Indiana Republicans Are Banning Student IDs for Voting

The new restriction, paired with Indiana’s stringent voter ID rules, is poised to make it much harder for many young people to vote in a state that already ranks near-last in turnout.

| February 26, 2025

Editor’s update: The Indiana governor signed this legislation, Senate Bill 10, into law on April 16.

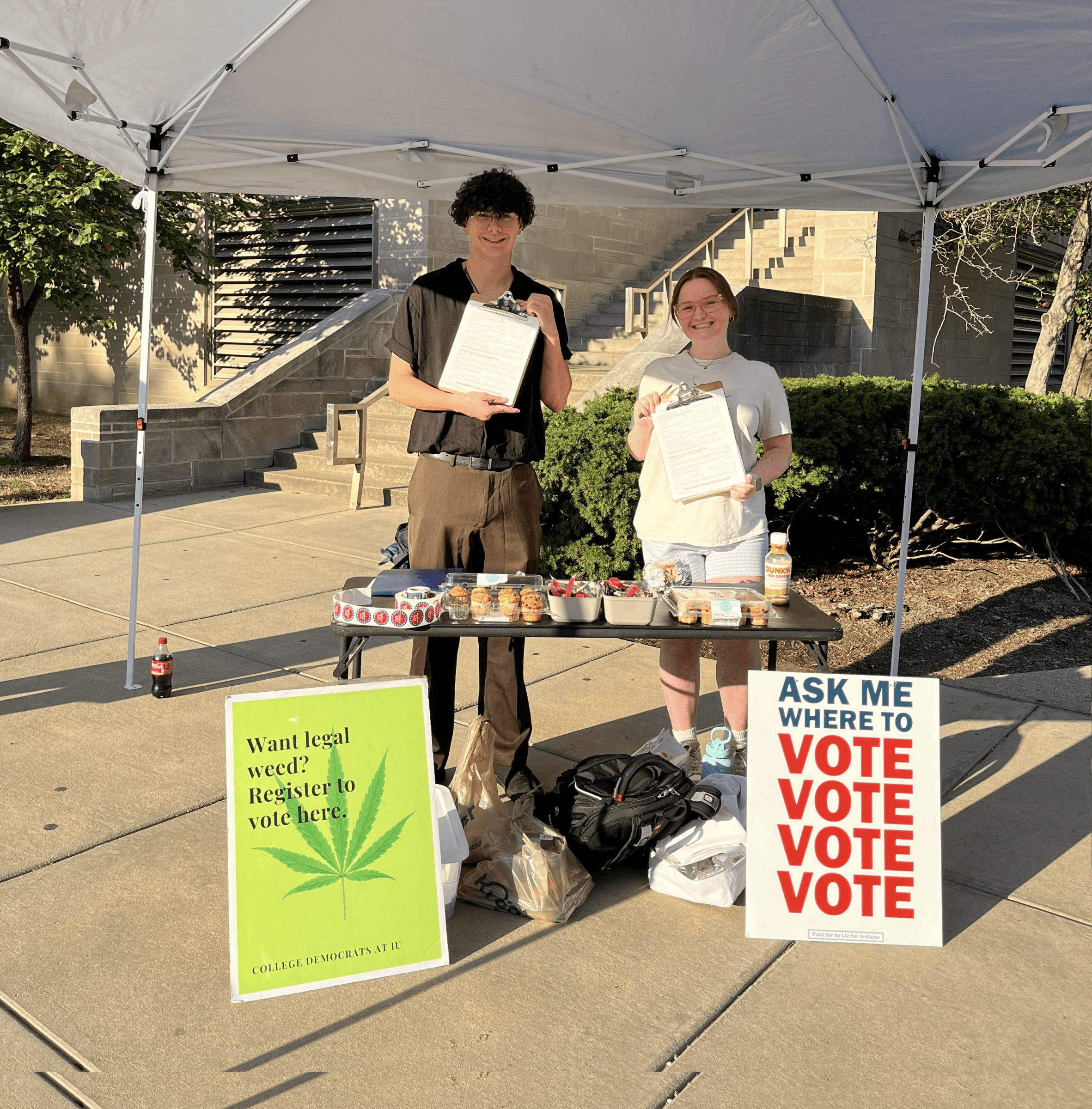

Daniel Jenkins has volunteered to boost voter turnout on Indiana University’s Bloomington campus since becoming a student there in 2022. Jenkins, now a junior studying political science, has spent years helping other students fill out voter registration forms and walking them through information about polling places and hours. He also reminds them they’ll need to bring an ID to vote. That last part, he reassures them, should be easy, since Indiana’s voter ID law allows state university students to present their campus IDs at the polls.

“That’s good enough for most people,” he says. “A lot of them will just happen to have it on them anyway.”

But Indiana may soon make voting much tougher for college students: Legislation banning the use of student IDs for voting passed the state Senate with near unanimous Republican support in early February and now sits with the GOP-run House.

Jenkins, who led voter registration efforts for IU Bloomington’s College Democrats during the 2024 elections, told Bolts that banning student IDs at the polls would add a significant barrier for many students who want to vote. If a student who just moved to campus before a fall election can’t vote with their university ID, and doesn’t already have another ID issued by the state of Indiana, they’d then need to trek to the closest BMV office miles from campus and supply documents that can be tricky for students to obtain—all during a busy season of classes and midterms.

Students are eligible to vote in Bloomington regardless of where they’re from. But in practice, “the passing of this bill would just make it almost impossible for out-of-state students to do so, especially if they don’t have a car,” Jenkins said. “And it’s definitely an issue for in-state students, too. Not all of us have driver’s licenses.”

Kylie Farris, the election supervisor in Monroe County, where IU Bloomington is located, confirmed that many local students rely on these IDs to vote. She told Bolts that her office doesn’t record what type of ID voters show, but she still estimated that two-thirds of people who cast ballots at the only on-campus polling place this November used a student ID.

Jenkins shared his concerns with lawmakers in late January by testifying against Senate Bill 10 in a committee hearing. Days later, the Senate passed SB 10 on a vote of 39 to 11. Every Republican supported it except Senator Greg Walker, who joined Democrats in opposing it.

“I think at best, it’s a misguided policy that is building on anti-student sentiment, and at worst, it’s a targeted form of voter suppression to try to make it harder for students to vote,” Jenkins told Bolts after the Senate passed the bill.

Voting rights advocates have now shifted their focus to the House, which reconvenes next week for the second half of the state’s legislative session. “I am hopeful that with continued grassroots pressure we will be able to kill SB 10,” said Julia Vaughn, executive director of Common Cause Indiana, “but it’s going to take a lot of work and some luck.” She hopes to persuade the House Speaker Todd Huston, who indicated some broad reluctance to overhaul election laws in early February. (Huston did not return a request for comment from Bolts.)

If SB 10 becomes law, it would dovetail with a long-running struggle for ballot access for college students in other parts of the country, like the constant fight to get or keep polling places on university campuses and conservative organizing to limit college voting. Cleta Mitchell, a prominent conservative lawyer who assisted President Trump’s efforts to overturn the 2020 presidential election, urged the Republican National Committee in a 2023 presentation to crack down on voting on campuses. And GOP-run states have adopted a string of changes in recent years to do just that, including barring the use of university IDs at the polls, restricting students’ eligibility to vote, and making it harder for students to prove residency.

Indiana would be the seventh state to require a photo ID at the polls while disallowing all student IDs, even if they’re issued by state colleges and universities, according to trackers maintained by the Fair Elections Center and by Voting Rights Lab. New Hampshire is currently debating a similar move.

Mike Burns, who researches voter ID laws nationwide for the Fair Election Center’s Campus Vote Project, suspects that the conservative drift of federal courts is emboldening some states to keep making their rules more harsh out of increased confidence the laws will survive lawsuits. “States thought that, if they wanted their voter ID law to withstand a legal challenge, it needed to be broad, but as more states get away with having stricter and stricter voter ID laws, now a lot of these other states are going back,” he told Bolts. “They ratchet down on what IDs are acceptable, and target particular groups of voters and make it harder for them to vote.”

Indiana adopted its current ID rules in 2005. Since then, voters need to present a photo ID at the polls; if they don’t have an ID on them, they can cast a provisional ballot but must quickly return to show election workers the requisite documentation for that vote to count. An academic study published in 2009 found that the new rules disproportionately affected people under age 30 and above age 70, as well as Black people, because these groups were less likely to have the forms of ID mandated by the law such as driver’s licenses or passports.

That matches many nationwide studies showing the disproportionate effect voter ID laws have on communities where higher rates of people lack photo IDs, such as Native voters, more transient residents such as students, and residents who are less likely to be driving.

Allowing university IDs can help at least some people easily overcome that barrier, but Indiana’s voter ID law already left out some students. It allowed students attending public universities like IU to vote with documentation provided by those schools since they’re state-issued IDs. But it still barred voting with IDs from private institutions, meaning students at Butler University or Earlham College already need some other form of ID to vote.

But now Indiana Republicans say that IDs issued by state schools should also be banned at the polls, arguing without evidence that they threaten election integrity and are a gateway to fraud. Senator Blake Doriot, the chief author of SB 10, has said student IDs issued by public universities are not “accurate” enough to be trusted in elections.

The secretary of state’s office, headed by Republican Diego Morales, has amplified Doriot’s point that student IDs are unreliable for use in elections and supported banning them at the polls. Morales, who won in 2022 after repeating false claims that the 2020 race was rigged against Donald Trump, was part of a nationwide “America First” slate of secretary of state candidates who ran on championing new voter restrictions borne of Trump’s unfounded statements about the 2020 election.

Doriot’s office said the senator was unavailable for comment when asked for instances in which student IDs have facilitated fraud. Morales’ office did not reply to a request for comment.

Voting rights advocates warn that, instead of catching fraud, the bill will effectively bar some Hoosiers from casting ballots.

“We all want secure, safe elections, but we want them accessible, and we want every eligible voter to be able to vote,” said Linda Hanson, president of the League of Women Voters of Indiana. “There are a number of [individuals] for whom the student ID is the only viable form of ID that they’ve got.”

Hanson lives in Muncie County, home to Ball State University, where her local league works with a team of students known as democracy fellows to bolster turnout. She said she suspects that SB 10 is less about election security than keeping young voters out of elections.

“This is singling out students as a target group that a certain percentage of our legislators do not want to be able to vote,” she told Bolts.

Federal courts for decades have protected the right of college students to say they’re residents of the location where they go to school and can register to vote there, so states cannot directly ban incoming students from doing so. Still, a mounting pile of restrictions can have that same practical effect, and some Republicans have said explicitly that they don’t want students who move from another state to vote locally.

Jenkins, the IU junior, defends student involvement in local politics. “For every single one of those years when you’re going to college, you’re dedicating a considerable amount of life to the city that you’re living in, the community that you’re a part of,” he said. “Even if they came from out of state, to tell them that they couldn’t vote here for four years up to that point is a little bit insulting.”

Even if conservative lawmakers question how college students vote, the U.S. census counts them as residents where they go to school; so when it comes time to draw congressional and legislative maps, their presence increases the political power of university towns, even if they’re originally from out of state. Vaughn, with Common Cause Indiana, also stressed that students who move from another state pay tuition money to Indiana and pay local taxes.

Vaughn and other Indiana advocates told Bolts they wished that state lawmakers would focus instead on reforms to boost participation among Hoosiers. The current picture isn’t pretty: Indiana ranked 50th in voter turnout in the 2022 cycle, out of the 50 states plus Washington, D.C., according to the biannual Indiana Civic Health Index’s most recent installment.

And turnout of young voters in Indiana was well under the national rate in both 2020 and 2022, according to an analysis by a Tufts University initiative that studies youth engagement.

Asked what he’d want to change at IU Bloomington to make voting easier, Jenkins called on his local county officials to set up at-large vote centers.

Some counties in Indiana already use such centers, which means that registered voters can cast a ballot at any polling location in the county. But Monroe County requires voters to show up at their designated precinct.

Many IU students are assigned polling places that aren’t on campus and sometimes difficult to access without a car, and they must be sure they find the right polling place.

Jenkins says students assigned off-campus polling places often show up to the one on campus thinking they can vote there, only to wind up casting a provisional ballot that gets tossed officials review and confirm they went to the wrong location.

Farris, the Monroe County supervisor, told Bolts that 300 people cast provisional ballots in November at IU Bloomington’s polling center, at the Indiana Memorial Union Building. Not a single one of those provisional ballots counted, she said.

Monroe County leaders have explored switching to at-large centers but still haven’t adopted the approach.

Tippecanoe County, home to Purdue University, the state’s second largest public university after IU Bloomington, already uses at-large voting centers. But in 2024, Purdue lost its sole on-campus polling location for Election Day. The county’s decision provoked an outcry against local officials and university leaders, with some students and community members accusing them of trying to lower participation among local students.

Another way to boost voting on Indiana’s campuses would be to allow people to register to vote as late as Election Day, said Vaughn. Twenty states, plus Washington, D.C., already allow this. Instead, Hoosiers this past fall had to register to vote by Oct. 7 to vote in the presidential election; that gave campus organizers just a small window to get newcomers on the rolls.

“In a state like Indiana, which has such abysmal civic participation statistics, we should be welcoming all voters, all sorts of participation,” Vaughn said. “We should welcome them and make it easy for them to participate in our elections.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.