Efforts to Expand Ballot Access in Washington State Jails Face Local Pushback

Only a handful of counties applied for new state funding to ensure eligible voters aren’t disenfranchised in county lockups, while some local officials actively blocked such attempts.

Khawla Nakua | January 23, 2023

Last year, the Washington State legislature allocated $2.5 million for grants to counties wishing to ease ballot access to a group of people who are eligible to vote but routinely unable to do so: people locked inside county jails. Most people in jail have not lost the right to vote because they are held pretrial or because they have a low-level conviction, but they are often denied ballots or even any information they would need to know how to request one.

Yet only five of Washington State’s 39 counties applied for that money, according to the Washington secretary of state’s office. And some local officials who blocked their counties from participating have been open that they don’t want to help people in jail participate in elections even though they remain eligible to vote.

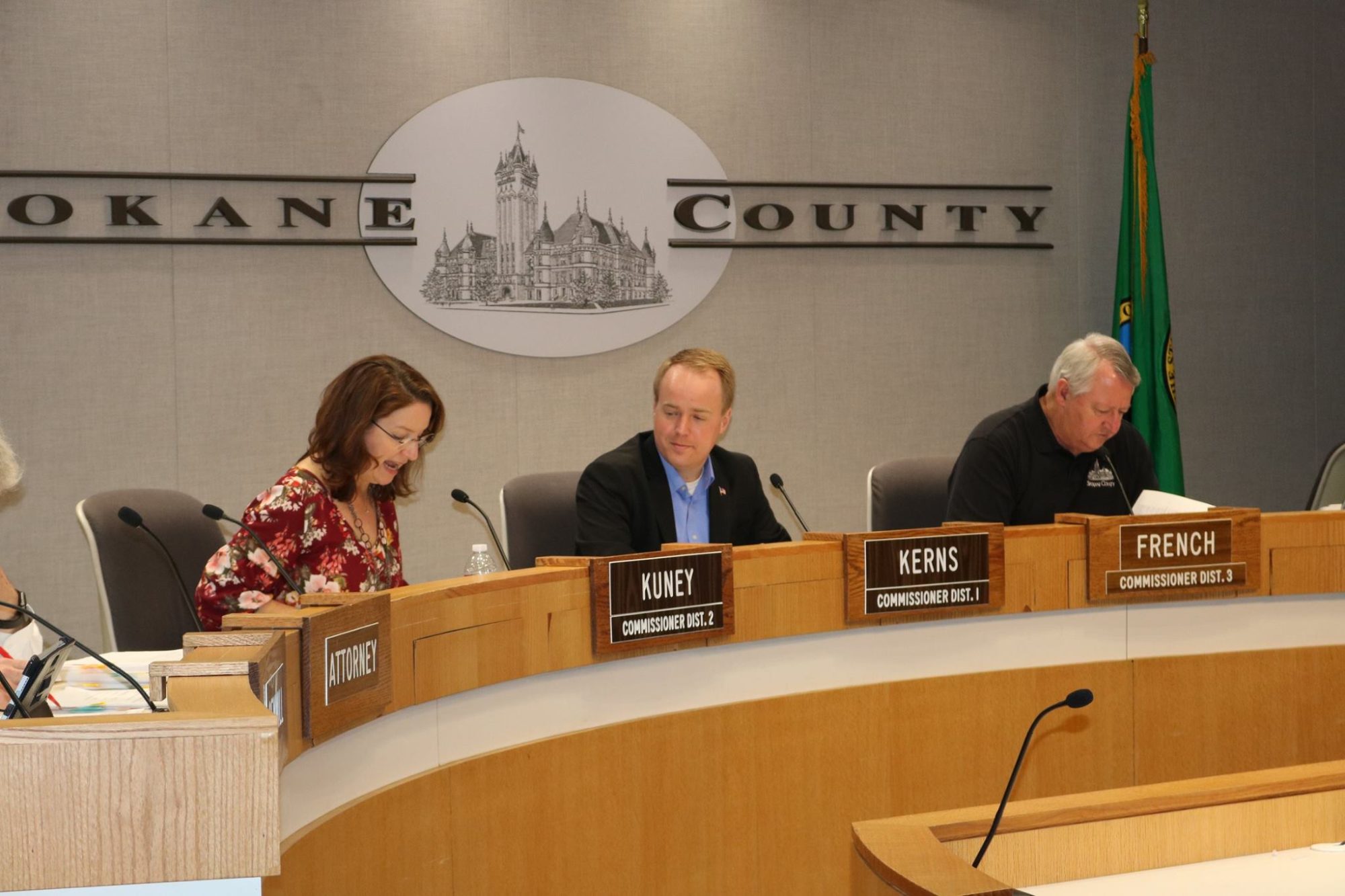

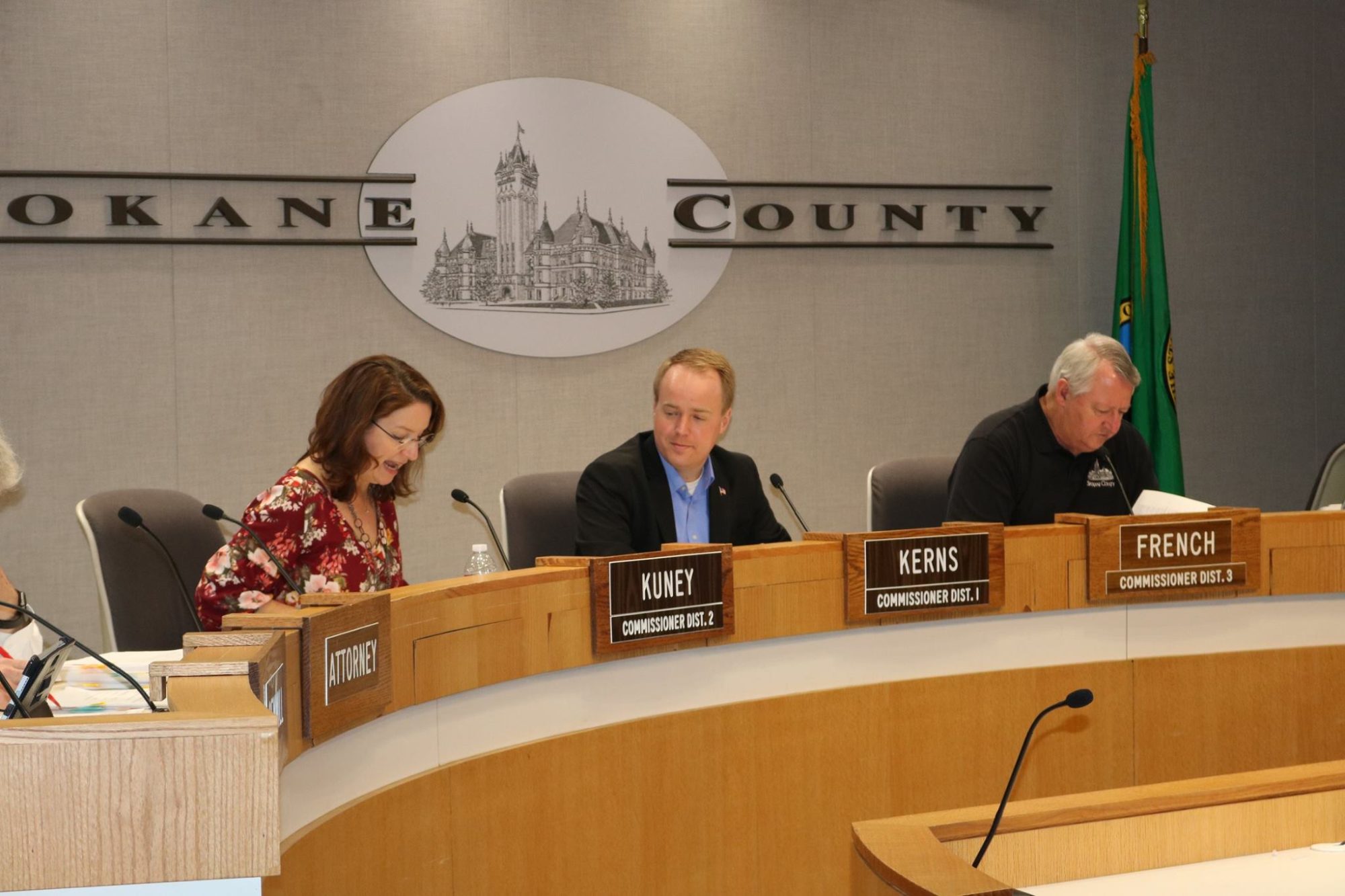

Last September, Spokane County Auditor Vicky Dalton went to the county board of commissioners with her plan to increase voter registration and participation for people incarcerated in the county’s two detention centers. Dalton, the chief local elections official and the only Democrat elected to countywide office in Spokane, said she’d been working with detention staff to improve ballot access in the jails. But Dalton needed the all-Republican board to apply for the newly created state grant to help her office cover the cost of training more jail staff on election procedures, making informational videos to show behind bars, and printing voter guides explaining how to register and ask for ballots while in lockup. (While auditors are their counties’ chief election officials, county commissioners still hold the purse strings and determine budgets.)

The county’s commissioners, wary of more people voting behind bars, rejected her proposal. “So, if you’re a candidate that’s campaigning on a position of being tough on crime, obviously you’re not going to get a lot of votes out of the jail, and the inverse of that also could apply,” Commissioner Al French said during the meeting.

Dalton responded, “We don’t speculate how people vote, we just need to make sure that they have the opportunity to register to receive a ballot and return that ballot.”

In an interview with Bolts, French reiterated his opposition to measures that would make it easier for eligible voters to cast ballots from jail, arguing it “stacks the deck.”

“We want to have a fair and open election, and to try and get voters who have a predisposition, it’s not in my mind consistent with free and open elections,” French said.

The opposition from Spokane officials is in stark contrast to larger trends in the state to reduce the disenfranchisement of people entangled in the criminal legal system. In 2021, Governor Jay Inslee signed a bill, which was sponsored by Tarra Simmons, a formerly incarcerated lawmaker, restoring the right to vote for Washingtonians convicted of felonies automatically upon their release from prison—giving an estimated 20,000 people back their right to vote. Last year, Inslee proposed a state budget that allocated $628,000 to improve voter awareness, registration and turnout in county jails; the final budget that lawmakers passed quadrupled the amount available to counties.

The program left it up to Washington State counties to apply for the funds, though. Other states have adopted stronger approaches to strengthening voting access; Massachusetts adopted a law last year that imposes new requirements on sheriffs and county officials to provide information and ballots to people in jail.

The handful of Washington counties that participated only tapped about $250,000 of the $2.5 million that the state allocated as of this month , according to the secretary of state’s office, with the bulk going to King and Pierce counties, the most populous in the state (each received about $100,000). Counties that have participated—which so far also include Thurston, Benton and Kitsap counties—must submit a report to the state by February detailing how the funds were used and how turnout was impacted, but there are already signs of improvement.

Thurston County Auditor Mary Hall told Bolts that ballots cast from the jail spiked from just three in previous elections to 40 this past November after her office used the $42,000 to hire more staff to help train detention officials and distribute voter guides inside the jail. “It was fantastic,” Hall told Bolts. “We partnered with our jails and they were cooperative despite a covid outbreak and being short staffed, and we ended up hiring some off duty sheriffs to help us make this effort.”

The Washington State legislature could pass yet more measures this year to increase ballot access in county jails. Last week, Simmons filed House Bill 1174, which would require jails to provide incarcerated people information on voter registration and requesting a ballot at least 18 days before an election. The bill would also require each county auditor’s office to create a jail voting plan in coordination with the secretary of state’s office, which could encourage more counties to apply for the funding lawmakers have already earmarked for that purpose.

“All too often those with mental health issues find themselves housed in our county jails. Our cash bail system also means that lower-income people are more likely to spend a significant amount of time in jail. We should not be writing these Americans off,” Simmons said in her statement. “My bill will require that county auditors make an effort to ensure that everyone in their county legally able to vote has that opportunity. Innocent until proven guilty is the basis of our criminal legal system. This bill simply asks that we live those values and protect the right to vote.”

Megan Pirie, co-founder of the Eastern Washington chapter of All of Us of None of Us, an organization that advocates for incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people, said being in jail presents numerous barriers to voting, including the limited availability of outside information like the elections calendar and details about candidates. Even if people know they’re eligible to vote, they might not know how to register or ask for a ballot behind bars (currently, people in Spokane County jails must request forms through the commissary).

Pirie said Spokane activists asked but haven’t been allowed inside to help jail staff register and distribute forms ahead of elections. “We were willing to come in after hours, after people were done with court and register people to vote and were flat out told no,” she told Bolts.

Asked about activists’ complaints, Dalton said allowing people from the outside to enter the jail to help facilitate ballot access would be a “bottleneck for providing voter services directly to the inmates.”

Activists also point to research showing that Black, Native American and Hispanic people are jailed at higher rates and for longer periods than white people in the local jails. “The ability to vote and engage in society that you did not necessarily feel that you belonged just carries 10,000 miles of value,” says Kurtis Robinson, vice president of the Spokane branch of the NAACP. “It is a real core underlying issue surrounding the issue of justice involvement. You cannot understand the importance of it and what it means when it’s not supported.”

During the meeting last September, Dalton told the Spokane commissioners that beyond creating more voter education materials for the jail and working more closely with detention staff, she hoped to survey the jails to see how many of the roughly 700 people locked inside at any given time are eligible to vote. Many likely are: studies in recent years have shown 70 percent of people in Spokane County jails are pretrial detainees who haven’t been convicted.

Dalton urged the commissioners to help her establish new processes around jail voting before the legislature ultimately forces them onto counties. Michael Sparber, the director of the county’s detention facilities, even assured commissioners the new efforts wouldn’t strain his department, saying, “I don’t anticipate it will cause a lot of manpower issues or even a dramatic amount of overtime at the jail.”

But the commissioners weren’t swayed. “Haven’t you come to us and said you’re short on employees? Is this a good use of existing employees and time to go and sort of try to shave votes from the jail?” commissioner Josh Kerns asked Dalton. “I have concerns with this,” Kerns said after he finished questioning her. “I’m not sold on it. I don’t like it.”

Dalton said she would keep working within her existing budget to expand ballot access in the county’s jails and hopes the recent dramatic shakeup of the Spokane County commission could lead to more support for the kind of voter outreach program in the jail that she wanted to launch last year; a change in state law grew the commission from three to five seats last year, and in November voters elected two new Democratic commissioners.

“It’s disappointing but it’s just a small setback,” Dalton said of the county’s refusal to apply for the state grant. “My office and the jail staff will continue to work together to do whatever we can to support incarcerated folks with their right to vote. It may not be as extensive as other counties but we will do what we can.”