have succumbed to political pressure and media narratives that stoke fears about crime. Between 2019 and 2022, grant rates plummeted in 18 out of 27 states surveyed by the the Prison Policy Initiative, a criminal justice reform research organization. Often, this decline has directly stemmed from state officials’ desire to crack down on release, and to the professional and ideological backgrounds of the people they appoint to parole boards, as Bolts has reported recently about the parole boards in Alabama and Virginia.

The same political dynamic is at play in South Carolina. Governor Henry McMaster, a Republican who in 2016 proposed abolishing parole when he was attorney general, is in charge of appointing the board’s seven members, pending Senate approval, and can remove them at his discretion. Under his tenure, the members he’s put in place have operated a system that places an emphasis on past crimes rather than rehabilitative efforts.

They’ve also kept crucial details about their operations secret, Bolts learned from interviews with people who’ve experienced the process and from analyses of past cases. In some cases they’ve denied parole based on incorrect information, ignoring applicants’ efforts to correct their files.

As chances for parole shrank in South Carolina, Jennings grew tired of trying to convince board members that his clients had worked on bettering themselves in prison and would be productive members of society, only for the board to routinely reject their applications because of their past crimes. “The board seems to have adopted some sort of super conservative approach of not really giving a fair opportunity of parole to many inmates who would pose no risk to the community,” he said.

In South Carolina, parole has long already been an unfair process. The University of Pennsylvania Journal of Law and Social Change published a study this month finding that Black people in the state were denied parole at significantly higher rates than their white counterparts from 2006 to 2016. More than 60 percent of the state’s prison population is Black compared to 27 percent of the statewide population.

People hoping to get paroled in South Carolina must navigate a complicated and adversarial system. Those who committed nonviolent offenses have to win unanimous approval from a panel of three board members or a majority of the full seven-member board. Prisoners convicted of a violent crime go before the full board and must win a two-thirds majority, or at least five members. Historically, the board has granted parole to people convicted of nonviolent offenses much more frequently than those convicted of a violent crime.

This year, though, board members have rarely voted in favor of parole regardless of the nature of the crime.

The board declined to answer Bolts’ questions about the falling grant rates; board spokesperson Anita Dantzler wrote in an email that it “does not participate in public interviews.”

Critics of the parole board say many of its members are skeptical of parole across the board, with little regard for individual circumstances; they also worry that, for some members, this has to do with careers far removed from the criminal legal system. Kim Frederick, the board’s chair since 2019 who has a background in victims services, granted just 41 of the 849 parole applications she reviewed this year, an approval rate of 4.8 percent, according to data obtained by Bolts showing members’ voting record from January through April of this year.

Frank Wideman, a philanthropist who has served on the board since 2021, granted parole to just 3.8 percent of prisoners, the lowest grant rate among the board members so far this year. Reno Boyd, a high school math teacher, paroled 6.3 percent of applicants. Molly DuPriest Taylor, a family lawyer, approved 6.5 percent of applications, while Henry Eldridge, who formerly worked in pharmaceuticals, approved 8 percent. Geraldine Miro, an interim board member since 2022 who formerly worked in corrections, granted the most petitions this year, with 9 percent.

“A majority of the members do not believe in parole,” said John Blume, a Cornell University law professor who has represented prisoners sentenced to life without parole as children in front of the parole board.

Though supporters are allowed to speak in favor of parole during hearings, board members heavily rely on a file that’s weighted toward prisoners’ prior offenses. The file includes, among other things, a summary of the crime, law enforcement statements, and victim statements. Prisoners and their lawyers don’t have access to the victim statements.

Parole lawyers say that since last year, prisoners have only been allowed to submit 20 pages of supporting documentation such as letters, yet there’s no limit to what goes into law enforcement’s and victims’ accounts.

It’s mandatory for prisoners to sign a form acknowledging that it’s their responsibility to notify the board if something in the packet is inaccurate. But prior to this spring, prisoners weren’t even permitted to review their files—a change that was forced by a court order. Even now, prisoners and their lawyers can’t access the file until the morning of their hearings. If they find mistakes within the file, any corrections they want to make have to be backed up with an official record, making it nearly impossible to ensure the parole board receives accurate information.

“Obviously, there’s no way to substantiate with the official record when you’re at the prison at nine o’clock in the morning and your hearing is in 30 minutes,” said Allison Elder, executive director of Time Served, an organization that provides free representation for parole hearings to people incarcerated in South Carolina.

Elder said she has seen files that list prior offenses that never occurred and don’t include mitigating details about a crime that may be helpful for the board to understand. But because the hearings are so short, sometimes lasting just five minutes, and she wants to focus on making the case for parole instead of debating inaccuracies, it’s difficult to make sure her clients are getting a fair hearing. The lack of a mechanism to correct the record during a hearing is “entirely problematic,” she said.

Board members are supposed to consider a risk assessment tool that predicts prisoners’ probability of re-offending. Defense lawyers told Bolts that the board is ignoring those evaluations. Elder said she’s reviewed files that show her clients were scored a low risk yet the board has repeatedly denied them parole.

Prisoners trying to convince the board they’re fit for release also haven’t been able to personally appear before board members deciding their fate since the pandemic and can only make their case by video, making their plea even more impersonal. “We say all of the time, if the board members could just come and sit with our clients for 30 minutes, we would get more votes,” Elder said.

The dwindling chances at parole have taken a toll on prisoners. Elder recalled a recent conversation with one of her clients, who told her, “There is no hope here.”

“It causes depression, devastation,” Elder said. “I’ve seen psych notes about my clients where they go to mental health after having lost out on an opportunity for parole for the umpteenth time.”

Larry Blackwell, who has been serving a life sentence for murder since 1992, was a model inmate for more than a decade before going up for parole in 2014. He had gotten sober, was living in a character-based unit focused on rehabilitation, and had gone 15 years without being disciplined by prison staff.

Despite his successes, a false allegation that made it into Blackwell’s file a decade ago has blocked him from winning his freedom.

In spring 2014, Barry Barnette, the solicitor for Spartanburg County who helped prosecute Blackwell, received a letter from a prisoner using a fake name who accused Blackwell of making inflammatory comments about the prosecutor. “Larry has spoke so nasty of you,” according to a copy of the letter filed in court. “Said he wish he could get you wife drunk, have sex, and video it and sent it to you.” The letter suggested that Barnette tell the local sheriff and senator, and said, “perhaps yourself can oppose Larry’s parole attempt.”

The prosecutor immediately contacted the South Carolina Law Enforcement Division (SLED) about the letter. While they investigated, Barnette sent his own letter to the parole board asking members to deny Blackwell’s release—erroneously claiming that “fellow inmates” had informed him of death threats by Blackwell. “Mr. Blackwell has recently threatened to kill me and my wife,” Barnette wrote to the board, which denied Blackwell parole.

Blackwell told state police investigators that he suspected the letter had come from Alan Yates, a prisoner who had sent similar letters trying to implicate other prisoners in the past. When questioned by investigators, Yates eventually confessed to writing the letter but maintained Blackwell had bragged about assaulting Barnette’s wife. According to the SLED report, Yates asked to be moved to another prison as a reward for informing on Blackwell. Instead, he faced disciplinary action for sending the letter under a false name. Investigators concluded their probe following Yates’ confession and sent their findings to the attorney general, who declined to prosecute Blackwell for any wrongdoing in the matter.

Despite the SLED report that did not find any wrongdoing by Blackwell, Barnette still sent letters to the parole board three more times over the following years, falsely informing them that Blackwell had threatened to kill him and his wife. The board continued to deny Blackwell parole.

Blackwell’s lawyer, Jon Ozmint, tried to make the board aware of the SLED report documenting the ordeal prior to his hearing in 2021 but the general counsel refused, saying that he had conducted his own investigation into the allegations, which included talking to Barnette. The board’s general counsel concluded that the report didn’t clear Blackwell.

During the hearing, Ozmint still told the board that Barnette’s letter contained false information and that SLED had cleared Blackwell. After board member Taylor asked for the report, the board’s general counsel gave it to the panel but reiterated that he didn’t think it was exonerating. “I spoke with Solicitor Barnette about this, he stands by his statements to the board,” said the general counsel, according to a court filing.

Board director Valerie Suber meanwhile questioned the validity of the SLED report, reminding members that it was given to them by Blackwell’s lawyer, not an official from SLED. “This is simply something that his attorney supplied to us in order to refute a statement of [opposition] and we don’t investigate or legitimize statements of opposition,” she said, according to a court filing.

Blackwell’s team has alleged that those actions violate this due process rights but have struggled to find someone in power who agrees.

He challenged the board’s decision in the court responsible for overseeing state agencies, but the court ruled that it didn’t have jurisdiction over a “routine parole denial.” His legal team took the case to the South Carolina Court of Appeals, protesting that the Department of Probation, Parole and Pardon Services allowed the board to present false information and blocked efforts to correct it. The court heard oral arguments in April and has not yet issued a decision.

With parole declining, the vast majority of people who are now released from South Carolina’s prisons are freed because they served the entirety of their sentence. In 2019, 16 percent of people released from prison were on parole. Last year, that figure was just 3 percent.

At the same time, state prisons are operating at close to capacity in the midst of continued staffing shortages, creating conditions of unrest that contributed to a 2018 uprising at Lee Correctional Institution that left seven people dead; from 2001 to 2019, South Carolina had the highest rate of prison homicide in the country.

Unlike many states, the South Carolina parole board operates separately from the corrections department. “They have no financial incentive to parole some of these people who clearly pose no danger to anyone,” Blume, the Cornell professor who has represented parole applicants, told Bolts. “The Department of Corrections would like these people to be released, because they have overcrowding problems and it doesn’t do them any good to continue to warehouse people who pose no danger and who have long served the retributive portion of their sentence.”

A report last year from the parole agency showed that the vast majority of people released on parole in South Carolina don’t pose a threat to public safety, with 83 percent of people on parole successfully completing their supervision period.

One of Douglas Jennings’ last clients was Jason Matthews, 55, who has been incarcerated since 1989 for the murder of Jerry Shelton, a local police chief who had been under state investigation for allegations of abusing his position. Matthews has long maintained that Shelton sexually assaulted his girlfriend and threatened them with a gun, spurring a gunfight. Though there was no evidence showing whether Matthews or his girlfriend fired the fatal shot, Matthews accepted a plea deal to avoid the death penalty. A jury acquitted his girlfriend after she took her case to trial. A federal judge in 1994 wrote a letter recommending that Matthews’ sentence be vacated because the case against him was so flimsy.

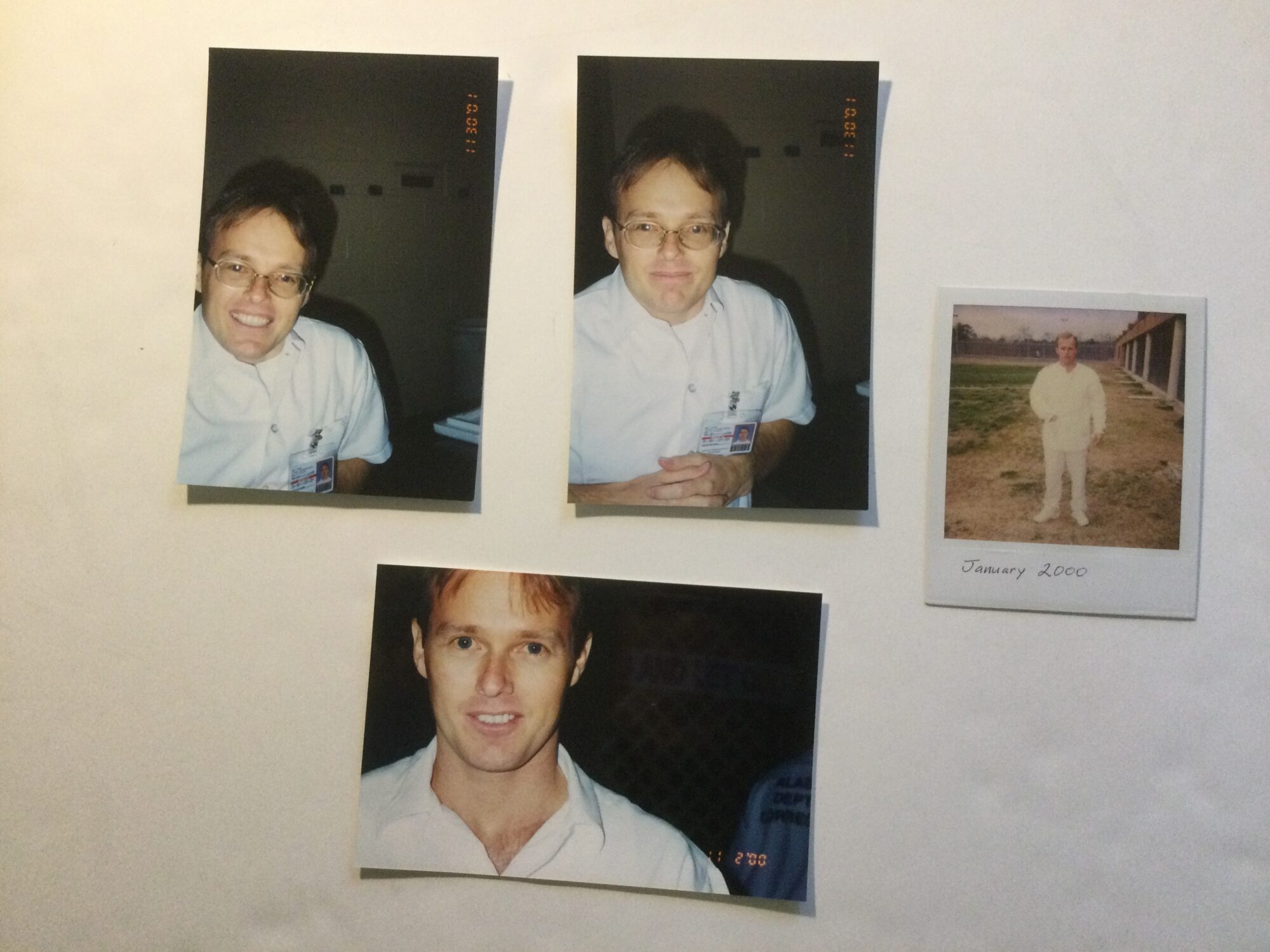

Like Blackwell, Matthews got clean during his time in prison. He has never committed a disciplinary infraction, regularly participated in prison programming, and amassed a long list of certificates for sewing, custodial services, and plumbing.

“I’m asking for the privilege of parole, to turn my life around, to be able to move forward in life, to where I can go forward, and do even greater good that I’ve done while I’ve been in SCDC,” Matthews told the board, according to a recording of the hearing obtained by Bolts. “I’ve been a model inmate for nearly 35 years. Now I want to be a model citizen, law abiding, surrounding myself with good people.”

If released, Matthews told the board that he planned to take care of his ailing father and work as a volunteer in his local prosecutor’s office helping people addicted to drugs. He also has a job cleaning building exteriors waiting for him if he gets out. State Senator Gerald Malloy spoke in support of Matthews’ release, telling the board, “I have not had a case that is more recommended for parole than this.”

Miro, the interim parole board member who has approved more applicants than any other member this year, asked Matthews whether he’d reached out to the victim’s family, and he responded by telling her about letters he’d written to them expressing his remorse.

During deliberations among the board, Miro explained that she supported parole for Matthews. “I am reminded of what I think I was charged to do when we came here,” she said.

Miro then felt she needed to further justify her decision to the other members.

“I don’t know that I feel good about doing this,” she added. “But I think that’s what I think I may have to do. I just needed you all to hear me say that.”

The board denied Matthews parole by a vote of 3–2.

Jennings called the decision “so damn disappointing.”

“It just speaks volumes,” he said. “If this guy can’t make it, I don’t see how anybody can.”