New Jersey Prisons Isolate Trans Women Even After Reforms to Reduce Solitary Confinement

The treatment of trans women inside New Jersey prisons highlights the limits of a landmark law the state passed in 2019.

Adam M. Rhodes | December 1, 2023

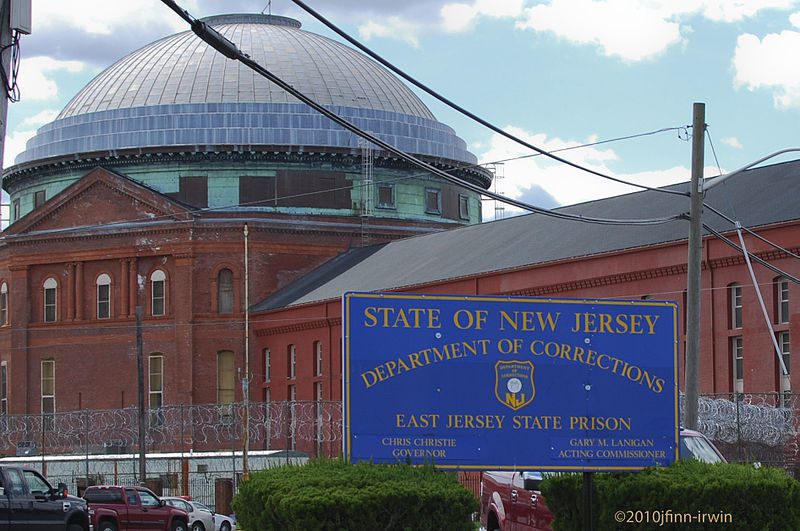

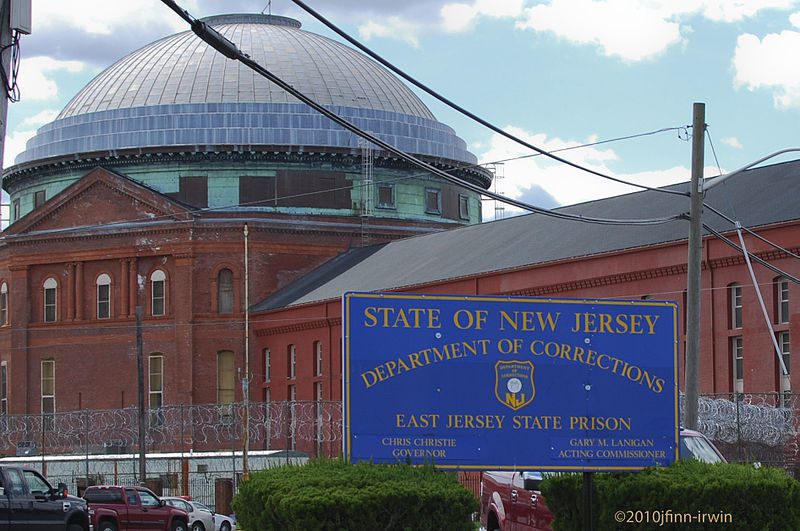

Jamie Kim Belladonna, a trans woman incarcerated inside New Jersey State Prison in Trenton, lives in intense isolation. She says she has little to no interaction with anyone besides guards and other prison staff, spending almost the entirety of each day inside a cramped cell where a bed frame and storage boxes take up most of the floor space. She mostly only leaves her cell to shower and to use an electronic kiosk for her allotted 20 minutes to send emails and make calls.

Belladonna lives in protective custody inside a men’s prison, a housing assignment for people at higher risk of victimization that separates her from the rest of the prison population. She calls the isolation excruciating. “[Protective custody] is so locked down that the world doesn’t know it’s actually a form of solitary confinement,” she told Bolts by email. She said the prison does little to help her deal with the devastating mental health effects of the isolation. When she does get recreation time, she says she spends it in tiny one-person enclosures that she says are known as “dog cages.”

Trans women in New Jersey prisons say they are routinely isolated for all but one or two hours a day, despite recent reforms to reduce solitary confinement in the state. Gia Abigaill Valentina, another trans woman inside NJSP, said she’s usually locked in her cell for almost the entire day and similarly is given little help coping with the near total isolation. “There is no programming for the transgender women here. The only counseling provided is routine mental health services, in which someone from mental health comes around every two weeks,” Valentina said in an email from the prison. “In this lock down unit I am made to stay in my cell for 23 hours a day. I am allowed out for kiosk and shower.”

The isolation that trans women endure inside New Jersey prisons demonstrates the limits of a landmark reform law that state lawmakers passed in 2019 to reduce solitary confinement. The law, the Isolated Confinement Restriction Act, hailed as the most progressive solitary reform at the time, put strict limits on “isolated confinement”, which it defined as holding someone in a cell for 20 or more hours each day with “severely restricted activity, movement and social interaction.” The law also prohibited isolation of vulnerable groups, including LGBTQ+ people, but still left corrections officials with broad discretion over when to use isolation, including for protective custody. While the law spells out specific guidelines related to vulnerable populations like pregnant or disabled prisoners or those under 21 and over 65 years old, there are none regarding those who are or perceived to be LGBTQ+.

When prison officials do use isolation, the law says it cannot go longer than 20 consecutive days or 30 days in a 60-day period. But Belladonna says she has been isolated since early February—roughly ten months, as of the date of publishing.

Isolation of trans women in protective custody is just one of the ways solitary conditions persist in the New Jersey prison system despite the reforms. A recent investigation by HuffPost and the Inside/Out Journalism Project found that more than three years after the 2019 law was passed, the prison system’s main alternative to isolated confinement—so-called Restorative Housing Units (RHUs), where incarcerated people are isolated as punishment for breaking prison rules—is largely solitary by another name and seems to defy the reforms. Days after that investigation was published, in early October, New Jersey’s Office of the Corrections Ombudsman, a state prison watchdog, published a report echoing those findings.

“We found that on any given day, 700+ people are confined to a prison cell for 22-23 hours per day,” Terry Schuster, the New Jersey Corrections Ombudsperson, said in an email. “People spend months or years in these disciplinary tiers, called Restorative Housing Units (RHUs), and reached out to our office in large numbers to draw attention to the apparent violations of state law.” The office confirmed to Bolts that it has also received reports from transgender people about the extent of their isolation.

A spokesperson for the New Jersey Department of Corrections (NJDOC) did not respond to questions for this story, including how many transgender people are in isolation conditions inside the state’s prison system.

Research has consistently shown that solitary confinement has disastrous consequences on mental and physical health. According to psychiatric experts, isolation can both exacerbate existing mental health issues and even cause the onset of mental illness. And according to a recent study, time in isolation can also increase someone’s risk of death in the first year after release from incarceration, namely from suicide, homicide and opioid overdose.

There is also overwhelming research to indicate that LGBTQ+ people face egregious and disproportionate violence behind bars. More than half of respondents to a 2022 national survey by legal advocacy group Lambda Legal and prison abolitionist organization Black & Pink said they had been sexually harassed by jail or prison staff, while 1 in 6 said they had been sexually assaulted. A stunning 87 percent reported verbal assault.

Alongside this pervasive abuse, trans people in prison often land in isolation. A recent report in The Nation detailed how trans people disproportionately face isolation in federal lockups, citing data from the Federal Bureau of Prisons from 2017 to 2022 that showed incarcerated trans people are typically two to three times more likely to be put in “restrictive housing” than cisgender people.

Valentina said she landed in isolation at NJSP after being transferred from the state’s only women’s prison, the Edna Mahan Correctional Facility, earlier this year after Governor Phil Murphy announced his plans to shutter it following years of scandals there. Her path out of isolation isn’t as simple as moving to a women’s prison, particularly in light of a policy NJDOC quietly enacted late last year that gives prison officials greater leeway to override trangender prisoners’ housing preferences. Under the new policy, prisoners have a “rebuttable presumption” that they are housed according to their wishes, but officials now can override that preference based on factors including “reproductive considerations.”

The new policy was enacted months after another trans woman, Demi Grace-Minor, impregnated two women at Edna Mahan during what NJDOC officials said were consensual sexual relationships. A resulting media firestorm and transphobic criticism preceded the policy change, which now bars many trans women from easily obtaining housing that experts say could make them safer while behind bars.

The new housing policy could also put the New Jersey prison system at odds with the federal Prison Rape Elimination Act, which tasks prison officials with giving serious weight to a trans person’s housing preferences; still, recent reporting shows that trans women are almost always housed in men’s facilities. PREA also requires housing to be decided on a case-by-case basis, which Valentina said isn’t happening for trans women in New Jersey prisons.

Valentina alleges that under the new policy, prison officials won’t send trans women to women’s units until they get bottom surgery—referring to surgeries that often include an orchiectomy and vaginoplasty—to eliminate any “reproductive considerations.” Valentina, Belladonna, and other trans women have repeatedly said that they face agonizing, oftentimes bureaucratic, delays in actually obtaining these surgeries, leaving them trapped not just in men’s prisons but in continued isolation. Trans women in New Jersey prisons also allege that medical and mental health care are grossly lacking.

“I truly suffer every second of every day with not having my full surgery, although I feel so much better since my first gender affirming surgery,” Belladonna said.

“I can honestly express with truth and sincerity that I have NEVER in my life encountered or felt such discrimination, hatred and transphobic opposition as I have experienced since coming out here in the NJDOC,” Valentina said.

Some trans people have been pushed to extremes to alleviate their suffering. Belladonna has thrice mutilated herself, including trying to cut off her penis, and recently tried to remove her testicles, in order to relieve herself of the debilitating dysphoria she faces without gender affirming procedures.

Belladonna said that even if she were to be offered less restrictive housing, she would still have to turn it down out of concern for her own safety—meaning she will likely stay isolated until she can move to a women’s prison.

“I signed into protective custody because in a man’s prison PC is the safest place versus the prison’s ‘male population’ for someone as advanced in her transition as me,” she said.

Like Belladonna, Valentina also detailed efforts to remove her penis herself amid delays in obtaining gender affirming care and a lack of adequate mental health care.

And when weeks after Grace-Minor was sent back to Garden State Youth Correctional Facility after the pregnancies at Edna Mahan, she similarly tried to remove her testicles. At the time of the incident, Grace-Minor was housed in isolation and said she felt unsafe surrounded by men. Grace-Minor is now incarcerated in Northern State Prison in Newark.

“It has been pure hell back here in solitary: lack of food, being sexually harassed and housed around men who flash their genitals and refer to me as ‘he-she bitch,’” Grace-Minor wrote on a public blog in September 2022. “I doubt that I will survive all of this.”

Surgeries aside, trans women in New Jersey prisons say they’ve also had to fight for months to get basic necessities like hair ties, proper underwear and even deodorant. Their complaints mirror allegations from a lawsuit filed against NJDOC in 2019. The plaintiff in that lawsuit alleged that corrections officers misgendered her, denied her female commissary items and failed to prevent harassment against her, all of which trans women say still happens in New Jersey prisons.

That lawsuit, brought by the ACLU of New Jersey on behalf of an anonymous trans woman, ended with a settlement in June 2021 and a change in NJDOC’s housing policy to give trans prisoners a “presumption” that they would be housed in line with their gender identities, a policy it had to maintain for at least a year. Four months after that time period lapsed, NJDOC rolled back the policy to give prison officials greater discretion over housing assignments for trans people.

Amid the constellation of struggles these women face behind bars, they agree that moving to a women’s prison would make them feel safer, but that likely won’t happen until they obtain bottom surgery, which all of them are desperately waiting for. And until then, their isolation and the anguish that comes with it—compounded by their continuing dysphoria absent gender-affirming surgery—will continue.

Belladonna called her situation “agonizing,” writing in a recent email, “It is torture for me because I only have half of my bottom surgery and so I’m stuck in the room all day with this part that doesn’t belong to me.”