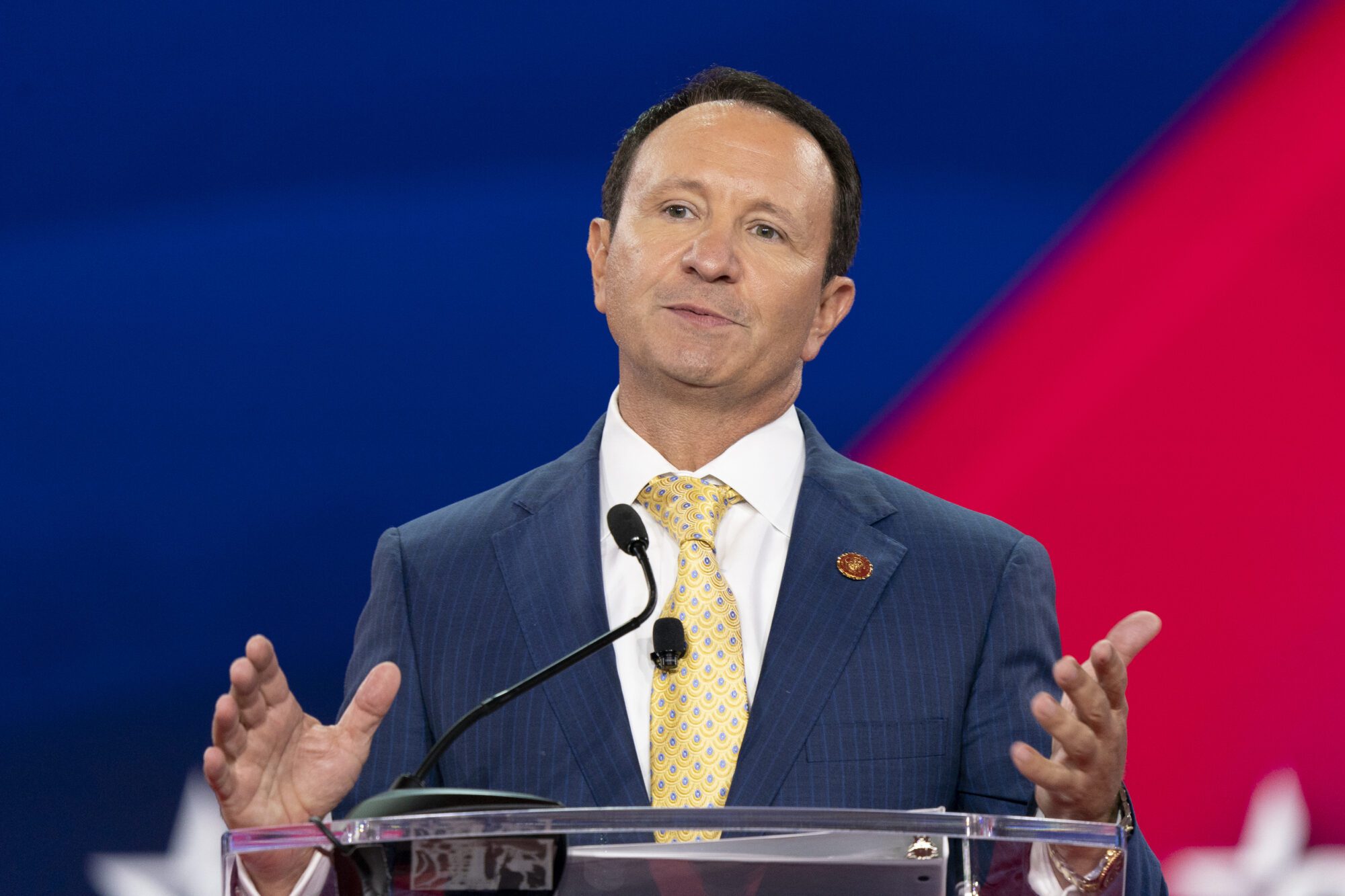

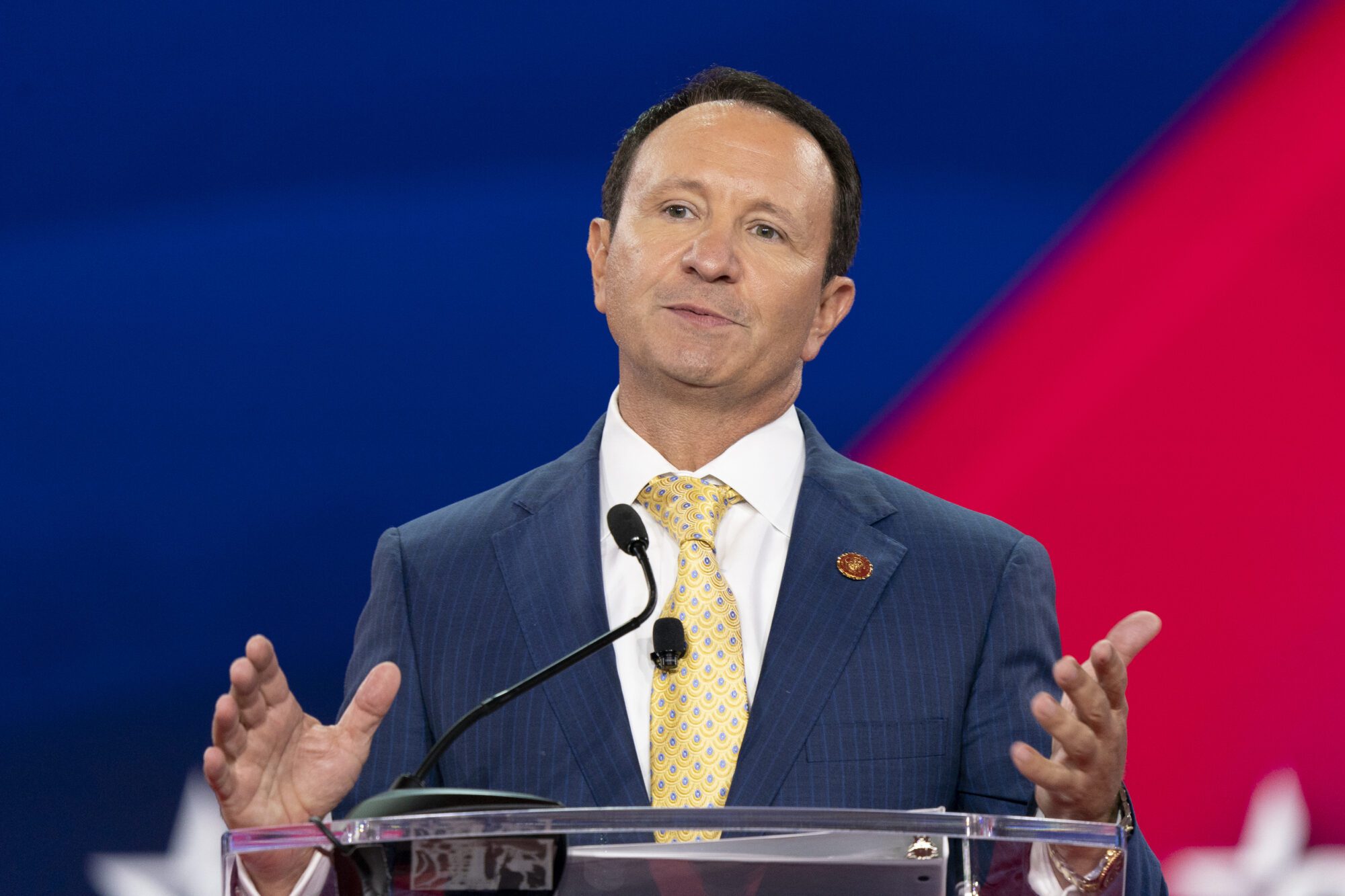

Jeff Landry’s Bid for Louisiana Governor Has Been a Crusade Against Its Cities

As attorney general, Landry has relentlessly targeted New Orleans and other largely Black cities, and shielded its police from reforms. Now he’s bringing that message to his campaign.

Piper French | August 31, 2023

Jeff Landry faces 15 opponents in Louisiana’s gubernatorial race this fall, but at times, it seems like the Republican attorney general is really running against the state’s Democratic, majority-Black major cities.

In his announcement video, the candidate blasted Louisiana’s “incompetent mayors and woke District Attorneys” for what he sees as their role in allowing crime to proliferate. He doubled down in a series of campaign videos that called out the DAs of Caddo, East Baton Rouge, and Orleans for the three parishes’ crime rates, highlighting images of the two Black prosecutors but omitting any footage of East Baton Rouge DA Hillar Moore, who is white. “When DAs fail to prosecute—when judges fail to act – when police are handcuffed instead of the criminals—enough is enough,” he announces.

In 2022, he assisted a Republican lawmaker in unveiling a bill, House Bill 321, that would have made public the criminal records of young people between ages 13 and 18 who are accused of a violent crime—but only in Caddo, East Baton Rouge, and Orleans, all parishes with some of the highest concentrations of Black residents in the state. Landry made news appearances advocating for the bill and spoke at the press conference announcing it, later using portions of his speech for campaign ads attacking those three parishes’ DAs.

Bruce Reilly, a formerly incarcerated criminal justice reform advocate who testified against the bill at the Capitol, sat behind Landry as he spoke in favor of HB321. “If you think this is a good thing, why wouldn’t you do it in your own town?” he wondered.

It’s not uncommon for Republican candidates to blame Democrats for crime rates in the cities they control as a way of establishing conservative bona fides. But Landry’s campaign rhetoric isn’t just bluster. During his seven-plus years as attorney general, he has used the power of his office in standard, unorthodox, and at times highly controversial ways to single out New Orleans and the state’s other big cities.

Landry’s actions have ranged from creating a short-lived anti-crime task force that made arrests in New Orleans without clear jurisdiction to to spearheading punitive legislation that only applied to Louisiana’s three major cities. He also tried to strike down a federal consent decree ensuring a majority-Black state supreme court district in Orleans Parish. And he even recently tried to withhold flood protection funds after city officials suggested they wouldn’t prioritize enforcing abortion crimes.

Landry, whose campaign did not respond to interview requests from Bolts, will face off against his actual opponents in the primary on Oct. 14. If no one candidate gets more than 50 percent of the vote, the top two, regardless of party, will compete in a runoff on Nov. 18. The incumbent, Democrat John Bel Edwards, cannot seek re-election due to term limits, and Landry has so far been the front-runner in public polling.

A win by Landry would return unified control of Louisiana’s government to the GOP. But it would also elevate and empower a man who has tirelessly sought to undermine the political power of the state’s major cities and shield law enforcement from local and federal reform efforts.

“The place is being run like a third world-country,” the attorney general said of New Orleans during an appearance on Tucker Carlson’s show last October. “Why doesn’t the state just take it over?” Carlson asks. “It’s a great question,” Landry responded. “In Louisiana, we have one of the most powerful executive departments in the country. The governor is extremely powerful. He has the ability to bend that city to his will, and he [Edwards] just doesn’t.”

“But we will.”

After an early stint as both a police officer and sheriff’s deputy, followed by law school, Landry was elected to Congress in 2010 as part of the ascendant Tea Party, the proto-MAGA movement that crusaded against taxation and federal government overreach. During his lone term representing Louisiana at the national level, Landry posed with a chainsaw in his office, meant to symbolize his willingness to make sawdust of the national budget. His time in Congress would be short lived—ironically, his congressional seat was eliminated during redistricting after New Orleanians left the city in droves in the wake of Hurricane Katrina—but he brought the chainsaw approach to his new role as attorney general, especially when it came to opposing Obama-era federal policy and executive orders.

Since he took office in January 2016, Landry has waged a rhetorical war on crime in New Orleans filled with racist dog whistles implying that the majority-Black city is lawless and out of control. “He definitely appeals to race,” said Bruce Reilly, the Deputy Director of Voice of The Experienced (VOTE), a group of formerly incarcerated Louisianans and their allies that advocates for criminal legal reform. “You pile on the Black mayor, the Black DA, the Black sheriff, right—it’s known as a Black city.”

“I think it’s obvious,” Caddo Parish DA James Stewart, who is Black, said in an interview about the campaign videos in which he and New Orleans DA Jason Williams are depicted but their white counterpart in East Baton Rouge is not.

Landry’s belief that New Orleans and other major cities are being poorly run is inextricably tied to his desire to police them more heavily and without restraint. In Landry’s interview with Carlson last October, he made it clear what he believes to be the solution to New Orleans’s woes. “That’s the way you start to take back control of these cities: by instituting state and local control—in law enforcement,” the attorney general said. He has also argued that New Orleans police should be allowed to use stop-and-frisk practices, which a decade-old consent decree, which grants federal oversight of the city’s police department in order to institute reforms, prohibits.

“I think he genuinely is completely unwilling to entertain the idea that there are solutions to crises that we have in our state that are not driven by criminalization,” Mercedes Montagnes, a local civil rights lawyer, said of Landry.

In July 2016, citing rising crime rates in the Big Easy, Landry created a Violent Crimes Task Force consisting of five state agents from the Louisiana State Police Bureau of Investigation who would patrol and make arrests within New Orleans city limits. His announcement was met with statements of support from some local officials, but within months, the New Orleans chief of police had signaled to Landry that his office had no authority to engage in law enforcement in the city, and a spokesman chided Landry for using the department, and the city itself, as a “prop in political agendas.”

Landry ultimately disbanded his task force amidst criticism from local officials and a federal judge, who said she believed that Landry lacked the authority to direct agents to make arrests in New Orleans and stressed the importance of police operating only where they have the authority to do so in order to ensure that arrests were valid. Its actual impact was far thinner than the controversy it fomented: In nearly a year of operations, the task force had made only 16 documented arrests, leading to at least one case where a public defender argued the arrest was illegal (it was upheld).

Landry has also heaped scorn on the consent decree governing the New Orleans Police Department, consistently implying that it is a misuse of federal authority (he recently called it a “pernicious threat to federalism”) and said that it “handcuffs cops instead of criminals,” a pet phrase of his.

The decree, which Landry also likes to refer to as an example of what he calls “hug a thug” policies popular with Democrats, was put into place in 2013 after a U.S.Department of Justice investigation—itself sparked by an incident just six days after Hurricane Katrina in which a group of New Orleans police officers in street clothes toting AK-47s shot at a Black family and their friend as they were walking to the grocery store. Two of them were killed, including a 17-year-old; four others were severely wounded, including one woman whose arm later had to be amputated. The department then tried to cover up the shooting. Federal investigators found “patterns of misconduct that violate the Constitution and federal law,” which they stressed went far beyond the incident itself.

The subtext to Landry’s crusade is not merely opposition to federal power or a desire to assert state-wide control—it’s a distaste for any checks on police power. In 2017, he penned an editorial heralding the news that the end of the consent decree was near (it wasn’t). “As expected when police priorities are subject to the approval of activist judges and Washington lawyers, the community suffers and criminals benefit,” the AG wrote.

In recent years, Landry’s campaign against the consent decree has aligned with the efforts of New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell, otherwise a frequent sparring partner of Landry’s, to put an end to the decree. (Still, as of April, more than half of the city council opposed the mayor’s stance as of April and said the consent decree should stay.)

But Montagnes, the civil rights lawyer, stressed that Landry’s actions were more about politics than his assessment of how far the New Orleans police department has progressed since the implementation of the consent decree. “[Jeff Landry] is not talking to people in New Orleans,” Montagnes said. “He’s not holding community meetings. This is just based on his unilateral position that we should not trust the federal government, and we should get them out of our business.”

Landry has used his office to retaliate against city leaders who disagree with him on abortion criminalization and immigration enforcement, at times withholding key funding and jeopardizing important city functions with his political gamesmanship.

In 2016, after New Orleans police adopted a policy preventing officers from inquiring about people’s immigration status, Landry helped craft a bill that would prevent so-called sanctuary cities from accessing state bond money for construction projects. The bill would have also granted him, as attorney general, sole authority to define what a “sanctuary city” actually was—under his definition, New Orleans was the only municipality that qualified.

Some lawmakers worried that the bill would give Landry too much power, and could place the city in conflict with its own consent decree. New Orleans, meanwhile, maintained that its police force’s anti-discrimination policies, including its best practices around immigration status, came at the behest of the federal government itself. Versions of the bill died in 2016, 2017 and 2023.

In late 2022, Landry used his position on the Louisiana State Bond Commission to try and hold up $39 million dollars in flood prevention funding for New Orleans after the city council passed a non-binding resolution related to Louisiana’s harsh new abortion law, which lacks rape or incest exceptions. The city resolution requested that police and prosecutors make investigation and enforcement of the law “the lowest priority.”

Landry responded by urging the commission to “use the tools at our disposal to bring them to heel.” Initially, his fellow commissioners seemed to agree, voting twice to stop the funding from moving forward. But their support crumbled, culminating in a tense, at times openly hostile meeting in September in which the board ultimately voted to approve the funding. “To use this commission as a political maneuver is not our position—shouldn’t be our position, I feel,” said Lieutenant Governor Billy Nungesser, claiming he hadn’t realized how the representative he had sent to previous meetings had voted.

“We’re talking about someone whose job it is to sit on the bond commission withholding vital infrastructure funds to punish any democratically elected local government,” said Monika Gerhart, an energy consultant and the former director of intergovernmental relations for the city of New Orleans. Gerhart is currently consulting on policy for Shawn Wilson, one of Landry’s chief opponents.

Gerhart believes that Landry’s ultimate goal wasn’t even to punish New Orleans, but rather to force his fellow commissioners, several of whom were also considering a run for governor, to vote to signal their anti-abortion bona fides, inevitably angering a large municipality whose residents would soon go to the polls to choose whether to elect them as governor. He has since announced that he will not run, but at the time, Nungesser was considered Landry’s most viable Republican opponent in the gubernatorial race; another commissioner, State Treasurer John Schroeder, is a more centrist Republican whom Gerhart believes will likely seek to court New Orleans Voters, especially if the race were to come down to a run-off between him and Landry.

“It was a completely manufactured crisis,” she added. “I think it’s a really dangerous way to prioritize politics over governance.”

Landry is, of course, running to be governor of the entire state. But Reilly believes Landry sees it as more advantageous to scapegoat New Orleans in order to rally his base than he does to seek out its residents’ votes. In Louisiana, he said, “you can win an election on all rural votes. You can win an election on all white votes.”

And so far, those are the very voters Landry seems to be courting with his campaign. He aligned himself with Trump early on and received his endorsement, and he has woven his critiques of New Orleans into a larger “tough on crime” platform. His main Democratic opponent, Wilson, meanwhile, is charting a moderate approach, emphasizing his statewide leadership experience and credentials; his slogan is “We need leaders who will build bridges, not burn them.”

If Landry wins control of Louisiana’s executive branch, he would have the power to staff many of Louisiana’s more than 500 boards and commissions, including a number with direct power over the state’s criminal legal system, such as the Committee on Parole, the State Police Commission, the Police Officer Standards and Training (POST) council, and the Louisiana Sentencing Commission. Landry would also have ultimate say over the state’s budget;. the office’s line-item-veto power means that Landry would have the ability to, with the stroke of a pen, edit the state’s budget in order to divert resources away from New Orleans and other cities when they adopt policies he doesn’t like.

Critics of Laundry’s who spoke to Bolts fear he would go even further in inserting the state into New Orleans politics on issues like crime, homelessness, and social and cultural issues—much like Governor Ron DeSantis has done in Florida.

“There’s this incredibly complicated relationship between the remainder of our state and New Orleans,” said Montagnes. New Orleans is the center of business and tourism in Louisiana, she said, “but I think it becomes a bogeyman on cultural, social issues, and I think that Jeff Landry is really particularly interested in dividing people of Louisiana based along those issues. And so we’d be an easy target.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Louisiana Votes

Bolts is closely covering the ramifications of Louisiana’s 2023 elections for voting rights and criminal justice.