New Progressive Bloc on LA Council Wants to Reshape How City Responds to Homelessness

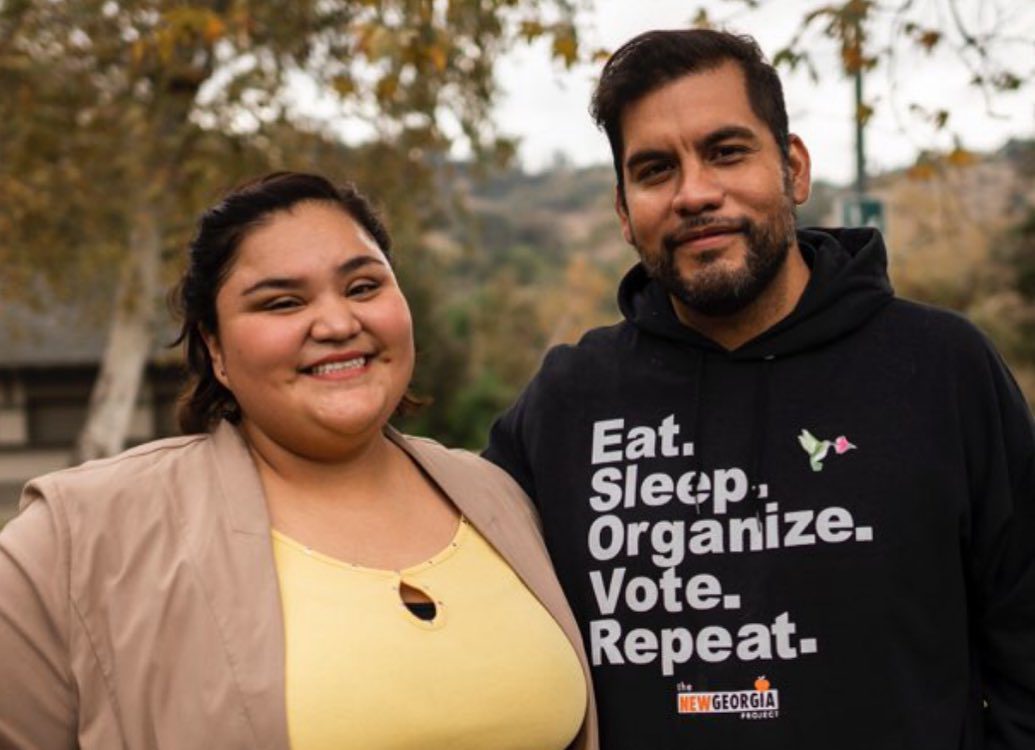

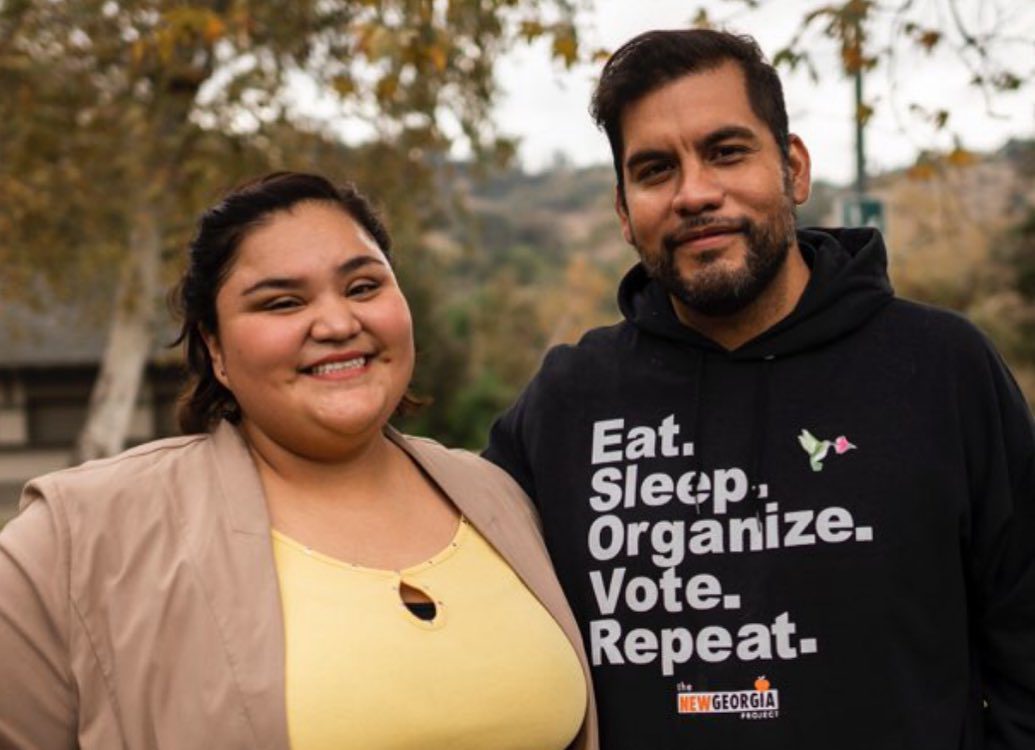

Fresh off election wins, Hugo Soto-Martinez and Eunisses Hernandez are joining forces with Nithya Raman to demand more care for unhoused residents and push against aggressive policing—first in their own districts, then throughout Los Angeles.

Piper French | December 16, 2022

On March 24, 2021, some 400 police descended on Echo Park Lake, a picturesque park near Downtown Los Angeles. They were there to clear, once and for all, a homeless encampment that had sprung up during the pandemic, on the orders of the district’s council member, Mitch O’Farrell, who had been trying to evict the residents for over a year. Service workers had provided outreach beforehand, but local activists denounced it as an insufficient pretext for the raid to come, and that morning a huge crowd gathered to oppose the actions of the police.

The result was pandemonium. Police helicopters hovered overhead long into the night. On the ground, LAPD surrounded and kettled protestors and journalists alike and commenced with mass arrests, including at least 16 members of the press; an officer broke one protestor’s arm with his baton. A year later, a UCLA report would confirm the protestors’ worst suspicions about the approach: vanishingly few of the unhoused residents of Echo Park Lake had been placed in long term housing, the whereabouts of many were unknown, and at least six people had died since being evicted from the encampment.

To Hugo Soto-Martinez, then a union organizer, Echo Park Lake evinced everything wrong with his representative’s approach to homelessness. “This was, without a doubt, the most egregious abuse of power that I’ve ever seen, exhibited by a council member to the most vulnerable community of our city,” he told Bolts. Soto-Martinez decided to challenge O’Farrell, casting the incumbent’s actions as a symbol of the cruelty and ineffectiveness of the city’s response to its ever-growing unhoused population. He won his election decisively last month, beating O’Farrell by 16 percentage points, and was sworn in as city council member on Sunday.

Soto-Martinez joins a new, three-member bloc of progressives on city council who vocally oppose criminalizing homelessness and support expanding tenant protections and deeply affordable housing. Nithya Raman, a former urban planner who joined the council two years ago, has been defending such an approach since then. And Eunisses Hernandez, an abolitionist organizer, won this year against sitting council member Gil Cedillo, who had deployed a similar strategy of encampment sweeps at his district’s MacArthur Park. Raman and Hernandez both supported Soto-Martinez’s campaign, and all three beat incumbents to secure their seat, a rare feat in LA politics; Raman’s win in 2020 marked the first time it had happened on the council in 17 years.

This week, in their first council session, Soto-Martinez and Hernandez quickly paired up to try to extend the city’s eviction moratorium. And Raman’s team is hopeful there will be strength in numbers going forward. “We’re hoping with some of these new friends in the city council, we can work with them to create a more citywide approach to the issue,” Josh Scarcella, Raman’s homelessness deputy, told Bolts.

These council members are coming to power in a city context that has been transformed by the election of Karen Bass as LA mayor and by the recent passage of Measure ULA, a high-value property sale tax that will fund tenant protections, affordable housing, and homelessness support to the tune of nearly a billion dollars per year. “This is a very unprecedented amount of funding that will enable the city to address the housing crisis at its roots—by both providing housing as well as preventing homelessness in the first place,” said Laura Raymond, the co-chair of the committee behind the measure. Its implementation will be overseen by a 15-person committee, and Raymond said that the coalition that fought for Measure ULA is recommending candidates like housing organizers, formerly homeless people, and tenants who have lived in affordable housing units.

Meanwhile, Bass, who had made housing affordability and humane solutions to homelessness a cornerstone of her campaign, declared a state of emergency on homelessness this week as her first official act as mayor, a move that allows the city to expedite affordable housing and homeless housing projects, among other things. She committed to getting 17,000 people off the street in her first year, saying the city would “make sure we are using every resource possible at the scale that is needed to save lives and restore our neighborhoods.” The progressive council members have expressed support for Bass’s approach, though some local organizers warn that it may put too much emphasis on speedy solutions rather than the long-term planning that may be needed.

With this sea change, Angelenos are facing an extraordinary opportunity to implement alternative models on housing and homelessness—and with that comes intense pressure to prove that their approach carries a better chance of getting more people off the street, humanely, than the city’s current methods of criminalizing homelessness.

Eric Ares, Hernandez’s incoming director of housing and homelessness, wants to undo what he sees as the prevailing framework by which people conceive of the city’s homelessness crisis. “There’s this false choice: either you accept the status quo, which is the tents as they are in our streets, or you criminalize,” he said. “The people that got voted on to join city council, many of them got voted on to explicitly explore the things that weren’t being addressed:Increasing tenant protections, building more housing intentionally at all affordability levels, especially for those who need it most, non-law enforcement crisis response.”

For much of the past two years, the city council’s work on homelessness has been consumed by fierce debate over the existence and expansion of anti-camping ordinance 41.18, which outlaws the presence of encampments near shelters, parks, schools, bridges, and other infrastructure. (An analysis by the recently elected left-leaning city controller, Kenneth Mejia, estimates it now stretches to include 20 percent of the city’s territory.) Only Raman and now-former councilmember Mike Bonin have consistently voted against 41.18. Council members can also propose individual 41.18 locations within their district, which must be approved by council.

In one meeting, Hernandez’s predecessor Cedillo successfully lobbied for 28 new enforcement zones in his district; meanwhile, Raman has never proposed a 41.18 zone in her district.

“In the past year, it’s a little bit of ‘every council district for themselves’ when it comes to homelessness,” said Scarcella. Within her district, Raman has established a homeless outreach team, including staff who work on legislation, liaise with service providers, and do direct outreach to encampments.

The council’s three left-leaning members met regularly in advance of the new session, which began December 13, and both Hernandez and Soto-Martinez are taking cues from Raman’s approach: hiring staff dedicated to homelessness and housing, establishing direct connections to homeless constituents and encampments, and expanding access to public restrooms, a stunning privation for most unhoused people in LA.

Both newcomers also denounced 41.18 on the campaign trail, and their offices told Bolts that they will not establish new 41.18 zones in their districts. “It just simply doesn’t work,” Soto-Martinez told Bolts. He also is advocating to stop using armed officers in encounters with unhoused people as a matter of course, and for the establishment of an unarmed response team, similar to Denver’s STAR program.

But both offices will have to quickly figure out how to respond to the daily displacement to which homeless people in LA are subject. During his campaign, Soto-Martinez promised to end the practice of comprehensive sanitation cleanings, often called “sweeps,” which regularly dislocate unhoused people, lead to the destruction of their belongings, and often involve police. But on December 13, Soto-Martinez’s first week in office, the mutual aid group LA Street Care noted on Twitter that the new council member had not acted to cancel a number of sweeps that were scheduled to take place in his district the following day, despite dangerously low temperatures. Within hours, Soto-Martinez’s office had downgraded the sweeps to a so-called “spot-cleaning,” according to LA Taco reporter Lexis-Olivier Ray, a designation that means that nobody is moved and that the LAPD is not involved.

Kris Rehl, an organizer with LA Street Care, went to all three sites, and was heartened to discover that the office had kept its word. “All three were just cleanings, what was reported,” Rehl said. “The fact that he was so responsive so quickly has made us really optimistic.”

Things get murkier when it comes to the 41.18 zones that Soto-Martinez and Hernandez’s predecessors have already established in the two districts. Scarcella said that the council office doesn’t control whether police enforce the anti-camping zones that exist in Raman’s district owing to the city-wide elements of the ordinance; the office is still trying to determine the best way to handle these situations. “Our goal is to work diligently with the individuals, provide outreach, and try to get them indoors,” he told Bolts, noting that LAPD is more likely to hold off on enforcement “if they see that there’s work being done, and there’s outreach being conducted.” Ares echoed that view. “The plan is to work with all the different partners that we have to ensure that whenever possible, we are leading with care and with services,” he said.

For all three council members, the end goal is to craft policy for the entire city based on the care-centered models they implement within their own districts.

The most critical element will likely be proving that they can get people off the streets and into housing.

Raman’s office has prioritized non-congregate housing like motel rooms, rather than shelter beds, in its efforts to get people into the pipeline to long term shelter. Her office was the only one to open a temporary housing site in 2021 called Project Roomkey, a former hotel with nearly 100 rooms, and residents were both allowed to stay as long as they needed and offered assistance on-site in seeking permanent housing. They have successfully rehoused 55 people through the site, which is temporarily closed pending a funding extension, are currently converting a recently purchased site for their permanent housing initiative, Homekey. “Her office has made tremendous improvements in connecting people with housing,” said Rehl.

Roomkey shut down in late 2022, which Soto-Martinez has criticized, calling it “LA’s most effective sheltering program” and arguing for it to be extended and improved. Bass wants to extend the program, which was federally funded.

Soto-Martinez also hopes to implement adaptive reuse (renovating existing infrastructure) as a quicker solution alongside building permanent housing—and eventually, social housing. He has his sights set on St. Vincent Medical Center, a massive, vacant hospital complex in his district. “We can refurbish these buildings much faster,” he told Bolts.

Hernandez told Bolts in February that she would fight to ensure that new developments in her district contained more units for low-income tenants. Ares spoke of the importance of having a joint strategy: speeding up the process of building new affordable housing while preserving the many existing affordable units in danger of expiring, using public land to build social housing, expanding access to temporary shelter, and keeping people in their homes in the first place. “We have to do all those things at once or else we’re not going to see the changes that everyone wants,” he said, invoking Measure ULA’s comprehensive approach to the city’s housing crisis. The measure devotes the bulk of its funds to affordable housing, including construction, adaptive reuse, and preservation, but also covers emergency rent relief and other tenant protections.

To make citywide changes, they will have to convince other council members of their approach.

Bonin, who was for some time the lone voice against criminalization on council, declined to seek reelection this year; the district’s new councilmember, Traci Park, is a firm supporter of 41.18, along with several colleagues. But there are a number of other council members who could side with the bloc on issues of housing and homelessness. And the balance of power could shift more fundamentally as well: in the wake of a leaked conversation filled with racist comments between three members of the LA city council and a union leader, Nury Martinez resigned as council president, leaving her seat up for grabs; Kevin de León, meanwhile, is desperately clinging to power amidst universal calls to resign and a recall attempt.

On the first day of the new session, that tenuous state of play was succinctly illustrated by Soto-Martinez’s first motion in council, which Hernandez co-presented, to remove the Jan. 31 end date from the ongoing pandemic emergency that has protected renters from eviction. They needed eight votes for it to pass, and three other council members joined with Raman to support the motion. With de León absent and Martinez’s seat lying vacant, though, they fell short by just two votes.

With the outgoing council having voted to end the city’s eviction moratorium on Jan. 31, thousands of tenants who are behind on their rent could lose their apartments. “We definitely know that the increase in homelessness in LA is very much directly tied to the need for expanded tenant protections,” Ares said. Raymound said Measure ULA will allocate enough money to fully fund access to a lawyer for tenants facing eviction; such counsel can greatly increase the chances of people being able to stay in their homes but is not currently mandated in LA the way the right to a public defender in criminal law cases is. Both Soto-Martinez and Ares told Bolts that their offices want to codify a right to counsel for tenants facing eviction this session.

Jacob Woocher, a tenant lawyer who organizes with the LA Tenants Union, says the council needs to go even farther to support tenants. He pointed to Raman’s touting of a universal just cause ordinance passed in October. “Just cause without rent increase protections—I don’t want to say it’s meaningless, but it’s much weaker,” he said. “If the landlord can’t get you out for any ‘just cause,’ what they can do is give you an $1,000 rent increase, wait 90 days for that to take effect, and then when that takes effect, and you can’t pay your rent—then you’re kind of screwed.”

Woocher said that he wanted to see the new city council members prioritize the needs of rent-burdened tenants and the homeless community over their relationships with their counterparts on council. “I just hope that they are willing to rely on the communities that put them in office and not be afraid to challenge their colleagues—and know that if they do go out on a limb, for tenants and for unhoused people, that the communities and organizations that have been organizing around these issues will have their back.”