Out of Sight

Officials have responded to an overcrowding crisis in Texas’ largest jail by shipping more people from Houston to far-flung, for-profit lockups with even worse oversight.

Michael Barajas | December 22, 2023

Bolts this week is covering the crisis in local jails, and the county boards that oversee them. Read reporting from Los Angeles, Harrisburg, and Houston.

Evan Lee had trouble getting the medication he needed for mental illness and other health issues after being booked into the Harris County jail, just three days from Christmas in 2021. As a result, Lee’s family says he deteriorated during his time inside the hulking lockup in downtown Houston, until March 9, 2022, when he was badly beaten and injured by another inmate.

According to a lawsuit Lee’s family filed against the county earlier this summer, it took two days for jail officials to give him any medical care despite visible injuries like facial bruising. Even then, according to the lawsuit, jail medical staff “simply looked at Mr. Lee and sent him back to his cell without any treatment, observation or further diagnostic testing.” On March 18, more than a week after the fight, jail staff finally sent Lee to a hospital because of how disoriented he was. Doctors found serious head injuries, including two areas of bleeding in his brain, and pronounced him brain-dead two days later.

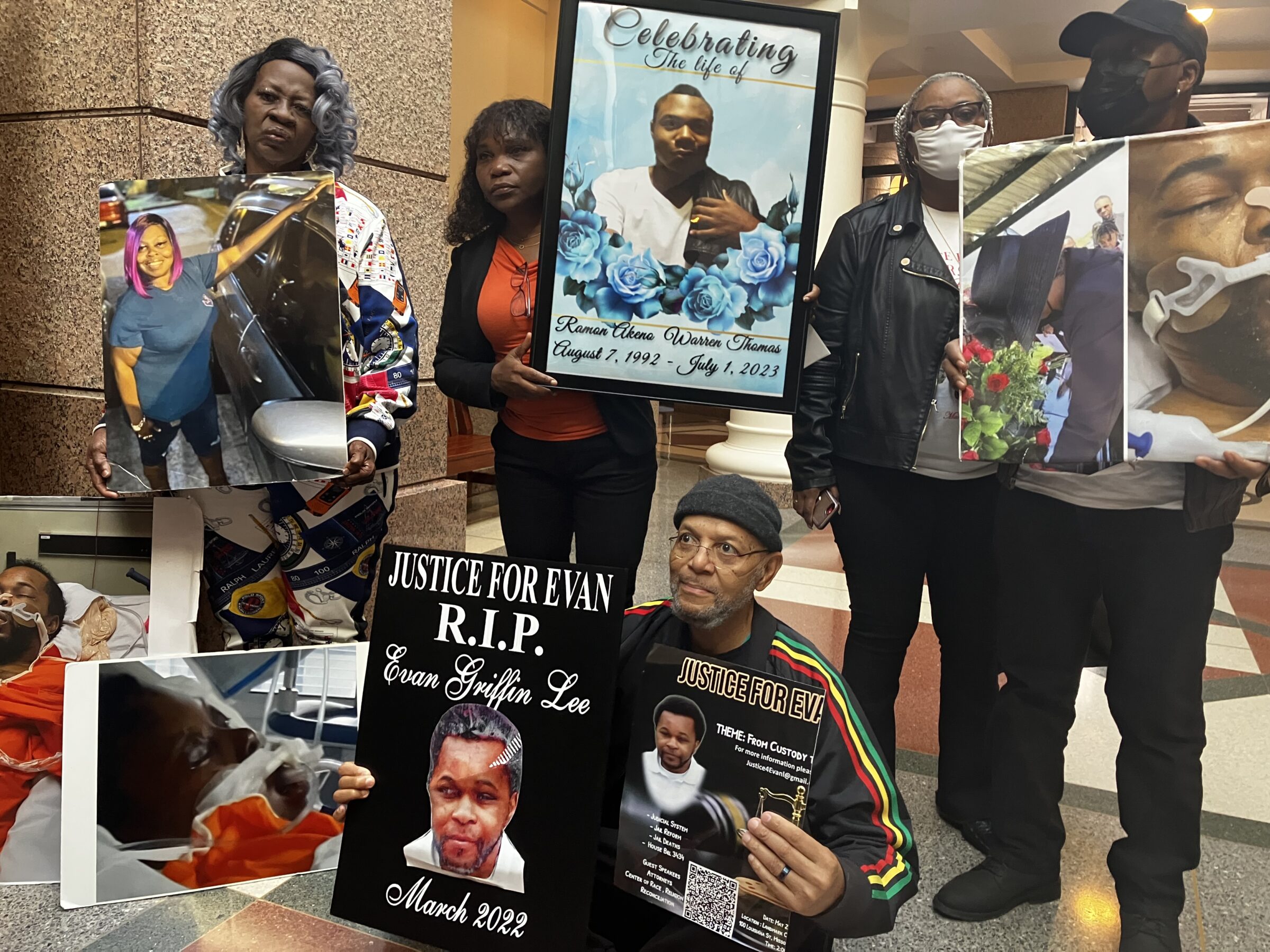

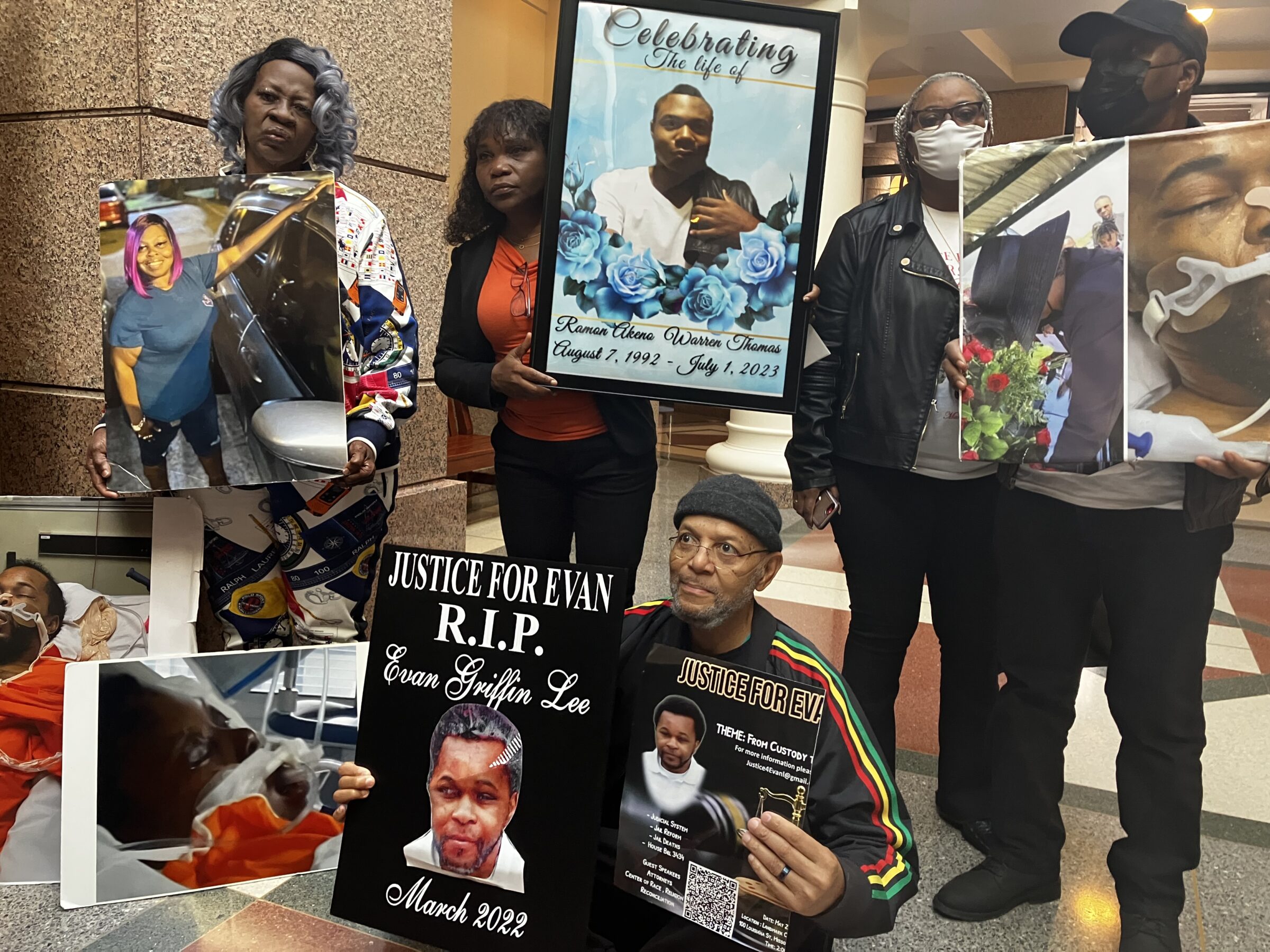

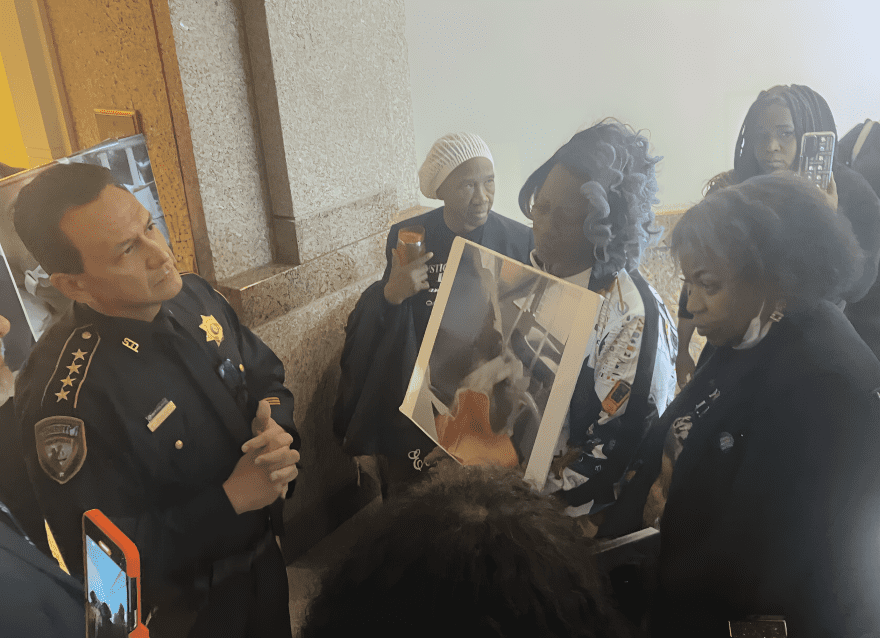

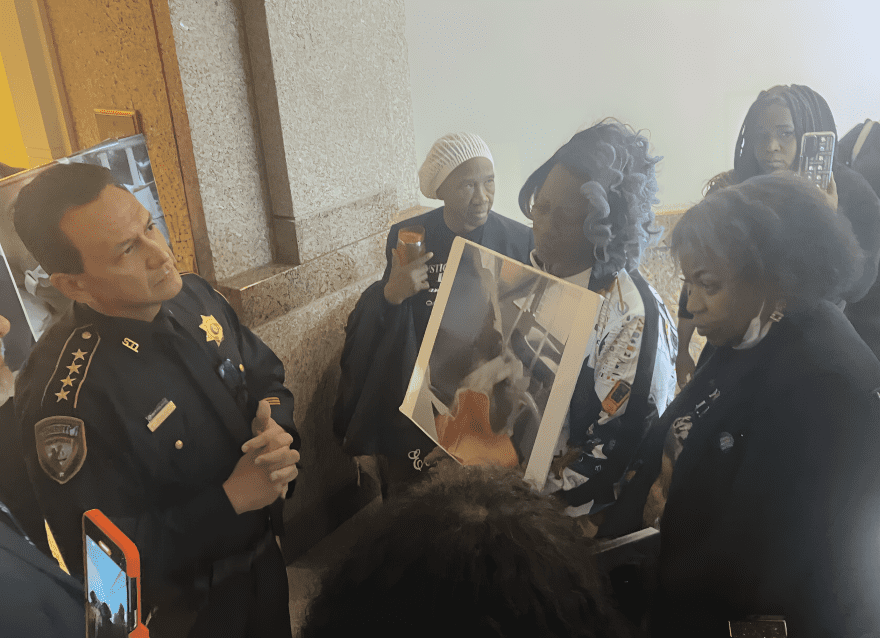

Lee, 31, was one of at least 28 people who died after being in Harris County jail custody in 2022, when Texas’ largest jail system saw a record wave of deaths. Alongside other mourning parents, his mother Jacilet Griffin-Lee now religiously attends meetings held by the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, a state regulatory agency. For more than a year at these hearings, Harris County has been called to the carpet for violating minimum safety standards, including for lapses in medical care and monitoring of people in custody. Griffin-Lee and other family members drove the 160-mile trip from Houston to Austin for the jail commission’s last hearing on Nov. 2 and stood at the back of the room, holding poster-sized photos of loved ones lost to the jail as an entourage of Harris County officials testified about efforts to improve conditions.

After Harris County Sheriff Ed Gonzalez left the hearing room, Griffin-Lee peppered him with questions in the basement level of the Texas capitol building. “It’s a horrible facility, it just hurts for people to get the death penalty while they’re waiting for their case,” she said as other grieving mothers circled the sheriff. “We should not be getting the kind of letters we’re getting from inmates that are there and what they’re witnessing.”

Harris County officials have largely blamed the jail crisis on overcrowding and short staffing; as of the November hearing, more than 9,000 people were detained inside a Harris County jail system that had more than 200 vacant jailer positions. And yet they haven’t announced major new efforts to shrink the population they wish to jail. Instead, in response to the jail commission’s escalating pressure, they’ve started shipping even more people in their custody to for-profit lockups far from Harris County.

Last month, after the state jail commission threatened to reduce Harris County’s jail capacity if it didn’t comply with minimum standards, the county’s governing body—its five-person commissioners court—unanimously approved a $11.3 million contract to send up to 360 people to a private prison in Mississippi. That’s on top of the roughly 1,300 people whose detention the sheriff’s office already outsources to other private lockups outside the county.

Any pretrial detention, which accounts for more than 70 percent of the county’s jail population, separates families; it also makes mounting a defense more difficult, putting pressure on people to plead guilty. But those challenges multiply when people are sent hundreds of miles away. It may even compound the backlog in criminal cases that has contributed to the overcrowding crisis. According to county data, people now spend on average nearly 200 days in Harris County jail custody, most waiting for their case to be processed, which is far greater than the national average jail stay of 33 days. Defense attorneys say more outsourcing could add to delays in cases as more people must be transported back to the county for court hearings.

“It’s hugely expensive, it draws things out, and it destroys relationships between clients and lawyers and clients and their families,” Alex Bunin, Harris County’s chief public defender, told me. “It creates just all kinds of anxieties that can play out later and affect things like recidivism and getting a job and getting back into society.”

The outsourcing, ostensibly a response to dangerous jail conditions in Harris County, will put even more people in the hands of private prison companies with their own histories of abuse.

CoreCivic, the private prison giant that inked the new contract with Harris County last month to detain people in one of its Mississippi lockups, has long been accused of short staffing, excessive force, and poor treatment at its facilities. Another company Harris County contracts with to house up to 500 people in one of its Louisiana prisons, LaSalle Corrections, has a similarly troubled track record; in 2020, the company lost its contract to run a bi-state jail on the Texas-Arkansas border following years of lawsuits over deaths on its watch.

Harris County detainees shipped to the LaSalle Corrections Center in northwest Louisiana, nearly 300 miles from home, have already warned of dangerous conditions. Rahan Atia, a Houston defense attorney, told me that he started hearing complaints of extortion and threats of violence after he took over the cases of several defendants held there.

In September, Atia asked a Harris County judge on one of his cases to prevent the sheriff’s office from sending a client back to LaSalle after he’d been brought to Harris County for a hearing. (Atia asked that his client not be named to protect his privacy.) The request prompted a hearing over whether to keep the defendant in Harris County.

Lawyers for the county opposed the motion. “The same people that are out there are here,” said Graylon Wells, a lawyer with the Harris County Attorney’s Office, according to a transcript I obtained of the hearing.

Wells said that the jails managed by the county also present dangers, questioning whether the defendant would be any safer staying in Harris County. “My confusion here is inmates rotate from LaSalle to here, so why is he safer here than he is in LaSalle?” Wells asked. Victoria Jimenez, a lawyer with the sheriff’s office, told the judge, “It is nearly impossible to prevent any type of extortion from happening … What if something happens to him here?”

“Is something going to happen to him here?” the judge, Natalia Cornelio, asked. “God forbid, no. Hopefully not,” Jimenez replied, then added, “Things happen every day in that jail.”

Atia told me the hearing felt like a troubling admission by the county that it couldn’t ensure safety for anyone in its custody, whether in the facilities they run directly or elsewhere. He credited Cornelio for taking the matter seriously and granting his request to keep the defendant in Harris County after the extortion attempts, but he added that other judges refused to even hear similar complaints. “Other judges went, ‘Well you know, it’s just the culture,’” he said. “No, it’s not just the culture. We need to stop this.”

Neither the sheriff’s office or LaSalle representatives responded to my requests for comment or questions sent by email for this story.

The outsourcing also decreases oversight of the conditions under which people are detained. Jails inside the state fall under the regulation of the Texas jail commission and are required to hold independent law enforcement investigations into each death in custody and report them to the state attorney general. (As I wrote earlier this year, some Texas sheriffs have tried to undermine these requirements.)

But those requirements stop at the state line.

Andrea Armstrong, a law professor at Loyola University in New Orleans who works with her students to compile information about deaths in custody across Louisiana, says that her state has comparably weak jail regulations and oversight. She pointed to the case of Billie Davis, a 35-year-old man who died after Harris County sent him to the LaSalle Correctional Center last year. Had he died in Texas, Davis’ death would have triggered a report to the Texas AG as well as an independent police investigation. After Davis died in Louisiana, Texas jail reform activists struggled for months to find out what happened to him. This year, activists finally tracked down a coroner’s report, which concluded that Davis died from the result of “multiple blunt force traumatic injuries during a fight in custody” and ruled his death a homicide.

Armstrong said Louisiana law doesn’t require any particular investigation into deaths in custody other than by a coroner, so it’s unclear what, if any, other inquiry occurred into Davis’ death. (Sheriff’s officials in LaSalle Parish, where the facility is located, didn’t respond to my questions for this story.) “In our work documenting deaths in Louisiana prisons and jails, one of the most difficult facilities to obtain information from is privately operated facilities,” Armstrong told me. “My students often end up in extended conversations with legal counsel. It’s a difficult undertaking.”

Brandon Wood, executive director of the Texas jail commission, acknowledged the outsourcing of detainees may decrease oversight of the conditions in which they’re detained. “I don’t know if I want to use the term, ‘black hole,’” he told me, “but it is one of those things where once they are no longer within the state of Texas, we lose a lot of our authority regarding those inmates.”

Advocates for jail reform in Harris County have urged local officials to prioritize reducing the jail population over more outsourcing. Krishnaveni Gundu, executive director of the Texas Jail Project, which monitors jail conditions and advocates for incarcerated people and their families, says there have long been other options.

For instance, she pointed to a 2020 consulting report commissioned by the county that recommended prosecutors dismiss all non-violent felony cases older than nine months in order to cut the county’s case backlog—especially since more than half of those cases eventually wound up dropped or deferred anyway.

Harris County District Attorney Kim Ogg has balked at such recommendations, calling them unrealistic. Ogg, who faces a heated primary challenge to keep her seat next year, was also admonished by her own party earlier this month, with Harris County Democratic Party precinct chairs voting overwhelmingly to pass a resolution that condemns her for, among other things, “[standing] in the way of fixing the broken criminal justice system.” Ogg has also clashed with local judges who have supported bail reform and pursued efforts to relieve the local jail.

Gonzalez, the local sheriff, has said that outsourcing is “not a preferred solution” and has made halting efforts to release people—including flagging people in his jail system who present no public safety risk for consideration by the DA’s office and judges. “We incarcerate way too many people,” the sheriff told the grieving families who had gathered in November to confront him. “Right now, law enforcement is on the front lines of three things in this country: mental health, addiction and poverty,” he said. “We should not be on the front lines, we should find other alternatives to that, instead of people ending up incarcerated.”

Even with such rhetoric from officials, Harris County continues to double down on jail-based solutions to the crisis. In addition to the increased outsourcing, the county earlier this year approved an additional $645,000 to expand services for people in the jail who have been found incompetent to stand trial—a program that county administrators have proposed expanding even further. Gonzalez himself has suggested that the county should seriously consider new jail construction.

All five members of Harris County’s governing body, even those who have clashed with the DA, approved the new outsourcing contract last month. County Judge Lina Hidalgo, who leads the county government and supported the contract, told Houston Landing that it “breaks my heart” and that she wants to be “figuring out a solution.” But, she added, “I don’t have it yet. It’s a little scary to say I’m working on one and I don’t know if we’re going to find one.” (Hidalgo’s office didn’t respond to my questions for this story.)

But Gundu insists there are many alternative policies for the county to pursue. “Instead of lining the pockets of private prison companies, we could be investing those taxpayer dollars in robust evidence-based solutions that actually promote public safety,” she told me. “Such as access to affordable and stable housing, crisis respite centers, psychiatric ERs, community based mental health care, guaranteed income programs, equitable access to healthcare—any of these solutions is guaranteed to keep our communities safer than a jail.”

Meanwhile, families of people who died in Harris County jail custody say they will continue to pressure officials for accountability, including by attending the next state jail commission hearing. “I want to let the commissioners know that we’re watching and we care about our loved ones, even when they are in their worst state,” Lee-Griffin said after the last commission hearing. As it approaches two years since her son’s death, Lee-Griffin told me she tries to focus on good memories of him, like his love for sports and for his community.

For others at last month’s jail commission hearing, the pain of losing a child to jail still felt fresh. Dianne Bailey Rijsenburg showed me photos of her 30-year-old son, Ramon Thomas, who died after being incarcerated at the jail this summer. Tears welled in her eyes as recalled praying to herself and pacing around her house after she got the call that he had died this summer, as if trying to stabilize herself with movement and faith.

“How can those people come and rip your children from you like that, like they’re nobody?” she asked, holding a photo of her son bordered by blue flowers.

Stay up-to-date

Now is the best time to support Bolts

NewsMatch is matching all donations (up to $1,000) through the end of the year. Support our nonprofit newsroom today.