Public Defenders Look to Grow Their Presence on the Bench in Los Angeles

Hoping to reform county courts, three public defenders are running for judge this fall. They want to build on the success of one candidate in 2022 and another in March.

| July 15, 2024

Last fall, Los Angeles started using new bail guidelines that required judges to set bail at affordable rates, but you wouldn’t necessarily know it from sitting in court all day. In conjunction with her pretrial justice clinic, UCLA law professor Alicia Virani spent part of October 2023, the first month LA’s new bail schedule was in effect, observing court proceedings that seemed as quick and rote as an assembly line at LA’s largest courthouse. “They’re churning out pretrial decisions like a factory,” she told Bolts.

Alongside volunteers from Courtwatch LA, Virani and her students witnessed higher bail amounts, and lower rates of release without having to pay bail, for Latinx defendants compared with Black or white defendants. “Various court watchers observed at [the main courthouse] what they felt was like a notably hostile environment towards Latinx folks who were in custody,” Virani said. The clinic and Courtwatch LA went on to publish their observations in a joint report, finding that cash bail was set in 68 percent of the over 200 cases they observed, and the median amount set was $100,000, double the statewide average and far more than the average Californian can afford. Judges are “just blatantly ignoring the law that they’re supposed to follow,” Virani told Bolts.

Choosing to set bail so high that there’s no hope of paying can mean the loss of a job, or a defendant’s ability to care for their children. These decisions can also carry life-altering consequences in a jail system where someone dies nearly once a week. But judges ultimately have the final word, and there are few mechanisms to challenge their decisions. “When a judge denies bail in a situation where it should not be denied, or sets bail in a situation where it shouldn’t have been set, we’re sort of stuck with that decision,” Ericka Wiley, a public defender in Los Angeles County, told Bolts.

For some organizers, bringing change to Los Angeles’ court system demands more than just updating its rules. They think that the county needs judges with a different approach, one more attentive to the pitfalls of incarceration—and in Los Angeles, that takes winning judicial elections. In 2022, a slate of four attorneys with a background in public defense or civil rights ran for judge with mixed results: One of them, Holly Hancock, won her election, while the others lost to opponents who followed the more conventional prosecutor-to-judge pipeline.

A new set of public defenders is trying again this year. One, Kimberly Repecka, already won her seat in the March primary and will join Hancock on the Los Angeles Superior Court. Three others still face tests this fall: Wiley, as well as George Turner, Jr. and La Shae Henderson, are bidding to replace three retiring judges. In the March primaries, each grabbed one of the top two spots and advanced to the November runoffs.

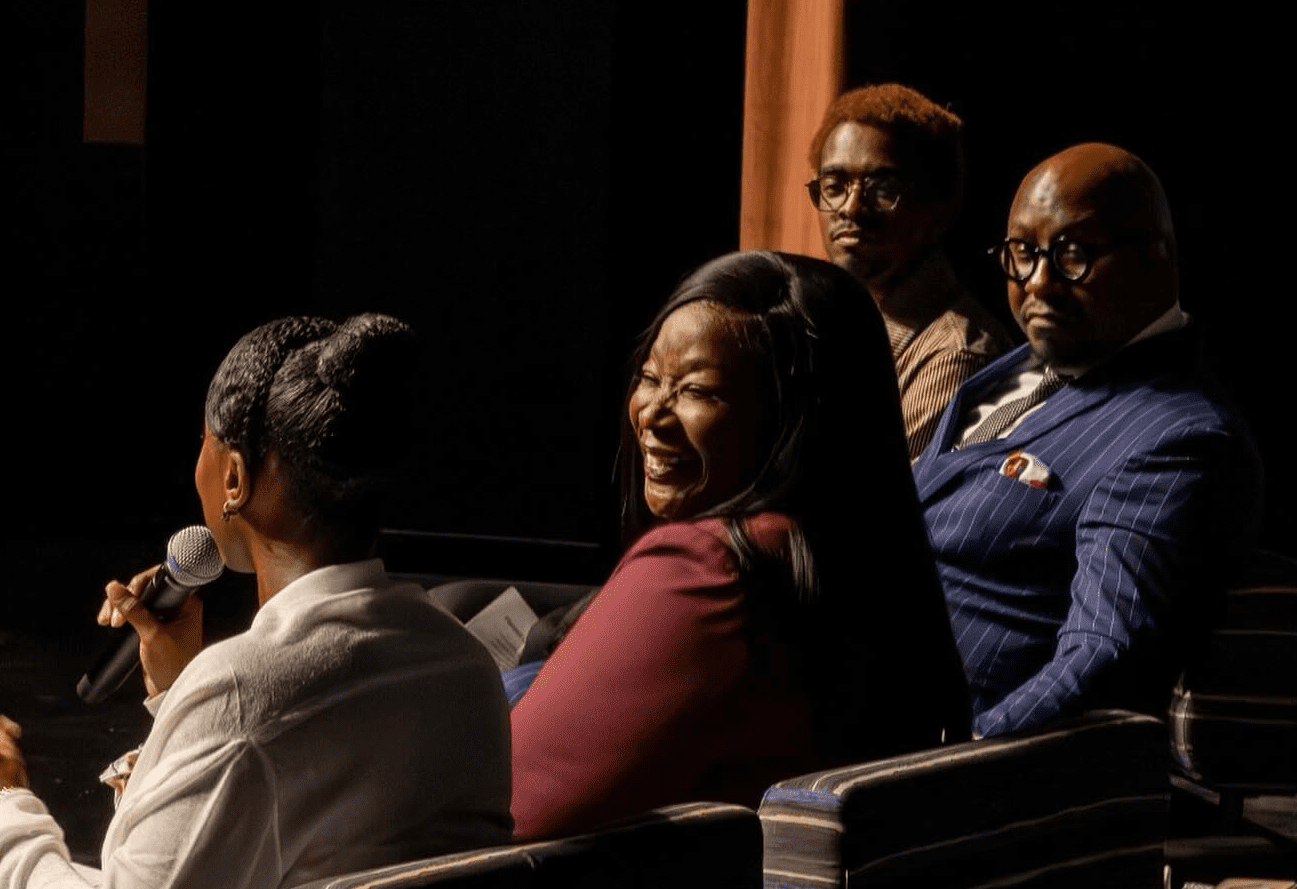

These candidates are running in separate countywide elections. But they’ve delivered similar messages. Last summer, they all participated in a judicial election bootcamp run by La Defensa, a community group that recently took over Courtwatch LA, and by the organization LA Forward. Now on the campaign trail, they insist that the job of a judge should be more about finding creative solutions to foster rehabilitation than doling out punishment.

“We have over a half a century of experience in this apparatus, and we know that it doesn’t work,” Turner told Bolts. “It didn’t make sense 20 years ago and it doesn’t make sense now that you would have thousands of people in Los Angeles County in custody [who] haven’t been convicted of anything. It didn’t make sense then and it doesn’t make sense now that we would put someone in a cage without figuring out what led to the conduct.”

In the runup to the primary, Henderson, Turner, and Wiley joined forces, appearing at events together and forming an informal slate with a joint website and branded social media. Like their predecessors on the 2022 slate, they called themselves “The Defenders of Justice.” Prominent local progressives, like Los Angeles Controller Kenneth Mejia, endorsed all three candidates.

Repecka, who won her seat in March after challenging an incumbent judge who had received a rare public rebuke from the state judicial oversight agency, did not join this “Defenders of Justice” grouping; she did, however, make campaign statements signaling that she broadly shares their beliefs on how the judiciary might work to reduce mass incarceration. Turner and Wiley are still campaigning as a team for the general election. But Henderson has since chosen to run her campaign separately and no longer appears on “Defenders for Justice”-branded material, though she told Bolts she still supports their mission.

In November, Henderson and Wiley will face current prosecutors Sharon Ransom and Renee Rose, respectively. Turner is running against Steve Napolitano, a parole board attorney and Manhattan Beach city council member.

In separate interviews, Henderson, Turner, and Wiley all said that they chose to run in part because they found themselves frustrated by judges’ reluctance to consider pre-trial release or implement alternatives to incarceration for their clients. “We’re finally starting to get to a place where the laws are starting to get more and more in tune with common sense and what is morally right,” Turner told Bolts. But, he said, “when you walk through the average courtroom, it hasn’t changed.” They argue that their experiences position them to implement reforms that California has adopted over the last decade—laws that allow the sealing of criminal records, expand access to mental health diversion, and permit judges to reduce incarcerated people’s sentences.

“As a public defender, when you go to that court every day, you see whether it’s being implemented,” Henderson said of the state’s new reforms. “That’s where the fight is, is taking it from off of the page of a book and getting people to really start to put it to action.”

Win or lose, these public defenders are only running to take over just a few of the over 400 superior courts seats that adjudicate Los Angeles County criminal cases. While any change to how judges approach defendants will be incremental, Holly Hancock’s new daily routine illustrates what that sort of piecemeal scale change looks like in one courtroom.

These days, Hancock, the lone winner from the original “Defenders of Justice” slate, presides over a misdemeanor court in Inglewood, where she most commonly sees DUI and domestic violence cases. She says her background as a public defender has shaped her use of judicial discretion and equipped her to take a more holistic approach to the defendants—one that incorporates an awareness of mental health and addiction issues, as well as an appreciation for how the collateral consequences of a criminal legal interaction can derail someone’s life. “It’s really in every area, at every step,” Hancock told Bolts. “I’ve always said it gives me an opportunity to be actually more even handed.”

At arraignments, Hancock said she makes sure to review what leeway she has on bail. When considering a defendant’s ability to pay, she’ll sometimes let them post the cash they’re able to raise directly to the court, in order to avoid the exorbitant interest rates that bondsmen charge. ”A lot of times it’s the family members or the girlfriends [who pay], it’s not even the person who’s in jail,” she said. “Grandma is now on the hook, or her house is on the hook. So I’d rather, if they can get the cash together, just post the cash.”

Whenever possible, Hancock said, she diverts people toward programs that help them avoid a criminal conviction if they complete certain steps, like community service. She also refers people who need support with housing and other services to the county’s new Justice, Care, and Opportunities department, an agency created as part of a county-level effort to implement a “care first, jails last” approach toward crime.

“You can work so many different things to assist people that don’t have anything to do with incarceration,” Hancock told Bolts about the misdemeanor cases she handles.

The three public defenders currently in contention for a judicial seat told Bolts they would take a similar approach, prioritizing alternatives to incarceration and viewing jail or prison time as a final course of action rather than a default. “I’ve never seen someone come out of prison and be better overall… It’s a devastating experience and should be a last option when all others have failed,” Wiley said.

Henderson said she’d like to see the principles of the youth justice system—rehabilitation and redemption over punishment—applied to adults well. “We kind of have this mindset that once you’re 18, you’re on your own and you messed up. But if we could bring more of that restorative style, even for the adults, I think it would prevent more recidivism,” she told Bolts.

Henderson and Wiley’s opponents, Ransom and Rose, are both line prosecutors with the LA District Attorney’s office. Neither responded directly to a request for an interview, and a campaign consultant representing both candidates did not provide responses to a request for comment. On her website, Ransom touts her work in the DA’s mental health unit, writing that her “focus on community empowerment diverges from traditional prosecution.” Rose currently works as the supervisor of the DA’s elder abuse unit. Her website stresses that she has worked in many units of the DA’s office, “dedicating her entire legal career to the protection of crime victims.”

Napolitano, who faces Turner, told Bolts via email that he too supports alternatives to incarceration when appropriate. If elected, he said he’d “take advantage of work programs, community service programs, and educational programs for youth offenders as alternatives to juvenile hall which too often hardens kids against the system instead of them benefiting from it.”

Napolitano, who has worked as a parole hearing representative, administrative hearing officer, and local politician, added that he thinks Los Angeles would benefit from judges who have done multiple things in their careers, rather than career public defenders.

“We need more judges with diverse backgrounds who know our communities, who have worked with both victims and criminals, and who have the experience to know what works and what doesn’t,” Napolitano said.

The public defender candidates, though, believe that what sets them apart is the depth of their experiences representing indigent defendants.

Early in his career, Turner worked in the Los Angeles County public defender’s juvenile division in Inglewood, the predominantly Black and Latinx city where he grew up. “I would see kids who are going through the same sort of issues that I went through as a public school kid growing up in the city,” he recalled. “And I also saw the system not address their needs and kind of put them on a pathway to destruction in some cases.” Given these experiences, Turner said he feels that putting young people in an adult prison makes no sense from a developmental perspective.

“I’ve been a victim myself of multiple crimes,” he told Bolts. “I have friends and family who have been killed. What happens in the courtroom doesn’t make you feel any better.”

Like Turner, Henderson, who recently left the public defender’s office to set up her own criminal defense practice, worked in the juvenile division earlier in her career. She says she frequently watched judges treat Black and Latinx youth harshly, with little regard for their age.

“That’s an opportunity to mentor, that’s an opportunity to speak into that kid’s life,” she told Bolts. “What would it look like if our courts facilitated that?”

Despite the recalcitrance of some judges and line prosecutors, a lot has changed in Los Angeles courts in the last decade. A broad effort to correct for some of the injustices of the tough-on-crime era has brought reforms at various levels, from a state supreme court decision that held that it is unconstitutional to imprison someone because they cannot afford bail, to ballot measures like Proposition 47, which downgraded some felonies to misdemeanors, to Los Angeles’ new bail schedule and the election of reform-minded politicians like DA George Gascón.

These changes have already refashioned the role of judges in LA. Hancock noted that in her court, prosecutors are “by and large, far and away, not asking for incarceration on the misdemeanors,” meaning that judges who preside over misdemeanor court largely aren’t even in a position to approve jail time—nor do they have to go out on a limb to reject it.

In theory, judges are also responsible for evaluating whether to transfer 16- and 17-year-olds to adult criminal court. But this only comes into play if prosecutors propose that move, and Gascón initially pledged that his office never would. Though he has walked back that blanket ban on prosecuting juveniles as adults, there have nonetheless been few opportunities for LA judges to make these determinations: Only 10 cases were recommended for transfer between when the DA took office in December 2020 and the end of January 2024.

But this landscape may shift again this year. Repecka and any of the public defender candidates who wins their election this fall could take their seat in a different Los Angeles, one where prosecutors are pursuing notably harsher outcomes and where judges have more authority to crack down on low-level offenses.

Gascón faces a difficult reelection bid against Nathan Hochman, a former Republican candidate for state attorney general who has said he’d undo many of Gascón’s reforms. Hochman has vowed to seek harsher charges and sentences, criticized Gascón for being too lenient toward minors, and indicated he may seek the death penalty again, a practice that Gascón forbade.

A win by Hochman in the DA race may lead to a growth in the number of transfers to adult court or in the sorts of penalties sought for misdemeanor cases. Whether judges think it’s appropriate to treat a minor as an adult or order jail time for a misdemeanor could matter more under a different DA. And if line prosecutors are given more freedom to seek lengthy sentencing enhancements than under Gascón, judges would also have more occasion to impose significantly longer sentences.

Voters across California will also be deciding this fall whether to walk back Prop 47, the 2014 measure that helped the state lower its prison population from historic heights, but which has been much maligned lately by conservatives and business organizations who hold it to blame for retail theft. Under the terms of the ballot measure, judges would have significantly more discretion to punish defendants more harshly, though they’d retain the ability to send someone through the diversion process instead.

Turner noted the strangeness of running at a time when the ferocity of the backlash can feel at odds with the day-to-day work.

“We’re almost in bizarro world, because if you look at the statistics, crime is down,” he said, a reference to police data that show robberies, homicide and violent crime rates in LA are lower than several years ago. “But part of the reason why I’m running and part of the reason why I am so vocal and active about these sorts of reforms, is because I don’t believe that [they’re] just a fad.”

Turner ultimately takes the long view, stressing that calls for reform have come out of the decades-long failure of punitive solutions. “We can actually change these institutions,” he said. “And we should.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.