Louisiana Governor Flexes Power to Police New Orleans, Defying Local Preferences

Landry has used emergency powers to increase state police presence and sweep unhoused people in downtown New Orleans. Advocates worry the measures could become permanent.

| February 24, 2025

As millions tuned in to watch the Super Bowl in New Orleans this month, outside the Superdome in the central French Quarter, thousands of law enforcement officers patrolled the streets.

The heavy police presence was the result of an emergency declaration by Louisiana Governor Jeff Landry in the wake of the New Year’s Day truck attack that killed 14.

The executive order authorized Landry to bulk up the presence of Louisiana State Police (LSP) within the city of New Orleans, and to “compel the evacuation of all or part of the population,” using whatever route, mode of transport, and destination he chooses. With a signature, Landry gave himself the authority to “control the movement of persons” within a certain area, making sure to note that he might need to set up “emergency temporary housing” for unhoused people camped near the stadium.

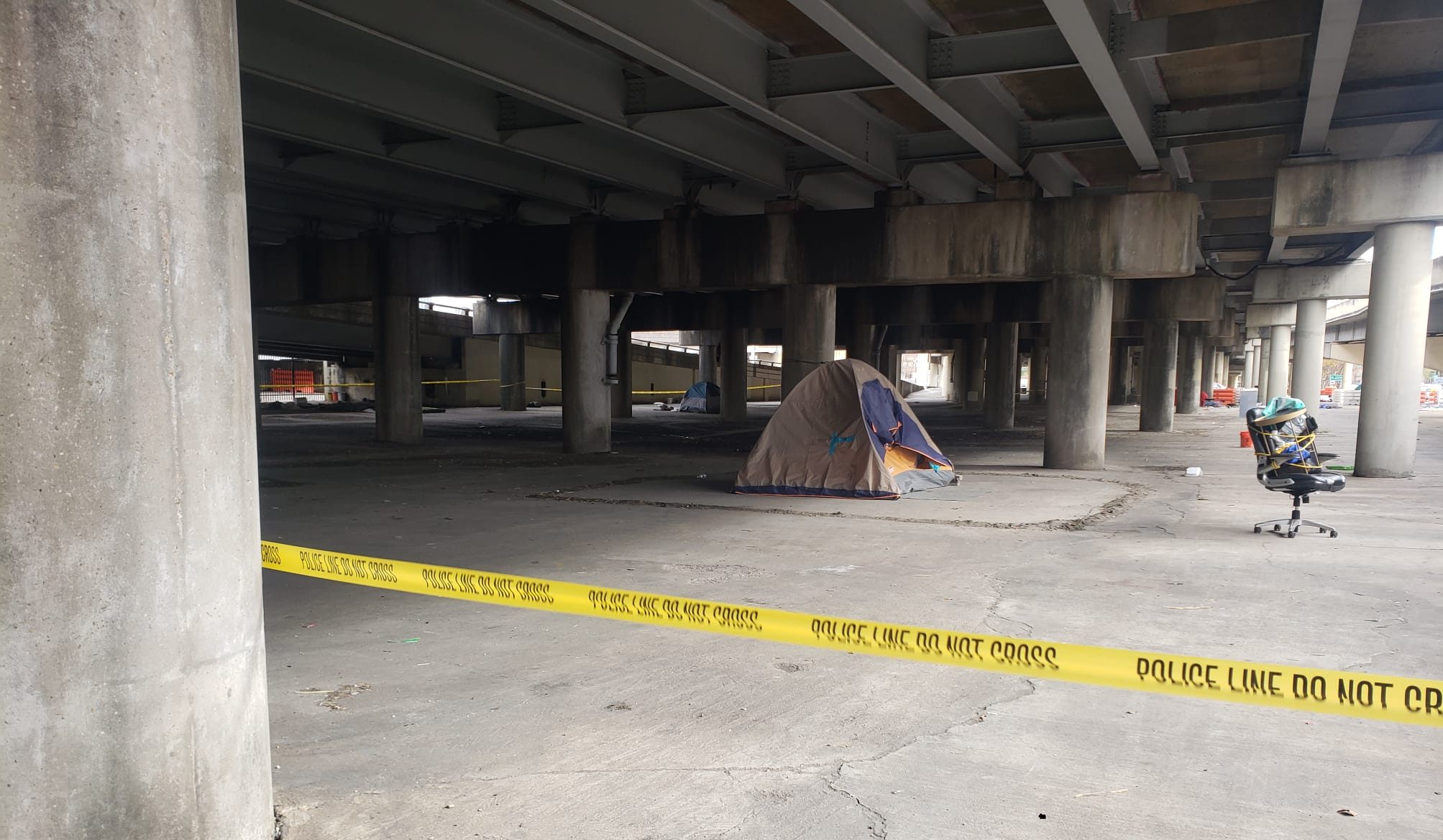

On January 15, Landry used those powers to send LSP officers out to forcibly displace unhoused residents of New Orleans’ downtown encampments, bussing over 100 people to a then-unheated warehouse miles away, under threat of arrest.

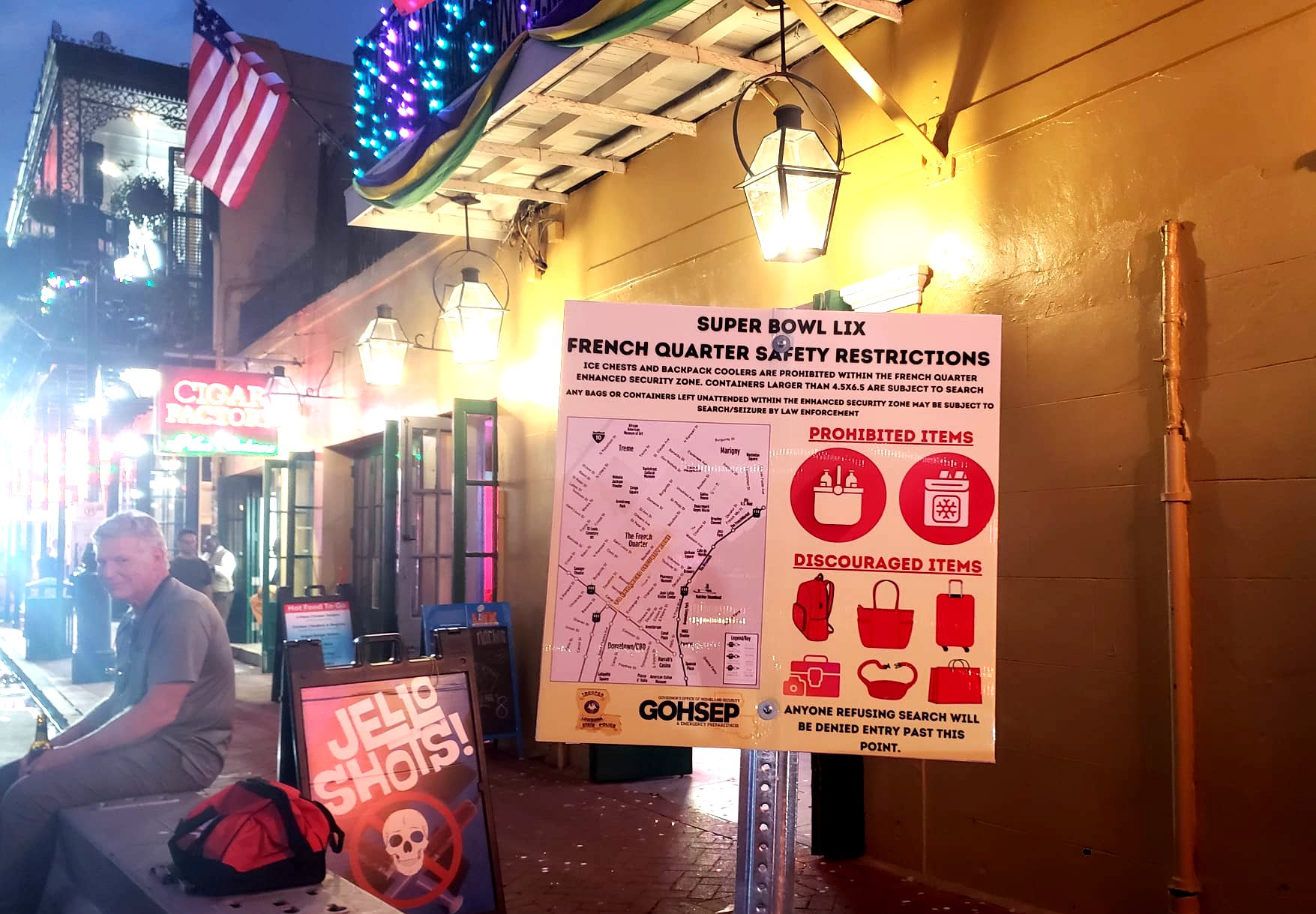

By the time the Super Bowl rolled around, the encampments were empty. Instead, swarms of officers from the LSP and other agencies roamed the Quarter, walking in clumps of five or six down Bourbon Street. At each intersection, knots of camo-clad Louisiana National Guard soldiers toted semi-automatic rifles, becoming a spectacle of their own: Some tourists posed near the officers for pictures, while others hurried past under the floodlights, clutching their cocktails. In Landry’s “Enhanced Security Zone” on Bourbon Street, ice coolers were banned, and fanny packs were discouraged—but concealed firearms were still permitted.

The emergency declaration is a temporary order in place until Feb. 27. The National Guard will soon go home. But local police watchdogs and criminal-legal reform advocates are increasingly concerned that LSP may be there to stay, enacting Landry’s vision of a tightly controlled New Orleans: one where business interests rule, the poor and unhoused are pushed out of sight, and local priorities are handily subverted by the state.

“This is definitely a signal of a new era of how New Orleans in particular is going to be policed,” warned Stella Cziment, the Independent Police Monitor (IPM) for New Orleans. LSP have patrolled New Orleans before, said Cziment. “However, I can’t stress enough now: This is not the same.”

When LSP began the sweeps of downtown, their mere presence made vulnerable people living outside fear the threat of arrest.

Erica Dudley and her husband lost their housing eight months ago, when they were evicted from the AirBnB where they were staying, around the same time she lost her job. Out of other options, they began camping in a tent under an overpass near the Mississippi River. Speaking the evening before the LSP began their scheduled January sweeps, she told Bolts that although she’s engaged in the months-long rehousing process through the city’s lead housing agency, repeated displacements by state police set back her efforts: She lost her wallet, ID, and social security card in an October sweep. She said the new round of sweeps would cause her to miss an appointment with the Social Security Administration to get a replacement card, scheduled for the following morning.

Dudley would’ve preferred to remain in her tent. But large notices near her camp appeared instructing people to move, and warning that those who refused to comply would face “enforcement actions or legal proceedings.” So she went to the state-run warehouse, dubbed the “Transitional Center,” saying that she “definitely would rather move than get sent to jail.”

Landry has justified the sweeps on the basis of public safety. But housing organizers point out there’s no connection between unhoused people and the New Year’s Day attack—in fact, unhoused people are far more likely to be the victim of a violent crime than the perpetrator.

“The governor is interested in the cash resources that New Orleans is able to generate for the state, especially when it comes to the Super Bowl,” said William Snowden, a law professor at Loyola University. “The interests are not really on behalf of providing safety for New Orleanians, but more concerned with…making sure the tourist industry continues to boom so they can continue to be a cash cow for the state.”

This latest move by Landry is a continuation of his efforts to target New Orleans in particular. As Louisiana Attorney General in 2022, he called for the state to withhold financing to pressure the city into enforcing the state’s punitive abortion laws. He’s talked about needing to punish the city, “to bring them to heel.”

Shortly after he became governor in January 2024, Landry announced plans for “Troop NOLA,” a contingent of up to 40 state troopers specifically dedicated to policing the city. Within months of becoming governor, he called a special legislative session dedicated to crime, where legislators approved millions in funding for Troop NOLA, which started patrolling the city in June 2024. Within weeks, their high-speed pursuits led to four car crashes in four days, some of which resulted in civilian injuries. The New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) have far more restrictive policies for vehicle pursuits due to a federal consent decree.

State police have been stationed in New Orleans before, after a 2014 mass shooting on Bourbon Street. That time, the LSP presence was temporary, and included a formal written agreement that gave the city some control over the state troopers. Then-AG Landry eventually disbanded his task force in the city in 2017, citing local opposition. But no formal agreement with LSP appears to exist this time.

The LSP presence is especially worrying for some criminal-legal experts because the agency has been under a civil rights investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice since 2022. The inquiry was sparked by video of a 2019 traffic stop, where LSP troopers shackled a Black man named Ronald Greene, turned off their body cameras, and beat him to death while Greene wailed, “I’m scared.”

The justice department issued a scathing report in January 2025, released just as Landry’s LSP-led encampment sweeps entered their second day, that found a statewide pattern of excessive force, including use of force without warning and on people who are not a threat—“even when they are in handcuffs.”

The report recommended, but did not mandate, several reform measures, including taking steps to minimize use of force and improve public accountability.

James Craig is the director of the Louisiana office of the MacArthur Justice Center. In 2016, the organization filed a civil rights suit against LSP command staff and troopers for excessive force and false detention. The suit stemmed from an incident in which a young Black man visiting New Orleans’ French Quarter with a group of students got separated from his party and was wrongly arrested by LSP officers. Craig says he now has serious concerns about “LSP’s deployment as a de facto occupying force in a Black-majority city.”

“This most recent intrusion by LSP and other state officials, countermanding the efforts by city government and community groups to address the issues of unhoused residents, is another example of the State’s disregard for local self-government,” Craig told Bolts.

Cziment, the New Orleans police monitor, also points out that her office only has jurisdiction over city police, not state troopers. The police monitor’s office can make formal recommendations for the NOPD, and facilitates public transparency.

But “there is no formalized accountability process for LSP outside LSP,” said Cziment. There is nobody to take reports or suggest reforms, nor formal reporting requirements, nor obligation to public transparency.

Observers in New Orleans warn that Landry is using the LSP to enact his vision for housing and police policy in the city—which so far has been a strategy of displacing the unhoused while defunding housing and support services.

In his approval of the state budget last June, the governor vetoed $1 million for a homelessness shelter in Lafayette, and took funding from a housing project for formerly incarcerated people in New Orleans. Last March, he pushed through an appropriations bill, of which the vast majority—$22 million—went to LSP, including its Troop NOLA arm.

He first directed state troopers to sweep unhoused people from downtown New Orleans in October 2024, ahead of a Taylor Swift concert, over the objections of city leaders. His attempts to move people into a single encampment were temporarily halted by a court order. Its reversal by the state supreme court in January allowed for the most recent sweeps.

But Snowden sees this as a slippery slope: The more Landry wields police to exert control over one issue, like homelessness, the more control he wields over the city’s entire criminal-legal process.

“The reason I think it’s going to be longer than just the Super Bowl, is this is another opportunity for the state government to have its hand in influencing what prosecution looks like in New Orleans,” said Snowden.

The current agreement between the local district attorney and the state attorney general, explained Snowden, is that arrests that are facilitated by the Louisiana State Troopers will be prosecuted by the AG’s office. “That gives them a continued interest to maintain the presence of Louisiana State Police in New Orleans, so they can continue to prosecute cases,” Snowden said.

The current director of the AG’s criminal division is Leon Cannizzaro, the notorious former DA of Orleans Parish who was successfully sued by the ACLU, MacArthur Center, and other rights groups for issuing fake subpoenas and coercing and jailing witnesses. Advocates worry that referring prosecutions to his office will lead to extreme penalties, like charging juveniles as adults, and using Louisiana’s habitual offender statute that allows for very harsh sentencing—a statute the Orleans DA had previously vowed not to use.

“At this point, roughly 10% of our cases are prosecuted by the Attorney General,” said Lindsey Hortenstine, communications director for the Orleans Public Defenders. “In seemingly all cases that are multiple bill eligible, the Attorney General’s office either institutes the multiple bill enhancement or threatens use,” often resulting in guilty pleas. “This practice has a significant chilling effect on people exercising their right to trial.”

The New Orleans DA likewise has signed a cooperative agreement with the state AG, allowing the state, not the local DA, to oversee and respond to any LSP misbehavior—including NOPD activity that has any LSP involvement.

The impunity enjoyed by LSP was further codified by a recent ruling from the Louisiana Supreme Court, which affirmed that LSP cannot be restricted by local or municipal ordinance.

Neither Snowden nor the attorneys involved in the Louisiana Supreme Court case were aware of another example of State Police having such court-affirmed powers to supersede municipal priorities.

Snowden warned that with the rolling back of reforms, “ten, fifteen years from now, we’re going to see our incarceration population be out of control.” He added that the return to antiquated policies is demonstrably ineffective, and “if incarceration did provide public safety, Louisiana would be one of the safest places in the country, because we’ve had the highest incarceration rate for decades. But we’re not the safest.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.