How an ‘Ice Cream Truck’ for Voting Could Stop Pennsylvania Ballots from Being Tossed

This swing state rejects thousands of mail ballots a year over minor errors. A Montgomery County official wants to create a mobile unit for voters to cure their ballot where they live.

Alex Burness | February 7, 2024

Neil Makhija spent years promoting voter turnout in South Asian communities, and, as a professor of election law at the University of Pennsylvania, teaching new generations of attorneys about the fragility of the right to vote. But in 2020, he says, he felt frustrated watching the presidential race from the sidelines as then-President Donald Trump and his allies sought to invalidate lawful ballots and overturn election results with a barrage of failed lawsuits.

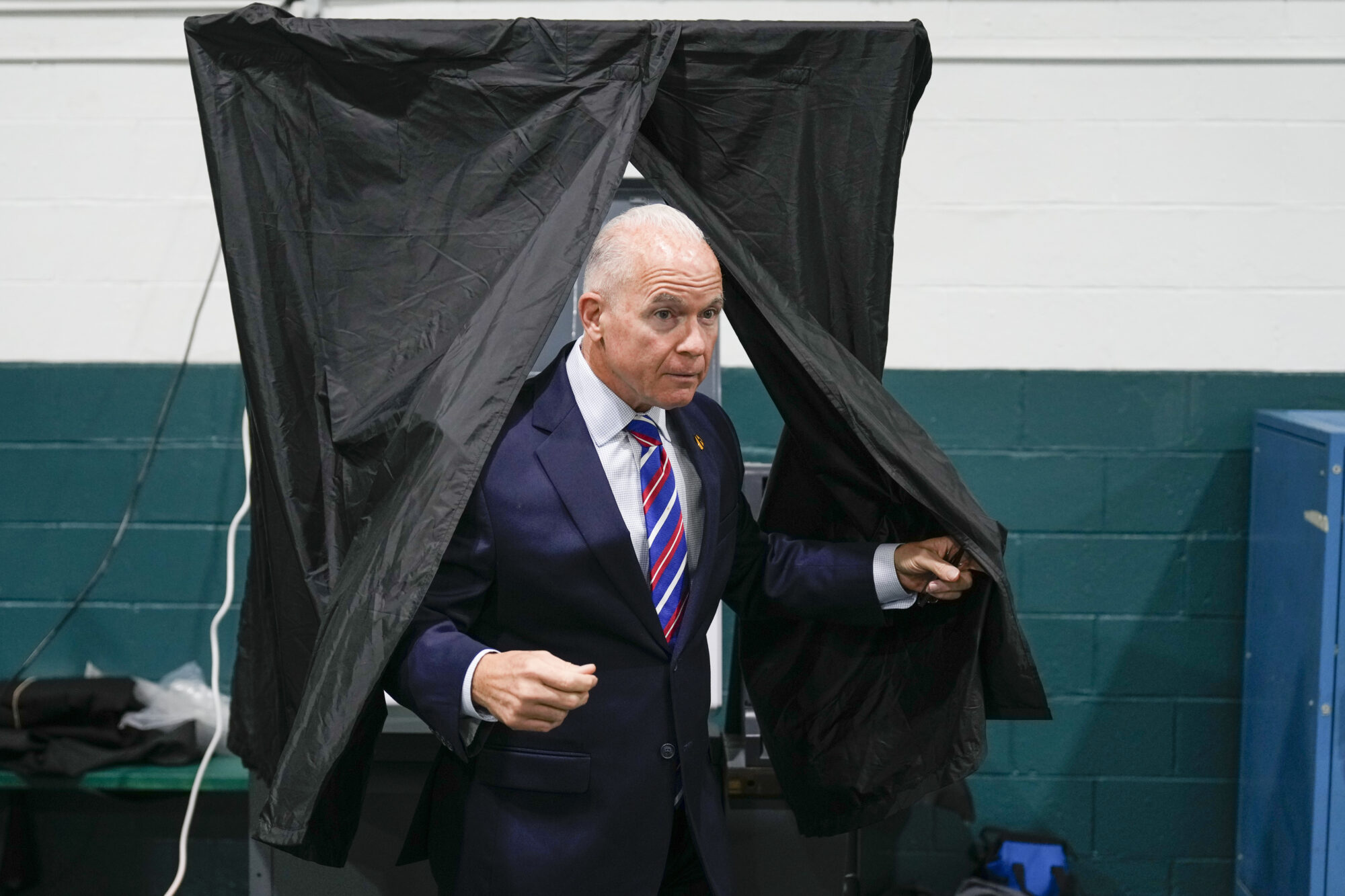

He decided to run for county commissioner in Montgomery County, a suburban area of 860,000 people northwest of Philadelphia. That board oversees more than half a billion dollars in annual spending across about 40 departments, but Makhija, a Democrat, says he was primarily motivated by one sliver of the body’s authority: setting rules for election administration.

Having won his election last November, Makhija is now in a position to secure voting rights from the inside. County commissions in most of Pennsylvania double as boards of elections, with broad discretion over election procedures, handing Makhija power to help shape how voting is conducted in the third most populous county of this pivotal swing state. And he’s intent on getting creative.

Makhija tells Bolts he intends to propose that Montgomery County set up a mobile unit that’d go into neighborhoods to help people resolve mistakes they’ve made on their mail ballots.

He likens his proposal, which election experts say does not currently exist anywhere in Pennsylvania, to an ice cream truck for voting.

“Imagine if voting was as efficient and accessible as getting an Amazon delivery or calling an Uber,” Makhija told Bolts. “Exercising fundamental rights shouldn’t be more burdensome.”

His idea is to strengthen Montgomery County’s process for ballot curing, the process by which voters get to resolve minor errors on mail ballots to ensure they are counted.

This is no abstract matter: Thousands of Pennsylvania mail ballots are tossed out every cycle due to any number of possible mistakes, including a missing or inaccurate date, a missing signature or one that doesn’t match the voter’s signature on file, or a so-called naked ballot returned with no secrecy envelope. These rejected ballots disproportionately come from older people and communities of color.

Pennsylvania provides no statewide guidelines for how local boards are supposed to handle mail ballots with errors. Some counties don’t allow voters to make any corrections to their ballots once they’ve been cast; others let them address a missing date or mismatched signature, but do little to notify them of the issue, much less to facilitate a fix.

Montgomery County is already more permissive than other parts of the state. Its elections office says it makes multiple attempts to contact anyone whose ballot is at risk of being rejected, offering them opportunities to come in and cure it, through phone calls, emails, and written letters. But even in Montgomery County the vast majority of mail ballots with mistakes are never counted. Francis Dean, the county’s director of elections, reports a roughly 10-percent cure rate; he says the county rejects at least 1,000 ballots every election cycle.

Makhija wants his county to do a lot more to stand out: He’s making the case that Montgomery County should meet people where they actually live, taking on more of the administrative burden of ensuring that mail ballots are cast correctly.

Under his proposed mobile program, county election workers would flag and set aside ballots that come in with mistakes. Then, over a roughly three-week period—the early-voting window leading up to Election Day—they’d bring those erroneous ballots directly to voters, who could cure them on the spot without having to make their way to an election office.

“The idea that a county official would know a ballot isn’t going to be counted, and sit on it for weeks—that, to me, feels like you’re depriving a voter of their right,” he told Bolts. “One of our obligations in government is to help people enforce their rights.”

Voting rights advocates in Pennsylvania say Makhija’s proposal would be a game-changer, even within the cohort of counties already making relatively strong efforts to prevent ballots from being tossed for technical errors.

“Ideally, we’d have that everywhere: very proactive election administrators doing everything they can to make sure people’s votes are counted,” said Philip Hensley-Robin, executive director of Common Cause Pennsylvania.

Makhija’s plan is an ambitious one, to be sure. The commissioner says he still has questions as to whether the county can unlock the resources to implement his vision. Dean, the elections director, who says he’s eager to work with Makhija on this, also says that it won’t be easy to reach hundreds of cure-eligible voters over a short period every election. Dean says he’s working to develop a cost estimate, and that even if the county is willing to pay for this project, it would also take a push to hire the workforce to carry it out. “Big ideas require an equally big commitment of resources,” he told Bolts.

Already this year, Makhija has led the way on another change that will ensure fewer ballots are rejected. The board of elections voted Jan. 23 to accept ballots even when voters have written the wrong year, or no year at all, on the envelope. (Voters who make that error won’t even have to fix, or “cure,” their mistake to be counted.)

The board’s decision codified part of a federal ruling in late November; following a legal fight, the judge ordered elections officials throughout Pennsylvania to count mail ballots on which voters either forgot to write the date or wrote the wrong date. That ruling is still working its way through the court system, now in the hands of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit.

Montgomery County, more than most, understands how important the November ruling was: it changed the outcome of that month’s election in Towamencin Township, where Kofi Osei, a Democrat, was running to unseat Republican Rich Marino on the board of supervisors.

Six Towamencin ballots with dating issues had been set aside before the court ruling, and those six broke five to one for Osei, erasing Marino’s four-vote lead and bringing the candidates to a tie. Per Pennsylvania’s bizarre rules to settle tied elections, Marino and Osei were each made to pick among a set of tiles numbered one through 30; the person who drew the lower number would win. Marino drew the number 28, and Osei drew 15.

Then, on Jan. 16 of this year, the county held a special election for a school district race. During the count, the county identified 75 voters who wrote no year on their ballot envelopes, or mistakenly wrote that the year was 2023; the Jan. 23 ordinance confirmed the county should count those ballots. The election was decided by more than 3,000 votes, so the 75 affected ballots didn’t determine the winner—but Osei’s earlier tiebreak victory reminds that 75 voters can be more than enough to tip a contest.

Adam Bonin, a Democratic elections attorney who represented Osei in the last election, laments that these policies are left to local governments to decide. Two voters who live on either side of a county border, who cast mail ballots with the very same curable discrepancy, may be offered vastly different opportunities to fix them based on the inclinations of their local leaders.

“It is incredibly unfortunate that we don’t have statewide standards on this,” Bonin told Bolts. “This isn’t about partisan results; this is about getting to every voter who is trying to vote, and giving them every chance for it to be lawful and get it counted.”

He added, “I would beg of the counties: What can you do to empower your voters?”

Democratic Governor Josh Shapiro’s administration late last year announced that the state would redesign its mail ballots with brighter colors and updated wording to minimize the possibility a voter makes a cure-worthy mistake. But with control of Pennsylvania state government split between Democrats and Republicans, advocates see little hope for a broader statewide fix this year to create uniform policy over the handling of ballots that are still erroneous. That means it will remain largely up to local politicians to set the tone in 2024.

This patchwork can prove confusing to residents, but also to voting rights groups that need to stay on top of a tremendous amount of fragmented information to know what they can do in one place versus another. “You don’t always know what you’re getting from county to county, and folks who are not actively paying attention and abreast of the situation especially may not know,” said Kyle Miller, Pennsylvania policy strategist for the national nonprofit Protect Democracy.

With exceptions, Democratic-run Pennsylvania counties have generally embraced more expansive rules on ballot curing, while GOP-run counties have tended to adopt more restrictive rules. Pennsylvania Republicans supported expanding mail voting five years ago, but mostly turned against it amid Trump’s false allegations of voter fraud.

Even Dauphin County (Harrisburg), which voted for President Biden by nine percentage points in 2020, has not offered ballot curing, as the idea was blocked by its then-GOP-controlled commission. The county flipped to Democrats in the fall of 2023 for the first time since at least the Civil War, and a new county commissioner told Bolts in November that he wants to advance reform this year. Democrats tend to also cast the majority of mail ballots in red-leaning places like York County that don’t enable curing, making them more vulnerable to having their ballots rejected.

But on the other end of the spectrum, counties that do allow ballot curing also differ vastly in how much they invest in making sure voters know about and can resolve ballot discrepancies.

At least six Pennsylvania counties have published public lists with the names of people whose ballots are at risk of being rejected, enabling third-party groups to step in to help inform voters, according to a survey by Votebeat. Montgomery County does not publish such a list preemptively, but it does share the names of anyone whose ballot has been rejected with campaigns that ask, Makhija said.

That approach still puts the responsibility of outreach on outside organizations, and it still asks voters to find time to come into the elections office. Makhija wants to go further. “We should not be putting the burden on our residents,” he said. “We should be making it as easy as possible.”

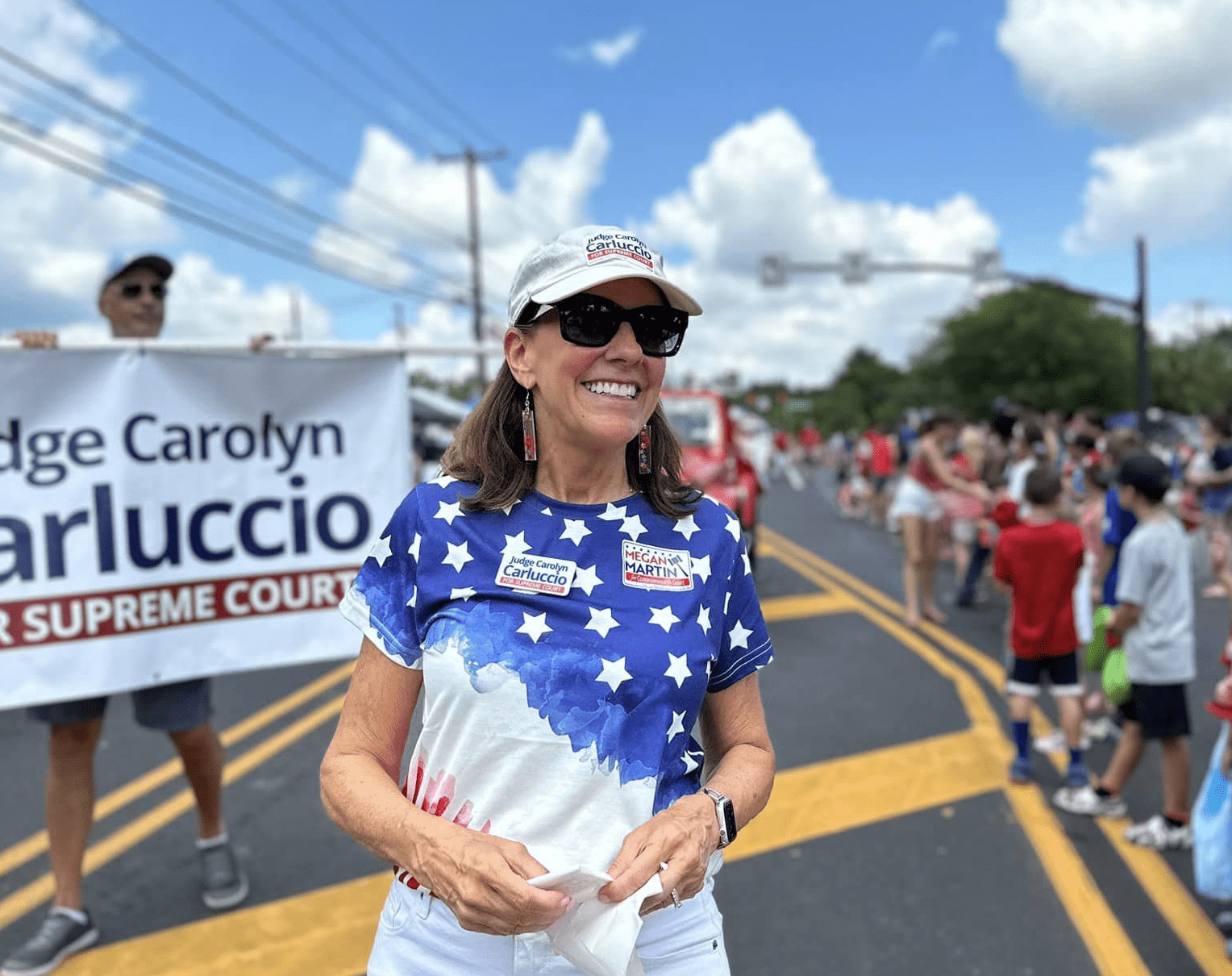

He expects to formalize his proposal for mobile curing “in the coming weeks.” The board of elections is made up of the county’s three commissioners, with Makhija chairing it alongside Democrat Jamila Winder and Republican Tom DiBello. Winder, who is generally his ally on expanding voter access, did not respond to Bolts’ interview request. Last month, she issued a statement criticizing the practice of rejecting ballots because of “a simple mistake that we all have made at one point in our lives.”

If the board approves the program, Makhija says the county likely wouldn’t be able to implement mobile curing in time for the April 23 primary, but that he wants to make it happen by November.

Dean pointed to less ambitious things the county could do in the meantime. For one, he plans to seek county approval to open four more offices at which voters could cure their ballots. At the moment, this service is offered at only one location in the entire county, forcing some far-flung residents to drive more than 40 minutes to correct a ballot issue.

He says he’s eager to think big and hopeful that Montgomery County can be an example for others in Pennsylvania. “I’m happy to be a part of a county that isn’t afraid to have those conversations,” he told Bolts. “The goal is to be setting the standard in Pennsylvania.”

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.