The Michigan Jail that Candidates Keep Visiting

This county lockup in Flint goes far beyond most in promoting civic engagement. But the jail still cuts people off from the world in many other ways while they await trial, sometimes for years.

| November 26, 2024

The forum in downtown Flint, Michigan, on the warm early afternoon of Oct. 3, was in many ways a typical election-season scene. A handful of politicians—in this case, candidates for seats on the Michigan Supreme Court and Michigan Court of Appeals—had arrived, some flanked by young staffers, all toting stacks of glossy campaign flyers. One by one, the candidates stood at a lectern to deliver well-practiced stump speeches to several dozen voters who had gathered in a large room on makeshift bleachers and plastic chairs. They offered short biographies, argued that their work and life experiences qualified them for the bench, and asked the crowd to remember their names when voting.

But, for all its familiar trappings, this event was quite a rarity, because it took place inside the county jail, with candidates appealing to an audience of incarcerated people.

“You’re going to go back home one day,” Clerk Domonique Clemons, the top elections official in Genesee County, told the crowd at the start of the forum. “If you want roads that you can drive on, you want a community that has trash that gets picked up, you want a community with good schools—that all comes down to that one vote.”

More than half a million people in the U.S. are held in local jails on any given day, and, unlike people held in state prisons, most are awaiting trial and remain eligible to vote. Yet they are hardly ever included in the democratic process, let alone part of forums like this one.

People in jails are largely cut off from voter information. They seldom exercise the right to vote because actually casting a ballot from any of the roughly 3,000 jails across the country is usually an enormous struggle, if not practically impossible. This is due in major part to general indifference, and sometimes even outright resistance, from local officials and sheriffs who oversee county jails and control ballot access for people in custody.

The candidate forum inside the Genesee County jail in Flint stood out in comparison. Outside advocates had worked for years to persuade local officials to boost civic engagement and voter registration for the more than 500 people detained there daily, and they’ve gotten Chris Swanson, the elected sheriff in Genesee County, to partner with them. In 2022, Swanson hired two formerly incarcerated organizers who circulate information about elections and voting to people detained inside, help them register and cast ballots, and plan candidate forums.

Percy Glover, one of these organizers, had spent time after leaving prison volunteering to boost voter participation at the jail, until he was hired to do this work full-time.

“Without us, people don’t know they can vote, don’t know who they’re voting for, and don’t understand what they’re voting for,” Glover, who was once himself detained in this jail, told me when I visited Flint last month. “My job is to make voting real.”

Oct. 3 marked at least the tenth forum inside the jail since 2021; prior events here have featured candidates for mayor, city council, school board, and Congress.

Ahead of the October forum, Swanson pulled visitors into a side room where he explained how civic engagement for those in custody connects to his broader goal: “We’ve been doing the same thing over and over, and we’ve seen generational incarceration, generational poverty, generational addictions,” the sheriff said. “What reduces crime? It’s not more money, more police, more harsh sentencing. It’s value. When you give people another path, they change the way they make decisions.” In 2020, Swanson’s jail also launched IGNITE, an education and job-training program that has spread to jails in at least a dozen other states, and counting.

Swanson says he wants to normalize election participation in the jail, and that this work stems from his belief that people there deserve access to the democratic process just like any other voters. “The right to vote—that is so powerful as your individual right of freedom, and I’m going to push that on every level,” Swanson told me.

Still, there is much about Flint’s jail that undercuts Swanson’s rhetoric.

Lots of people are detained here awaiting trial for very long periods—sometimes years. And in many ways, jail policies keep them isolated from the world beyond the facility’s walls; they cannot go outside, for instance. Swanson only began allowing limited in-person visits from some family members this past summer, following a damning lawsuit from civil rights groups that alleged county officials had conspired with a private telecom company to profit off ending in-person visitation and pivoting to costly video calls.

In May, The New Yorker reported on Swanson’s policy of blocking visits from families. “They’re trying to break us,” one incarcerated source told the magazine. Another said they watched people locked up in Flint “break down into despair.”

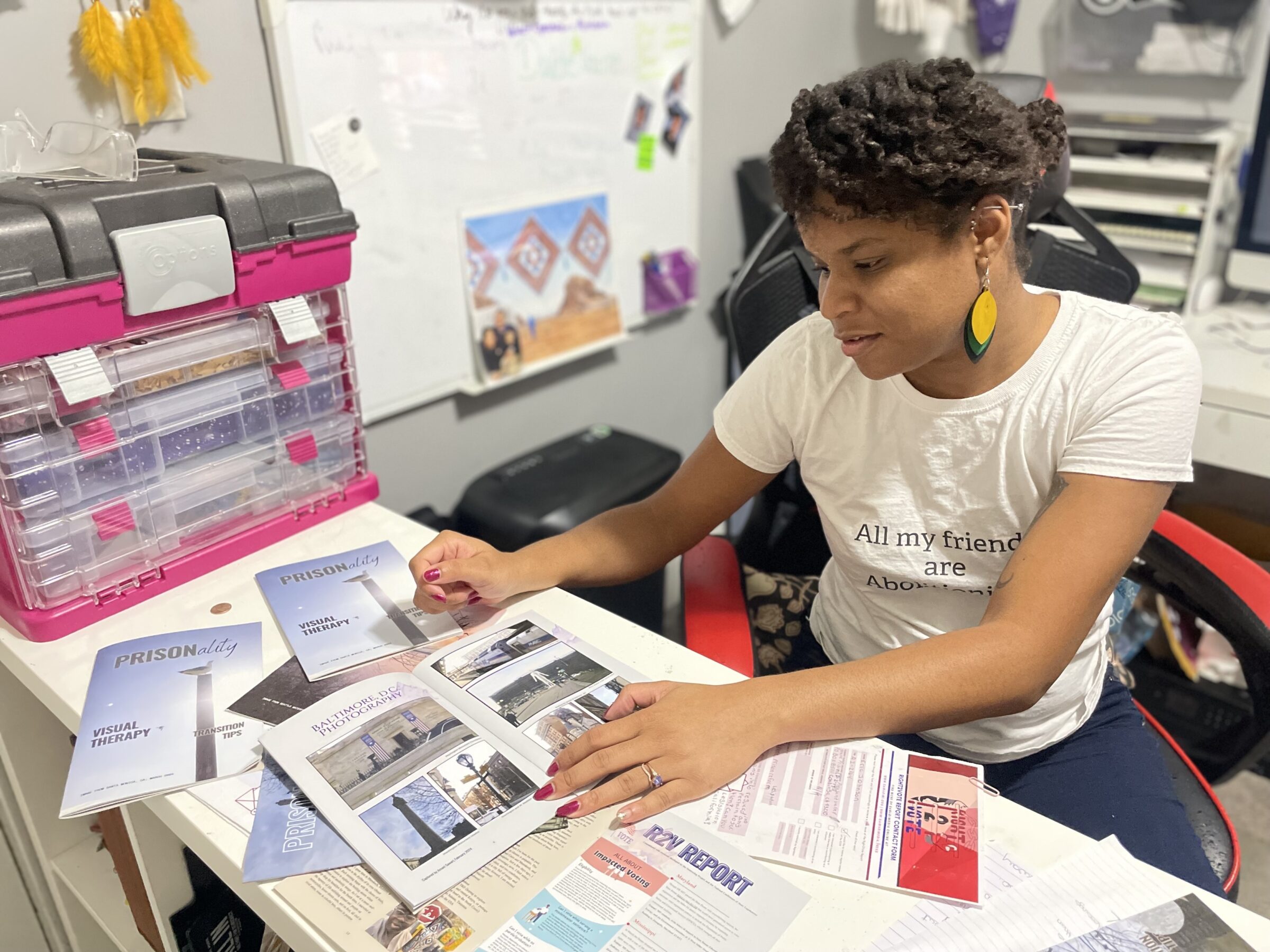

Amani Sawari, an advocate for jail voting who lives outside of Detroit, who is also the editor of a quarterly political zine called Prisonality that she mails to thousands of incarcerated people around the country, told me the programs to encourage civic participation at the Genesee County jail are the “gold standard” for any groups or communities looking to build political power behind bars.

But she said she also struggles to square the jail’s standout qualities with the casual cruelty of its conditions.

“When it comes to programming, they have something to be proud of, and there’s Percy’s leadership, the forums,” Sawari said. “But when it comes to the food, the conditions, the bunks—it’s still jail. It’s still carceral. It just sucks.”

Glover acknowledges these complaints. “The design is very inhumane, like most jails. There’s absolutely no level of comfort. I mean, look around,” he said. But, he adds, he is focused on controlling what he can.

He estimates he’s helped 2,000 people vote from jail in the last few years, and I learned quickly how important Glover’s work has felt to people detained in Genesee County. In the jail lobby, before I took a tour of the facility, I encountered a father and daughter named Carl and Katarena Maddox, who had both been incarcerated at the jail and released earlier this year. They had returned that day to celebrate their graduation from a jail-based education program. Both told me they had attended a candidate forum while detained there.

Katarena, 24, voted for the first time in her life from jail this summer during Michigan’s primary election. “It was a memorable first,” she told me. “It made me feel as if I was part of the community, because nobody has ever introduced me to voting the way the Genesee County jail did.”

Carl, 56, told me he’s been locked in this jail on and off since he was 18, and is now determined to stay free. He said that not once during his dozens of stints at the jail did staff ever mention voting—until last year, when Glover helped him register and cast a ballot for the first time in his life.

“Percy made us part of the process,” Carl said. That stuck with him: Carl said he’d attended a candidate rally in the area in September, as a free man, and that, the night before we met, he had made a point to watch J.D. Vance and Tim Walz debate on TV. “I’m seeing myself differently than I ever have. Voting, being in my community, is a big part of that,” he added.

Swanson, a Democrat, has ambitions to run for governor, and this month cruised to re-election. He was appointed to the post in 2019, made headlines in 2020 for marching with protesters after George Floyd’s murder, and then won his first election for the office later that year. That was the same year the jail launched IGNITE, which stands for Inmate Growth Naturally and Intentionally Through Education. Swanson and other jail leaders are evangelical about the program, which has been praised by a team of researchers at Harvard, Brown, and the University of Michigan who concluded in a paper this year that IGNITE and the “culture change” it’s brought about led to a sharp drop in recidivism and improved morale in the jail.

But it was difficult to reconcile that with my many observations that the jail remains, in many ways, just another embodiment of the callousness of mass incarceration.

Detainees there are fed slop. The housing units seem just as uncomfortable as those in other jails I’ve visited, and one of them is so crowded that some people have to sleep in a common area, without the relative privacy of a cell.

The judge candidates were directly confronted with the realities of pretrial detention on Oct. 3, during the question-and-answer period that followed their speeches. One man in the back of the crowd asked the candidates how they’d ensure due process. He said he’d been in the jail for three years, awaiting trial.

“I want to apologize to you,” responded Adrienne Young, a Michigan Court of Appeals judge and former public defender who would go on to narrowly win a new term on Nov. 5. “Three years waiting for an outcome and being separated from your family is an unimaginable loss for you and for your community.”

The vast majority of people in custody at this jail have not been convicted—that is, they’re detained despite still being presumed innocent—and the average length of stay as of this summer was more than 200 days, according to the jail’s staff. The situation is common across Michigan, and across the country, in large part due to a cash bail system that keeps people who cannot afford their freedom locked up. Some Michigan lawmakers want to reform this system during the upcoming lame-duck session.

After the forum, I caught up with the man who asked the question about due process. He told me that he is 42, and that he had never voted until Michigan’s primary election this year, when Glover helped him register and request a ballot. He said that the candidate forum was the first time in his life that anyone running for office had spoken to him.

Here and all over the country, sheriffs are armed with broad discretion over access to ballots and information about elections. They typically get to decide whether to allow elections officials, or organizations or individual advocates, inside jails to assist people in registering to vote or obtaining a ballot. They control the flow of mail in and out of jails. They also control the flow of information relevant to voting, like ballot guides, local newspapers, and official campaign material. They decide whether to allow candidate events like the one I attended in Flint.

And typically, in this state and elsewhere, jails have done little to facilitate democratic participation. When it comes to civic engagement, the Genesee County jail soars over a bar that could hardly be set lower: A 2021 statewide review by the Michigan nonprofit Voting Access for All Coalition found that only about a quarter of the state’s 83 counties reported having any policy in place to assist jailed people with voter registration. Anyone voting from a Michigan jail is necessarily doing so by absentee ballot, since jails there do not double as polling places, and the review found that less than half of counties reported any program to assist in that process.

“It was shocking,” Angela Davenport, executive director of the coalition that conducted this review, told me. “There’s no consistency at all.”

This matches Sawari’s experience. She told me that most officials across Michigan ignore the issue of voting rights for people in jail custody. Sawari said a small corps of advocates, herself included, has been trying to change this by going directly into jails and doing the work that the government will not. But, she said, sheriffs sometimes won’t let them in, and officials often seem totally uninterested in helping the people they detain act on their constitutional right to vote.

“We don’t expect the staff of a sheriff’s office to be voting experts,” she told me. “The problem is they feel like voting is a privilege, and that people in jail shouldn’t have access to that privilege.”

Sawari recounted a recent exchange with the top elections official in Macomb County, the third most populous county in Michigan. (The 2021 statewide survey by the Voting Access for All Coalition had found Macomb County had no programs in place to facilitate registration or voting.) “We were trying to get into that jail for years,” Sawari said. “They were unresponsive. So we contacted the county clerk, because they could help resolve a lot of registration issues if they were willing to go into the jail. The clerk, when we sat with him, was like, ‘There are people in the jail that can vote?’ He had no idea.”

Sawari added that the clerk still did not commit to making a greater effort to help people in jail vote, even after that conversation. (The Macomb County clerk’s office did not respond to multiple interview requests from Bolts.)

“Jails become dark holes of civic engagement for folks confined, because there’s no pathway to activating their rights,” Sawari continued. “They’re just stuck, stuck in the walls.”

In this context, at least, Sawari and other advocates are glad they’ve made major progress in Genesee County. Sawari said, “Them raising the bar gives us something to point to for other jails that aren’t doing anything.”

Percy Glover’s first encounter with the Genesee County jail came in 1993, when he was in his early 20s and locked up on a second-degree murder charge—the tragic result, Glover says today, of what began as a simple neighborhood rivalry among poor, aimless, bored, short-sighted young people with access to weapons.

After prison, he went back to school and then worked a slew of jobs, eventually landing at the State Appellate Defender Office as an advocate who helped people accused of crimes with re-entry and family reunification. It was not until he was on that job, six years ago, when he got a call from someone he knew at The Advancement Project, a national nonprofit promoting racial justice, that he even learned people in jail could vote.

The Advancement Project was poised to spearhead a jail-voting pilot program in Flint, Glover says, and it asked if he was interested in joining. He was, and soon after visited the jail—it was his first time in there since his incarceration—with the then-county clerk and a couple of others. They together helped more than 300 people register to vote, Glover says. He kept up that work for years on a volunteer basis, before joining the staff of the sheriff’s office. In early October, besides organizing the forum, Glover was busy hanging informational posters and distributing absentee ballot request forms, to then collect and submit them to elections officials.

He has also expanded his work beyond Genesee County, including by advocating for legislation last year that made Michigan the first state in the country to automatically register people to vote as they exit prison and regain their voting rights.

State laws concerning voting and democratic engagement for incarcerated people are generally extremely flimsy, where they exist at all. Only one state, Colorado, requires jails to establish polling places, and that law only passed this year, only requires a few hours of voting access per cycle, and only applies to certain elections. Glover hopes Michigan will consider a law similar to Colorado’s.

When I arrived in Flint a couple of days before the jail’s candidate forum, I encountered Glover outside the lockup wearing a sharp navy suit with a sheriff’s badge pin on the lapel, and a pair of immaculately clean black and white Jordans.

He’s 56 and has lived here his whole life, save for the years he spent in state prison. He came up in the 70s and 80s, when, in key ways, Flint bore little resemblance to its current form. The city’s population, which verged on 200,000 when he was born, has today shrunk to under 80,000. Job loss and white flight have produced stark segregation: Flint is majority-Black and 65 percent non-white, while the rest of Genesee County is 85 percent white. Flint accounts for about a fifth of the county’s overall population, but more than half of the local jail population.

Glover remembers a childhood in a busy city with lots of auto workers, blocks of homes with real curb appeal, kids playing. He remembers that his grandparents lived at the confluence of three sections of housing that each had their own elementary school.

We took a drive around Flint, shortly before the judicial candidate forum at the jail, Glover narrating—“Empty, empty, empty”—as we passed vacant buildings along a wide street with almost no traffic. The three elementary schools by his grandparents’ place have all closed.

He told me he believed from a young age that he would do something great one day, and that he feels now, 50 years later, that he is fulfilling that dream through his work at the jail.

Glover says his interest in civic engagement at the jail is fueled by all he did not have—all that many young people in Flint today also do not have—that might have kept him out of jail in the first place: “Somebody taking any time to care, to ask me what I was feeling, what I’m thinking. Somebody showing me a career opportunity: Have you ever thought about going to school? Exploration.”

IGNITE, the program inside the Flint jail, is optional for those held there, but very popular, in part because it comes with incentives: Participants can earn extra time on digital tablets, which they can use to watch media and communicate with loved ones. They get access to special activities, such as time in the jail’s music recording studio. They get to wear different clothes; rather than the standard-issue orange one-piece jumpsuit one gets when booked into this jail, those involved with IGNITE get to wear two-piece burgundy outfits. “If you do what we want you to do, you’ll get a reward for it,” Major Jason Gould, one of the sheriff’s top officials, told me. He said he did not realize, until IGNITE, how much it matters to wear two garments instead of one: “It makes a big difference when they go to the bathroom,” he said.

IGNITE participants meet five days a week, for an hour before lunch and for an hour before dinner, for classwork ranging from math to art history. They are given job training in a variety of fields, and can, through a local community college program, apply for employment that they can begin after release from jail.

Peter Hull, a Brown University economist who co-authored the recent report on IGNITE, told me he approached the program skeptically. “My broad sense was that these programs rarely work very well, and that in fact there’s a long history of programs like this being tried and eventually scrapped,” Hull said. But his research team found that even one month in the IGNITE program was enough to make a participant 25 percent less likely to commit “misconduct,” defined by the jail as any of a number of acts of violence or disobedience, while in the jail, and 18 percent less likely to be sent back to jail within a year of being released.

“This wild thing happened,” Hull said, “where analysis after analysis was just showing the same thing. I beat up the numbers as hard as I could, and it really does seem like something is happening here.”

The day before the October candidate forum, Glover and Major Gould took me around the jail for a tour. We wandered the five-story building for about 90 minutes.

The November election was still about a month out, and on this day Glover was hanging a bunch of posters, given to him by Sawari and other outside advocates, with information about voting eligibility and ballot access. Glover taped them on walls throughout the building and at doorways in cell blocks. “YOU CAN VOTE!” read one poster.

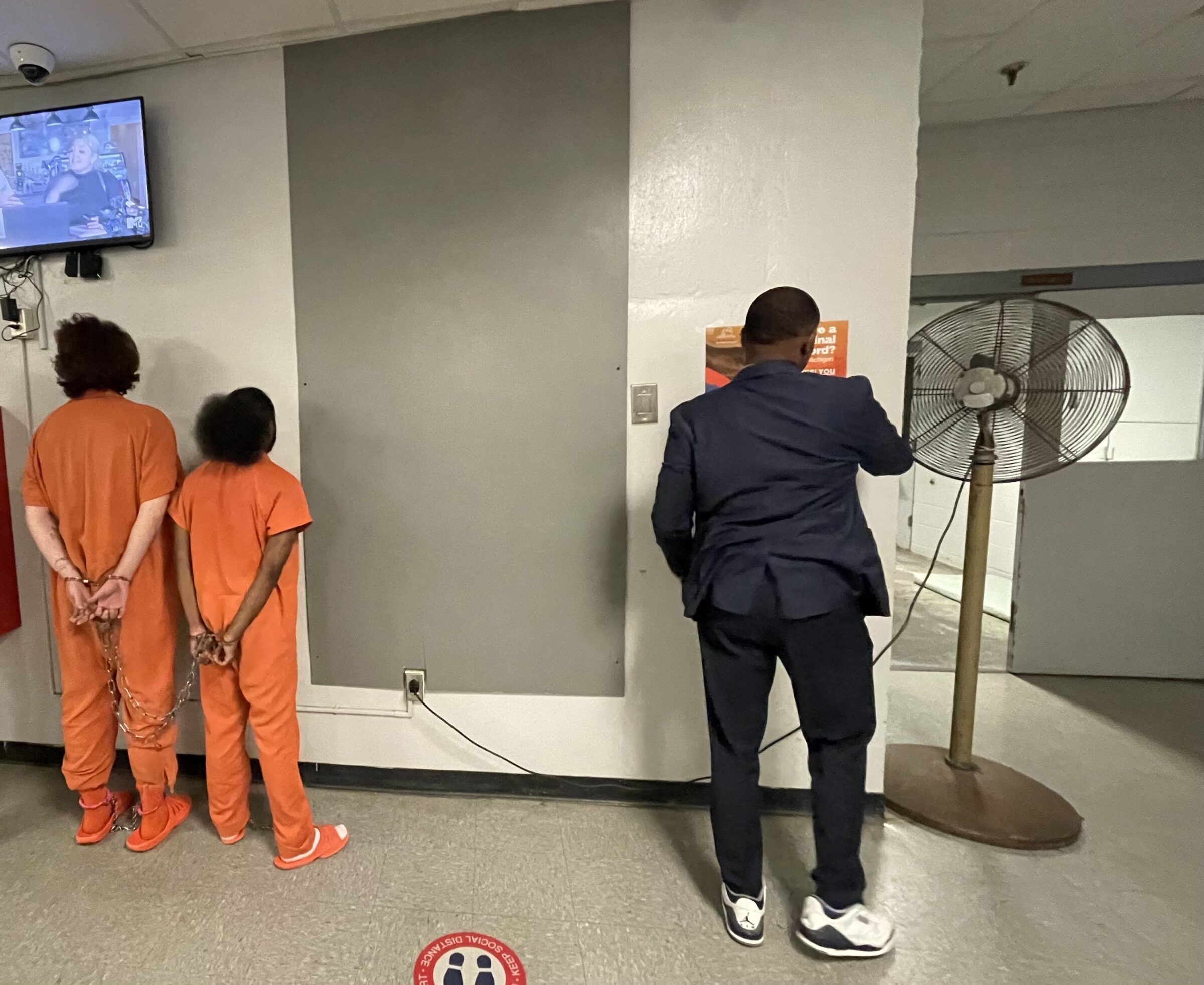

I watched him hang the first poster in the jail’s booking area. It was brightly colored and read, “Have a criminal record? In Michigan, yes, you can vote.” Alongside the posters hung advertisements placed in the jail by criminal defense attorneys. A few feet away from Glover, a group of men in orange jumpsuits, freshly returned from court, stood facing a wall, all shackled together. I saw two incarcerated men wearing white outfits, and Gould told me that these are “trustees” of the jail—a distinction that a few dozen people are given for good behavior and trustworthiness. These men were eating lunch, unrestrained.

“We depend on these guys, the trustees, because they’re doing all the work that, basically, the deputies don’t want to do: trash, serving food, sweeping floors,” Gould told me. “We couldn’t operate without them.”

I asked if the trustees get paid for their work, and Gould said, “No. The pay is they don’t have to be in a cell all the time.”

Later, inside the housing units of the jail, people in orange jumpsuits (those not participating in IGNITE programs) and burgundy outfits (the IGNITE folks) surrounded Glover as he hung posters and chatted with them. Lunch hour was winding down, and I passed by a stack of discarded trays with food scraps. The meal looked disgusting: tired green beans and white bread and two dishes—one brownish and one milky-white—that I could not identify. Gould told me the food here used to be a lot worse.

Glover had already started collecting absentee ballots, work that would ramp up in the days to come. He’d also distributed nonpartisan voter guides from the League of Women Voters, containing basic information about what was on the ballot.

A young man approached him to say he was excited about voting but that he didn’t know anything about Donald Trump or Kamala Harris. “Who should I vote for?” the man asked, and Glover told him he couldn’t answer that question. Glover told me that kind of encounter is not unusual, hence the importance of the candidate forums.

Inside the jail, I met Emmanuel Burks, a 28-year-old IGNITE participant. He voted in Michigan’s primary this year but otherwise had voted just once before in his life, during a past presidential election. “We don’t really have a voice in here. They feel like we’re just criminals. There’s an image about us,” he told me, but then added, of Glover, “he’s giving us a chance to open our voice, our mind, be heard.”

Gould said he’d show me the outdoor space, where people jailed here can get fresh air a few times a week. When we got there, though, I was struck by the fact that it is not really outdoors, but is rather a plain room with brick walls, half of a basketball court, one hoop, and two open-air, vertical, barred windows that let through some breeze.

I mentioned to Gould that Glover’s work on civic engagement and IGNITE and the general culture change those programs are meant to signal did not erase the many ways in which the people locked inside here are kept isolated. How can the office pitch itself as so humane when the folks in its custody are unable to touch actual earth, or feel a raindrop—or, until recently, ever hug their own family members—sometimes for years on end?

Gould didn’t dispute the premise, but told me, “They’re not supposed to be here more than a year. That’s how it was designed.”

In the jail’s one women’s unit, I met Windy Weatherford, who has been locked inside for two and a half years, awaiting trial.

She was deemed such an excellent IGNITE participant that she was elevated to one of two special cells in the women’s unit that feature nicer linens and thicker mattresses than what the rest of the population gets. I learned that these relative luxuries were purchased through a donation made by NBA player and Flint native Kyle Kuzma. His name is posted in big block letters in the corner of the cell block.

“We do have some nice orthopedic mattresses, and it helps,” Weatherford told me. “You feel like you’re sleeping on concrete on the other mattresses.”

The next day, at the forum, Glover stood off to the side as the candidates for office each gave pitches. Some of them noted how unusual the event was.

“This does not happen for the people I formerly represented,” Adrienne Young, the public defender-turned-appellate judge, said. “I’m here because you matter, and you should vote because you matter.”

Afterward, I spoke with Kyra Harris Bolden, who was running in a hotly contested race to retain her seat on the Michigan Supreme Court. (Bolden would go on to win, helping solidify a liberal majority on the court.) She told me that candidates like her are typically steered by consultants toward a very different type of campaigning from what she was doing that day. “You get a list of registered voters and you target that population of people that you know are going to vote. Your absentee voters, your vote-in-every-single-election people,” she said.

Bolden recently experienced how public institutions shun people involved in the criminal legal system. After joining the court at the start of 2023, she hired a formerly incarcerated man as a law clerk. but this gave way to a public outcry, led by one of Bolden’s fellow Democratic justices, who felt the clerk’s criminal record disqualified him from the job. The clerk resigned within days.

Bolden told me it was her second time participating in a forum at this jail, and that she’d been invited to zero others across all the rest of the jails in Michigan.

I spoke also with Latoya Willis, who was running in a contested race for a seat on the Court of Appeals. (She was nominated by Democrats and lost to Republican nominee Matthew Ackerman.) “I’ve never been to an event like this,” Willis told me. “It’s a huge voting population who still has a voice, and an important voice, because they see up close and personal what these judges do.”

Without this forum, she wondered: “How many people would even know that they still have the right to vote while they’re here?”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.