Pop-Up Voting Centers Bring the Polls Directly to Unhoused Angelenos

Nationwide, unhoused people have some of the lowest turnout among all voters. Los Angeles County is trying to change this with flexible polling centers that meet people where they are.

| December 5, 2024

Michael Barnett left the presidential portion of his ballot blank on Nov. 5. The 66-year-old didn’t come to the James Wood Community Center in Los Angeles to choose between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump; instead, he was much more interested in down-ballot races related to policing, healthcare, and housing that would impact Skid Row, his community of nearly a decade.

Barnett worried that if Los Angeles County’s progressive District Attorney George Gascón lost to opponent Nathan Hochman, policing could increase in the downtown Los Angeles neighborhood home to thousands of unhoused and formerly unhoused residents.

“It’s going to be horses back down here,” said Barnett, alluding to the Los Angeles Police Department’s mounted unit. “It’s just going to incarcerate a lot of people, people are going to be going to jail for petty stuff.”

Homelessness was on the California ballot again this year, as it is increasingly playing a role in the state’s politics. A February 2023 survey by the Public Policy Institute of California found that Californians “are most likely to name ‘jobs, the economy, and inflation or homelessness’ as the most important issue for the governor and legislature to focus on. In Los Angeles County, nearly three-quarters of residents said homelessness “is a big problem in their part of the state.”

Measure A was the clearest referendum on homelessness policy in LA County this year. The measure asked voters whether to extend and double the county’s quarter-cent sales tax that funds services and housing for people experiencing homelessness. And even in less direct ways, LA’s elections shape how homelessness is felt, from local and state ballot measures related to rent control and affordable housing to races for local elected officials who make decisions on the frequency and locations of sweeps, and how homelessness will be criminalized within their jurisdiction.

But as a voting bloc, people with lived experience with homelessness like Barnett are underrepresented at the ballot box. More than 1 in 5 people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. live in Los Angeles County, and the county’s unhoused population of over 75,000 equals a constituency bigger than most of the county’s 88 cities. These potential voters could inform state and local efforts on homelessness by choosing which elected officials, policies, and programs might best serve them—but structural barriers make them less likely to vote. Data on voting among people experiencing homelessness is scarce, but one estimate found only about 10% of unhoused Americans vote each year.

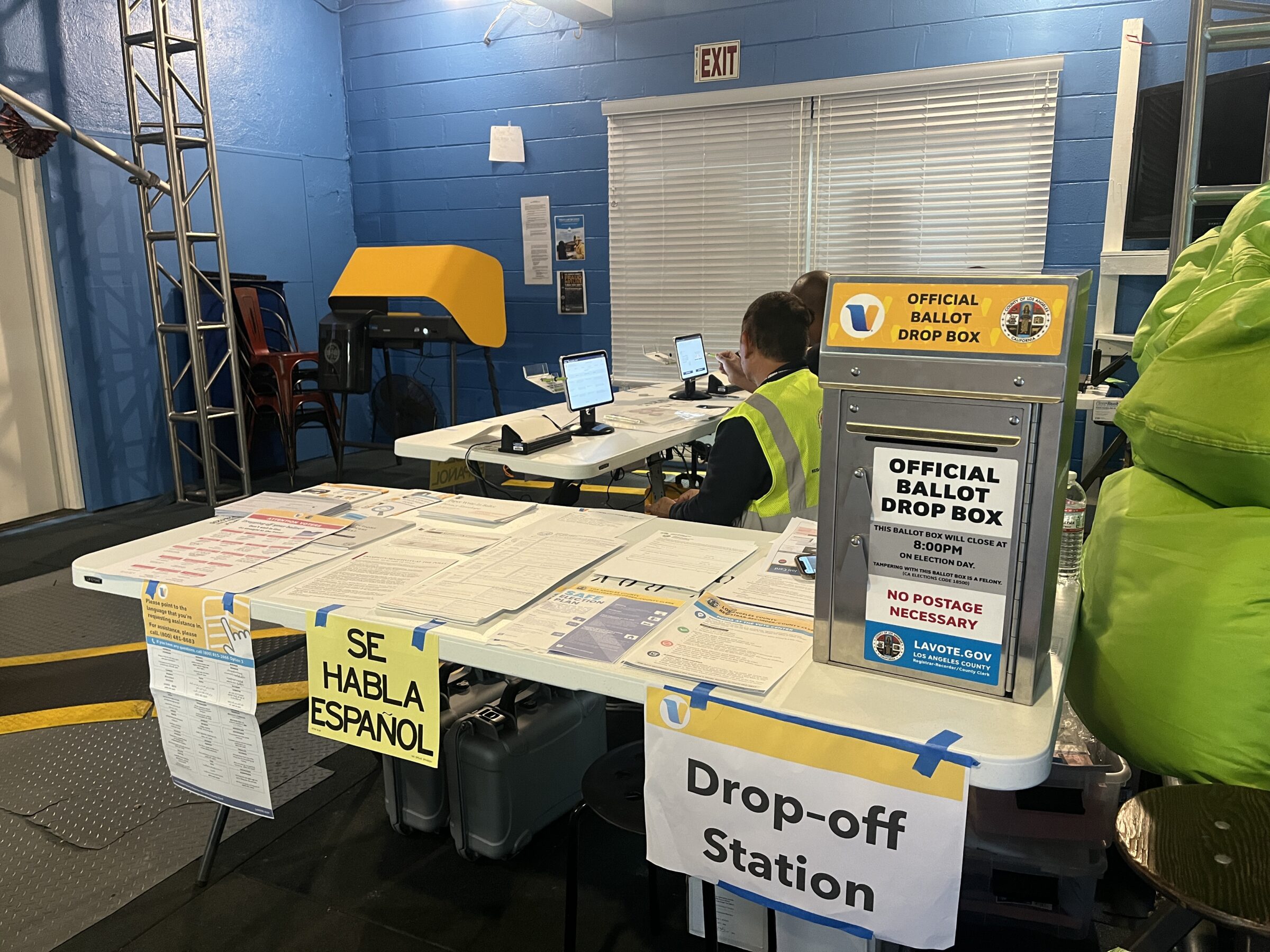

Los Angeles County is actively working to change this trend with the Flex Vote Center Program, which brings voting directly to shelters and service centers for people experiencing homelessness. The hope is that bringing the polls to locations where unhoused people are already receiving services will reduce one barrier to voting.

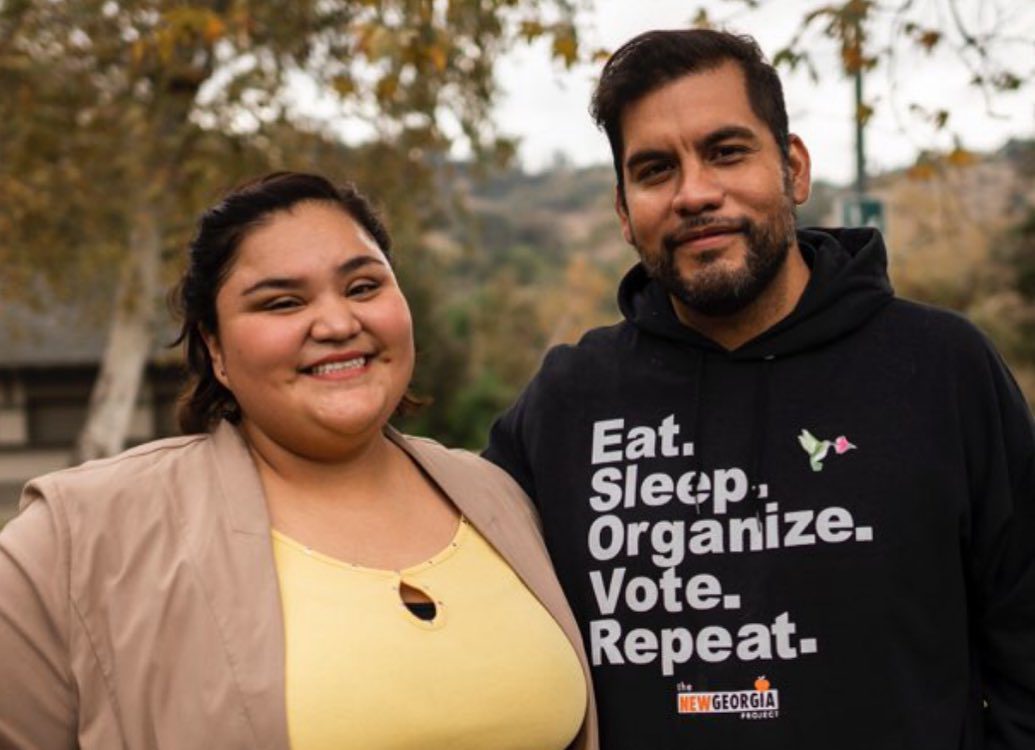

“Voting is the least of their concerns,” said Angel Agabon, 24, who recently experienced homelessness himself and voted for the first time this year at My Friend’s Place, a drop-in center in Hollywood for young people experiencing homelessness. “They got more shit to worry about than voting… They don’t know where they’re going to stay tonight, they don’t know what they’re gonna eat, they don’t know when they’re next meal’s gonna be, so voting, it’s not their primary concern, especially when they’re in this situation.”

The hope is that with Flex Vote Centers, people can go to places where they can get these basic needs met, and also participate in civic life. My Friend’s Place hosted a Flex Vote Center on Monday, October 28, one of 93 sites that the Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk opened this year. The County Clerk launched the program back in 2020 along with other efforts aimed at making voting easier, especially among underrepresented groups such as voters experiencing homelessness, voters with disabilities, voters residing in assisted living homes, and geographically isolated voters. Most Flex Vote Centers are open for one or two days during the two weeks leading up to the election, while the county’s regular vote centers are either open for 4- or 11-day voting periods.

The effort to make voting as accessible as possible has meant placing vote centers at locations including a tiny home village for people experiencing homelessness, a youth shelter, and a transitional housing site for women and children. Because the Flex Vote Center Program doesn’t only focus on unhoused voters, other locations included a jail and detention center, churches, city halls, and health centers, and other community organizations.

“I think that the combination of having Flex Vote Centers, same-day registration, all of these different things, makes it easier. It’s never going to be easy when you’re living in a tent, but easier for people to be able to vote when they’re unhoused,” said Kat Calvin, founder and executive director of Spread the Vote, which helps unhoused people and others obtain identification documents so they can vote. “I haven’t seen anywhere else in the country that’s worked as hard as they have in LA.”

The effort has had an effect: The Los Angeles County Registrar-Recorder/County Clerk’s office estimates that in the 2020 November General Election, a total of 2,794 people “who may not have had the opportunity to vote were able to accessibly, securely and independently cast their ballot in the General Election through the Flex program.”

At My Friend’s Place this year, at least 31 young people registered to vote, according to Mat Herman, a Safe Haven Counselor at My Friend’s Place. In the weeks leading up to the election, My Friend’s Place hosted voter education events on topics like the two major political parties, a primer on voting in local elections, and voting as a member of the BIPOC community.

“Overall, we really wanted to take this opportunity to educate [people] that just because you’re unhoused doesn’t mean you can’t vote,” said Herman.

That included letting people know they could vote without a permanent address, by listing the address of My Friend’s Place or using cross streets as their address. Across the U.S., no state requires voters to have a traditional residence to vote, although many potential unhoused voters are unaware of this, according to the National Coalition for the Homelessness. Lacking identification documents can also serve as a barrier in some states.

Even after registering, people experiencing homelessness still face barriers to voting. All but a dozen states and the District of Columbia have some form of voter ID laws, and roughly half require photo ID to vote. But frequent encampment sweeps makes obtaining proper documents more difficult. “We are constantly having to reorder birth certificates, re-get IDs, etcetera,” said Calvin.

And not having these documents can have cascading impacts, even in states like California without voter ID laws.

“If you don’t have an ID, you can’t get a job, you can’t get housing, you can’t get healthcare, you have bigger problems. And so it’s hard to even think about voting and participating in civic life when you don’t know where you’re sleeping tomorrow,” said Calvin.

Other barriers include overcoming historic and systemic disenfranchisement, as many established voting practices are based on the assumption that a voter has a permanent home address, from important voting information sent via mail to identification requirements in some states. In some ways, these barriers are the last remaining vestiges of the country’s first voting requirements, which only allowed white male landowners to vote.

Agabon estimates he personally persuaded over a dozen of his peers at My Friend’s Place to register to vote this year, in part by emphasizing the importance of weighing in on matters that directly how the election could impact housing and homelessness.

“A lot of people don’t know that if you vote for the wrong people, places like this could shut down,” said Agabon.

Measure A, the ballot initiative on the tax for homelessness services, ultimately passed with 58 percent of the vote. But other ballot measures focused on housing and homelessness didn’t fare as well. A statewide ballot measure aimed at making it easier for cities to expand rent control (which Agabon supported) failed for the third time in recent years. Still, it was important to Agabon and others that unhoused voters have a say in this policy that affects them directly.

“All the great programs we work with, they are all going to get help getting funded with Measure A,” said Herman. “We’re just trying to show them that this is a huge thing for your community, Measure A.”

The James Wood Community Center, where Barnett voted, was one of two voting locations for Skid Row residents this year. It operated as one of the county’s routine voting centers that opened the Saturday before the election, not a Flex VoteCenter.

It was an improvement on the 2020 general election, when there wasn’t a single official voting center in Skid Row. The only in-person voting option in the neighborhood was a mobile voting station that popped up only for election day, while other neighborhoods in downtown Los Angeles had voting centers open for four to 11 days.

For Barnett, the community center location was convenient—just a few blocks from the single-room occupancy hotel where he currently stays. He learned the vote center was open through “word of mouth.”

“We thought they forgot about us,” he said about the wait to find out if a vote center would open in Skid Row this year. “We’re aware of the issues. It was just that we didn’t know if they were gonna let us vote.”

As soon as Barnett heard the James Wood Community Center was open for voting, he made his way over, casting his ballot the first day it opened. “I was early,” he said.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.