Forced Labor Continues in Colorado, Years After Vote to End Prison Slavery

Coloradans voted in 2018 to amend their state constitution to ban forced labor in prison. Years later, incarcerated people are still being punished for refusing work assignments.

Moe Clark | September 19, 2023

Throughout Abron Arrington’s decades-long incarceration in Colorado, he often found himself in solitary confinement—not because he was causing trouble, but simply because he refused to work. He didn’t see the point given he was paid 13 cents an hour and figured his time could be better spent learning physics.

Before Arrington was incarcerated in 1989, he was studying to get his aircraft mechanic license. But within weeks of returning home from the U.S. Air Force, at 22 years old, he was arrested and ultimately sentenced to life in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. In 2019, he received clemency from Governor Jared Polis and was released after three decades behind bars.

“I was actually 30 years a slave,” Arrington, who is Black, told a crowd of people gathered in one of Colorado’s oldest Black churches on Juneteenth, the federal holiday that commemorates the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. “So, this is deeply personal to me.”

As part of an event celebrating Juneteenth, Arrington sat on a panel to discuss prison labor, which panelists referred to as the last frontier of slavery in the United States. While the 13th Amendment of 1865 formally abolished chattel slavery, it legally remained as a punishment for crime.

Michael Gibson-Light, an assistant professor of sociology and criminology at the University of Denver and author of the book “OrangeCollar Labor: Work and Inequality in Prison,” said during the panel that “slavery was not abolished” with the ratification of the 13th Amendment, “it just changed. It evolved, it transformed.”

“Laws popped up that made it easier and easier for criminal legal institutions to continue to literally capture and extract the labor of the very same people whose labor was extracted under chattel slavery,” he added. “But now, the justifications were different. They had to do with law-breaking. They had to do with vagrancy. They had to do, eventually, with drug use.”

In 2018, after years of community organizing, Colorado sparked a national movement when voters overwhelmingly passed Amendment A, a ballot measure that deleted half a sentence from the state constitution that allowed slavery and involuntary servitude “as a punishment for crime, whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” Colorado was the first state to do so since the signing of the 13th Amendment. Since Colorado removed its language, Utah, Nebraska, Vermont, Oregon, Alabama, and Tennessee have followed suit with similar constitutional amendments. Organizers in around a dozen more states are now pushing to get similar ballot measures in front of voters during the 2024 elections.

“This is a fast-moving train,” said Kamau Allen, the lead Colorado organizer and the co-founder of the Abolish Slavery National Network.

But in some ways, Colorado’s Amendment A only abolished prison slavery on paper. That’s because the Colorado Department of Corrections (CDOC) has continued to punish those who refuse to work. Since 2018, there have been at least 727 documented instances where an incarcerated person was disciplined for failing to work, according to a 9News investigation this past summer, with punishment ranging from changes in housing to loss of privileges and delayed parole.

Now, some of the same organizers who crafted Amendment A are hoping to strengthen the state’s anti-slavery law through litigation. A lawsuit filed against Polis and his Department of Corrections in state court last year contends that compulsory labor in prison under threat of punishment and coercion violates the amendment approved in 2018. The plaintiffs, two incarcerated men who say they were punished for refusing work assignments that increased the risk to their health during the pandemic, are seeking a permanent injunction requiring Colorado prisons to “cease requiring compulsory labor” and a court order “declaring unconstitutional the statutes and regulations that mandate incarcerated people must work against their will.”

Advocates said the lawsuit—and their organizing efforts outside the court—are focused on banning forced labor, not whether incarcerated people have opportunities and incentives to work behind bars. They say they are not trying to get rid of prison work programs.

“That’s never been the intent,” said Kym Ray, a community organizer with Together Colorado who helped draft Amendment A. “People do want to work, they want the opportunity to earn money.”

“The intent is to give people the choice,” she added.

Today, incarcerated workers produce more than $2 billion each year in goods and commodities, and over $9 billion in services for the maintenance of the very prisons that confine them—all while being paid pennies an hour or nothing at all, according to research conducted by the American Civil Liberties Union and the University of Chicago Law School’s Global Human Rights Clinic. Their labor enables mass incarceration by offsetting the cost of the country’s ballooning prison system, which has grown by 500 percent over the last 50 years.

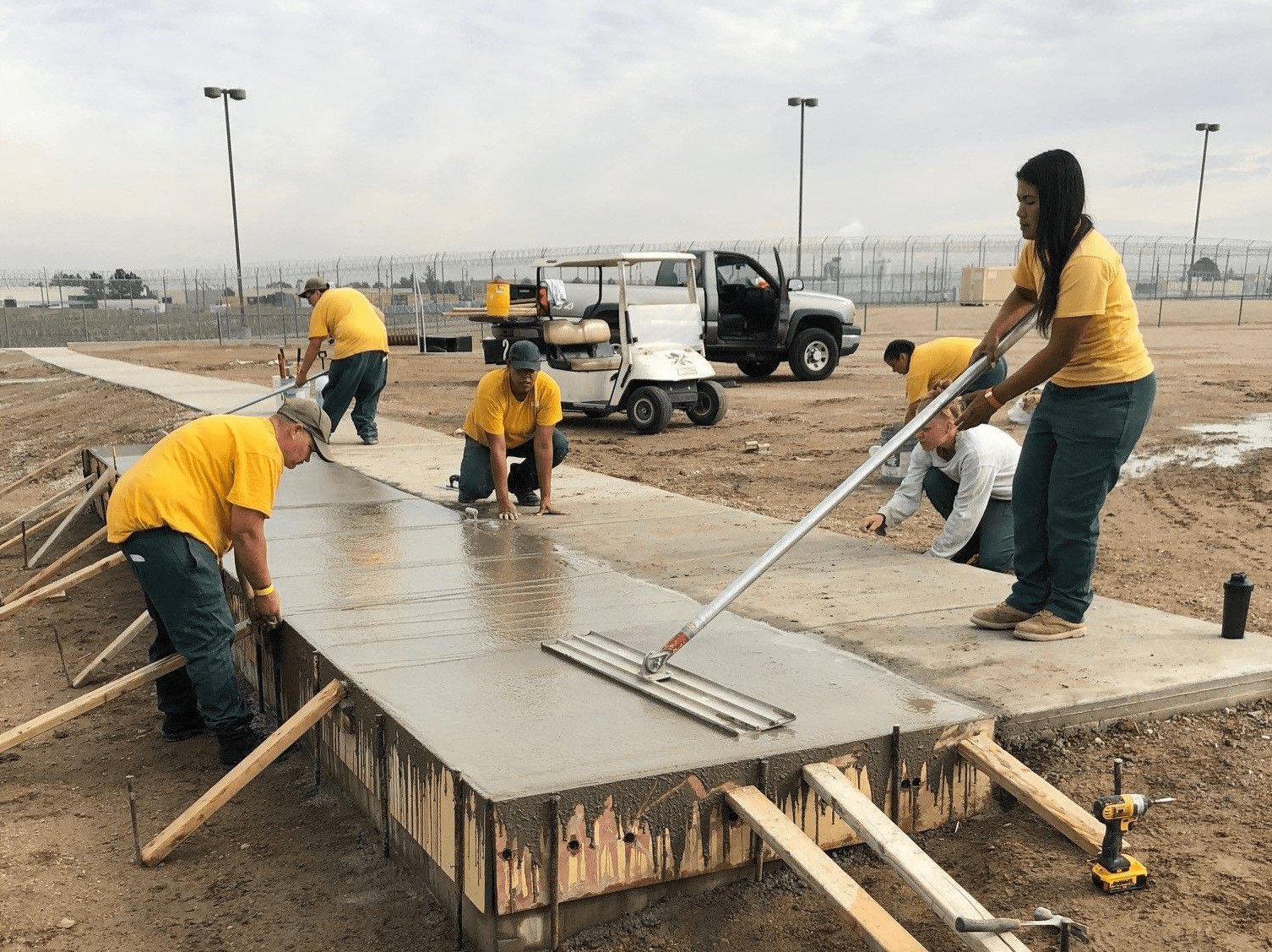

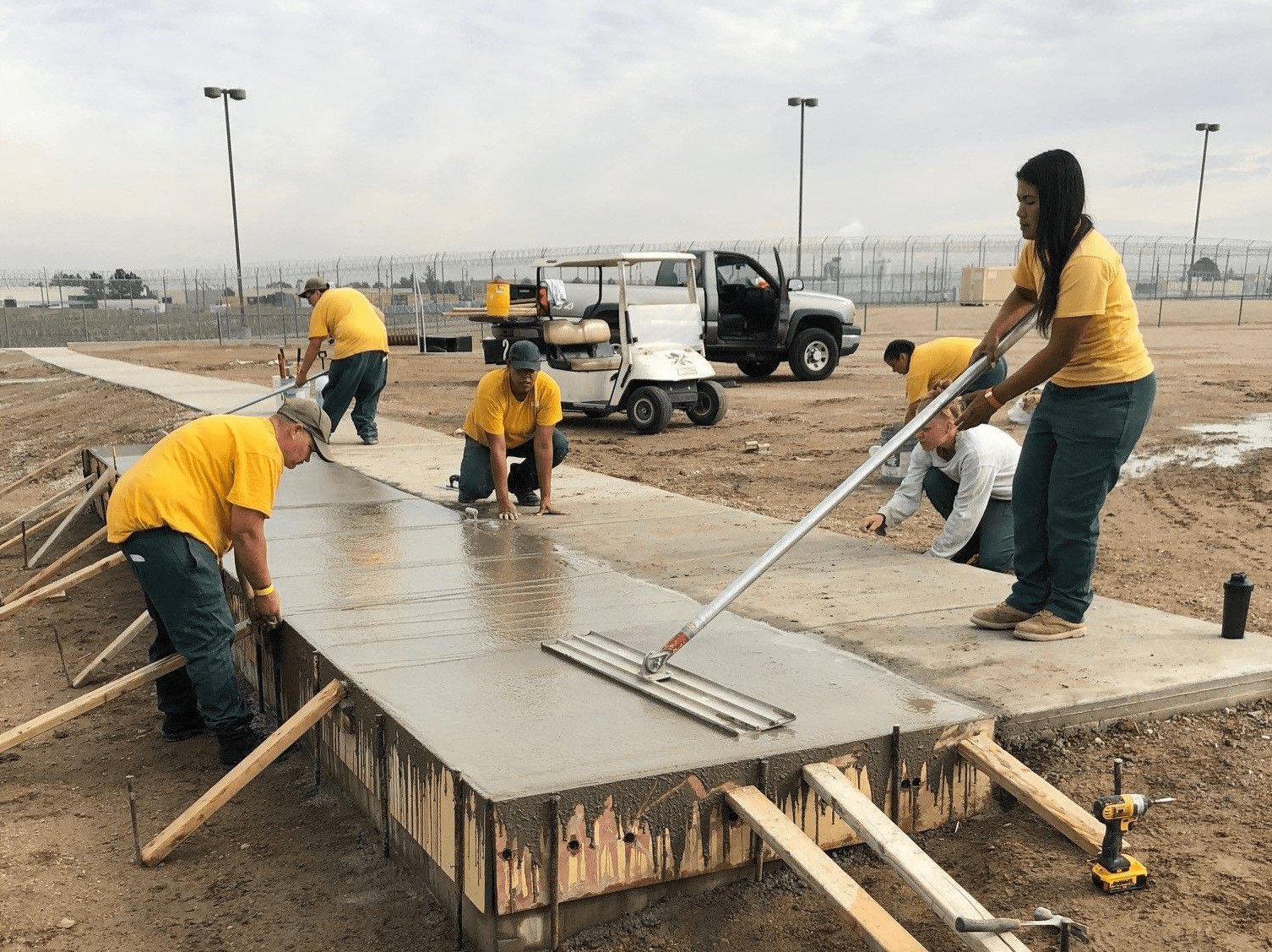

State and local governments rely heavily on incarcerated workers for various needs: highway and road work; cleaning governors and mayoral estates; maintenance of hiking trails; making furniture for state and government buildings, including for public universities; and even doing hospital laundry. Incarcerated workers also conduct vital public services during times of crisis, from fighting wildfires to making personal protective equipment throughout the pandemic.

“It’s a massive labor force that is completely hidden from view,” Gibson-Light told Bolts. “And that’s by design.”

In addition to off-setting costs for federal, state and local governments, approximately 4,100 companies in the U.S. have directly profited off of prison labor, a number that is likely an undercount—including large companies like Walmart, McDonald’s, Starbucks, IBM, Tyson Foods and Microsoft, according to a database created by the advocacy organization Worth Rises.

“A lot of people are making a lot of money off the system,” said Arrington, who has worked for the reentry nonprofit, Second Chance Center, since his release. “It is no different than it was 200 years ago.”

Nationally, the minimum wage for incarcerated workers is anywhere from $0 to 35 cents an hour, according to an ACLU report. Some jobs can pay more than a dollar an hour, but those jobs are rare. The pay for people incarcerated in Colorado prisons ranges from 33 cents to more than $2 an hour for some jobs. At least nine states—Maine, Nevada, Texas, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida—pay incarcerated people nothing for almost all prison jobs.

Gibson-Light says better wages alone don’t address the main problem with prison slavery: forced labor under threat of punishment.

“Had, in the 1800s, Abe Lincoln said, ‘Everyone who was enslaved in the Confederate States shall now be given three cents a day,’ the abolitionists of the time would not have been satisfied,” he said. “There’s a reason it’s the Emancipation Proclamation, not the compensation proclamation. It’s not a question about wages. The question is about freedom.”

Valerie Collins, an attorney with Towards Justice, the nonprofit worker’s rights law firm that is representing the incarcerated workers who sued in Colorado, told the crowd at the Juneteenth event that’s precisely why their case doesn’t make arguments about wages.

“In a lot of ways, that kind of muddies the water,” Collins said. “We did not bring wage claims …to keep the focus on the forced nature of the work itself, in the coercion that is used to extract that labor.”

That strategy differs from the one advocates took in 2020, when four incarcerated people filed a lawsuit against the state contending that the 10 cents an hour they were making amounted to “slave wages.” The men asked for minimum wage and to be considered state employees and receive worker benefits such as sick leave and medical benefits, but a state judge dismissed their claims.

The current lawsuit was filed on behalf of Harold Mortis and Richard Lilgerose, who are both incarcerated at the Fremont Correctional Facility in Canon City. It alleges that the men were disciplined for refusing to work in the prison’s kitchen during the COVID-19 pandemic due to existing physical and mental health conditions. A correctional officer threatened that Mortis would be removed from his incentive living program if he didn’t work in the kitchen, according to the lawsuit. When he refused, they removed two days of his earned time—extending his time in prison. Similarly, Lilgerose lost four days of earned time and was threatened with losing more privileges such as recreation time and visitation for refusing to work.

Colorado Department of Corrections policies state, “All eligible offenders are required to work unless assigned to an approved education or training program.” Consequences for refusing to work can include “restricted privileges, loss of other privileges, delayed parole hearing date, and not being eligible for earned time”—all the things incarcerated people use to “better or maintain your body and your mind,” Gibson-Light said. Attorneys for the state of Colorado have argued that they are “incentivizing work” and not forcing it.

“Many programs provide certified classroom education, apprenticeships, and certificates as well as on-the-job training and experience in a variety of in-demand industries,” a CDOC spokesperson said in a written statement to Bolts. “In addition to technical skills, our programs also teach critical soft skills that help prepare inmates to interact professionally with others in a work setting. These skills help contribute to the successful rehabilitation of inmates.”

State prison systems typically justify forcing people to labor for little to no money under the threat of punishment by claiming the work is rehabilitative. But often, the jobs on the inside don’t translate to opportunities on the outside.

“We’re talking about full internal labor markets with lots of different jobs: stamping license plates, making street signs, cleaning trails, raking rocks, building prison walls, operating call centers, repairing and maintaining vehicles, janitorial work, and anything and everything in between,” Gibson-Light said. “On the surface, it sounds like ‘Oh, there’s so many opportunities.’ (But) they do not align with the realities of the labor market,” he added. “You can be a barber and make good money, but you get out and you can’t get a barber license if you have a record.”

Groups in Colorado first organized and got a constitutional amendment on the ballot in 2016, but it failed by a slim margin, with 50.4 percent of voters choosing to leave the language alone.

“When we woke up to Donald Trump being president, we also woke up and found out that Colorado voted to keep slavery,” Allen recalled.

In 2018, a coalition of organizations tried again, this time putting a bill in front of lawmakers to get it on the ballot. The bill passed unanimously. Then, in preparation for the question going in front of voters, organizers went door to door and held film screenings in churches across the state showing the 2016 documentary “13th” by Ava DuVernay, which explores the historical connection between slavery and mass incarceration.

The 2018 amendment passed overwhelmingly, with 65 percent of voters approving it. Ray, who worked on both amendment campaigns, says the vote, while decisive, still points to a large number of Coloradans willing to tolerate a form of slavery. “Obviously, that goes to show (that) we’ve got some more work to do,” Ray said. “We haven’t all arrived.”

After they won, the calls started to flood in from organizers across the country looking to make the same change in their own states.

Like in Colorado, the push has been an uphill battle for other states. After failing to get lawmakers to put the issue on the ballot in 2021, organizers in Louisiana tried again in 2022 and got a bill through both legislative chambers, setting up a fall referendum. But it ultimately failed.

“People were like, ‘No, slavery was abolished in 1865!’ Meanwhile, I’m over here pickin’ cotton,” said Curtis Davis, the executive director for Decarcerate Louisiana who advocated for the measure by talking about his own experiences while he was incarcerated at the Louisiana State Penitentiary. Davis says he thought he had rights and tried to refuse when he was sent to pick cotton within his first week of being locked up in 1990. “The guy just pointed his shotgun at me,” he recalled. “The guy told me, ‘You gave up your rights when you got convicted.”

Later, Davis says he purposely dropped a weight on his foot so he didn’t have to work 12 hours in the scorching Louisiana sun. As punishment, he recalls being sent to solitary confinement and was written up for “damaging state property.” He says removing the slavery exception is about, “Treating people as people, not property.”

Some of the measure’s champions, including the ACLU of Louisiana and Representative Edmond Jordan, a Baton Rouge Democrat who sponsored the amendment, eventually pulled their support during the 2022 campaign. They said the version that had made it before Louisiana voters was too ambiguous after legislative dealmaking diluted the language. Voters at the ballot box were asked, “Do you support an amendment to prohibit the use of involuntary servitude except as it applies to the otherwise lawful administration of criminal justice?”

In the face of that confusion, the amendment failed by a large margin, 61 to 39 percent.

During the 2023 legislative session, a bill to put the amendment on the ballot again this year passed the House but died in the Senate. “We are just keeping on going,” Davis said to Bolts. “We are like that little energizer bunny.”

Even if voters in more states pass constitutional amendments that end the exception for prison slavery, Gibson-Light says that elected leaders and officials across all levels of government have an incentive to oppose meaningful changes to prison labor.

“If (incarcerated workers) were regarded and protected and compensated like real workers, which they are, the state would go bankrupt,” he added. “And I think that’s an important part of the underlying story.”

In October 2022, a state district judge hearing the lawsuit over forced labor in Colorado prisons ruled that the threat of isolation or physical punishment could be deemed unconstitutional, but also concluded that CDOC’s practice of taking away privileges such as good time may be allowable, according to 9News. The lawsuit is still pending.

Advocates who pushed to end the slavery exception say they are looking for other ways to improve prison work conditions that go beyond giving incarcerated people the choice of whether to work at all. Ray with Together Colorado says she wants better access to work programs that have connections to employers on the outside; better wages to help incarcerated people support themselves and their families; banning the use of solitary confinement, which has been used to punish people for refusing to work; and giving incarcerated people more worker protections.

“Many of them are up on roofs doing roofing with zero experience,” she added. “We are meeting folks who have lost fingers because they’re working on faulty equipment or equipment that they haven’t even been properly trained on.”

Arrington recently earned his aircraft mechanic license from the Federal Aviation Administration—the same one he was studying for when he was wrongly incarcerated. He’s moving out of state with his wife to pursue his career but plans to continue fighting to abolish prison slavery.

For now, Arrington and other organizers in Colorado have turned their attention to Polis, urging him to use his authority to force CDOC to change their policies. Organizers under the unifying title, End Slavery Colorado, asked to meet with the governor to discuss prison slavery last month, but as of this writing, they haven’t heard back. The governor’s office declined a request for comment for this story, citing the pending legislation.

“(Polis) could end it tomorrow,” Arrington told the crowd on Juneteenth. “He could stop fighting slavery in court and actually be accountable for the thing that 65 percent of us told him we wanted to do.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.