Red State AGs Keep Trying to Kill Ballot Measures by a Thousand Cuts

Organizers say state officials have stretched their powers by stonewalling proposed ballot measures on abortion, voting rights, and government transparency.

| February 29, 2024

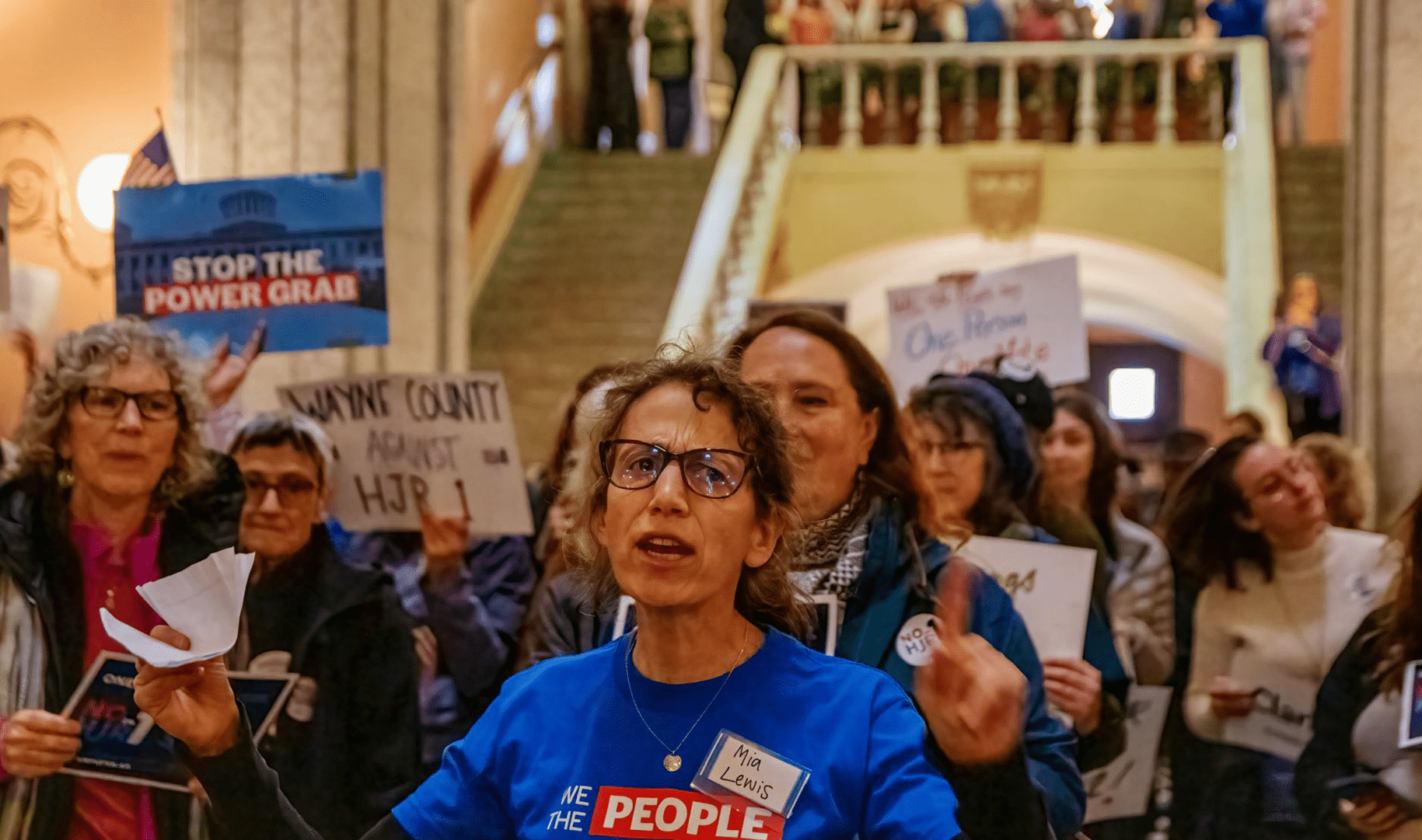

When a coalition of voting rights activists in Ohio set out last December to introduce a new ballot initiative to expand voting access, they hardly anticipated that the thing to stop them would be a matter of word choice.

But that’s what Ohio Attorney General Dave Yost took issue with when he reviewed the proposal’s summary language and title, then called “Secure and Fair Elections.” Among other issues, Yost said the title “does not fairly or truthfully summarize or describe the actual content of the proposed amendment.”

So the group tried again, this time naming their measure “The Ohio Voters Bill of Rights.” Again, Yost rejected them, for the same issue, with the same explanation. After that, activists sued to try and certify their proposal—the first step on the long road toward putting the measure in front of voters on the ballot.

“AG Yost doesn’t have the authority to comment on our proposed title, let alone the authority to reject our petition altogether based on the title alone,” the group said in a statement announcing their plans to mount a legal challenge. “The latest rejection of our proposed ballot summary from AG Yost’s office is nothing but a shameful abuse of power to stymie the right of Ohio citizens to propose amendments to the Ohio Constitution.”

These Ohio advocates aren’t alone in their struggle to actually use the levers of direct democracy. Already in 2024, several citizen-led attempts to put issues directly to voters are hitting bureaucratic roadblocks early on in the process at the hands of state officials.

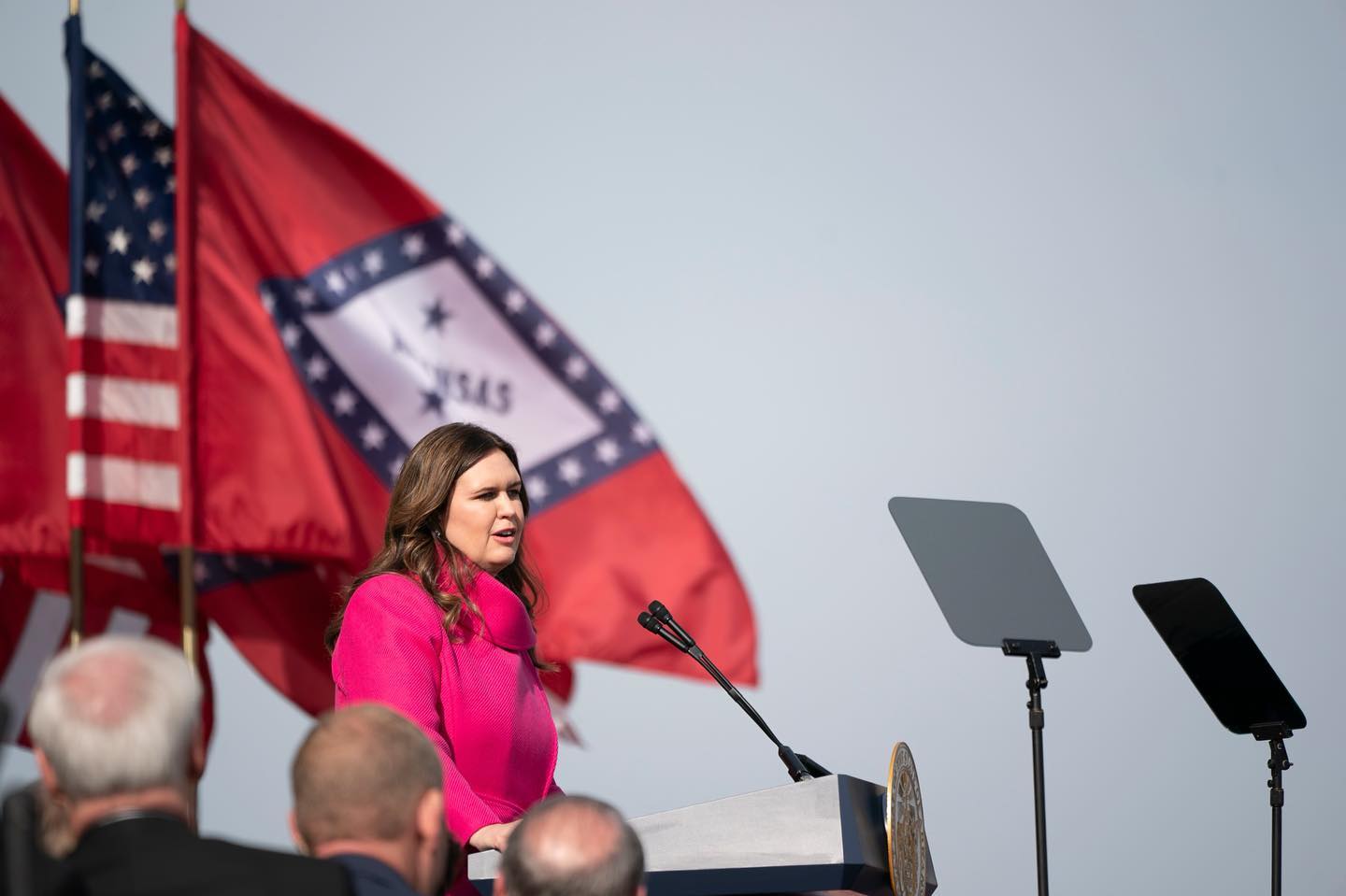

Arkansas organizers have been stonewalled by their attorney general, who has rejected language for ballot proposals to expand medical marijuana and increase government transparency. In Nebraska, a lawmaker behind a law sending more public money to private schools has leaned on the secretary of state to block a ballot referendum attempting to repeal it.

Abortion rights measures have been under particular scrutiny. Missourians attempting to enshrine abortion rights in the state constitution were delayed from gathering signatures for months as state officials fought over the specifics of the ballot measure. Advocates in Montana are still fighting to get their proposal for abortion rights approved for signature gathering after the state’s attorney general rejected it in January. Meanwhile, observers across the South are waiting with bated breath for the Florida Supreme Court to decide the fate of a proposed abortion rights initiative, which could decide whether abortion remains legally available in the region; Florida Attorney General Ashley Moody asked the court to block the proposal, saying that the language is too confusing for voters to understand.

Ostensibly, these proposals are being rejected over technicalities; a problem with a ballot title, or unclear language in the proposal. But in practice, advocates argue, the state officials reviewing these proposals are blurring the lines between procedural and political. They claim these officials are overstepping the bounds of their discretion to reject ballot initiatives based on their opposition to the underlying issue and not the quality of the petition.

“We have never seen the Ohio AG try to broaden their authority to allow them to determine whether a title is permissible,” explained Emma Olson Sharkey, an attorney specializing in ballot initiatives at Elias Law Group, one of the firms leading the suit against Yost, the Ohio attorney general. “This is clearly, from my perspective, an overreach of authority, and we are seeing similar efforts with conservative officials across the country.”

National observers say this is an escalation of an ongoing effort by leaders of mostly conservative state governments to thwart direct democracy. Bureaucratic backlash to citizen-led ballot initiatives has become a pattern in some red states. Arkansas’ Republican-run legislature last year pushed through new rules raising the signature-gathering requirements, just a few years after voters rejected those same changes. Last August, Ohio voters similarly rejected a proposal put forth by state Republicans to increase the threshold needed for measures to pass.

“It’s all part of this larger puzzle of who gets a say and who gets to participate in our democracy, and where things are popular among constituents but that does not align with whoever is in political power in that state,” said Chris Melody Fields Figueredo, executive director of the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, which tracks ballot measures around the country.

A rejection from a state official doesn’t necessarily spell certain death for a citizen-led initiative, because organizers typically have opportunities to correct problems and resubmit. But advocates for direct democracy say the long delays caused by fighting with an attorney general over the language of a ballot proposal wastes legal resources and precious time needed to collect signatures and connect with voters. In this way, even if state officials can’t kill proposals outright, then perhaps by a thousand cuts.

In the just over half of states that allow for citizen-led ballot initiatives or referendums, each one has different rules governing the process. In Michigan, a proposal is submitted to the secretary of state before signature gathering, and language is reviewed by the state Board of Canvassers. Illinois has next to no pre-approval process at all for a petition to make it onto the ballot. In Florida, by contrast, ballot title and summary language must be approved by the secretary of state, the attorney general and the state supreme court.

In evaluating these petitions for inclusion on the ballot, these state officials are typically empowered to conduct a review of the petition’s formatting, language, and adherence to state and federal laws. This may mean an attorney general or lieutenant governor making sure that a petition only applies to one subject, or that the language of a summary is easy to understand. These officials don’t have the authority to review the underlying issue a petition is about. And yet, in recent years, some of them seem to be pushing the boundaries of their clerical duties.

“It really should be more mechanical power to certify this and neutrally evaluate it,” explained Quinn Yeargain, a professor of state constitutional law at Widener University and frequent Bolts contributor. “They’re putting a thumb on the scale and pushing, I think, to expand the understanding of their power.”

David Couch, an Arkansas attorney who has spearheaded various ballot proposals for years, claims the state’s attorney tried to undercut organizers’ attempts to increase government transparency by repeatedly rejecting their proposed language for ballot measures. Couch worked with a coalition called Arkansas Citizens for Transparency last year to introduce a pair of initiatives aimed at amending the state constitution and creating a new state law to guarantee the right to access public information. The ballot initiatives were first submitted to Republican Attorney General Tim Griffin in November of last year, but he rejected one of them, on the grounds that the popular name and ballot title, “The Arkansas Government Transparency Amendment,” was not sufficiently specific.

The group resubmitted the amendment in December, offering four different options for ballot titles and other changes to the text, but the proposal was again rejected. They made a third submission in January, but before Griffin could issue a decision, Couch sued the attorney general in state court over the previous rejections.

“In my opinion, he was using his statutory authority, which is very limited, to make us rewrite the amendment and rewrite the act to weaken it, and to make it be more what he would like it to be rather than what we the people would want it to be,” Couch told Bolts.

Griffin has maintained that his rejections remained within his authority, and stated in his first opinion from December that his “decision to certify or reject a popular name and ballot title is unrelated to my view of the proposed measure’s merits.” Even so, later on in the opinion, Griffin wrote that he took issue with the word “transparency” in the ballot title, saying it had “partisan coloring” and “seems more designed to persuade than inform.”

Griffin eventually accepted both proposals, though not before one more rejection, and Couch dropped the lawsuit—not because he had a change of heart, he says, but because the coalition had already lost too much signature-gathering time. Organizers now have until July 5 to gather 90,000 signatures from voters in at least 15 counties to get the issue on the November ballot. (That threshold would be even higher under the bill Arkansas passed last year, but it’s currently held up by a different lawsuit heading toward the high court.)

“They use it to run the clock up. You lose a month every time you have to change something,” Couch said. “What he did was just wrong. It’s unconstitutional.”

In Missouri, abortion rights organizers have engaged in a nearly year-long battle with the state over a proposal to enshrine abortion rights in the state constitution and override the state’s near-total abortion ban.

After the group, Missourians for Constitutional Freedom, submitted 11 different options for an amendment proposal back in March, there was a protracted legal fight with Attorney General Andrew Bailey, a Republican. Bailey tried to force a fiscal impact statement onto the measure claiming it would cost taxpayers billions of dollars (the state auditor, who is tasked with such assessments, had initially determined the state would see “no costs or savings”).

Once the state supreme court rejected the attorney general’s attempts to inflate the cost of the amendment, the proposal moved on to Republican Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft, who was tasked with writing 100-word summaries of each option submitted. Organizers accused him of using misleading and partisan language to describe six of the proposals, and the courts ultimately agreed with them after they sued; in an Oct. 31 ruling, a state appeals court said that Ashcroft’s ballot summaries were “replete with politically partisan language,” and ordered him to use the more neutral summaries written by a lower court. Ashcroft tried to appeal the decision to the state supreme court, but they refused to take up the case.

By the time the dust settled from all this legal back and forth and Missourians for Constitutional Freedom embarked on their formal signature-gathering campaign, it was already January, eleven months since they first submitted their proposal. They now have until May 5 to gather more than 170,000 signatures to get it on the November ballot. One observer with experience running petition campaigns described the experience to The Missouri Independent as “going downhill at a very fast rate of speed.”

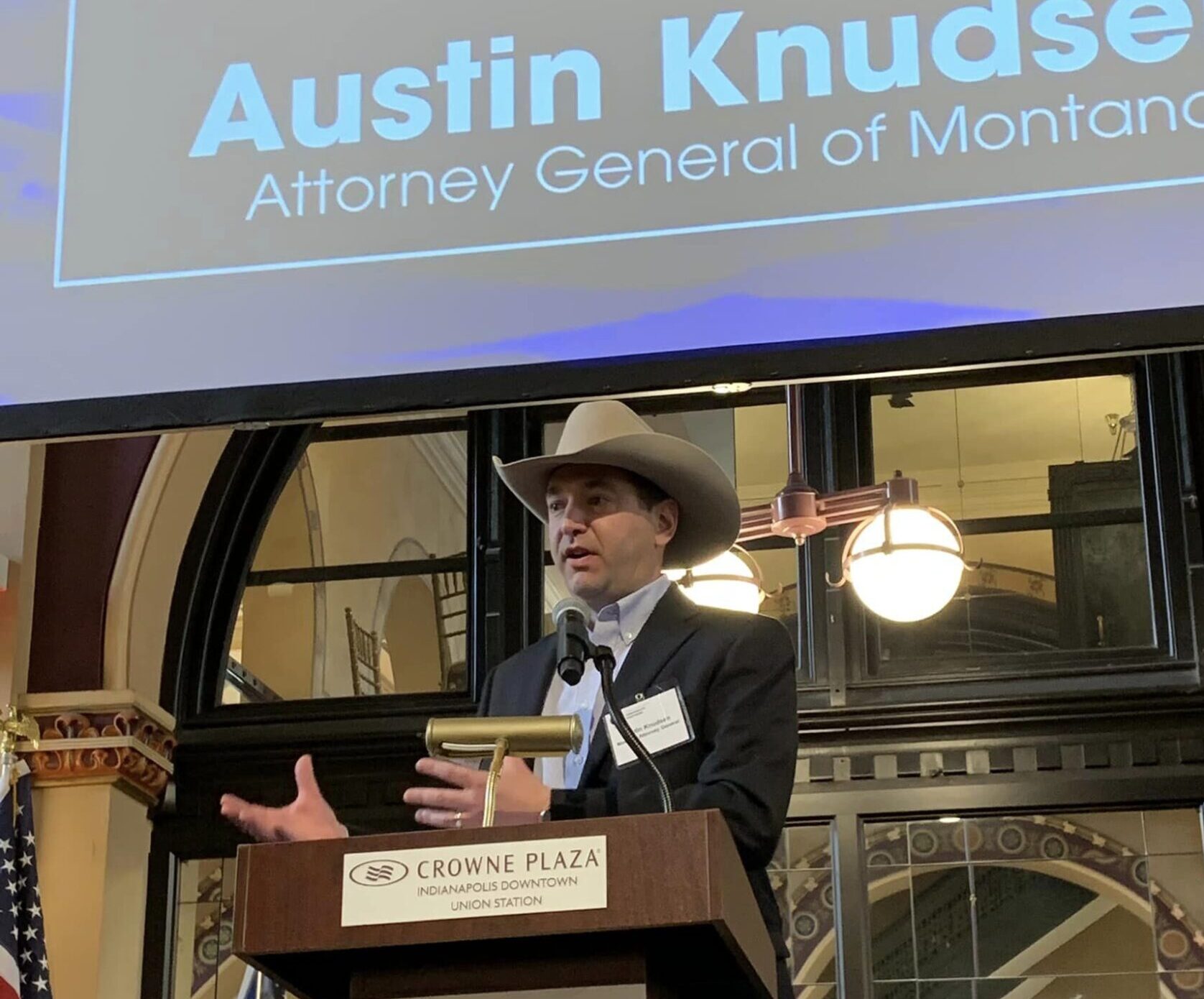

In Montana, a group backing a similar abortion rights measure, Montanans Securing Reproductive Rights, is still stuck in limbo. After state Attorney General Austin Knudsen, a Republican, rejected their measure for not adhering to the single-issue rule, the group quickly petitioned the Montana Supreme Court to overturn the decision, claiming that Knusden overstepped his bounds. They have some precedent on their side—the supreme court in November reversed a similar decision from the attorney general, after he invalidated a ballot measure to reform election rules to create a top-four primary.

“We were prepared for the fact that it was likely [Knudsen] would try to block the ballot measure and try and take up more time,” said Martha Fuller, president of Planned Parenthood Advocates of Montana, one of the groups in/leading the coalition. But Fuller says they’re not letting this delay kill their organizing momentum.

“I feel really confident in our ability to gather the number of signatures even on a tighter time frame than we are now,” she said. “Every day we’re hearing from folks who are ready to go; we’re already feeling a sense of momentum building around this measure.”

As organizers fight to get their initiatives on the ballot, they also face broader conflicts around citizen-led ballot measures. Lawmakers around the country have continued to tinker with rules governing nearly every step of ballot initiative processes. While voters in Ohio and Arkansas have rejected state attempts to move the goalposts for ballot initiatives, in others states officials have forced those changes; an analysis by Ballotpedia of legislative changes made to the initiative and referendum process between 2018 and 2023 found that roughly 20 percent of all the legislation passed made the processes more difficult.

And the changes keep coming: Just last week, Republicans in the Missouri legislature advanced two different bills that would make it harder for initiatives to pass. One passed by the Senate would require that a proposal receive majority support in five of the state’s eight congressional districts to pass, in addition to a simple majority of voters statewide. The other, which just passed in the House, would add stricter requirements for the signature gathering process.

“There’s a constant pushback from conservatives to try to stop these measures in their tracks,” said Olson Sharkey from Elias Law Group. “Because they know, especially with reproductive rights, if these measures get on the ballot, they’re going to win”

Olson Sharkey sees these tactics coming out of conservatives’ playbook, but conservatives aren’t the only ones deploying them. As Bolts has reported, the Democratic city government of Atlanta changed the rules for popular initiatives in an effort to block a proposed referendum against the ‘Cop City’ police training center; the city council earlier this month went as far as to approve the controversial practice of signature matching to disqualify some people who signed the petition.

For Fields Figueredo, who tracks ballot initiatives across the country, no matter who’s responsible, chipping away at ballot initiatives betrays a disregard for the fundamental principles of democracy.

“It’s ultimately about minority rule,” she said. “We could elect people in a democratic process, and also they are not actually listening to the will of the people.”

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.