Local Cooperation with ICE Is on These Counties’ Ballot in Nov. 2018

The scope of local immigration enforcement is on the ballot in November.

| October 10, 2018

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

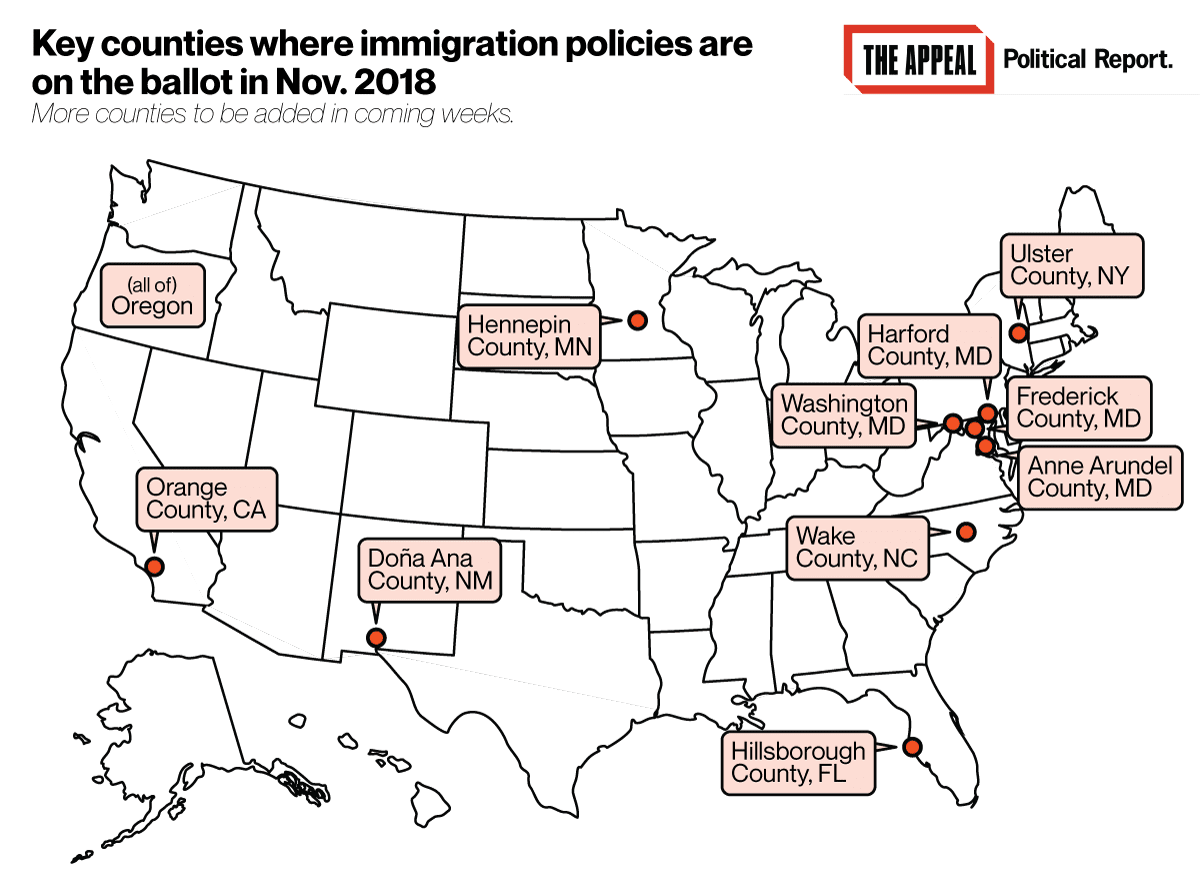

Local officials wield great power over a county’s immigration policies. Many of their decisions escape widespread attention, but the organizing against ICE partnerships broke through in primaries this year, helping topple incumbent sheriffs in Milwaukee and in Charlotte. The scope of local immigration enforcement is now on the ballot in November. Below I profile 9 counties where the stakes are especially high and the contrast especially stark.

In five of these counties, the debate revolves around whether to participate in 287(g), an ICE program that allows local deputies to act as federal immigration agents. Elsewhere, local authorities partner with ICE through paths that are less visible and open but that have nevertheless drawn considerable protest.

Read our coverage of the results of these elections in The Appeal. Below, you will find our pre-election preview of each of these races.

California: Will Orange County continue circumventing the ‘sanctuary state’ law?

In 2017, California adopted Senate Bill 54, a “sanctuary state” bill that limits contact between local law enforcement and federal authorities. The Orange County sheriff’s office has organized against the law ever since. It pushed the county to join the Trump administration’s lawsuit, and it now posts the dates at which people are scheduled to be released from jail online; the idea is to circumvent the new limits on communicating with ICE by making information altogether public. In addition, Sheriff Sandra Hutchens has sought to expand the number of immigrants that the county holds for ICE. Immigrants are detained in terrible conditions in Orange County, according to a 2017 Department of Homeland Security report on the Theo Lacy Facility, which features 24-hour solitary confinement, and unsanitary food and showers.

Hutchens is not seeking re-election this year and immigrant rights’ advocates see the open race as an opening for change. Jonathan Paik, the director of KRC in Action, sees it as an opportunity to elect a sheriff who is not “actively trying to find workarounds to target immigrant communities” and “does not partner with the Trump administration.”

The candidates are Undersheriff Don Barnes and Duke Nguyen. (The ballot does not include party IDs, but Barnes is a Republican and Nguyen a Democrat.) Barnes, who has worked closely with Hutchens, is running as a dam against California’s reform efforts. Asked what changes he would push for as sheriff, he responded that he would “speak out against misguided criminal justice reforms and advocate in Sacramento for their repeal.” He has championed opposition to SB 54 and he says he would continue posting release dates because he views limits on immigration enforcement as threats to public safety. He said during a debate that assisting ICE is a matter of targeting “high-level criminals.” But Orange County has alerted ICE of a broad range of people; a spokeswoman for the sheriff’s office told the Washington Post in March that they would even make public the release dates of people whose charges have been dropped. “They use racially coded language to go after the immigrant community,” Roberto Herrera, the community engagement coordinator at Resilience Orange County, told me of the sheriff’s office. “They paintbrush the immigrant community as criminals as a whole.”

Nguyen, who came to the United States as a refugee in 1981, says that he would end the policy of posting release dates online. He argues that cooperating with ICE can be valuable in targeting “violent folk,” but that it would take a court order for him to honor an ICE “detainer” request. “I have no way to check on the status of a person, and I’m not going to hold that person at will for some sort of federal request,” he said at a public forum. Nguyen has focused his campaign on changing approaches to homelessness by resisting its criminalization and by urging Orange County to spend $700 million on a program to alleviate homelessness.

The sheriff’s office was rocked by numerous scandals, most recently reports of widespread misconduct in how deputies use jail informants, and the discovery that the county’s jail telephone contractor was recording conversations between detainees and their attorneys and allegations that the sheriff knew about this. Barnes supports keeping the same telephone contractor.

Orange County’s politics have been shifting, and local advocates speak of an intense mobilization around issues relating to immigration. “No matter the result of the future elections, there is an awoken giant that is really that is willing to exercise that power,” Herrera said.

Maryland: 3 counties are in ICE’s 287(g) program. How many after November?

ICE’s 287(g) program deputizes local officers to act as federal immigration agents, research the status of people held at the county jail, and detain people they suspect to be undocumented. Three Maryland counties are part of 287(g): Anne Arundel County (which is home to Annapolis, the state capital), Frederick County, and Harford County.

This partnership has strained the relationship between local government and residents. “It creates a climate of fear, particularly for the Latino community and communities of color,” Jose Perez, the deputy general counsel of LatinoJustice PRLDEF, told me. Immigrants are reluctant to contact law enforcement and broader public services, adds Elizabeth Alex, the senior director of community organizing at CASA of Maryland. “Parents particularly are opting to stay quiet and staying home, and not accessing services” that their children are eligible for, she told me.

Complicating matters, the power to join or terminate 287(g) agreements rests in different offices: in Anne Arundel, ICE’s agreement is with the county executive, while in both Frederick and Harford the responsibility lies with the sheriff.

Each of these three offices is on the November ballot. Each features a GOP incumbent who defends 287(g) against a Democratic challenger, typically by warning that quitting the program would mean releasing “criminals” “back onto the street,” as one sheriff put it—an argument that conflates crime and immigration and undermines due process; it also blurs the line between different grounds of detention since one is not being held on criminal charges if only held based on suspected immigration status. The script is inverted in a fourth county, Washington, where a GOP challenger to the Democratic sheriff is running on a pledge to join the 287(g) program.

Anne Arundel County

Anne Arundel County voted for a Democratic presidential candidate in 2016 for the first time in more than 40 years. But Steve Schuh, Anne Arundel’s Republican county executive, had his county join the 287(g) program soon after. Schuh has also overseen another deal with ICE: an agreement to detain immigrants on ICE’s behalf in exchange for payments.

In June, in the run-up to a protest family separation policies, Schuh’s Democratic challenger Steuart Pittman committed to withdrawing from both ICE deals. Pittman said he would use the freed-up jail space for a drug treatment facility. “Our biggest problem right now is beds for people who want drug treatment,” he told the Capital Gazette.

Schuh charges that Pittman’s positions would weaken public safety. “I am alarmed by my opponent’s plan to release illegal immigrants charged with serious crimes into the community,” reads a Schuh campaign mailer. But the people targeted under 287(g) are often arrested for low-level offenses like drug possession and disorderly conduct, Nick Steiner, an attorney with the ACLU of Maryland, told me. “I think [Schuh] is trying to ride this national bandwagon that the way to unite the right is to use immigrants as scapegoats,” Axel said.

The sheriff’s election features the same divide. Republican Jim Fredericks wrote a Baltimore Sun op-ed calling 287(g) “an extremely important public safety tool,” while Democrat James Williams supports dropping out of both ICE deals. “The bed space could be used for better purposes, such as, for the treatment of those with a mental health crisis,” he told me.

Frederick County

First elected in 2006, Sheriff Chuck Jenkins wasted little time before signing a 287(g) agreement in 2007—and he has been a staunch defender of the program ever since. He has testified about it in Congress or in Attorney General Jeff Sessions’s presence, and he called 287(g) a “real key piece of national security” at a public event last year.

Jenkins claims that the sheriff’s department has faced no racial profiling allegations since joining 287(g). But in 2009, a woman alleged she was profiled and arrested by local deputies while eating lunch. Federal courts later ruled in her favor, finding that she was unlawfully detained based on immigration status; a federal judge ruled in September that Frederick County is liable for damages. Perez told me that another woman has alleged being targeted by profiling in Frederick County earlier this year. “It appears that this is still ongoing,” Perez said, faulting the sheriff for creating a climate conducive to such violations. Jenkins came into office on a “lock them up, ship them back” message and kept up that rhetoric. “What do you expect deputies to do but to follow his lead?,” Perez asks.

In November, Jenkins faces Democrat Karl Bickel in a rematch of the 2014 election. Himself a former employee of the sheriff’s office, Bickel has not said whether he would end the 287(g) program. However, he proposes to conduct an audit. “Questions about the value of the 287g program need to be answered with accurate data,” according to his website. “We have more urgent priorities than immigration,” it says elsewhere on the site, referring to the opioid crisis.

Harford and Washington counties

Harford County (a traditionally GOP-voting county north of Baltimore) joined 287(g) in 2016 under the guidance of GOP Sheriff Jeffrey Gahler. In November, Gahler faces Christopher Boardman, a Democrat who says he would withdraw from the program. Boardman wrote a Dagger column in 2016 against Gahler’s decision to join 287(g), warning that this would entangle the county in legal battles and financial harm.

The roles are flipped in Washington County, which is not in 287(g). Here it is the challenger (Republican Brian Albert) who proposes joining it and frames undocumented immigrants as a threat to public safety. “We don’t have as bad a problem as some of the more urban areas, but we want to get ahead of it and tackling it before it does become a problem,” he told LocalDVM.com. The incumbent sheriff (Doug Mullendore, a Democrat) opposes joining 287(g), questioning whether it would be financially viable. This is a conservative county that voted for Trump by 30 percentage points, but Mullendore has been sheriff since 2006.

Minnesota: ICE looms over Hennepin sheriff’s race

Sheriff Rich Stanek of Hennepin County (home of Minneapolis) has drawn protests over his cooperation with ICE. His relationship with the federal agency now looms large over his reelection bid, whose first round is in August.

Stanek’s office asks the people it books their birthplace; if they were born outside the United States, he sends their information and fingerprints to an agency that shares them with ICE. Stanek also arranges calls between ICE and foreign-born detainees, reportedly without telling them of their right to refuse. Local officials have criticized these practices, and the county commission recently approved a plan to better inform immigrants of their rights and provide them legal representation. Stanek’s detention policies have also drawn attention: He informs ICE before releasing certain immigrants. Although he doesn’t honor ICE detainer requests out of concern that they are illegal under current law, he has worked with the Trump administration on new plans to facilitate the transfer of undocumented immigrants into ICE’s hands. “We want to find a way to say yes,” he said in 2017 of ICE detainer requests.

Stanek is a Republican sheriff in a Democratic-voting county, a dynamic facilitated by the fact that Minnesota lists no party affiliation in sheriff’s races. Stanek and two Democratic challengers, David Hutchinson and Joseph Banks, ran on a single ballot on August 14. Stanek and Hutchinson grabbed the top two spots, and moved on to a November runoff.

In challenging Stanek, Hutchinson has used immigration to spark partisan fault lines. “You will notice the difference between a Republican sheriff and a Democratic sheriff, a sheriff who stands with ICE and a sheriff who stands with immigrants,” he said in May. Hutchinson has committed to not asking people their birthplace or immigration status. Banks also wishes to shift immigration policy, committing to “find better ways to serve, inform, and uplift undocumented immigrants.”

New Mexico: Doña Ana sheriff race puts spotlight on Operation Stonegarden

Doña Ana County Sheriff Enrique Vigil lost in June’s Democratic primary. He was weighed down by a series of scandals, but also by controversies regarding his role in federal immigration enforcement. “Deputies working under Vigil assisted the United States Border Patrol with hundreds of apprehensions over the course of three years” despite Vigil’s insistence that his office was playing no immigration role, Kate Bieri reported for KVIA in May.

The context for this cooperation is Operation Stonegarden, a program through which the federal government provides localities with a grant in exchange for their assistance in border activities. Vigil defended Doña Ana County’s Stonegarden grant as “instrumental in providing the additional funds needed to combat crime,” and the county commission agrees: It voted in September to accept a new $750,000 grant. But the program can involve counties in immigration enforcement. “The idea that you’re going to be watching the border inherently requires local law enforcement who receive these funds to think of themselves as doing immigration work,” Jay Diaz, of the ACLU of Vermont, has said about Operation Stonegarden’s impact.

“The reality is that this kind of money has strings attached,” Johana Bencomo, the director of community organizing at NM CAFé, told me. “It’s about what kind of public servant do you want to be. Do you want to be one that’s attached to money or one that’s serving your community and what your community needs?”

In contrast to Doña Ana County, the supervisors of Pima County, Arizona, ended their participation in Operation Stonegarden in September, terminating a grant of $1.4 million.

The candidates for Doña Ana sheriff are now Kim Stewart, who won the Democratic primary, and former Republican sheriff Todd Garrison. At a candidate forum on Sept. 15, both were asked if they have an ethical issue with the Stonegarden grant. Both answered that they do not. Garrison strongly defended it and its importance for law enforcement; Stewart called immigration assistance an “obligation” that her office would owe federal authorities due to the commission’s decision. “It doesn’t matter what my position is, that’s what it says in the grant, and that’s what we as a community have decided to accept in 2019,” she said.

Nevertheless, Stewart suggests on her website that she may minimize assistance. “If DASO [the sheriff’s office] is receiving grant money from the federal government and there is any clause which can compel DASO to assist ICE or CBP [Customs and Border Protection], we need to carefully avoid situations where DASO renders routine assistance,” she writes. “When we become the immigration police, we shut the door forever on those who need our help.” During his tenure as sheriff, Garrison staked aggressive stances on immigration and border security. He denounced federal immigration reform and criticized President Barack Obama’s decision to establish a national monument as weakening public safety. In 2012, advocates cited complaints that Garrison’s deputies were asking for people’s immigration status during traffic encounters.

New York: Ulster County sheriff loses primary fought over immigration and opioids, but Nov. is a rematch

Paul Van Blarcum faced no opponent in 2014 when he won a third term as the Democratic sheriff of Ulster County. In fact, he was endorsed by the Democratic, Republican, Independent, and Conservative parties. But Van Blarcum was resoundingly rejected by his party on Sept. 13, losing the Democratic primary 82 percent to 18 percent to Juan Figueroa, a retired state trooper. What changed? “Trump made us look at these local issues and evaluate our local elected officials and ask ourselves, ‘is this what we want?’” Andrew Zink, head of the Ulster County Young Democrats, told The Nation. Van Blarcum has been in office since 2007, but the Trump era made it more widely glaring that his policies are relevant to political contestation.

In 2015, Van Blarcum began to check for arrest warrants for anyone entering the Department of Social Services (DSS) to gain access its services. He stopped the practice when the state attorney general’s office questioned its legality and slammed its disproportionate impact on people of color. He has also drawn attention for statements he issued on the Facebook page of the sheriff’s office. In 2015, he urged licensed residents to “please” carry a firearm. Two years later, he called for boycotting the National Football League over some players’ actions protesting racial injustice. “They show an utter lack of patriotism and total disrespect for our veterans,” he wrote.

Van Blarcum proactively cooperates with ICE. His office notifies ICE of foreign-born persons it arrests. “We do immigration-naturalization checks on everybody that comes in,” he told Hudson Valley One. “We would get a hold of customs and immigration and ask if they’re interested in picking the person up,” he explained elsewhere. Figueroa casts Van Blarcum’s “hard-line policy of reporting immigrants” as a threat to public safety. “Immigrants should feel safe to seek the protection of the law,” a Figueroa flier says. Figueroa would provide ICE information when ICE has a warrant and when an individual is convicted of a felony. “I am not an extension of ICE and I will not be contacting ICE for minor offenses,” he said.

Figueroa has also denounced Van Blarcum’s policy of checking DSS visitors. “What he did there was to take on the underprivileged that we have in our community,” Figueroa told Hudson Valley One. “The poor people who aren’t going to say anything because they’re there to get help.” In addition, Figueroa has spoken about changing the county’s policies on opioids. The opioid crisis “is not a problem we can simply arrest our way out of,” he wrote in an April op-ed, and he contrasts the prevailing emphasis on prosecution with approaches focused on treatment and public health.

Van Blarcum and Figueroa face each other again in November because Van Blarcum is endorsed by the Republican, Independent, and Conservative parties. Ulster County leans Democratic—it hasn’t voted for a GOP presidential candidate in 30 years—but Van Blarcum could win if he retains enough support among Democratic voters.

North Carolina: Wake County sheriff race struggles for media visibility, with 287(g) at stake

Wake is one of the biggest counties nationwide with a 287(g) agreement. Home to Raleigh, it still leaned Republican when Donnie Harrison was first elected sheriff in 2002. Explosive population growth has upended the county’s politics since then (Hillary Clinton won by 20 percentage points in 2016), but Harrison remains committed to the aggressive enforcement policies he implemented in the 2000s. He has called 287(g) a “deterrent” against crime, he insists that the traffic checkpoints his office conducts do not affect undocumented immigrants, and he rejects efforts to create alternatives to government-issued identification.

Harrison, a Republican, is up for re-election against Democrat Gerald Baker. Despite all the powers of the sheriff’s office, this election is largely invisible in English-language media, as local observers and a search of local publications confirmed. As of Oct. 9, articles detailing Baker’s views on immigration and 287(g) can be found only in Spanish-language publications like Qué Pasa Noticias and La ConexiónUSA.com, which have interviewed Baker.

Baker says that he would eliminate the county’s 287(g) agreement, a position he highlights on social media and in campaign literature. “I know that we are all humans who deserve wonderful lives and I want to support that,” Baker told ConexiónUSA. com. Harrison may not want this issue at the forefront, said Felicia Arriaga, a professor of sociology at Appalachian State University and a volunteer at El Pueblo, an advocacy group for North Carolina’s Latinx community. Arriaga notes that Harrison hopes to avoid the fate of the sheriffs of Durham and Mecklenburg counties, whose immigration policies contributed to their defeats in May. “This is the most I have heard him not talk about the program,” she said. But she added that county politicians as a whole have been “very quiet” about 287(g) since its implementation in 2008, and that county-level law enforcement still demands more attention than it receives.

The Wake County jail has been under scrutiny this month since the death of a woman who died by suicide in detention. The News & Observer reports that the state as a whole could “be on pace to easily exceed the highest annual death toll for inmates in county jails.”

The opioid crisis “is not a problem we can simply arrest our way out of,” he wrote in an April op-ed, and he contrasts the prevailing emphasis on prosecution with approaches focused on treatment and public health.

Van Blarcum and Figueroa face each other again in November because Van Blarcum is endorsed by the Republican, Independent, and Conservative parties. Ulster County leans Democratic—it hasn’t voted for a GOP presidential candidate in 30 years—but Van Blarcum could win if he retains enough support among Democratic voters.

North Carolina: Wake County sheriff race struggles for media visibility, with 287(g) at stake

Federal courts have repeatedly ruled against local officials who hold people in jail beyond their scheduled release based on ICE “detainer” requests. In January, ICE and 17 Florida sheriffs launched a new bid to circumvent those rulings; they announced a new sort of agreement, which they claim will enable local officials to legally hold people suspected of being undocumented for 48 extra hours while ICE prepares to detain them. The ACLU disputes that the new mechanism changes the legality of ICE detainers. “The new scheme is simply a change in paperwork, with no relevant legal changes,” says the ACLU.

Among the 17 sheriffs who joined this partnership is Chad Chronister of Hillsborough County, which contains Tampa. A Republican who was appointed to this office by Governor Rick Scott in 2017, Chronister is now seeking a full term.

While Chronister’s cooperation with ICE has drawn protests, local leaders from both parties have rallied around the sheriff. A month after his appointment, in October 2017, Chronister held a campaign kickoff with prominent county politicians, including Democrats like Tampa Mayor Bob Buckhorn and State Attorney Andrew Warren. Chronister then joined ICE’s new program in January; Buckhorn and Warren have since reiterated their endorsements of Chronister.

Gary Pruitt, a former Tampa police corporal and Chronister’s Democratic challenger, told me on Monday that he would “definitely withdraw” from Chronister’s new partnership with ICE if he were elected. He said that the agreement implements a “dragnet approach” as federal authorities can target people on the local jails’ databases even if they didn’t “have somebody that they’re looking at.” “All you’re doing is screwing with people,” Pruitt said, noting that “the stigma of how we participated” makes communities distrust local law enforcement and endangers public safety.

The Appeal’s George Joseph wrote an article that details other issues in the Hillsborough County sheriff’s office, including its “troubling opacity regarding custody jail deaths.”

Oregon: State’s 30-year-old ‘sanctuary’ law is under threat

President Trump’s aggressive approach toward immigration enforcement is echoing in Oregon. On November’s ballot is Measure 105, a referendum that would repeal the state’s “sanctuary” law (ORS 181A.820).

Oregon adopted its sanctuary law in 1987 to prohibit local law enforcement from “detecting or apprehending” individuals over their immigration status. An impetus behind the law was to bar deputies from profiling people based on who they suspect might be undocumented. Repealing this law would expand local law enforcement’s ability to help federal immigration authorities arrest undocumented immigrants. Measure 105 is championed by the Federation for American Immigration Reform, a group that favors severe immigration restrictions.

The sheriffs of Oregon’s three largest counties (Multnomah, Washington, Clackamas) all oppose Measure 105; Washington’s sheriff, Pat Garrett, co-wrote an op-ed defending the “sanctuary” law in August. A group of sheriffs representing smaller, more rural counties endorsed repeal in August through a statement that ties illegal immigration to criminality; they write that immigration law-violations are “precursors to other crimes illegal immigrants routinely commit in their efforts to conceal their illegal presence.” Numerous studies contradict such a connection.

What is striking about this repeal push is that Oregon’s sanctuary law does not even affect local law enforcement’s ability to partner with federal authorities when it comes to people already jailed on grounds others than immigration. Oregon’s sheriffs can notify ICE when they detain foreign-born individuals—and Garrett himself engages in this practice daily, The Oregonian reported.

Many of the recent debates about how to restrict local cooperation with ICE (for instance in Minneapolis or Orange County, California) have focused on going an extra step and restricting local officials’ cooperation with ICE even within jails