To Tackle Housing Crisis, These Organizers Want to First Change How City Hall Works

Advocates in Bozeman, Montana, are using a once-in-a-decade chance to reshape their local government structure to create more equitable representation and, eventually, more affordable housing policy.

| October 9, 2024

Joey Morrison, a city commissioner in Bozeman, Montana, and also the city’s next mayor, has lived in 13 different places since moving to town 10 years ago. He knows what it’s like to skip meals to save money, and he spent one summer living out of his car. At 29 years old, as far as anyone around here can recall, he’ll be the first Bozeman mayor who rents, not owns, their home.

His election victory last year was a landmark win for a burgeoning organizing movement known as Bozeman Tenants United, which emerged from protests in the summer of 2020, as thousands spilled into the streets of this lily-white, affluent, outdoor sports-obsessed college town, following the murder of George Floyd.

“Me and a few other organizers thought, OK, there’s a lot of energy—how do we get names and phone numbers and turn this into something that lasts?” Emily LaShelle, Tenants United’s organizing director, told me in July from the group’s church-basement headquarters.

Though protests provoked by police violence may not at first seem obvious venues for discussion of housing policy, LaShelle and colleagues found residents kept bringing up the city’s increasing unaffordability.

In conversations with neighbors during and after the protests, the organizers posed a simple question: What does public safety mean to you? “Was it having a third of the city budget being spent on the police force? Was it the military tank that Bozeman police has?” LaShelle said. “Time and time again, regardless of what people felt about the police, people said they couldn’t afford to live here, and that was making them less safe. It was resounding.”

Morrison, a co-founder of Tenants United, became an early test of the viability of this new progressive movement when he ran for the city commission in 2021 on a platform of economic justice. He lost by 24 percentage points. But then he ran again two years later, this time for mayor. In this city of roughly 60,000 residents, a campaign team of more than 100 volunteers knocked on some 15,000 doors, and Morrison wound up unseating a 13-year incumbent, nearly doubling her vote share.

Placing one of their own in the mayor’s office was a major step in the movement’s march toward a more equitable and accessible housing market in Bozeman, where about 60 percent of residents are renters. The Tenants United movement has been pushing policy to, among other things, restrict second-home vacation rentals, do less policing of homelessness, and set up publicly funded eviction legal defense.

This summer, the movement scored a significant win: Bozeman voters overwhelmingly approved the creation of a study commission to examine possible changes to the city’s local government structure.

Organizers with Tenants United worked hard to secure that result. Every ten years, the residents of all Montana cities and counties decide whether they want to revise their city charter, but this is the first time Bozeman has approved a review since 2004.

Morrison, LaShelle, and their growing corps of allies made the case this year that meaningful advances on affordability and economic justice require fundamentally rethinking how the city is governed: Currently, local leaders are paid around $20,000 for what can often amount to a full-time workload. This makes it too difficult, they said, for people who aren’t wealthy to hold city office. They want a study commission to advance structural reforms that would make Bozeman’s local institutions more inclusive of people who have been traditionally locked out of local politics.

And now that voters have set the study commission in motion, they’ll next decide in November exactly who will sit on the commission—and Tenants United has a few ideas for what the victors should do.

They want the study commission to consider reforming city government elections so that leaders are elected by districts—they are all currently elected at-large—which would upend a system that has, for at least thirty years, seen every single city commission seat won by a candidate who lived on the more upscale south side of Bozeman, according to a review conducted by Tenants United.

They want it to consider expanding the city commission from five members to seven or more, and then paying those members more money. They want it to consider stripping some power away from the office of the (unelected, but still massively influential) city manager and transfer it over to elected officials.

It’s a focus not just on individual laws, but on the conditions that determine how those laws get made. “We’re playing chess and checkers at the same time,” LaShelle says.

But no structural changes will be made if the study commission declines to recommend a reset. That makes the next step for these organizers quite important.

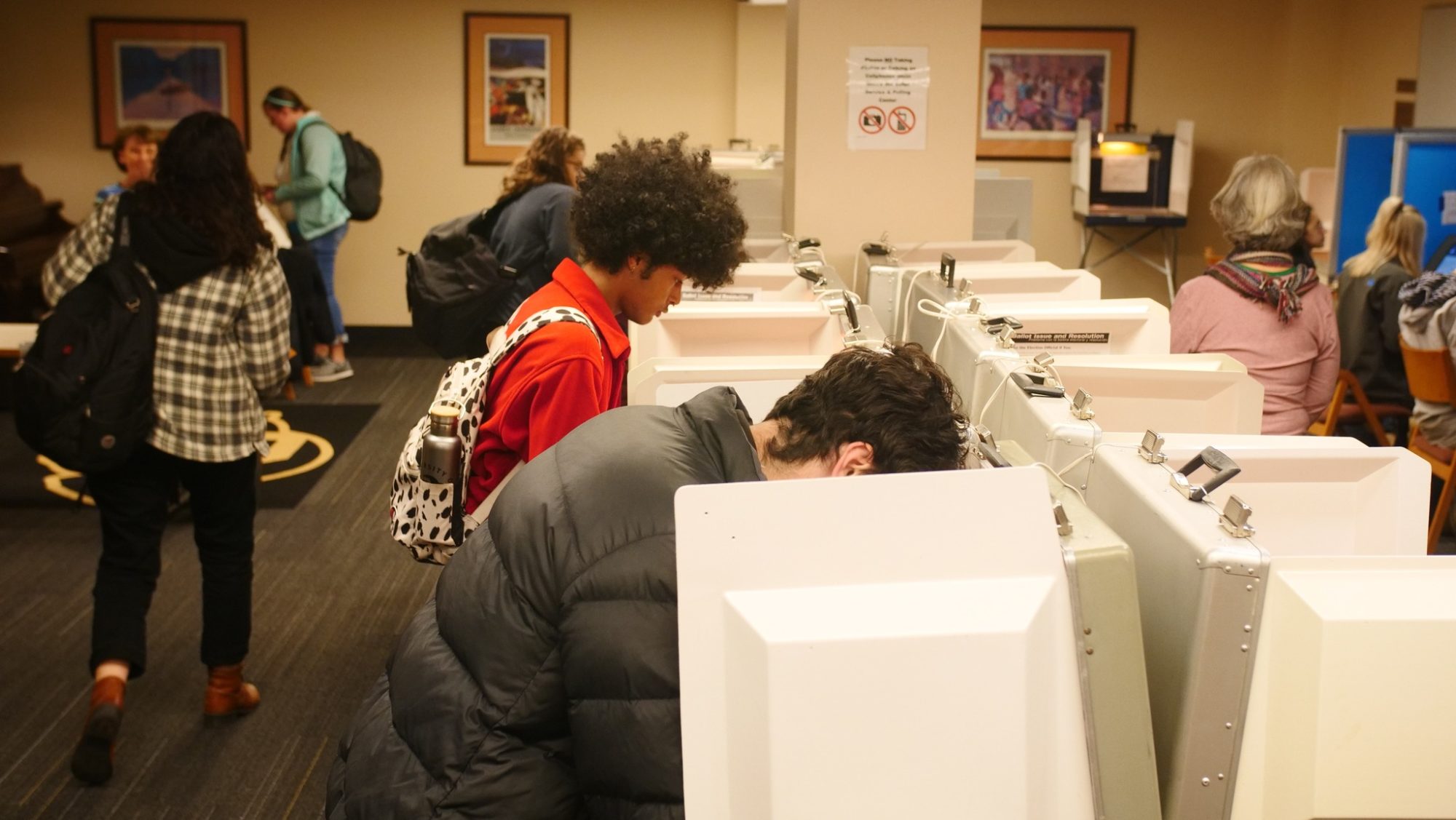

On Nov. 5, Bozeman will hold an election that is as down-ballot as down-ballot can be: voters will select five people, from a candidate pool of 15, to make up the actual members of this commission. These are the five people who will solicit input and eventually recommend changes to the city charter; any proposals would then have to be approved by voters in November of 2026.

Who gets elected in this obscure race will go a long way toward deciding if the study commission will have any appetite for the sort of fundamental reforms Tenants United is yearning for.

“It’s a weird little thing we’ve got going on down here, this process of electing our neighbors to determine our structure and function of government,” Morrison told me this summer, over coffee downtown. “It’s ironically the thing that is going to make the biggest difference to people in terms of material impact on our lives, but it is also going to be the thing that gets the least attention from voters.”

In a city where only about 30 percent of voters participated in the last mayoral election, it will be, and already is, a struggle to pique voter interest in a 15-way race for something so under-the-radar. But Tenants United sees opportunity. Like in other small cities, it is not necessarily money, but rather grassroots campaign tactics—yard signs, door-knocking, op-ed columns placed in the local paper—that can make all the difference in Bozeman elections.

“It’s so unsexy,” LaShelle tells me, almost cackling. “It’s gonna be really fun.”

It’s often said that states are laboratories of democracy, and this is arguably no more true anywhere than in Montana, because it’s the only state that regularly asks all its citizens to actively choose whether to amend, or even overhaul, their municipal and county government structures. The state constitution requires every municipality and county in the state to vote on a ballot measure, in the fourth year of every decade, to decide whether to undergo a review of their respective local governments.

These reviews, if approved by voters, do not concern granular policy questions, but rather structural ones: Should a city or county seize more local-control power, or rather align itself with what the state legislature commands? Is it better to elect a mayor with strong executive power, or to spread that power among other officials? How many people should serve on a local governing body, and should they be elected to represent districts or their entire jurisdictions?

“The reviews people vote on are basically generic calls to study how local government works,” Dan Clark, director of the Local Government Center at Montana State University, told me when we met just off-campus. “It’s a test of whether there is a sense of discontent within the community, or people feel there’s something that can be improved upon.”

There is, evidently, substantial discontent with local government in Bozeman, as the city grows in size and exclusivity. Its population has more than doubled since 2000, and the median new home price here is nearly $1 million. Many who love the city now are squinting to recognize it, and voters leapt at the opportunity to consider a local government review when it was on the June primary ballot; the measure passed 68 percent to 32 percent.

“It’s a gut feeling of betrayal, of losing home, when the favorite record store in town gets bought out and turned into a Lululemon,” says LaShelle, 26, who was raised here. “It’s a looming threat, constantly. I’m watching friends’ houses that used to be working-class set-ups of a bunch of younger folks living together getting turned into Airbnbs.”

LaShelle lives in a large, historic home near downtown with eight roommates. She pays $640 a month, the cheapest rent she knows of among her friends. The adjacent property was recently redeveloped into two units that each sold for $2.2 million. LaShelle thinks it’s a matter of time until something similar happens on her plot. “It feels very precarious,” she says.

Most of the rest of Montana is not so eager for structural change as Bozeman: 84 of the 127 municipalities that voted this year on whether to undergo local government reviews declined the offer. So, too, did 44 of 56 counties.

Passing the review measure does not itself change anything. It simply kicks off a process: The 43 municipalities and 12 counties that did approve reviews will each now elect their own study commissions in the fall. The commissions will draw up and then carry out community engagement programs intended to gather feedback. Those programs will likely comprise in-person events, online surveys, and perhaps other forms of outreach, though it will be up to each commission to decide its course. The commissions are tasked with using the feedback they gather to inform their decisions to place structural reforms on the ballot in 2026.

Most places never make any changes at all during the decadal review; in 2014, when this last happened, just four places, out of the 39 municipalities and 11 counties that had approved reviews, ended up passing something on the 2016 ballot, according to Clark.

It’s a long game, then, for Tenants United and anyone else hoping to use this vote to catalyze policy change.

Clark, who is widely seen as the state’s preeminent expert on this review process, said that the stage Montana is in now—the study commission elections—has never been a headline-maker. He’s not aware, he told me, of a single candidate for a study commission anywhere in Montana who has raised money to run a serious campaign.

“In many cases, in the smaller communities, no one files to run at all, and they have to find people by pulling teeth,” said Clark, who, before moving to Bozeman, was once the mayor of the small Montana town of Choteau.

He said he’s rarely seen as much interest in a study commission as has popped up this year in Bozeman, where there are three times the number of candidates as the number of available seats. There’s massive interest, too, in Gallatin County, where Bozeman is located, which also approved a review in June and now has 22 people vying for its commission.

These study commission elections, which are nonpartisan, have usually not been very heated, Clark tells me, because candidates have traditionally sought to position themselves as mere facilitators of community debate, as opposed to political actors.

That is not the dynamic in Bozeman this year, however. With fifteen candidates running for five slots under one ballot heading, the county Republican Party has endorsed five people: Roger Blank, Deanna Campbell, Emily Daniels, Harrison Howarth, Stephanie Spencer. Tenants United has endorsed a competing slate of four: Carson Taylor, Rio Roland, Jan Strout, and Barrett McQuesten. Six more candidates are running without endorsements from either of these wings.

There is a good chance that Bozeman’s study commission will be open to considering structural reforms no matter who is elected. A recent forum hosted by Tenants United, in which 10 of 15 candidates participated, revealed that most attendees—including some backed by Republicans—support increasing pay for city leaders and expanding the number of seats in city government.

Morrison said he’s relieved that Tenants United has no organized opposition in this election from the home-owning liberals who have long controlled City Hall. He said he’s more worried that Republican-endorsed candidates will win seats and fail to center class justice once seated on the study commission.

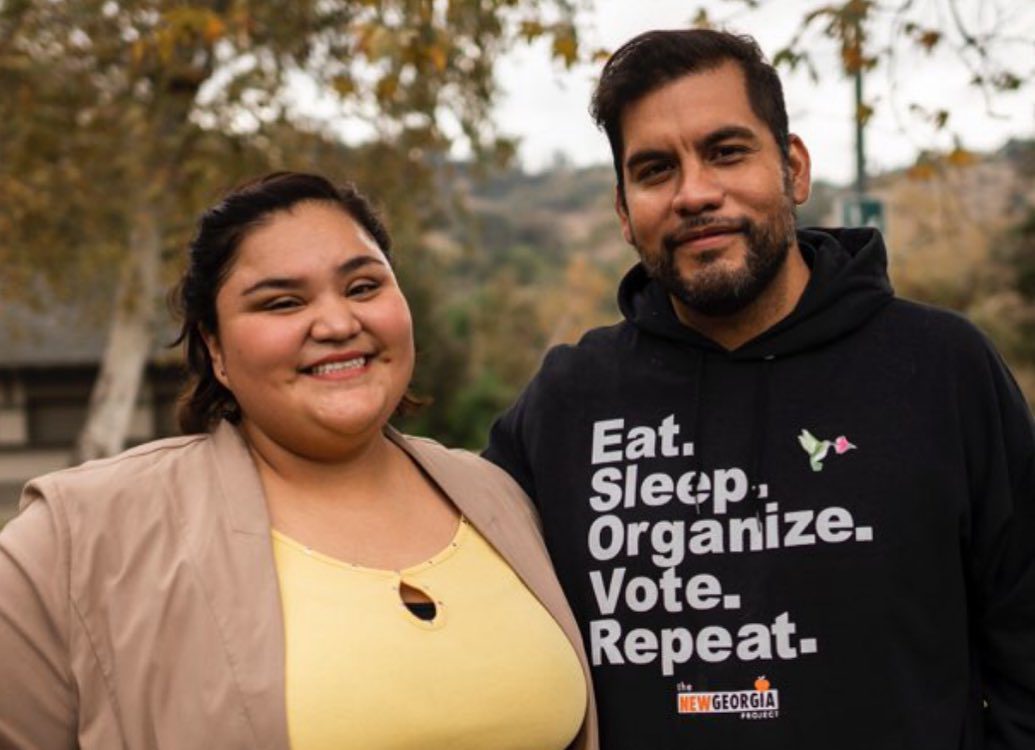

McQuesten, one of the study commission candidates, who is also an organizer with Tenants United, said that he wants a study commission that urgently feels Bozeman government should be more diverse. He said he’s running not to be a fly on the wall for community conversations about representation in government, but to help advance specific reforms to the 2026 ballot. He supports expanding the city commission and electing members by district instead of at-large.

It’s not that he won’t be an open-minded listener if he wins in November, he said, but rather that he’s seen too much in his 11 years in Bozeman to have his mind changed, on certain issues.

McQuesten, a 29-year-old paraprofessional educator, told Bolts, “I saw really, really solid educators who weren’t making enough to be able to live here. When I managed a McDonald’s, I had employees forced into homelessness because their rent went up. It’s kind of heartbreaking.”

He adds, “I want to be empirical where I can be, but there are some things that haven’t been working that need to be changed.”

Morrison says he regards the proposal to elect city commissioners in districts as most important because it will necessarily disrupt the long-term power center of Bozeman’s wealthier south side.

“It forces the opportunity of representation,” he says. “We need easier access to more diverse representation across our city, which will consequently mean differences in class, age, experience.”

He notes, correctly, that people all across the city are already free to run for the city commission. But he says there are at least a couple of big reasons why homeowners from the same part of town almost always win: For one, working-class people usually can’t afford to even consider seeking the job. But, perhaps more importantly, the south side holds on to power because those voters actually turn out to vote in municipal elections.

A basic rule of municipal elections in Bozeman, former Mayor Carson Taylor told me, has been that people on the south side tend to vote “regularly,” that people in the northeast vote “less often,” and that people on the west side, which is home to most of the city’s recent growth, “tend not to vote very much.”

I met with Taylor, who is 78 and now running for the study commission, at a cafe on the south side of town. He’s retired, he owns a home that he’s been told would sell for about $1.5 million, and he has lived in the city long enough to be on a first-name basis with all of its power players. He says he endorses the changes Morrison and allies seek, including the move to by-district municipal elections.

Bozeman, Taylor told me, cannot continue operating as it has, with so many of the people who live here worrying about housing stability, falling homeless, or just moving out of the city entirely.

“If you leave it to chance, we’re screwed, in my humble opinion,” he said. “You have houses that are built for people that have a lot of money, you have less affordability, and the worry is that we’re going down that road and we’re not getting off of it fast enough.”

Taylor hopes structural reforms in Bozeman will not only produce more diverse representation, but also inspire a more diverse electorate. He and others believe that it would make a big difference if people from all over town knew they had a neighbor at City Hall.

“When you knock doors,” LaShelle said, “you’ll talk to folks on the south side who know the former mayors. You go to the northwest side of town and people say, ‘No one in this city gives a fuck about me.’ They’ll tell you that no one tells them anything about when a new development is coming in, or when an intersection is changing.”

Everyone from Clark to Morrison to Taylor seems to agree that electing city commissioners in districts does not itself promise any course correction. Plenty of other places with housing affordability crises elect city leaders this way, and most of Montana’s biggest cities, including Great Falls, Billings, Helena, and Missoula, already do, too.

That’s why Tenants United doesn’t see this November’s election as a final step, just as it did not allow itself too much satisfaction with Morrison’s mayoral win.

After all, what good is an overhauled government structure to this movement if it can’t produce policy change that prioritizes housing affordability?

But there is a key difference, LaShelle believes, between Bozeman and other cities in Montana, and beyond, that have adopted some of the reforms that the study commission could consider. “An underlying issue in all these places is that working-class people have not been organized,” LaShelle said. “And here, they are getting organized.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.