In Colorado’s D.A. Races, Disagreements Abound on Criminal Justice Reform

In four populous districts with open prosecutor elections, debates center on issues such as drug policy, jail capacity, and police impunity.

| September 25, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

In four populous districts with open prosecutor elections, the focus is on drug policy, jail capacity, and police impunity.

Since last year, Colorado has adopted a slew of significant criminal justice reforms, from abolishing the death penalty and ending qualified immunity, to curbing the use of cash bail and reducing drug possession charges to the level of a misdemeanor. But as advocates press for next steps to make bigger dents into mass incarceration and racial injustice, the upcoming district attorney elections loom large, given the clout that prosecutors tend to have in statewide debates.

DAs also enact these new laws and have ample discretion to go further in implementing reforms.

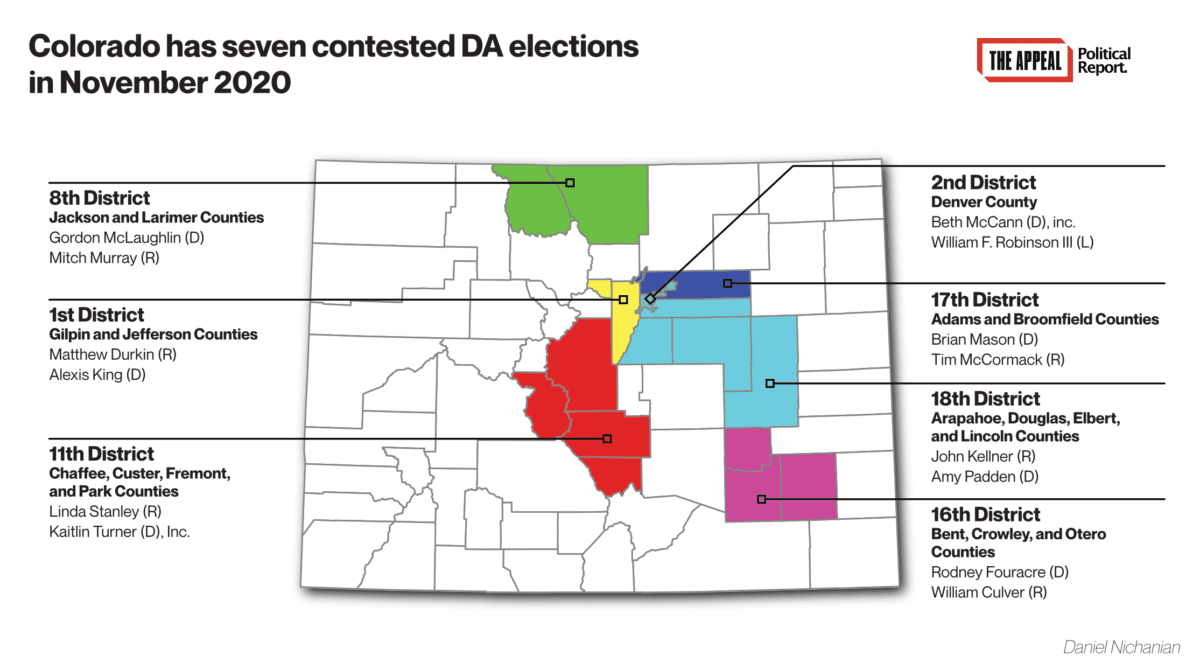

All 22 of Colorado’s DAs are up for election this year, but most of November’s races feature just one candidate running unopposed.

But in the four populous jurisdictions that are anchored around Adams, Arapahoe, Jefferson, and Larimer counties—districts ranging from 360,000 to more than one million residents—the incumbents are term-limited and retiring, triggering wide- open scrambles in the general election.

Big contrasts have emerged across some of these elections on issues such as drug policy, jail capacity, and the death penalty. Compared with the country’s most progressive DA candidates this year, some of the Colorado contenders running on reform platforms are relatively cautious. Still, the results may lead to significant change in their district’s court systems.

In the 18th District, a prominent champion of the death penalty and of life without parole could be replaced by a candidate who wants the state to decrease the frequency of life sentences. Elsewhere, in Jefferson County, a candidate wants to stop prosecuting simple drug possession cases and to divert defendants without burdening them with a criminal conviction.

Below we delve into these four elections, exploring each through the lens of one dominant policy area.

1st District | Jefferson and Gilpin counties

Candidates: Republican Matthew Durkin and Democrat Alexis King

Context: DA Peter Weir, a Republican, is retiring in a district that Hillary Clinton carried by seven percentage points in the 2016 presidential election.

A lead issue: Drug policy and diversion

The DA candidates in this jurisdiction of nearly 600,000 people are worlds apart on whether Colorado should continue the practices associated with the war on drugs.

Durkin, now the chief deputy DA, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. But he has staunchly argued against reform. “An effort to minimize or eliminate drug penalties enables further addiction,” he writes on his website. Studies dispute the view that punitive policies have a deterrent effect on drug use, however. He has also denounced the new Colorado law that reduces simple possession of most drugs to the level of a misdemeanor.

King, who is a former deputy DA herself, told The Appeal: Political Report that Colorado still has more work to do to “minimize the criminalization of addiction.” Cases of simple drug possession would be better handled through public health services, she said.

“The criminal justice system has become the catchment basin for public health issues, and addiction is probably the main one,” she said.

She added that she “can commit” to not prosecuting simple drug possession cases where there is no other alleged offense in order “to keep them actually out of the criminal justice system,” but that her office would keep playing a role “to connect them with services … so that they can hopefully maintain any housing, employment and transportation that they already have.” She would adopt a similar approach, she added, with “survival” cases that are tied to poverty, such as petty theft.

A related issue in this race is how the DA’s office should divert people toward programs that are meant to serve as alternatives to incarceration.

King says the district should stop requiring that people plead guilty in order to participate in diversion programs because the goal should be to steer them clear of criminal convictions, rather than only avoiding jail sentences.

“The destabilization that comes with jail, bond, court appearances, can actually really set people up for failure,” she said, calling for “true diversion” policies that give people charged with “low level” offenses “a path to stand back up in the community without having to go to the courthouse doors.”

Durkin did not respond to a question on whether he thinks a plea should be a condition for access to diversion, but a Denver Post article inferred this is a point of contrast between the candidates

8th District | Jackson and Larimer counties

Candidates: Democrat Gordon McLaughlin and Republican Mitch Murray

Context: DA Cliff Riedel, a Republican, is retiring in a district that Clinton carried by four percentage points in the 2016 presidential election.

A lead issue: Jail space and pretrial detention

Larimer County (Fort Collins) is spending $75 million on a project that will expand the jail by 250 beds. Critics say the county should instead be dealing with overcrowding by shrinking the jail population, a demand that echoes activism against jail expansions elsewhere in the country.

The candidates running for DA, a position with direct influence on the jail population, are on opposite sides of this issue. Murray, the chief assistant DA, approves of the jail expansion. He told the Political Report that it is needed to “accommodate future beds, due to our ever increasing population” as well as to “bring our jail in line with modern criminal correction practices” to ensure “the safety and well-being” of detainees and staff.

But McLaughlin, a former deputy DA, opposes it. Money should be spent on measures like “substance abuse and mental health treatment,” he told the Political Report, rather than “simply expanding our ability to warehouse folks who cannot post their bond.” And he faults the DA’s office for not identifying “alternatives to incarceration to lessen the need.”

When it comes to specific policies to shrink the jail, though, the candidates gave mostly similar answers, diverging on some key details.

Both expressed support for diverting some simple drug possession cases, but not as a blanket policy—a far cry from the position of some progressive DAs that no simple possession cases should be criminally prosecuted. On pretrial detention, neither favor ending the use of cash bail altogether, though McLaughlin argued that a defendant’s ability to pay should be better taken into account than it is currently. Asked about state legislation filed this year to curb cash bail for misdemeanors and low-level felonies, they were both broadly supportive of the provision that would limit the use of cash bail to cases where courts decide the defendant poses a safety risk. Murray took issue with other provisions in that bill that restrict judges from imposing nonmonetary conditions (like limiting alcohol use) “for the good of the defendant.”

17th District | Adams and Broomfield counties

Candidates: Democrat Brian Mason and Republican Tim McCormack

Context: DA Dave Young, a Democrat, is retiring in a district that Clinton carried by nine percentage points in the 2016 presidential election.

A lead issue: Police accountability and impunity

The death of Elijah McClain, a Black man who went into cardiac arrest after being put in a chokehold by the Aurora police and later died, shaped Colorado’s debates on policing over the past year and helped drive the state to adopt one of the nation’s furthest-reaching reform packages in June.

Young, the incumbent, announced soon after McClain’s death that he would file no criminal charges against the officers involved. The attorney general’s office is now reviewing the case to determine whether prosecution may be warranted.

But these dramatic circumstances have not come to define the election to replace Young. Neither of the candidates are willing to discuss the specifics of the case and what, if anything, they would have done differently during it. And neither embraces the stronger accountability policies that many advocates are demanding this summer.

Brian Mason, a deputy DA, told the Political Report that McClain’s death “is a tragedy” but that he could not comment on its legal details as it is a “pending case.” It speaks to “police brutality and overincarceration of Black and brown people,” he added, and said he would “vigorously investigate” future allegations of police misconduct or excessive force.

He did not commit to supporting a civilian review board with subpoena power, nor to transferring cases of police brutality to the attorney general’s office or an outside prosecutor. He said he was cautiously “open” to such transfers, but indicated his plan is to have them investigated by a “multi-agency team,” including the local DA’s office, so as to not rely on internal police inquiries. He also did not express support for maintaining a public “do not call” list of officers with a history of misconduct who he would pledge to not rely on for testimony—a promise that defined New York’s DA elections in June—and said he preferred current practices of disclosing such background to defense lawyers in the course of proceeding with a case.

Mason also expressed concern about Colorado’s decision to end the qualified immunity defense for police officers in state courts, saying it would hinder recruitment. But he stressed that he was supportive of the rest of the package of reforms adopted by the legislature this summer.

McCormack, who works as a deputy prosecutor in another district, has been endorsed by the Colorado Fraternal Order of Police and by local police unions.

He did not answer multiple requests for comment on how he would approach matters relating to police accountability, such as a “do not call” list. He, like Mason, told the Denver Post he would not discuss the specific case of Elijah McClain.

18th District | Arapahoe, Douglas, Elbert, and Lincoln counties

Candidates: Republican John Kellner and Democrat Amy Padden

Context: DA George Brauchler, a Republican, is retiring in a district that split almost evenly in the 2016 presidential election.

Lead issue: The death penalty and life sentences

Colorado has repealed the death penalty and life without parole for children, and is now debating more proposals to make life sentences less common. (The share of people in Colorado prisons serving life without parole is higher than in most neighboring states.)

George Brauchler, the DA of the 18th District, a very populous jurisdiction that is home to more than 1 in 6 Colorado residents, did his best to stand in the way of these reforms.

He is known for, as the ACLU of Colorado put it in 2018, a “devotion” to capital punishment, as well as for fighting efforts to end juvenile life without parole. This year, he is speaking up against a proposed bill that would reclassify “felony murder”—a category used to charge people with a murder they themselves did not commit—so that it no longer triggers life without parole. (In 2018, California adopted a bill that limited the felony murder doctrine altogether.) Despite this brand of punitive politics, or perhaps because of it, Brauchler made news this week for choosing to not charge a driver who sped through a crowd of Black Lives Matter protesters.

Brauchler is a prominent figure in Colorado who ran for attorney general in 2018, so the race to replace him could be a tremendous shift in statewide politics by flipping the lobbying priorities of one of Colorado’s most populous districts.

Amy Padden, the Democratic nominee, has different values than Brauchler on these issues. She is supportive of the death penalty’s repeal, as well as the end of life without parole sentences for minors.

And she told the Political Report that more reform is needed. There are “too many life sentences” in Colorado, she said, though she would not favor ending all life without parole sentences. Padden, who is now a deputy DA in a different district as well as a former federal prosecutor, would also review current practices for possible patterns of “overcharging.” And she supports the proposed “felony murder” bill. She would also favor narrowing the definition of “felony murder” to cases where the defendant is found to have exhibited some intentional or reckless behavior.

John Kellner, the Republican nominee and a deputy DA who works alongside Brauchler, did not answer multiple requests for comment on his positions on the death penalty and life sentences; he has also not responded to policy questionnaires prepared by other organizations. Some of his social media posts signal positions similar to the current DA, for instance on the death penalty.

Padden, who landed an endorsement from U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, has prioritized expanding diversion programs for lower-level offenses. “We know that prison sentences focus on punishment rather than rehabilitation,” she said, whereas “alternatives to incarceration, like diversion, make our communities safer because they reduce our crime rates” by “helping people turn their lives around.”

What is happening in the rest of Colorado?

Two other districts, both much less populous, feature contests between major party candidates. In the 11th (Chaffee, Custer, Fremont, and Park counties), appointed Democratic DA Kaitlin Turner faces Republican Linda Stanley. In the open 16th (Bent, Crowley, and Otero counties), Republican William Culver and Democrat Rodney Fouracre face off. And Denver’s Democratic DA Beth McCann faces Libertarian candidate William Robinson III.

Candidates are running unopposed in 15 districts, including DA Michael Dougherty in Boulder County and newcomer Michael Allen in El Paso and Teller counties.

A lesser-known candidate with no November rival is Alonzo Payne, a progressive who ousted an incumbent in the 12th District’s primary, which includes rural counties in the San Luis Valley. Payne ran on making the case that Colorado needs better economic justice policies to curb mass incarceration. “If you’re not looking at the seeds that cause the problem, you’re always gonna have wheat,” he said in July. Now he wants to bring criminal justice reform to rural areas.

“We can get it done because we agree that people should be treated fairly regardless of their socioeconomic status, and maybe we do teach the liberal bastions how things can be done by these country bumpkins over here,” he said.