The California Ballot Measure That Could End Forced Prison Labor

Prop 6 would amend the state constitution to ban “involuntary servitude” and prohibit state prisons from punishing incarcerated people for refusing a work assignment.

| September 26, 2024

The last job that Jared Villery had before his 21-year prison sentence ended was working “quick chill” in the main kitchen at Valley State Prison in California, where he would help flash freeze meals to be dispersed for the entire population. The job required Villery to lift trays that he said could weigh up to 60 pounds. But Villery had cartilage damage to his right knee, for which he had metal plates, and he also had pins in his ankle. He said it hurt to do any heavy lifting.

On several occasions, Villery told officers about his knee and that he could be injured on the job. He asked them to put him in a different position, but they refused and threatened to give him a write up if he didn’t work, which would have impacted his impending parole board hearing. Villery was worried that speaking up might cost him his release date. He had no choice but to work the job.

“I couldn’t refuse or else I’m guaranteed denial of parole, you know, I’m not going to go home,” Villery said. “So I worked, and I kept doing the job.”

Just as he’d warned, Villery’s knee buckled one day when he was lifting a tray out of the freezer, which caused him to fall and hit his head. He had to walk with a cane for two years after that.

“All of it could have been avoided if I had any say whatsoever in how job assignments are made,” Villery said. “But they don’t care. All that mattered was filling the positions.”

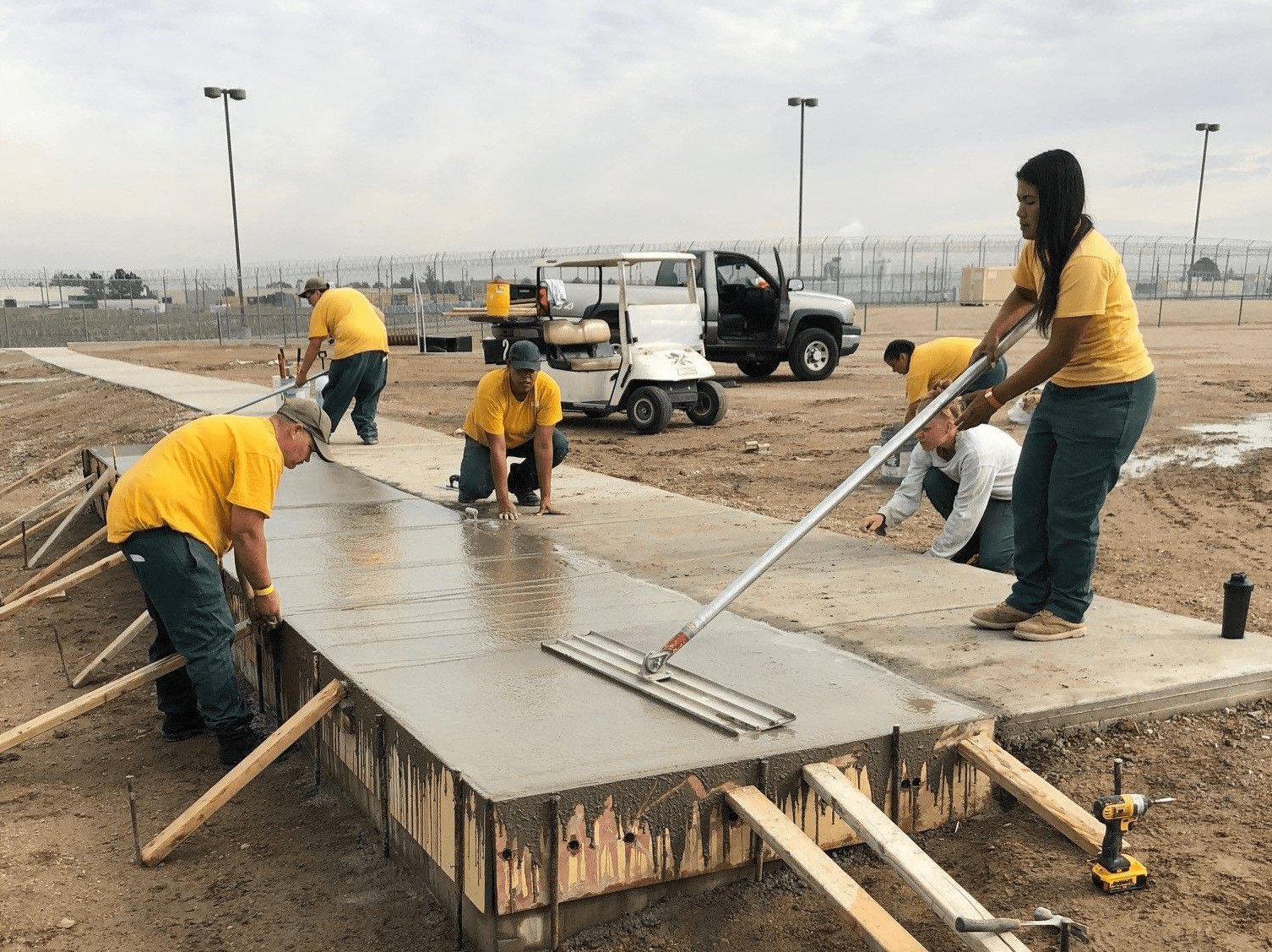

Like Villery, many people incarcerated in California don’t have a say in the job they work, and can be met with retaliation if they refuse. They can be forced into prison labor because the state never fully abolished slavery.

California’s state constitution contains the same loophole that’s in the 13th Amendment to the federal constitution, which formally abolished chattel slavery but allowed it to continue as punishment for crime. This allows prisons to force incarcerated people to work jobs they have little to no say in for as little as pennies an hour. Even if someone wants to attend rehabilitative programs or college classes to prepare them for reentry, they can be forced to miss out on those opportunities to work jobs like yard crew, kitchen staff or janitor, which advocates say is counterproductive to the supposed goals of rehabilitation.

In November, Californians will vote on whether to end forced labor in the state’s prisons and jails. Proposition 6, which will appear on the statewide ballot, would amend the state’s constitution to ban involuntary servitude behind bars and prohibit punishment for refusing work assignments.

If passed, the amendment would make California the latest state to close the prison-labor loophole by adding anti-slavery language to state constitutions. In 2022, voters passed anti-slavery amendments in Alabama, Oregon, Tennessee and Vermont.

Nevada is the only other state this year to be voting on a similar measure. California and Nevada are currently among 16 states that haven’t closed the loophole.

In California, a coalition of advocates, many of whom are formerly incarcerated, have pushed for years to amend the state constitution. They say banning involuntary servitude will give more agency and dignity to people in prison.

“Forced labor does no good for anyone,” Villery said. “If you are stealing someone’s decency, the innate human dignity that they have by telling them ‘We’re going to force you to do whatever we want’, I don’t see how anybody can ever truly rehabilitate in that situation.”

J Vasquez never minded his work as a porter in a California prison—the job got him out of his cell. But as he started turning his life around, he wanted to seek out programming to focus on healing and accountability. Vasquez had heard about a victim impact class that he wanted to attend, which would help him learn more about the harm he caused. He wasn’t allowed, though, because it interfered with his responsibilities of sweeping and mopping the prison floors.

“Had I put down that broom and went to that victim impact class to take accountability, to learn about the ripple effect and victimization and to work on my own healing journey, I would have gotten a write up,” Vasquez said. “I would have been punished.”

Like Vasquez, many people in prison may be forced to miss out on healing and rehabilitative programs if they conflict with a job. Vasquez said that having people work meager prison jobs does not get to the core issue of whatever trauma or underlying problems people faced when they entered the system. Work assignments can sometimes make it impossible to attend Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, substance abuse treatment, anger management classes, trauma awareness sessions and college courses with opportunities to earn a degree, said Vasquez.

“People should not be punished for simply trying to better, heal and rehabilitate themselves,” Vasquez said. “That’s what Prop 6 would do, give incarcerated people the autonomy, the agency to choose what rehabilitative path works best for them at the moment where they’re at in their life.”

A representative for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation told Bolts that it has already made some changes since April in alignment with Governor Gavin Newsom’s “California Model”, including raising the minimum wage from eight cents an hour to $0.16 an hour, and transitioning up to 75 percent of full-time jobs to part-time.

“CDCR’s goal is for every incarcerated person to take advantage of positive programming and rehabilitative opportunities such as education, self-help, vocational and other programs,” said the spokesperson. “These career pathways are intended to ease the transition back into their communities and reduce recidivism.”

Advocates for the amendment say prison jobs don’t prepare people for reentry, and that the low pay can make it harder to reintegrate into society and be successful once released.

“We’re contracted as laborers inside the prison, and the system reaps the benefits as well because we do not have any funding that goes to our social security or retirement,” said Ivan Serrano, peer support specialist at Starting Over, an organization that offers transitional housing and reentry services to formerly incarcerated people.

When Serrano was serving a 25 year sentence at Valley State Prison in Chowchilla, his job assembling eyeglasses was considered one of the better jobs because he made 87 cents an hour.

Even though he was able to learn skills from the job, Serrano says it did little to help him find work after release from prison, which was already an uphill battle because of his felony.

He said giving incarcerated people more say over their work would help them better prepare for life outside.

“Forced labor inside doesn’t provide the options to educate yourself or anyone that is serving time in our prison system, because you do not have an option,” Serrano said. “They just tell you that this is the line of work you’re going to do, and you have to do it. You have no choice.”

Villery says his experience with his “quick chill” job wasn’t the first time he had problems with supervising officers. While working a job as a porter in 2015, he faced retaliation from officers who antagonized him for his history of filing complaints. He said that at one point, they even turned away his family after they had driven two hours to see him, using his job assignment to justify canceling the visit.

Even when Villery did get a doctor to issue a medical restriction saying he couldn’t go up stairs, he said officers would tell him to clean the top floor of the prison despite knowing about his bad knees. He says that one time when he refused to climb the stairs to the top tier, officers took away his property, restricted his access to showers and put him in solitary conditions where he was only allowed to leave his cell an hour a day up to three times a week.

“They held it over my head for months, that if I did anything they didn’t like, they would write me up in connection with that job assignment, because they were my supervisors,” Villery said.

If someone refuses to work, they can also face issues with the parole board when determining their release, Villery said. Sometimes getting a write up can result in loss of good time credits, which usually take time off a person’s sentence, making the time they stay in prison even longer.

Villery, a fellow with the Anti-Recidivism Coalition who has been active in the campaign to pass Prop 6, says he hopes it will take away some of that discretion away from correctional officers and give people inside more control over their lives.

“It’s something that’s so long overdue, having spent so long inside and seeing just the core coercive nature that officers have and the way in which job assignments are used as more punishment than like character development,” Villery said.

A large network of grassroots organizations, as well as other nonprofits across the state, have been advocating for years to stop forced prison labor, since the End Slavery in California Act was first introduced in 2020. That measure passed the state Assembly with bipartisan support but died in the Senate in 2022 after opposition from Newsom’s administration, which raised concerns about how much it might cost. Newsom’s finance department opposed the measure, warning it could cost around $1.5 million to pay people in prison a minimum wage—a policy that was nowhere in the amendment.

Activists continued to rally around the amendment and proposed it again last year, with added language allowing the state to set up volunteer work assignments for people to earn credits to take time off sentences. Lawmakers passed it this summer, putting the issue on the ballot for voters this fall.

Most of the advocates who have been pushing for the change are formerly incarcerated themselves or have loved ones in prison. Ahead of the November vote, they have been holding rallies, promoting the ballot measure on social media and educating the public about the dynamics of forced prison labor inside California prisons. Advocates say they often find that the public is not aware that a form of slavery still exists in California. A poll of likely voters conducted in September by the Public Policy Institute of California showed 50 percent opposed to the measure and 46 percent in support.

“One of the most important things that we’re fighting for is for people just to have the autonomy to be able to choose how they want to spend their time when they’re incarcerated and not be penalized when they choose not to work,” said Stephanie Jeffcoat, founder of Families Inspiring Reentry and Reunification for Everyone.

“This would mean a lot to the people inside, because they don’t have to no longer live in fear of being punished for not going to work,” she added.

Opponents of Prop 6 say that incarcerated people should be required to perform work that helps offset the costs of their incarceration. The editorial board for the San Diego Union Tribune recently urged voters to reject the amendment, arguing it could undermine victims’ rights “by allowing prisoners to refuse to make court-ordered restitution payments.”

If the amendment passes, advocates say that many incarcerated people will still seek out work to get outside of their cell. Someone might do yard crew just to spend extra time outside, or work in the kitchen to have more access to food. They say Prop 6 would just give consent to the work arrangement and give the people inside more autonomy.

Even if voters pass it, the amendment alone might not immediately end forced labor in the state’s prisons.

As Bolts reported last year, incarcerated people in Colorado, the first state to pass an anti-slavery amendment in 2018, are still punished for refusing work assignments long after the vote.

Vasquez says that advocates for Prop 6 hope that it will allow people in prison to have more say in their job decisions and rehabilitative path. He says that if the measure passes, advocates are prepared to ensure CDCR implements it.

“We want to actually change the conditions for the people on the inside to go to choose what jobs they want to work at, whether they want to work in rehabilitation or education or drug treatment instead of a job,” Vasquez said. “We want to make sure that that is going to happen in practice.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.