Auditing the Status Quo in Los Angeles

Kenneth Mejia designed his bid for city controller to engage Angelenos in how their money is spent on policing.

Piper French | August 17, 2022

Editor’s note (Nov. 11, 2022): Kenneth Mejia won the election for controller in the Nov. 8 election.

Last summer, a billboard with an unexpected image graced the intersection of Olympic and Crenshaw boulevards in Los Angeles. Near advertisements for personal injury lawyers and recently released television shows hung a bar chart illustrating how the city spends the public’s money. A green rectangle representing police spending under the mayor’s proposed 2021-2022 budget dwarfed the numbers for housing and homelessness, stretching all the way to the right-most side of the frame to represent over $3 billion. The caption asked simply: Is Mayor Garcetti’s Budget Good For You?

The billboard was put up by Kenneth Mejia, the frontrunner in the race for Los Angeles city controller. Mejia has taken a creative and unconventional approach to campaigning for a position that is habitually misunderstood and hardly ever considered exciting. In running for the elected office responsible for audits, financial reporting, and the city’s payroll, he has used public records requests to glean data on everything from LAPD traffic stops to the residence of every LA city employee, presenting the information in easy-to-use online platforms, plastering it on billboards like the one at Olympic and Crenshaw, and promoting it relentlessly on social media.

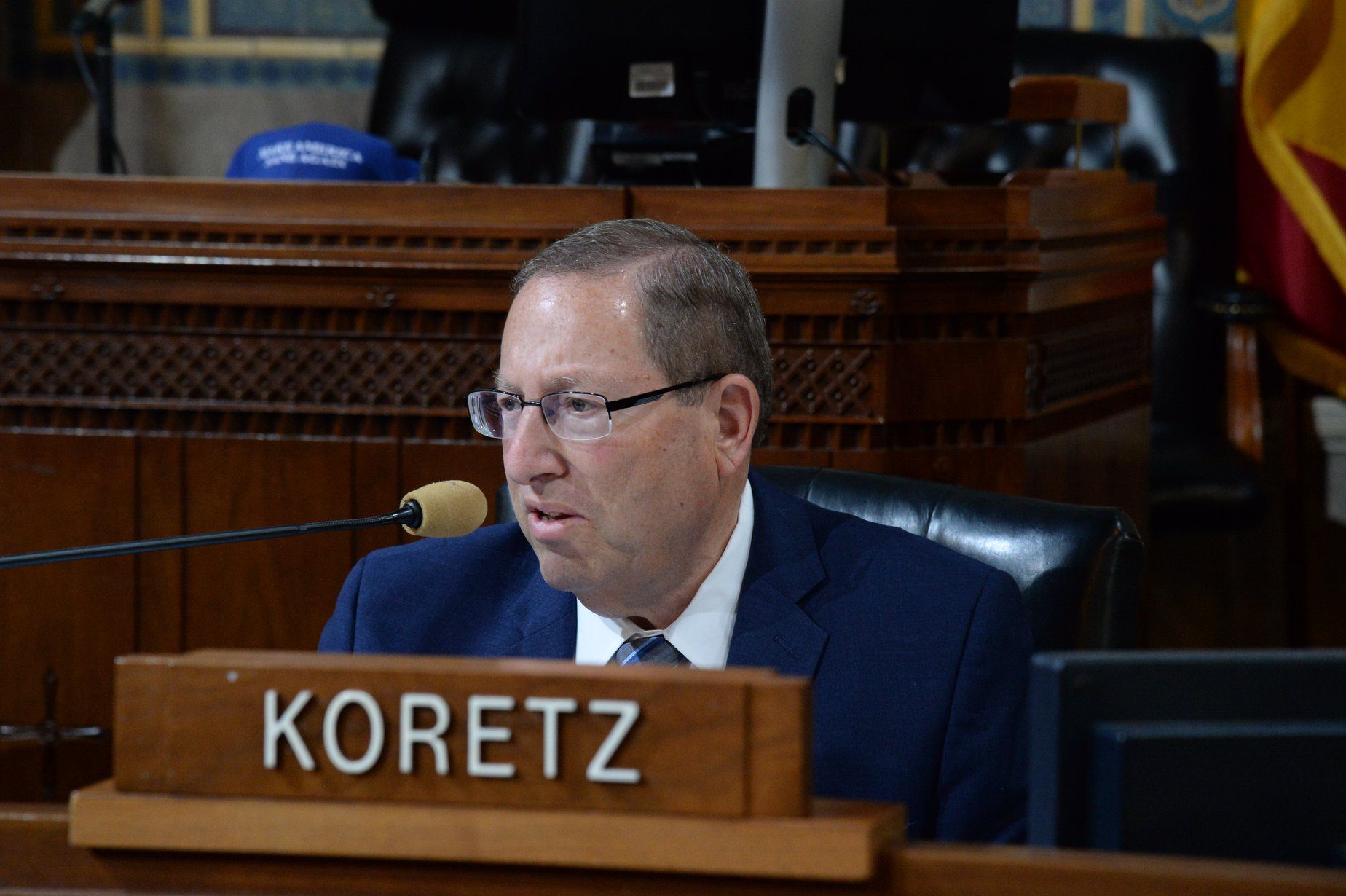

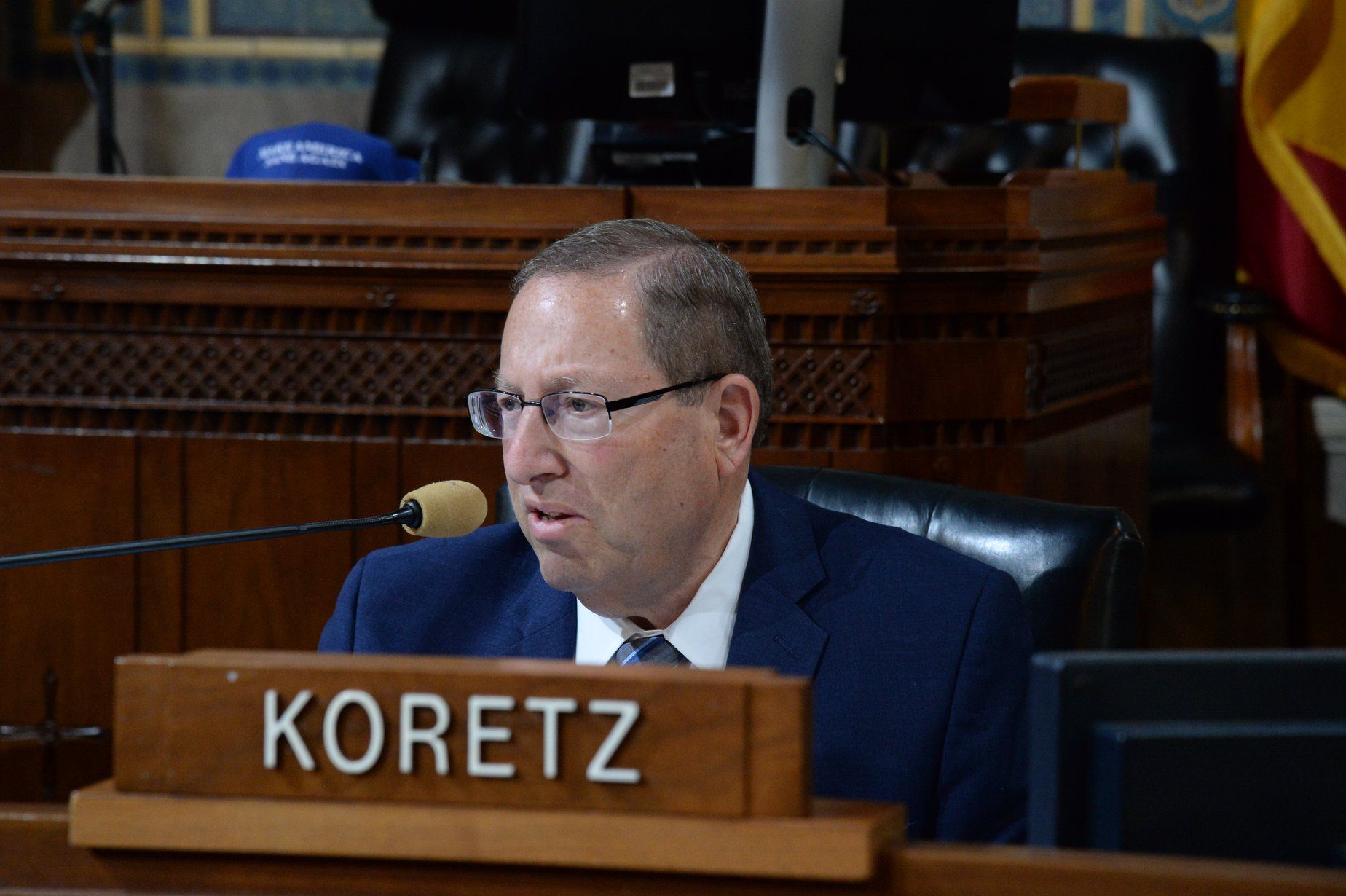

Thus far, these efforts have paid off: Mejia won the endorsement of the L.A. Times editorial board, which commended him for using his campaign “to demonstrate the kind of transparency-and-data-driven controller he would be.” In June, in a crowded, seven-person nonpartisan primary, the 31-year-old candidate finished first with 43 percent of the vote, more than 100,000 votes ahead of longtime city council member Paul Koretz. Mejia and Koretz are now set to face off in a November runoff.

Mejia’s campaign strategy builds on the efforts of groups like the People’s Budget LA, a coalition of organizations led by Black Lives Matter LA that argue that the city’s spending priorities should look very different. His approach—to visualize and publicize the chasm between the city’s current budget and demands for reform coming from the community— follows the logic behind campaigns like the People’s Budget Report, released during the George Floyd uprisings in mid-2020, which polled thousands of residents and juxtaposed their budgetary priorities with Mayor Garcetti’s “Justice Budget” proposal.

This sort of campaign has deep roots in Los Angeles: In 2003, the nascent Youth Justice Coalition, which is now a member of People’s Budget LA, mounted a “dollar for dollar” campaign with the goal of massively expanding funding for youth centers, intervention workers, and jobs. “That was essentially a youth-led campaign to urge city officials to invest the same amount of dollars they do into law enforcement and criminalization spending into youth development,” said the group’s media coordinator, Emilio Zapién.

Meijia shares the fundamental goal of these campaigns: to engage voters in the city’s budgetary process, reframing something commonly viewed as abstract and opaque as a willful process of resource allocation—one that affects everything from what neighborhood you can afford to live in to where in the city you’re most likely to get arrested.

“I’m hoping that we can have a more transparent LA, especially with funding, and that’s what I want to bring as city controller,” Mejia told Bolts. “Like, nothing’s hidden, you can’t hide it. You’re going to show it and you’re going to explain why you did it.”

To those who would dismiss him as just an activist, Mejia has a quick rejoinder: he’s also a certified public accountant, a qualification that few city controllers possess. “In the past, the controller position has been used as a placeholder position for career politicians who just need a job,” Mejia told Bolts. “That’s why a lot of people don’t know where their money’s being spent or if it’s being used effectively or efficiently.”

Francine McKenna, a lecturer in financial accounting at Wharton who also maintains a newsletter about auditing and accounting issues, says it’s much more common for city controller candidates to be politicians looking for a stepping stone than actual financial professionals. “I can’t remember anybody ever running a campaign saying, ‘I’m actually an accountant with a CPA and I know how to do this stuff,’” McKenna told Bolts.

McKenna first found out about Mejia’s campaign on Twitter. In an interview, she praised the candidate’s online engagement and use of public records to inform residents about the city’s payroll, affordable housing, LAPD arrest and homelessness criminalization zones, and more. “He’s using the skills and the background that he brings as a CPA, as someone who’s worked in public accounting and consulting,” she said. “He’s bringing those to the table and saying, here are all the ways that we think citizens should have greater transparency in terms of where the need is—and how that compares with where money is spent.”

Mejia possesses a somewhat unique background, having worked both as an auditor for the massive accounting firm Ernst & Young and as a tenants rights and housing activist. At 31, he has already run for national office twice, on the Green Party ticket, before deciding to re-register as a Democrat and focus on local electoral politics. “Everything that I cared about—homelessness, housing, policing, the environment, transportation—it was like, ‘oh, this is all on the local level,’” he recalled.

If Mejia’s third bid for office proves successful, he will occupy a strange place in Los Angeles politics. “At its core, the controller has an immense responsibility that’s probably second only to the mayor and the city attorney—but at the same time, it has extremely limited power.” said Rob Quan, an organizer with Unrig LA, which works against the influence of money in politics locally. The controller cannot investigate other elected officials. The office also can’t set its own budget, and can’t in any way compel the rest of the city government to accept its recommendations. The roughly 130-person department is chronically underfunded. According to Jeremy Oberstein, the former chief of staff to current controller Ron Galperin, much of its auditing resources are taken up performing mandatory, time-consuming reports on the Department of Water and Power and the city’s airports and sea port.

Quan predicted that it might be difficult for Mejia to completely square his big-picture activist mindset with some of the realities of the position. “I think it’s pretty safe to say there’ll be that tension there,” he said.

But despite these limits, the city controller does have one key arrow in their quiver, Oberstein said: the discretion to perform an audit “at any point.” The vast, sprawling city budget—nearly $12 billion for the upcoming fiscal year—is theirs to examine, sift through, and hold up to the light. And while city controllers don’t have the ability to enact policy, their reports can still influence public discourse and potentially translate into change.

Ultimately, the job is quasi-journalistic in both its emphasis on investigation and communication, as well as its indirect ability to influence outcomes, McKenna says. “You have to find a way to communicate sometimes difficult information or information that seems technical or seems kind of narrowly focused. You have to find a way to say: this is important.”

Quan agreed that the credibility and persuasiveness of a city controller’s reports have everything to do with the level of influence the position can wield. “Your audits can just be headlines, or they can translate into real policy change,” he said.

Mejia acknowledges the limitations of the office but says he hopes to use his audits to motivate constituents to speak up for political transformation. “We don’t have any policy-making power—we can’t change anything, pass rent control, we can’t stop evictions,” Mejia said. “Our power as controller is we provide data and the facts and the numbers for people to use. And then they are the ones who push the policymakers to make systemic change.”

One critical element of the job is the ability to reach people where they’re at. Oberstein stressed that Mejia is not the first to creatively visualize data—Galperin’s office has won awards for its work on data transparency. From the perspective of Youth Justice Coalition’s Zapién, however, Mejia has done a better job getting it into the hands of a wide array of people.

“My role as media coordinator is to be able to collect information that is going to be accessible to our folks, and share with them in a way that feels accessible and not intimidating or overwhelming or confusing—because these systems are designed to be complex and confusing, so that our people don’t feel like they have access,” Zapién told Bolts. “Are you sharing things in a way that it’s accessible to the people doing the work on the ground, regardless of whether we agree with you fully politically or not?”

Zapién noted that he often screenshots Mejia’s resources and sends them to colleagues. They’ve proved useful tools for illuminating the budgeting decisions behind young people’s daily experiences: why LAPD harasses them on the way to and from school, or why they only have only one youth center. “When we actually look at the numbers,” he said, there’s a powerful connection between how the city chooses to spend its money and the outcomes for its residents: “Of course, what do we expect to happen when we’re spending all this money on law enforcement and lockups and not in youth development?”

Mejia’s campaign is working on creating more campaign resources to add to those he’s already released. Next up is a database on the most expensive lawsuits the city has paid out, a map of park inequity across LA, and a big report on the LAPD—“so that people can have a one-stop shop on understanding, like, where the hell’s my $3.2 billion going?” the candidate told Bolts.

“At the end of the day, the controller is—by charter—a job that is open to redefinition,” Oberstein said. “The goal of the job, in my mind at least, should be to drive lasting change. And you do that by creating relationships and speaking truth to power.”

On that matter, the two runoff candidates take opposite approaches. Koretz, Mejia’s opponent in November, has campaigned as an insider, touting his close relationships at City Hall. Mejia flips that logic on its head. “As an outsider and a CPA, I can hold people accountable,” he told Bolts. “We don’t owe the establishment anything because we’re not part of it to begin with.”

In recent weeks, the two candidates’ diametrically opposed relationships to the status quo have boiled over into open conflict. Mejia is a sharp critic of the city’s approach to homelessness, which is characterized by widespread criminalization. Koretz, meanwhile, has been an architect and staunch defender of that approach. His campaign did not respond to a request for comment.

Mejia’s website recently posted a map and analysis of the city’s anti-camping policy, 41.18, showing that unhoused people would be banned from sitting, sleeping and storing belongings in about 20 percent of the city under an expanded version of the law. This statistic has pushed public debate on the issue, quickly becoming a talking point repeated by activists and local media alike. At a city council meeting on Aug. 9 to vote on the matter, members of the Services not Sweeps Coalition, which has a good deal of overlap with People’s Budget LA, disrupted the event, testifying vociferously to the law’s inhumanity. “I just want help,” one unhoused woman sobbed.

Mejia was there alongside them. “We’re here at City Hall today to support our unhoused neighbors,” he tweeted. (The candidate has downplayed his involvement with the People’s Budget LA, telling Bolts, “our campaign’s relationship is just providing financial information about the city.”) After protestors were forced out of the chamber by police, Koretz blamed his opponent, saying: “Just because Kenneth Mejia and his band of anarchists tried to break up two different meetings, we’re not going to stand for it. We’re going to take the action that we need to take.” The city council ultimately voted 11-3 to go ahead with the expansion.

One of Mejia’s central goals is to audit the city’s sweeps of encampments and other ways officials have criminalized people who sleep on the street. “I think what you’ll find is tens of millions of dollars being spent on these sweeps—and you’ll notice that the performance metrics of getting people housed from the sweeps are terrible,” he told Bolts. “I’m hoping that we can show just how much the city has failed on tackling homelessness.”