‘We Have a Right to Put It on the Ballot’: How Organizers Are Defending Direct Democracy

Bolts invited three organizers in Arkansas, Idaho, and Ohio for a roundtable to discuss the attacks on ballot initiatives they are each fighting in their states, and lessons they’ve learned.

Daniel Nichanian | August 16, 2023

The resounding defeat of Ohio’s Issue 1, a constitutional amendment that would have undercut direct democracy in the state, received wall-to-wall coverage last week because it salvaged the prospect that Ohioans may adopt a ballot measure protecting abortion rights in November.

Abortion advocates rejoiced, but for some organizers watching around the country, the result was especially exhilarating because it spoke to the fight they’re going through in their own backyards to defend direct democracy.

South Dakotans last year defeated an amendment similar to Ohio’s, which came on the heels of initiatives to increase the minimum wage and legalize cannabis and would have kneecapped a measure to expand Medicaid. In Arkansas, the GOP repeatedly asked voters to limit the initiative process but lost repeatedly at the polls; this year, they adopted new restrictions anyway. Idaho organizers in 2018 expanded Medicaid through a ballot measure, and the GOP keeps trying to make initiatives harder ever since.

Anti-initiative proposals just keep popping up in many other places, including Arizona, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Utah. And they reemerge even after they’re defeated, forcing proponents of direct democracy to dedicate capacity and resources to protecting the rules of engagement—and to constantly look over their shoulder.

Bolts this week gathered three organizers who have fought this dynamic in each of three states that are undergoing this dynamic: Ohio, Arkansas, and Idaho. Their meeting sparked a wide-ranging conversation about their shared frustrations and strategies.

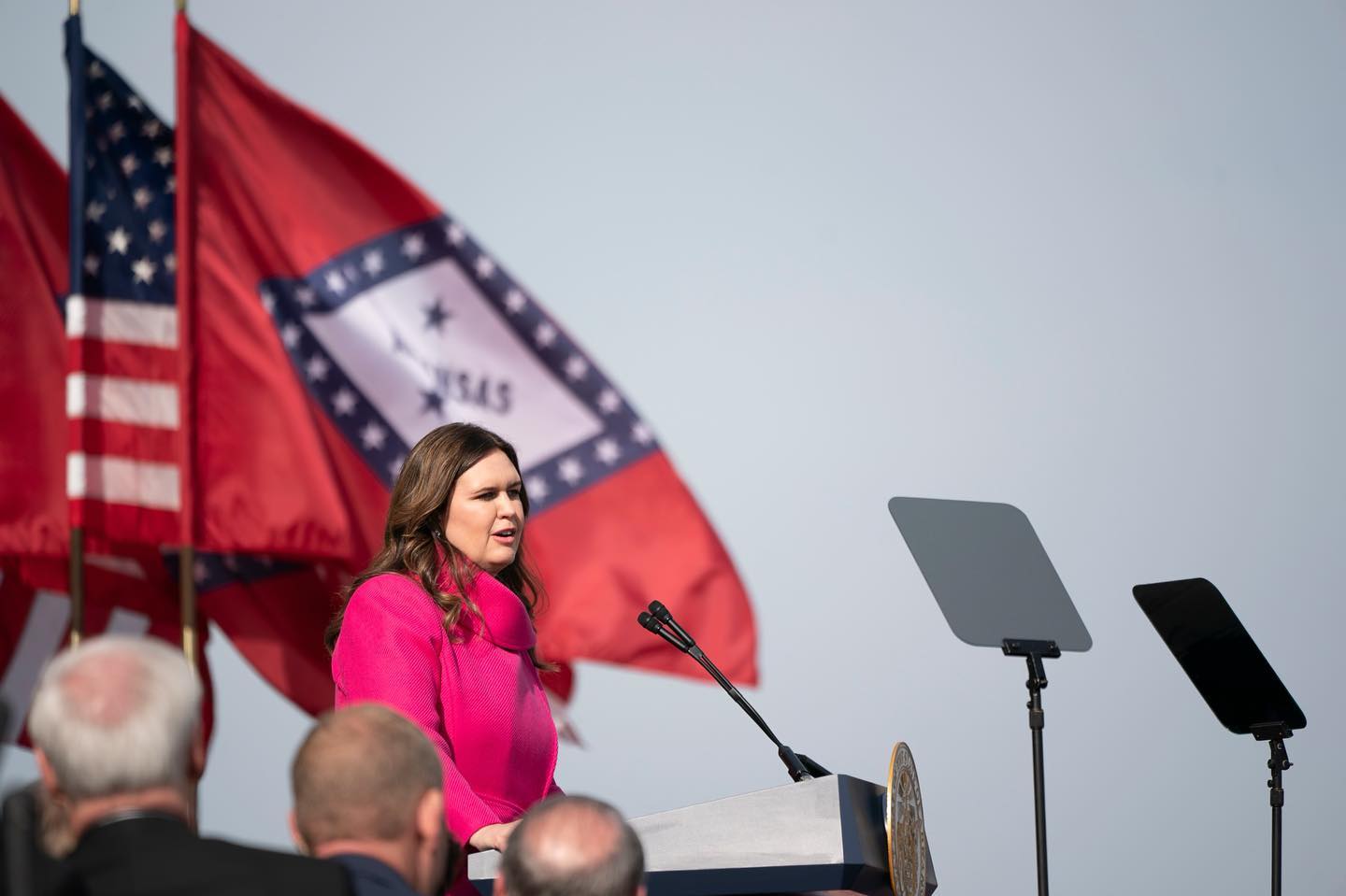

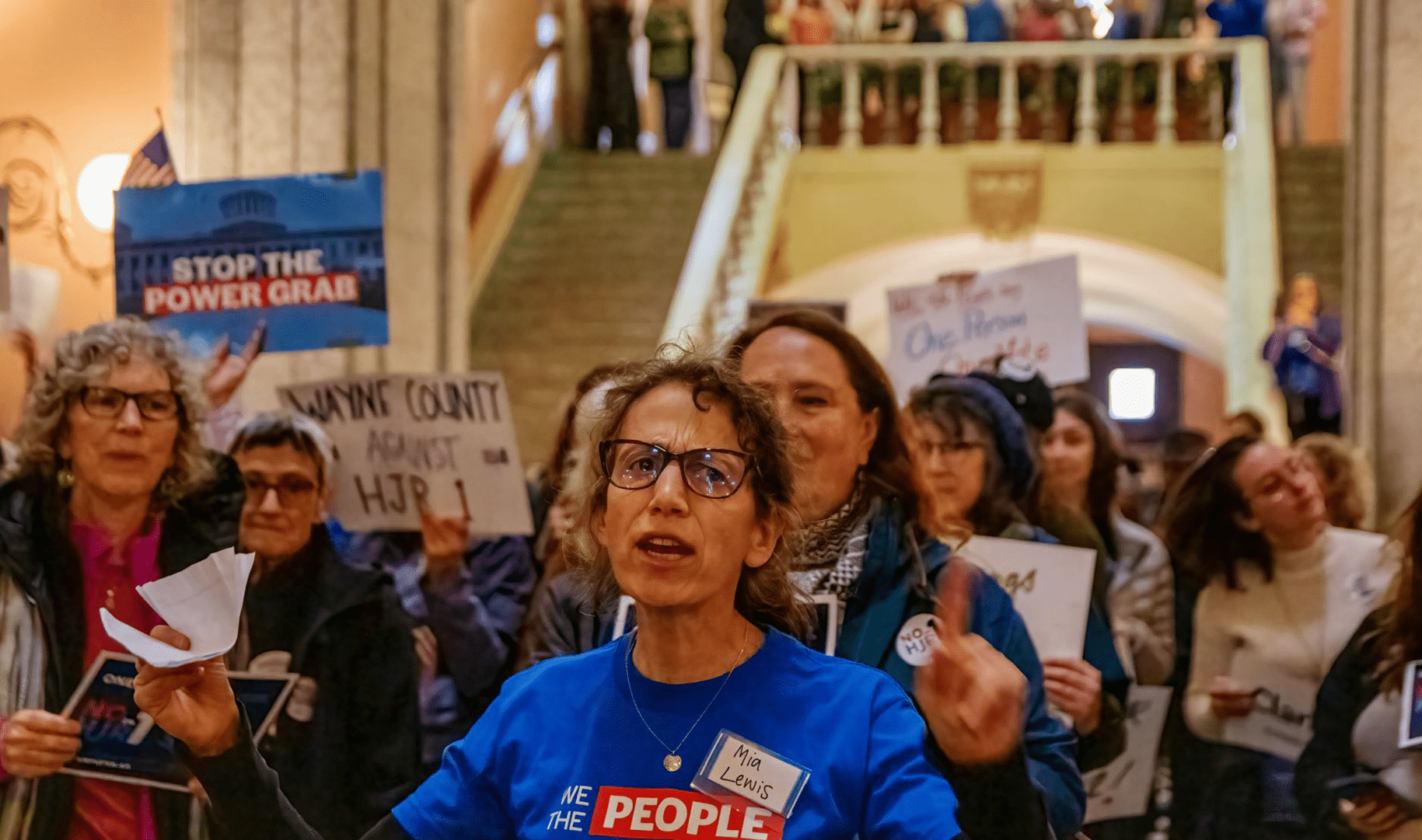

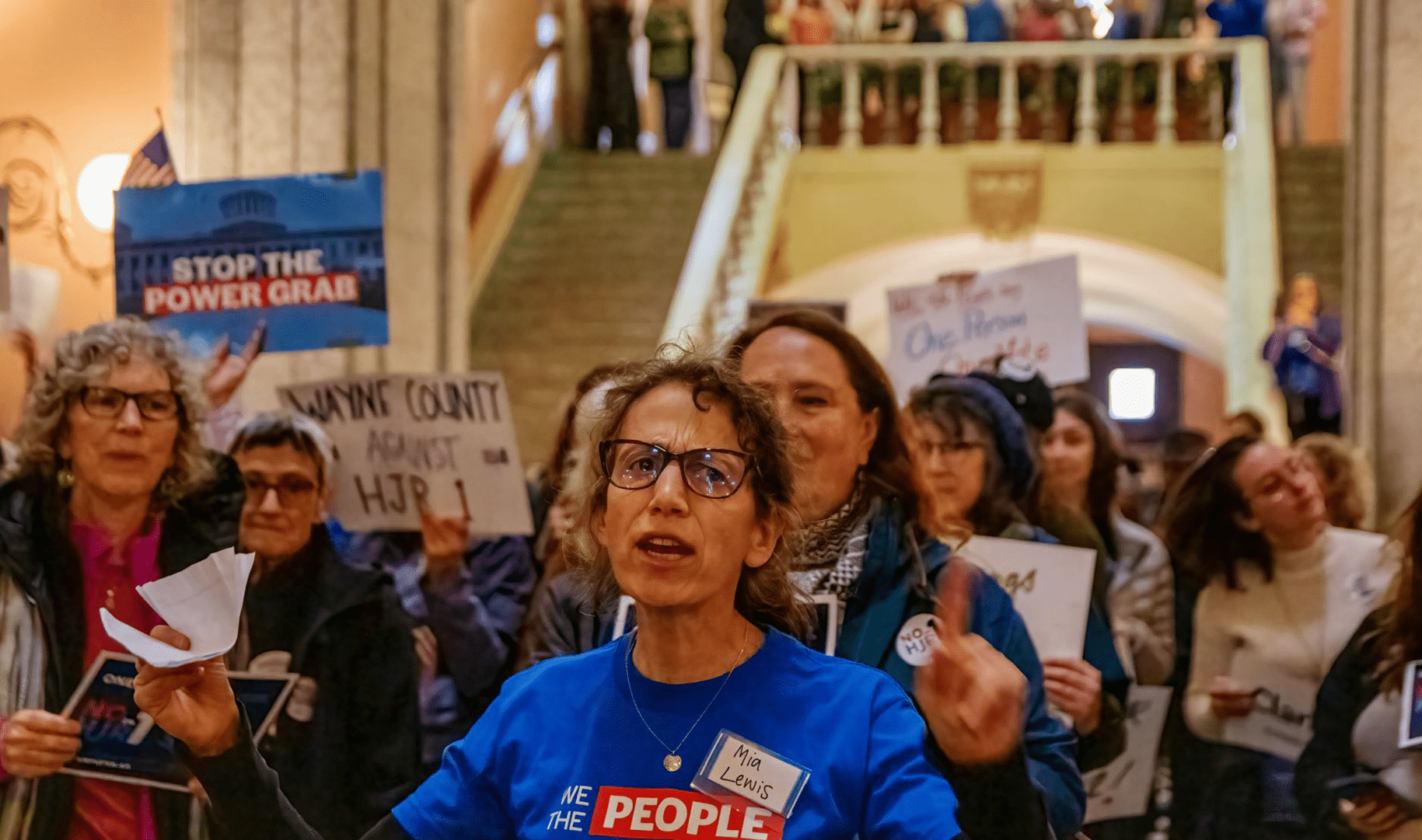

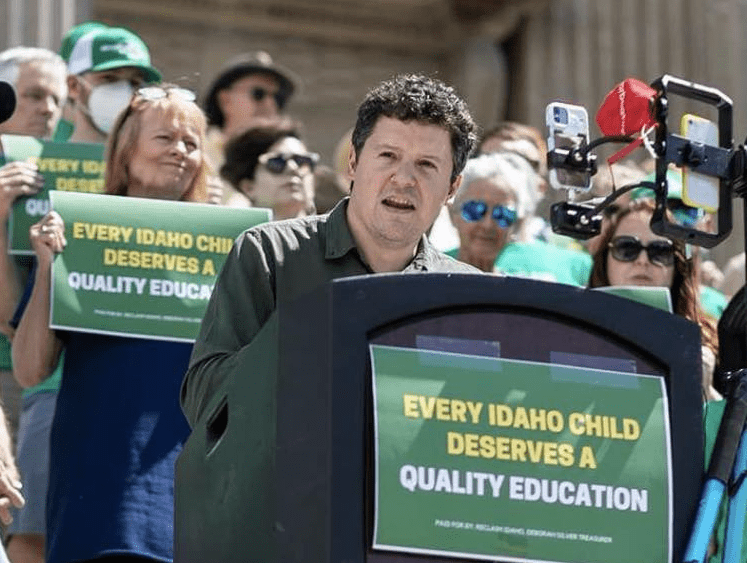

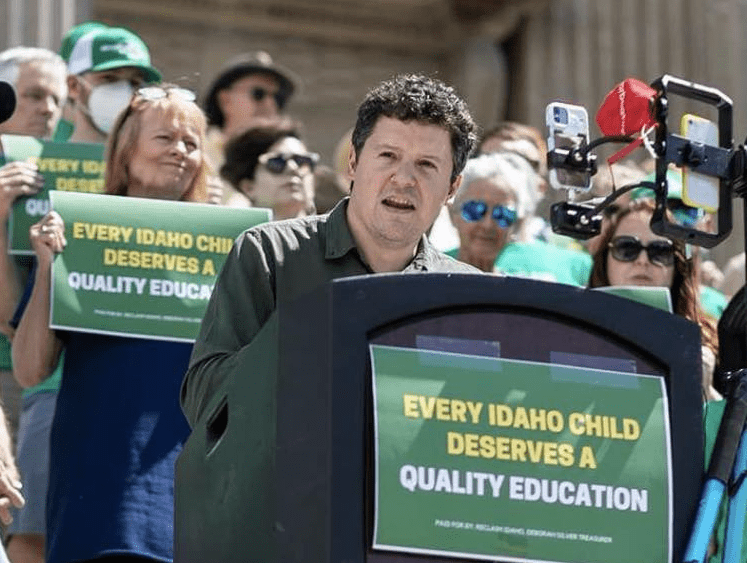

Mia Lewis, associate director of Common Cause Ohio, was active in the campaign to defeat Issue 1 this summer. Kwami Abdul-Bey, elections coordinator at the Arkansas Public Policy Panel, helped form a coalition to defeat a similar measure in Arkansas last year. As the co-founder of Reclaim Idaho, Luke Mayville launched the initiative to expand Medicaid in 2018 and he has since organized to defend the initiative process in Idaho.

In a conversation that took place days after Ohio’s election, they took stock of the fights they are embroiled in together and discussed what explains their convergence. “Oligarchic agendas,” Mayville said, “have everything to gain from shutting down the initiative process.” They’ve each worked separately to protect initiatives in their states, but the attacks they faced and the lessons they learned are similar, and they shared organizing and messaging tips with one another.

“This is a great group to be talking to,” Lewis said. “Because they’re not doing this in one state, they do these things repeatedly in different states, so why shouldn’t we strategize?”

What attacks on direct democracy have you each fought in your own states?

Luke Mayville (Idaho): We came on the scene in 2018 with a ballot initiative to expand Medicaid that was successful. The legislature reacted by attacking the initiative process. The big showdown came in 2021, when they passed a very restrictive law that would have made it impossible to get future initiatives on the ballot. We sued and got a unanimous decision by the state supreme court striking down that anti-initiative law: They declared for the first time that the initiative process is a fundamental right, and that sent a really strong signal from the court to the legislature. But they came back again this year: They took the rules that had been struck down and tried to put it into the constitution. We put together a bipartisan coalition in the House and blocked the amendment. But we anticipate that they will try again in the next session.

Kwami Abdul-Bey (Arkansas): Ours was because in 2016 and 2018, we were successful in increasing the minimum wage and passing medical marijuana. The response to us doing that was, ‘we’re going to fuck you guys by not allowing you to do this again.’ It happened twice: In 2020 and again in 2022, they tried to increase the percentage [for future initiatives to pass] from a simple majority to 60 percent. They were defeated in both years. This year, they just said, ‘OK, since we can’t get this in the Constitution, we’ll just write a law.’ They wrote a law increasing geographic requirements [for signatures], and that’s currently in front of our supreme court. Your supreme court win in Idaho would be very instructive, Luke, and I’d love to read what it has said.

Mia Lewis (Ohio): In Ohio, Issue 1 was a response to the fact that reproductive rights was going to be put on the ballot this November, so they wanted to make sure that the pass rate was higher. At first they said it’s not about abortion rights, but the important people that were pushing this would admit, in semi-private situations, that it’s 100 percent about abortion. And they’ve already said that they’re going to come back and try again, so we’re expecting that.

All of you have described these anti-initiative reforms as direct responses to groups like yours working on specific initiatives. What would you say is fueling that reaction?

Lewis: A lot of the attacks on direct democracy are linked to the abortion issue, and if it’s not an abortion issue, it’s something else where they don’t like an answer that the people gave. If they don’t get the answer that they want at the polls, or if they’re afraid of the answer that they might get at the polls, well, ‘we’ll change the rules and we’ll make it harder for people to be able to express themselves.’

Our society is filled with these billionaires who want to be able to buy whatever they want, and corporate interests are not satisfied with just letting democracy take its course and listening to the people. Direct democracy is the thorn in the side of these billionaires and corporate special interests, and they don’t want to be thwarted.

Mayville: It really is in the last 10 to 15 years that there’s been a wave of organizers in states realizing that the initiative process can be a powerful way to address social and economic injustices, and picking up that tool and running with it, in many cases overcoming huge odds to get these things on the ballot. If you’re a special interest group that’s mastered the craft of lobbying legislatures, the initiative power is a very scary thing. It’s harder to control the decisions of the general public than of 100 legislators in the state capitol.

Some agendas only really have people power on their side, others have people power and quite a lot of money. But then there are a whole lot of agendas that only have the money, and they’re deeply unpopular: I would call them oligarchic agendas. And those agendas have everything to gain from shutting down the initiative process. The payday loan industry, for example, has been fiercely opposed to initiatives. There was an anti-initiative law proposed in 2019 [in Idaho], and we learned from an investigative article that the legislator who sponsored it had consulted with a payday loan industry lobbyist, and was exposed in the middle of the fight for it.

The battles you described in each of your states are very similar to one another. Would you characterize the current situation as a national attack on direct democracy, or would that be simplifying differences between state contexts?

Mayville: It certainly appears that there is a nationally coordinated attack on the initiative process; my understanding is that dismantling the initiative has been a major objective of organizations like the American Legislative Exchange Council and various corporate special interests across the country. The main agenda is to undercut any exercise of collective power to address social injustice, economic injustices.

Abdul-Bey: Luke mentioned ALEC, and when you look at a bill that lands on a committee here in Arkansas, that has the same language that it has in Ohio and Idaho, we know that there’s something going on that’s producing all of this legislation.

What we are guilty of, is we’re guilty of not really being prepared for this onslaught, and so we’re trying to catch up. In Arkansas, we work with a national organization called BISC, the Ballot Initiative Strategy Center, and BISC has trained me as a ballot measure leader and also helped us put together messaging and create a statewide coalition, both on the left and the right, where we’re able to agree that this fundamental right of direct democracy. When you called me, Daniel, I was actually at a BISC training in St. Louis, where there were about 16-17 states represented, and we were comparing notes and trading techniques.

In fighting these anti-initiative proposals, what messaging and argument have you felt are especially successful?

Abdul-Bey: Here in Arkansas, the state motto is, “the people rule.” So we used that state model as our foundation. We just go out and remind them that our state motto is the people rule. How can the people rule if we are not allowed to put forth constitutional amendments, legislative measures, and veto referendums?

In addition, our constitution states that the power of the state rests in the people, and that the people loan their power to the legislature, the governor and the judiciary, so we’re able to use that in our messaging to basically have a civics lesson for our citizens. You can’t go out and just change the rules so that you can win; when you change the rules in your favor, you’re cheating.

Lewis: I want to say straight up that we designed a flier that we distributed, over 250,000 of them, all across the state, and I based that 100 percent on messaging from Arkansas: The messaging that, ‘corrupt politicians and special interests are trying to trick voters into giving up their power, giving away their rights,’ that was from Arkansas. So I’d like to thank you.

I really feel like that encapsulated the issue: They’re trying to trick you into giving up your power. And I would say, I don’t want to wake up on Wednesday with fewer rights than I had on Tuesday. They have enough power, we need our own power. This messaging about freedom and rights is very cross partisan. On the one side we have the people and on the other we have the corrupt politicians and special interests who are bankrolling them.

Mayville: I love that you’re trading these messages about how they’re trying to take the power of citizens away. We found that to be such a powerful thing. When legislators were trying to convince one another, you would hear them making arguments against democracy—the John Birch argument that ‘we’re not a democracy, we’re a republic.’ The minute they start having to appeal to ordinary voters, they drop that argument and have to divert attention. Because if it’s a debate about whether ordinary people should have a lot of political power, it’s an 80/20 issue.

In addition, when you’re waging these battles, it’s incredibly powerful to draw on the traditions of your own state. We found that there’s this very strong appeal we can make to the constitutional heritage of Idaho, the fact that we have had these constitutional rights for over 100 years.

Ohio’s Issue 1 only addressed the rules of direct democracy, but it also became a proxy battle over abortion rights. Is it helpful in defending direct democracy when the debate focuses on the underlying substantive issues, or does it complicate things?

Lewis: That’s a complicated question. The official ‘vote no’ campaign didn’t want to be too tightly associated with reproductive rights because they correctly saw that it was about many other things. But the ‘vote yes’ campaign tried to tie it to abortion. And on the ground with the volunteers [for the ‘vote no’ campaign] who were out there spreading the word, damn straight they cared about abortion. Damn straight, they wanted to protect their rights and not have them taken away. So yeah, that was an issue for individuals on the ground who care about this.

Mayville: It’s important to think carefully about exactly what message is going to resonate, and that again echoes back to the corrupt politicians and special interests trying to take away your power. That’s the ten words that you repeat a million times.

Take the issue we’re most known for, Medicaid expansion, and take the issue of initiative rights: As soon as we went out and started talking with ordinary people, we immediately found that initiative rights had broader appeal. And that’s saying a lot because Medicaid expansion got 61 percent of the vote [in 2018]. People would come up to us and say, ‘I don’t necessarily agree with that initiative you all did, but you had a right to put that on the ballot.’ Similarly, it’s a very common occurrence when you’re getting signatures that people say, ‘I’m not sure I agree with you, but I want this to be on the ballot so that voters can have a chance,’ and they’ll sign it.

Abdul-Bey: We train our canvassers who collect signatures—and Luke spoke to this—to tell people that you’re not signing this to determine your agreement. You’re signing to determine that we have a right to put it on the ballot, that you support the concept of direct democracy.

Also, we’ve been very successful in reminding the people of Arkansas that we would still be at $7/hour minimum wage if it were not for our successfully getting the minimum wage on the ballot. Working-poor Arkansans know the benefits because they have lived with the benefits, and we remind them, ‘Hey, you are paid this much an hour because of this type of work.’

You’ve all described the relentlessness of this fight, and I can imagine the toll that takes on you and your organizations. So where does that leave you today—more optimistic or nervous?

Lewis: We’re feeling good! We’re pumped because we feel like we won to keep our right to direct democracy, and dammit we’re going to use it. I think the fact that reproductive rights are on the ballot in November helps people feel mobilized: whether or not that’s an issue you support, just the fact that people get a chance to vote. Recreational marijuana is also going to be on the ballot, and then redistricting is right around the corner. We know they’re already plotting something, of course we do, but we’re trying to feel optimistic right now about it for sure.

Mayville: It can be very exhausting. We were in the middle of a debate on school vouchers, and in the middle of that there’s this constitutional amendment fight over the initiative process. We’d already fought twice on that issue, we thought we had put it to rest with a unanimous supreme court ruling. However, the way we’ve decided to think about it, which I do think is the right way for organizers in states to take on this challenge, is to see it as an organizing opportunity: For all of the exhaustion, this is an issue that has much broader support than most of the other issues that we’re organizing around, so it’s really this extraordinary opportunity to use the issue of initiative rights as a bridge to connect people and start a conversation.

Abdul-Bey: One thing we do in Arkansas is we not only use it to organize but also to strategize for the future. A ballot measure that we’re in the process of authoring is to enshrine those initiative rights within the constitution, using what we’ve learned over the last seven years to plug all of the holes that they have tried to run 18-wheelers through.

And we’re reaching out to the Lukes and the Mias of the world, and working with BISC, to make sure that we are all unified, working together and using that collective energy to maintain this battle. It is tiring, but at the same time, it’s rejuvenating. And when we heard of Mia’s win, we celebrated and partied because we know that what happened in Ohio is an example of us turning the tide around.

The roundtable has been edited for length and clarity.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.