In North Carolina, Juvenile Lifers See a Pathway to Freedom

After the state’s previous governor granted clemency to people sentenced to life in prison as minors, others with juvenile life sentences are hoping the new administration also believes in second chances.

| April 15, 2025

Some of Joseph Jones’ earliest memories are of visiting his father in prison. Then abandonment, when his parents left him in North Carolina and moved to New Jersey after Jones’ father was released.

That’s how Jones wound up living in abject poverty in Burlington with his young aunt and uncle, who led him down the wrong path instead of teaching him how to pop a wheelie on a bike or toss a football. Jones says that he was acting at the direction of his 16-year-old uncle and his uncle’s girlfriend in 1998 when he took part in the rape and murder of a 10-year-old girl who lived in their neighborhood. Jones, who was 13 at the time, was later convicted and sentenced to spend the rest of his life in prison without the possibility of ever being released on parole.

Jones remembers being jumped by six other kids his first day at North Carolina’s High Rise youth prison, a towering 16-story building in between Asheville and Charlotte that the state would tear down decades later. It was there in the tower that other kids gave Jones a nickname, Baby J, that has outlived his nearly three decades of incarceration.

Jones, now 40, still looks almost frozen in adolescence with a slim, mocha-colored face that’s hairless except for a thin mustache and black tuft curling beneath his chin. When I interviewed him inside Neuse Correctional Institution, a medium-custody adult prison in Goldsboro, Jones recalled his struggle for survival in the High Rise. “I fought for my life in there,” he said. “We all had to. And in some ways, I’m still fighting.”

Jones says the crime that landed him there as a child still dominates his thoughts. “I can’t explain how much I think about what happened that day,” Jones said. “Nothing I say or do now can change it. So I focus on being the best person I can be, but I don’t know if I’ll ever be able to overcome something I did as a stupid little kid.”

Jones is one of nearly 200 people sentenced to life without parole and other very lengthy prison terms as children who filed petitions for clemency with a board that then-North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper established in 2021 to review such cases. Of the 191 petitions filed under that initiative, Cooper granted the release of just 12 people before he left office in December 2024. Cooper, a Democrat, also made two petitioners who had already served 20 years in prison eligible for parole, while denying relief for 88 others, according to data from the governor’s office. Fourteen other petitioners finished their sentences and were released before the governor could make a decision on their cases.

Jones is one of 75 petitioners who did not get a decision from Cooper, putting his fate in the hands of Josh Stein, a Democrat who replaced Cooper as governor in January. Advocates for sentencing reform are now asking Stein to act on cases like Jones’ that Cooper left in limbo, and to restart the board to keep hearing new petitions from people sentenced to long prison terms as children.

A spokesperson for Stein said his office “is reviewing clemency-related policies and procedures under the new administration” and “continues to review all petitions received.”

Cooper’s Juvenile Sentence Review Board (JSRB) was just one example of actions that states have taken in the wake of court rulings against extreme sentences for children in recent decades. A series of U.S. Supreme Court decisions since 2005 have affirmed that “children are constitutionally different from adults in their levels of culpability” and thus deserve “meaningful opportunity to obtain release,” ruling that the death penalty and mandatory sentences of life without parole for minors violate the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment.

A wave of states have since passed legislation to entirely abolish life without parole for people under 18. These reforms have granted thousands of people who are already incarcerated a chance to apply for release, typically only once they’ve spent decades in prison. As of 2025, 28 states, plus D.C., have ended juvenile life without parole sentences.

In an effort to comply with court rulings against extreme juvenile sentences, North Carolina lawmakers passed legislation in 2012 allowing judges to revisit the punishment of people who’d been sentenced to life without parole automatically and consider alternatives. In 2022, the North Carolina supreme court ruled that sentences of more than 40 years are functionally equivalent to life without parole when it comes to these new protections—which effectively set a new 40-year limit before someone convicted as a child can become eligible for release unless a judge has deemed them “irredeemable” or “incorrigible.”

Cooper’s executive order in 2021 outlined a path for people sentenced to life in prison as juveniles to secure release through clemency, rather than through parole applications.

One person who benefited is Sethy Seam, who got a second chance because of Cooper and the JSRB. Seam, a husky man of Cambodian descent, went to prison at 16 for his participation in a 1997 convenience store robbery that ended in the shooting death of the store’s owner. Seam had rejected an 18-year plea deal from prosecutors and was sentenced to life without parole after being convicted at trial. His co-defendant, the shooter, accepted a deal and was released in 2022, two years before Seam was granted clemency by Cooper.

Seam had previously filed for resentencing and a court changed his sentence to life with the possibility of parole in 2017. But Seam also battled with drug addiction in prison, which he says effectively blocked him from actually getting parole.

“My mom kept it real with me,” Seam told me during our phone interview. “She wanted me home, and I was messing up. By the grace of God I stopped using drugs.”

Seam went on to earn his GED and completed vocational programs to better himself before filing his petition for clemency with Cooper’s review board for juvenile sentences. Cooper included him in his final series of commutations in December before his departure from the governor’s office, which marked the official end of the JSRB. Seam walked out of prison in January, after 27 years behind bars.

“I’m thankful for the chance I got,” Seam said. “But I wish Governor Cooper had helped more people. A lot of kids had hard lives. They did 25 years in prison, and now they’re a whole lot different. They need hope, too.”

North Carolina’s Juvenile Sentence Review Board sprang from a broader attempt to address racial inequities in the criminal legal system in 2020, following George Floyd’s murder by police and the protests it sparked across the country.

Cooper issued an executive order early that June establishing the North Carolina Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice, giving it a mission “to develop and help implement solutions that will eliminate disparate outcomes in the criminal justice system for communities of color.”

State Representative Marcia Morey, whom Cooper appointed to the task force, had worked as a prosecutor and judge overseeing juvenile cases before being elected to represent Durham in the state House in 2017. Morey told me during a phone interview how she encountered several young people like Jones during her time on the bench who were in vulnerable situations before committing a crime.

“Many were afflicted by poverty, abuse,” Morey said. “Maybe they were hungry or dropped out of school. There were so many issues we could have addressed. We could have prevented some of these crimes before they happened.”

Early in her work on the governor’s task force in the summer of 2020, Morey wanted to know more about people in adult prisons who were still serving sentences that they received as children. So she turned to Ben Finholt, director of the Just Sentencing Project at the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke University’s law school, who delivered some sobering figures: More than one thousand adult prisoners in the state had been sentenced as kids, around 83 percent of them people of color.

While new sentences of juvenile life without parole had markedly declined in the state because of court rulings on the issue, Finholt informed Morey that around 100 people were still in adult prisons on life without parole sentences for crimes they committed as children. About 100 others were still in prison serving terms of 30 or more for crimes they committed as minors.

Morey’s task force issued a report at the end of 2020 cataloging inequities across the system, including the disparities in extreme sentences for children from minority backgrounds. The report also contained a long list of recommendations, including that lawmakers eliminate life without parole sentences for children and that Cooper create a board within the governor’s office to review such cases for consideration of clemency.

Finholt drafted the executive order that Cooper eventually issued and signed in April 2021 creating the JSRB. The order directed the governor’s four appointees on that board to hear petitions from anyone in North Carolina’s adult prison system for a crime they committed as a minor who had already served at least 15 or 20 years behind bars, depending on their sentence. Cooper’s order also outlined several factors the board should consider in deciding who to recommend, such as rehabilitation and maturity behind bars, whether they had adult co-defendants or accomplices, and whether someone’s race influenced their trial or sentencing.

After Cooper created the JSRB, Finholt quickly got to work mailing letters to more than 270 people in prison who he already knew were now eligible for clemency review. Nearly all of them responded asking for help filing petitions because they couldn’t afford an attorney. Finholt says the Wilson center wound up finding pro bono lawyers for 111 of the 191 people who filed petitions with Cooper’s JSRB.

Finholt, a former high school teacher, says he holds a special place in his heart for young people who end up in the criminal legal system. Research shows how young people who commit violence have often endured their own childhood trauma. One 2012 survey by the Sentencing Project of people sentenced to life in prison as juveniles found that 79 percent witnessed violence in their homes regularly and 47 percent had been physically abused.

“People who commit a sex offense or robbery as a child aren’t living happy lives,” Finholt told me during a phone interview.

The executive order that Finholt drafted for the governor’s office points to research in neuroscience and psychology showing how developmental differences between juvenile and adult minds give young people less control over their actions, making them less culpable for their conduct and better candidates for rehabilitation.

“No child is in control of their life, and they shouldn’t be,” Finholt said. “We don’t trust them to drink until 21. They can’t join the Army until 18. They can’t even get a job at 14 without a work permit. But if they commit a crime, we have laws that send them to prison for life—laws passed by lawmakers who wouldn’t treat their own kids the same way.”

After creating the JSRB, Cooper appointed Morey to chair it. “Every case was unique,” she told me during our phone call. Morey said she couldn’t comment on individual petitions but stressed how young some people were when sentenced to live the rest of their lives behind bars.

The 12 people Cooper ultimately released from prison after their cases were reviewed by the JSRB were part of a broader focus on clemency in the final stretch of Cooper’s tenure. During his eight years in office, Cooper issued 34 pardons and 43 commutations, including commuting 15 death sentences to life without parole in December, on his final day in office.

That’s a marked increase from other 21st-century governors: Collectively, Cooper’s three predecessors granted clemency or commutations to only 32 people over a 16-year period.

The expansion of clemency under Cooper has drawn backlash from Republican lawmakers, who filed a bill in February proposing that all reprieves, commutations and pardons given by the governor be approved by majorities in both chambers of North Carolina’s legislature—a change that would also require a popular vote to amend the state’s constitution. The state supreme court, which has flipped to GOP control since expanding protections against juvenile life sentences in 2022, has started to backtrack on those new limits in rulings this year.

While Finholt and Morey praised the increases in clemency under Cooper, both said they had hoped the JSRB’s work would lead to even more releases of people sentenced as children. While Morey said its exact recommendations to the governor are confidential, she also told me that the board had recommended that Cooper consider dozens of petitions for possible clemency.

“But we didn’t have the final say,” Morey said. “After our review, the governor’s clemency office contacted victims and their families, district attorneys, law enforcement, to see how they felt about a candidate. We didn’t do that.”

Finholt says he’s now pushing for Stein to decide on the dozens of petitions that Cooper left pending. Stein, in his former role as state attorney general, participated in the former governor’s task force that led to the juvenile review board.

Morey says she also hopes that Stein will reinstate the board, which officially dissolved on Cooper’s last day in office, to hear any cases that may have fallen through the cracks.

“I think it’s necessary,” Morey said during our interview. “The JSRB addresses a unique set of individuals, all who were minors. Those call for special consideration.”

April Barber Scales also grew up seeing the inside of prison, with both of her parents incarcerated. She was living with her adopted grandparents when she became pregnant at 15, by a man twice her age. Barber Scales, who is Black and Native American, says that after her grandparents tried to make her get an abortion, the man convinced her to set their house on fire.

Barber Scales pleaded guilty to two counts of first-degree murder after the blaze killed the couple, and a judge gave her two stacked sentences of life without parole. In her memoir “Fenced In: Fighting for Freedom,” Barber Scales recounts being shackled while giving birth to her son as an incarcerated teen, and then being forced to hand off her newborn to be raised by someone else. She says that trauma initially put her down the wrong path in prison before she managed to turn her life around by pursuing education however she could.

In 2022, Cooper decided that Barber Scales deserved a second chance, granting her clemency and release after the JSRB reviewed her case. Barber Scales had spent 31 years in prison. Without Cooper’s action, she likely would have been required to spend about another decade behind bars before becoming eligible for parole—and even then, parole was never a guaranteed path out.

Since her release three years ago, Barber Scales has completed an associate’s degree and is now finishing a bachelor’s in criminal justice. In addition to her studies and work as a home healthcare specialist and personal trainer, she volunteers as a peer support counselor for people in jail who are struggling with addiction. In her spare time, she also co-hosts the podcast The 98% – Life After Prison.

“Part of my volunteer work is helping people change while incarcerated,” Barber Scales told me during our phone interview. “I hope that reduces the chance for them causing future harm.”

Barber Scales is now thriving as a formerly incarcerated lifer, which tracks with research showing how few people previously sentenced to life for violence ever return to prison after release. Barber Scales says that she hopes more women she was incarcerated with get a second chance like her.

“More women serving long sentences should have the opportunity for freedom,” she told me. “I earned my second chance. I’ll never go back, and they could be just as successful, too.”

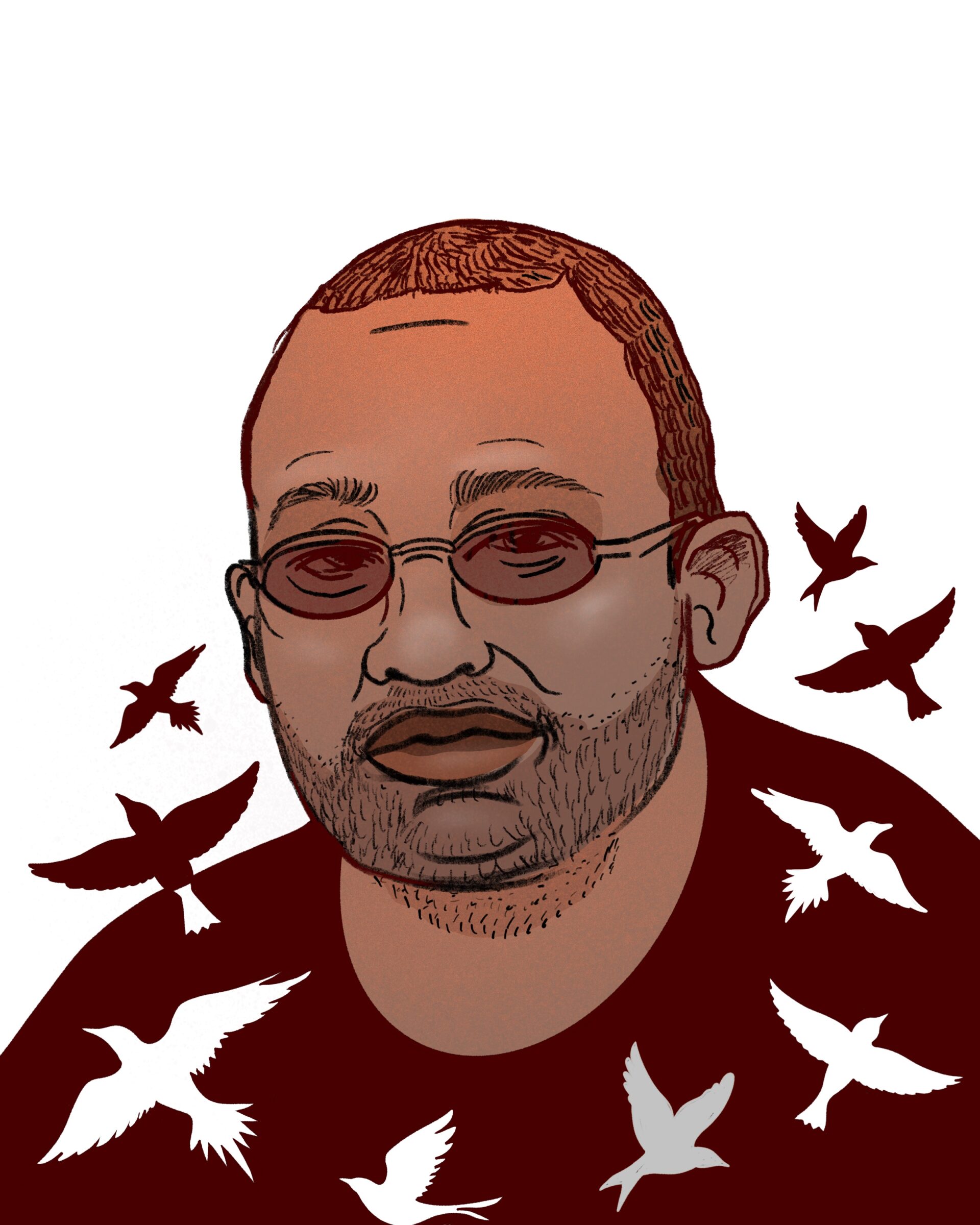

Leo Swain, who was sentenced to life without parole for a murder he committed at 16, says he struggled with addiction as a young person in prison. “When I came in, I had never used drugs,” Swain, now 42, said as we sat together and talked in a noisy dayroom at Neuse Correctional, where we’re both incarcerated. “I started because I needed an escape from thinking about never getting out of prison.”

Despite his past challenges, Swain, who is Black, has completed a plethora of classes to try and better himself during his quarter century of incarceration and feels confident that he’s ready for release. His petition for clemency to the JSRB was one of the 75 cases left pending when Cooper left office. He’s anxious to hear from the new Stein administration, saying he’s already been denied parole once after being resentenced to life with the possibility of parole in 2018.

“The longer they wait to let me out, the harder it’ll be for me to survive out there,” Swain told me. “I’ll be retirement age soon with no plan for the future. I don’t have much time left.”

Robert Johnson, a criminology professor at American University who has served as an expert in several cases where juvenile lifers sought resentencing, says it’s to be expected for people sentenced to lengthy terms as minors to exhibit behavioral problems during their incarceration. In an academic paper he published in 2020, Johnson explained how pressures associated with confinement are especially magnified for juvenile lifers, “because of their age and corresponding developmental stage,” which promote “feelings of anxiety, powerlessness, and rage.”

“People who grow up in the face of such adversity are extremely resilient,” Johnson told me over the phone. “It’s very difficult to mature in prison. But when people blossom in prison, they should be able to get out, so they can blossom in the free world.”

Jhalmar Medina says he has tried to learn and grow in prison, earning a GED and completing several vocational programs since he was sent there for a 2003 shooting that killed one person and injured another. Medina, who was born in El Salvador and was 16 at the time of the shooting, was sentenced to life without parole as well as given another 15-to-20-year sentence to be served concurrently—meaning he could have to serve 40 years to become parole eligible under the current guidance by the state supreme court. Medina, who is now 38, would be 56 years old by then.

Medina didn’t file for clemency with the JSRB under Cooper because his attorney and brother told him that his disciplinary record in prison was too lengthy to be considered.

“To survive in here at a young age, I had to give myself to prison,” Medina told me when spoke in a secluded corner of a cellblock at Neuse Correctional. “Average people don’t understand that. You learn to do prison or you get swallowed by prison. After I was denied all my appeals, there was no hope. At 17, I knew that I was going to die in prison. So I lived that way.”

Inside, we all call Medina “Dreamer” because of the nocturnal patterns he now follows, sleeping in his bunk during the day but awake all night while the rest of us are asleep, when Medina says the prison becomes peaceful. He now says he plans to file a petition for clemency with Stein’s office if the governor brings back the JSRB.

“I can’t change how I felt as a kid in prison,” Medina said. “But I’m building a better future. Maybe that counts for something.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.