Colorado Adopts First-in-Nation Mandate for Voting Centers in Jails

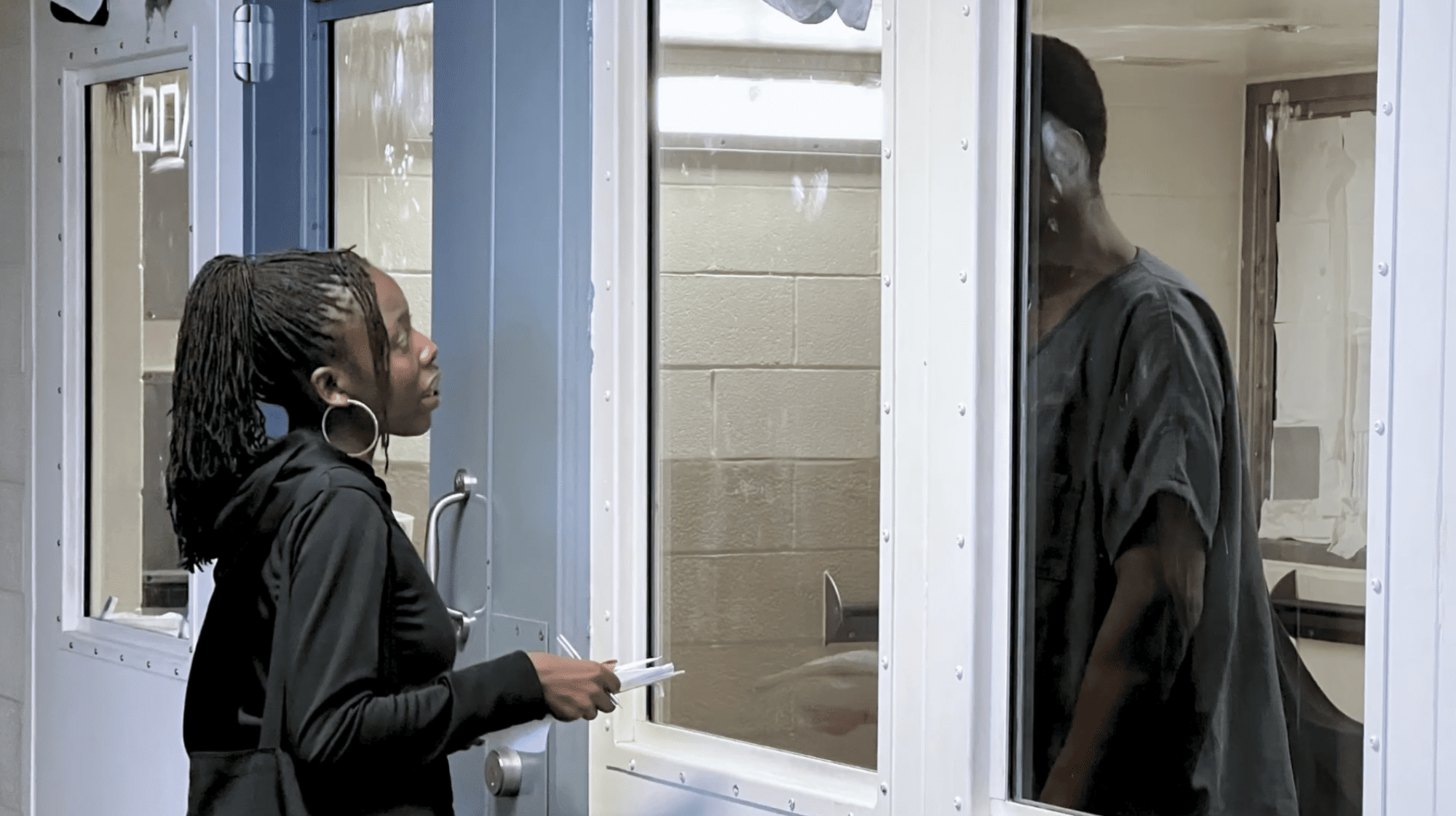

People held in county jails typically retain the right to vote but face enormous hurdles to actually casting a ballot. Lawmakers passed a bill meant to remedy the issue.

| May 8, 2024

Editor’s note: Colorado Governor Jared Polis signed this bill into law on Friday, May 31, 2024. Bolts reported on the effects of the reform in March 2025.

Scott Deno, who oversees Colorado’s largest jail, says he takes seriously his role in helping people vote if an election rolls around while they’re under his custody. His jail, in Colorado Springs, holds more than 1,600 people on any given day, and most are being held pretrial or serving out a misdemeanor sentence, meaning that they retain the right to vote.

Testifying in February before a legislative committee, the chief of detention for El Paso County’s sheriff’s office told lawmakers he was “very proud” of his record on this front. “I can say with 100 percent confidence: if an incarcerated citizen is residing in the El Paso County Jail during the election season, they will have the opportunity to cast their vote in a secure and timely manner,” Deno said.

State Senator Tom Sullivan followed up a bit later in the committee hearing: “How many of the incarcerated people that you had actually voted in the last election?”

Steve Schleiker, El Paso County’s clerk and top elections official, a Republican who was testifying alongside Deno, took that question.

“Zero,” he said.

Amanda Gonzalez, the Jefferson County clerk, was present at the hearing for that admission. “It was a wild moment,” she told Bolts. “You could feel it in the room.”

El Paso County is no outlier. A statewide review by the nonprofit Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition found that in the 2022 general election, only 231 people voted from the state’s jails. Some 6,000 people are held in jails across Colorado every day, a population that’s disproportionately Black and Latinx.

Gonzalez, a Democrat, said she has talked to sheriffs who run these lock-ups but dismiss these numbers. “To me, this is just a civil rights issue,” she added. Like their counterparts around the country, Colorado sheriffs have substantial power over whether the people in their custody get to exercise their right to vote. Sheriffs decide whether to allow outside groups, like the League of Women Voters, inside jails to assist people in registering to vote or obtaining a ballot. They control the flow of mail in and out of jails. They also control the flow of information relevant to voting; formerly incarcerated people in Colorado and other states have told Bolts that they never were notified of their voting options while they were jailed.

The Colorado legislature on Friday adopted a first-in-the-nation reform last week to fix this. Senate Bill 72, which now awaits the signature of Governor Jared Polis to become law, would give people held in local jails a lot more opportunities to obtain and cast a ballot.

It would require that sheriffs establish polling stations within local jails across Colorado each general election to operate for at least one six-hour period. It would also require every jail to designate a ballot drop-off location, for those who want to vote by mail.

Colorado would be the first state to enact a mandate of this sort. Nevada, Massachusetts, and Washington state have recently passed initiatives meant to make jail voting easier, but none feature the central requirement of Colorado’s: turning local jails into in-person polling places.

“It’s really a gold standard for what all states can aspire to,” Carmen López, an expert on jail voting for The Sentencing Project, a national research and advocacy organization, told Bolts. “Folks in Colorado who are in jails will have the voting experience that the rest of society in Colorado has. I think that’s really important.”

SB 72 builds on recent efforts in Denver, where local officials set up in-person voting from jail starting in 2020, to great effect so far: The jail’s turnout rate has occasionally surpassed the city’s overall rate. Elections workers and outside voter-engagement groups have also been able to enter the Denver jail to register people to vote and help them access ballots.

Just a few cities outside of Colorado, including Chicago and Dallas, have set up similar programs for jail voting.

The reform does not affect who is already eligible to vote. Colorado, like nearly every other state, bars people from voting while they are incarcerated if they’ve been convicted of a felony, and SB 72 keeps it that way. Rather, the bill seeks to improve ballot access for a group of people who already have the right to vote but face major barriers to actually using it.

Should Polis sign SB 72 into law, it’ll go into effect in time for this November’s election. (A spokesperson for the governor’s office declined to tell Bolts whether Polis, a Democrat, would sign the bill. Several people who’ve worked closely on it said they expect he will.) This bill would not apply to primary elections; its proponents say they hope to expand it in the future.

This bill sailed through both the House and Senate. It received broad support from Democratic lawmakers who run both chambers, and it also garnered some Republican votes.

But Colorado’s county sheriffs largely opposed the legislation, and their statewide association lobbied against it. Some county clerks, the local officials who oversee local election administration, also resisted the reform. During Colorado’s 120-day legislative session, which ends on Wednesday, a parade of local officials from all parts of the state asked lawmakers to reject, or at least neuter, SB 72.

“We already serve this voting group,” testified Sheri Davis, the Republican clerk in suburban Douglas County.

“What we are currently doing across the state works,” said Democratic Sheriff David Lucero of Pueblo County, not far from Colorado Springs. “I would ask you to vote ‘no’ on this.”

Shannon Bird, one of the few Democratic lawmakers who voted against the measure, pointed to local sheriffs’ opposition to explain her stance. “They were concerned that their jails did not have the appropriate infrastructure to support the requirements of the bill; they were worried about jail staff’s ability to ensure the safety and security of inmates and election staff during the voting process,” she told Bolts. She also echoed many sheriffs’ point that there’s just no problem to begin with. “All sheriffs I heard from made clear that individuals in their custody have a right, and are already able, to vote safely through Colorado’s mail ballot process,” she said.

Some local opponents of the bill also said it would demand too much of their offices, which in many cases are short-staffed. Schleiker told lawmakers the bill would be enormously expensive to implement; El Paso County spends $26 per voter during a typical election, he said, but would have to spend more than $2,000 per jailed voter, under SB 72’s requirements.

Proponents of SB 72 countered during the hearings that this would be neither expensive nor burdensome, and that, in any event, sheriffs must learn to see voter access as mandatory.

“This is not a favor we’d be doing for these citizens,” Colorado voting rights advocate Stephanie Puello told lawmakers in the February hearing. “This is a right that they are entitled to.”

Gonzalez, the Jefferson County clerk, estimates it would cost her county about $1,400 in total to implement SB 72, a far cry from the $2,000 per-voter price tag Schleiker predicted.

SB 72’s backers say they’ll closely monitor its rollout, given the lack of buy-in from many of the people who run Colorado’s local lock-ups and elections offices. Kyle Giddings, a civic engagement advocate for the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition who is himself formerly incarcerated, told Bolts that he is helping to gather a group of volunteers who can provide staffing and resources to any jail administration that is struggling to adjust to the reform, or is simply unmotivated to meet its demands.

“That starts on Day One,” Giddings said. “We’ve already had conversations with sheriffs that are very vocally against this bill, to say that after this bill passes we’re not going to disappear into the wind and hope they do their job. We’re going to be there the whole ride.”

Giddings and others said they intend to watchdog every jail in the state to make sure that eligible voters are granted meaningful ballot access. They intend to maintain regular communication with sheriffs and clerks to make sure those officials understand and respect the demands of SB 72; they also point toward the bill’s requirement that the secretary of state’s office provide training materials to local officials.

Tova Wang, a senior researcher of democratic practice at Harvard University, told Bolts that she’s hopeful SB 72 has sufficient teeth to force even the most reluctant county officials to make voting from jail much easier.

“You can’t legislate motives, but you can legislate participation,” she said. “This is not that hard to do. It is sometimes the first time you do it, but after you’ve done it once, it’s not a huge lift. These concerns about resources and security—there have been a number of places able to address those challenges successfully. Denver has been doing it for a while now.”

Gonzalez, the Jefferson County clerk, says she has found that it doesn’t take much effort to bring turnout up in jails, especially when the baseline leaves so much room for improvement. When she ran for office, she said, she was “horrified” to learn about the virtually non-existent voter engagement program in her county jail: in a facility that holds about 1,000 people, she said, only three cast ballots in November of 2022.

It’s not hard to see why that number was so low, she said, explaining that jail staff was not making much effort to publicize voting rights information.

“In Jefferson County,” she told Bolts, “the process was that there was just one sign posted with information. So a person would have to see the sign, want to vote enough to go to a deputy and ask for a voter registration form, then fill out that form. The deputy turns the form into the clerk’s office, the clerk’s office would generate a ballot, and get it to the voter. There are several barriers there where that would be a system that would not work for incarcerated voters.”

Led by Gonzalez, Jefferson County’s elections office partnered with the jail to make relatively inexpensive tweaks—creating a hotline that incarcerated people could call for free to ask about voting; advertising elections information inside the jail; and going cell-by-cell to offer voter registration forms, among other actions. About 100 jailed voters participated in Colorado’s presidential primary earlier this year, a large increase from the three who voted in 2022.

One hundred people voting from Jefferson County’s jail still amounts to low turnout, and Gonzalez, who testified in favor of SB 72 at a House hearing, said she’s hopeful her county can keep improving. Under the bill, clerks like her would be able to supplement existing mail-voting efforts with the option for convenient, in-person voting.

Colorado allows same-day voter registration, so Gonzalez says the physical voting centers could even grow voter rolls.

But she said the best version of this reform will need real buy-in from sheriffs—something she has struggled to find in her own county. She questioned why so many sheriffs and clerks around the state are so unbothered by the fact that hardly anyone in Colorado is voting from jail.

“If you told me we had some precincts [outside of jail] with turnout rates of less than 1 percent, I’d be screaming at the top of my lungs about what is going on there,” Gonzalez said. “But our system has, unfortunately, a really long history of not including people of color, low-income people, and people involved in our criminal justice system. That’s exactly what we’re trying to fix. I don’t want those people ignored.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.