“It Just Feels Like Death”: Barrage of New Rules Target Arkansas Ballot Initiatives

Faced with popular initiatives to protect abortion rights and other measures they dislike, state Republicans are passing new bills that local advocates say will hollow out direct democracy.

| March 10, 2025

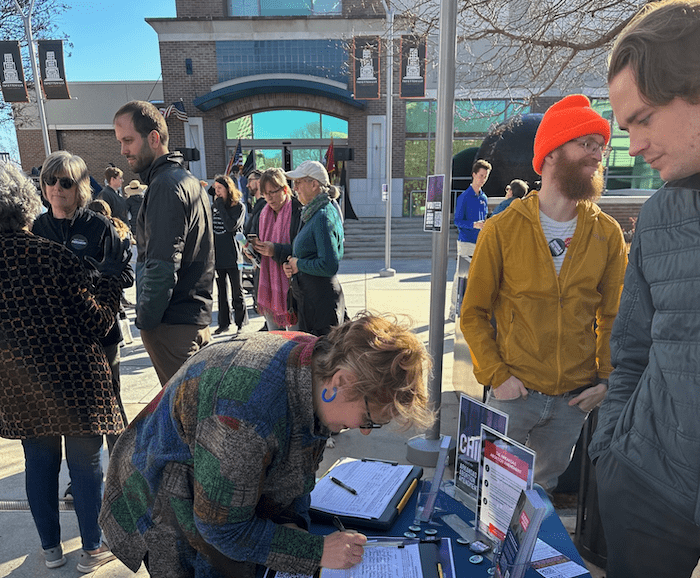

It’s a familiar sight in Arkansas: Canvassers stop passersby in front of a local grocery store or town library and ask them if they’d be willing to sign a petition to put an initiative on the ballot. In 2024, though, citizen efforts to expand medical marijuana, enable abortion access, and protect education funding all fumbled when GOP officials declared that organizers had messed up some regulatory minutiae. They said the abortion rights organizers erred in how they submitted certain documents, failing to bundle them together with their final petition, and that the medical marijuana organizers had the wrong person sign some of their paperwork. In each case, officials disqualified thousands of signatures and kicked the measures off the ballot.

Organizers in Arkansas already face this mountain of technical rules to satisfy—down to the color of the ink that notaries public must use on petitions. But now, the state is about to make this obstacle course even tougher.

The GOP-run legislature this spring is advancing at least six bills containing a barrage of additional rules that canvassers will need to follow. The new rules give state officials even more excuses to toss initiatives, and they explicitly strengthen the attorney general and secretary of state‘s powers to stall or block proposals. Arkansans with experience collecting signatures also worry that the increased threat of criminal penalties may intimidate citizens from canvassing and signing in the first place.

Melissa Fults, who helped lead last year’s effort to expand medical marijuana, says the bills are intended to grind initiatives like hers into the ground. “They’ll have every loophole within their means to kick it off the ballot, and that is their sole purpose,” she told Bolts.

Most of these changes were authored by Republican Senator Kim Hammer, who announced in January that he is running to become the next secretary of state. Hammer filed his bills weeks after announcing his candidacy. Should he win the office, they’d give him vast authority over future ballot measures. Fults warns that his bills are poised to transform the secretary of state into “judge, jury and executioner for the petitioning process.” Hammer did not respond to requests for comment.

As it stands, the new powers established by this package would go to Secretary of State Cole Jester, a Republican who was appointed to the office in January and who will oversee any initiative drives heading into the 2026 midterms. Jester’s office told Bolts that he supports Hammer’s package. “The Secretary supports any legislation that promotes election integrity, including integrity in the petition process,” said Samantha Boyd, a spokesperson for his office. Boyd said the state supreme court will still be able to review decisions made by the secretary of state.

Under Hammer’s new bills, prospective petitioners would need to show a photo ID to a canvasser; they’d have to read the initiative in full during that interaction, or have the canvasser read it to them outloud. Canvassers would also have to tell each person who is interested in signing a petition that they’re liable to face criminal charges if they commit fraud, and then when turning in signatures have to submit a new affidavit certifying that they’ve followed all these rules on top of all the documentation that’s already required. Canvassers could face criminal charges for failing to observe some of these regulations.

Hammer’s package also grants the secretary of state’s office authority to disqualify signatures if it deems that there is a “preponderance of evidence” that these rules have been violated. A separate bill, authored by Republican Representative David Ray, gives the attorney general new reasons to reject an initiative before canvassing even starts; the office will now review an initiative’s language and decide whether it violates the U.S. Constitution or federal statutes.

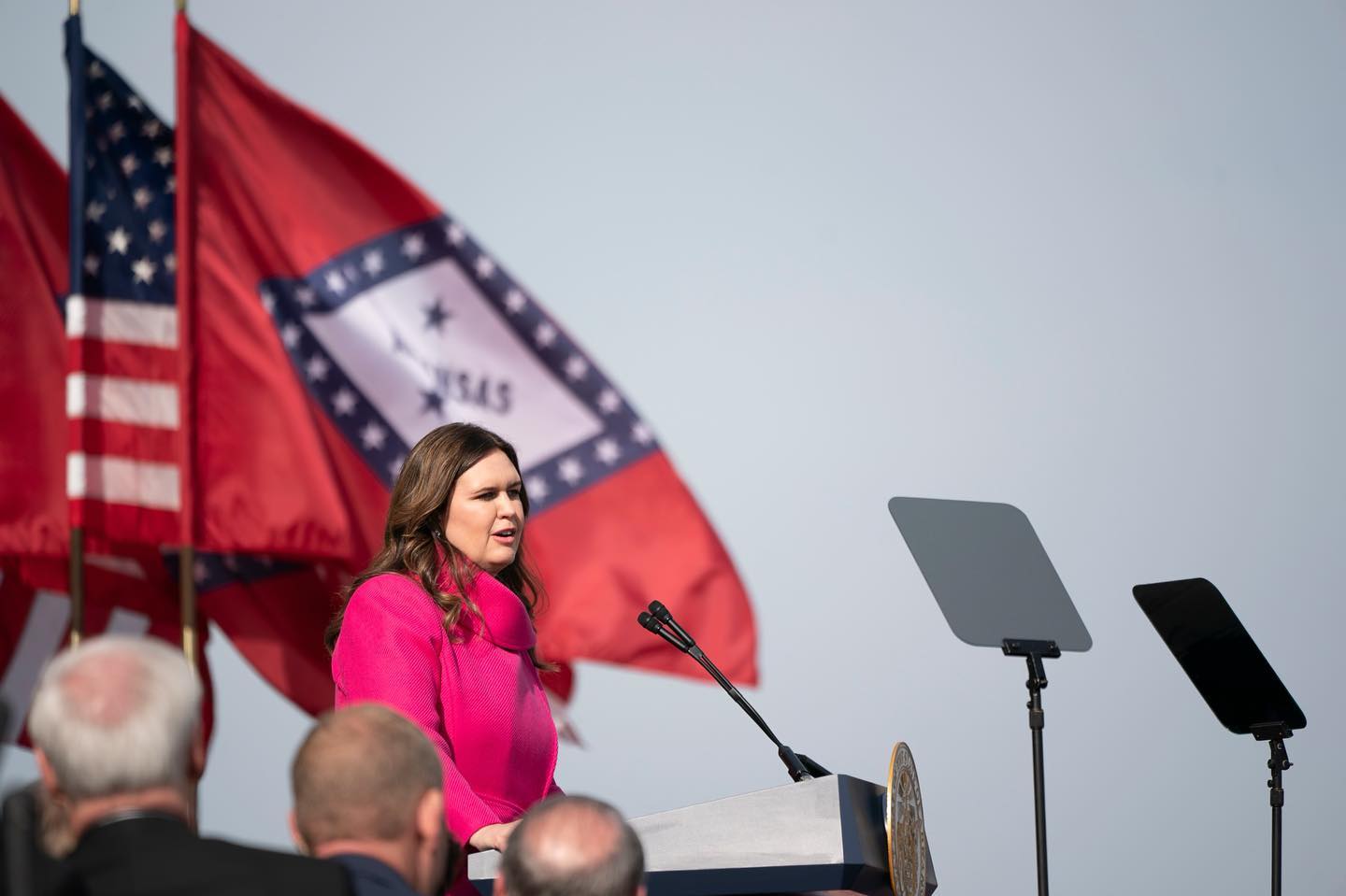

Of the six bills that Bolts is tracking this session, four have passed the legislature and have been signed into law by Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders. The remaining two, SB 209 and SB 210, passed the Senate in February and are moving through the House. The bills have advanced thanks to Republican support in a legislature where they outnumber Democrats four to one, though a dozen Republican lawmakers across the two chambers joined Democrats in voting against some of them.

“Even just one of these alone would be so detrimental to the rights of voters,” says Bonnie Miller, president of the League of Women Voters of Arkansas. “When we’re looking at these as a whole, it just feels like death to the initiative process in our state.”

Like other Arkansans who talked to Bolts for this article, Miller focused her criticism on the proposed requirement that petitioners read a proposal in its entirety or have it read to them by the canvasser. Under current law, canvassers already show prospective signers the text of the measure. Requiring a full reading would balloon the interaction time since measures tend to be very lengthy and full of legalese. In testing the rule, it took this reporter nearly four minutes to silently read last year’s marijuana initiative; it took nearly six minutes to read it outloud.

“It’s quite ridiculous, I cannot even logistically imagine doing it,” said Miller. “It’s already so difficult to collect signatures. When you’re out there in the heat, in the cold, you’re talking to people—it’s all you can do to be able to get a few moments of their time to explain the measure.”

“We are to require folks to stand outside for ten minutes to read a ballot title? We don’t even have these requirements to sign a candidate’s petition,” she said.

Miller is nervous about the fact that Arkansans will now be making decisions about whether to volunteer for an initiative under the fear of criminal penalties. She worries that state officials may turn technical errors into full-blown police investigations. “What if the potential signer appeared to merely skim through the language?” Miller asked. “Are you supposed to question them? If you don’t and someone is watching/recording then you’re on the hook for a crime.”

With the new bills, she said, prospective canvassers will “be afraid to even engage in this work.” Other advocates told Bolts that passersby will be similarly scared off from signing petitions once they’re told by canvassers that there’s any risk of criminal charges.

In Florida last year, Governor Ron DeSantis deployed a state police force to question citizens who had signed an abortion rights measure. Other GOP-run states have passed laws in recent years that criminalize some aspects of the elections process, from registration drives to voter assistance. Some third-party groups have chosen to dial down their activities in response.

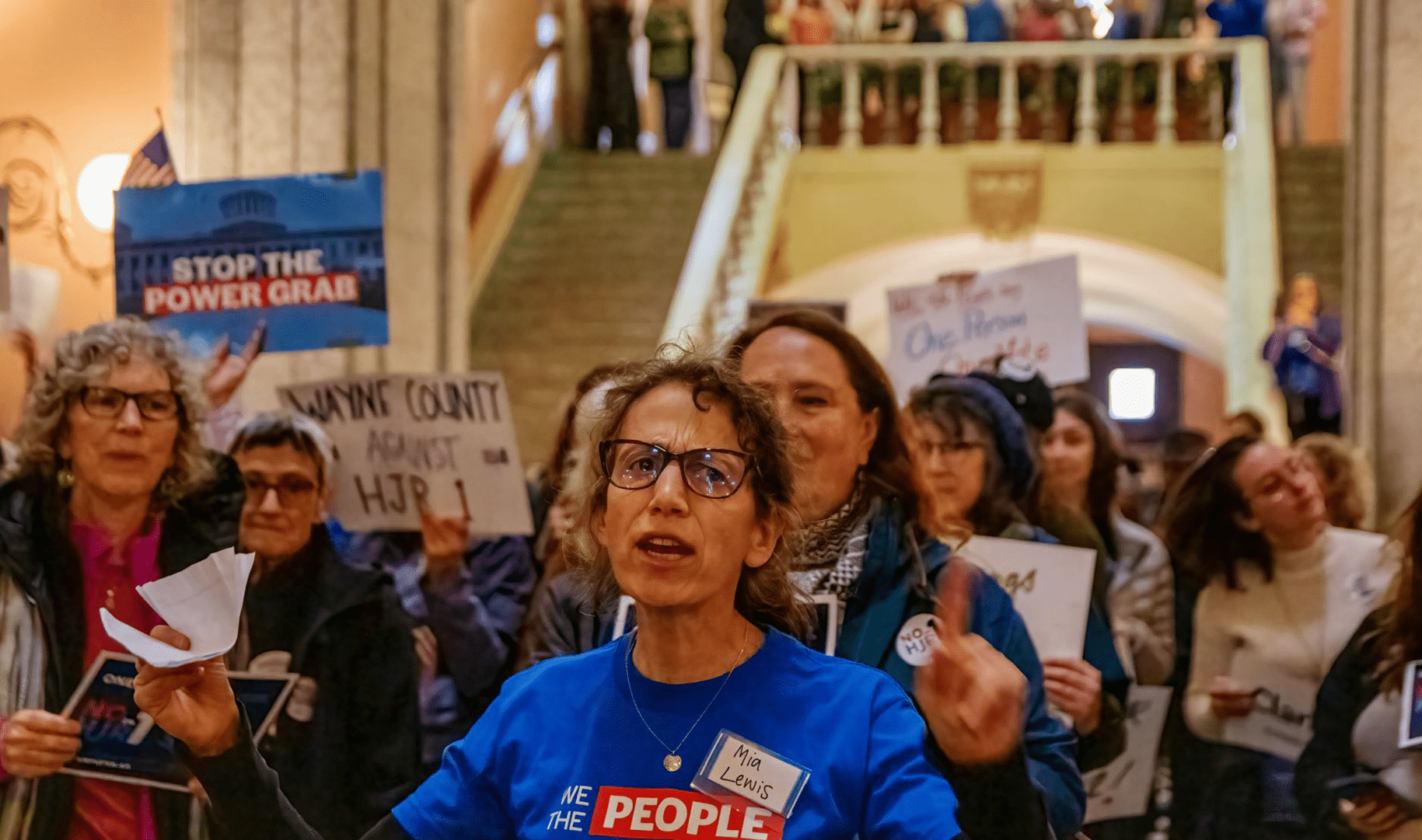

Kwami Abdul-Bey, who has fought restrictions on direct democracy for years as the elections coordinator at the Arkansas Public Policy Panel, shares Miller’s alarm about these reforms’ “chilling effect.” He told Bolts, “These bills, the accumulative effect is death by a thousand cuts.”

A string of states, usually ones governed by the GOP, have tried to restrict direct democracy in recent years, including in Arizona, Idaho, Ohio, and South Dakota. Mississippi even eliminated all popular initiatives altogether in 2021. Some of these proposals sprang up after progressive wins in the 2010s increased the minimum wage and expanded Medicaid, but the dynamic has escalated since the Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision in 2022. Faced with proposals to protect abortion access, conservatives have rushed to make it harder for voters to adopt initiatives.

Proponents of these bills say the changes are necessary to ensure that referendums are trustworthy and deter fraudulent petitions. “They’ll bring a higher level of integrity to the initiative process,” Hammer said of his Arkansas package in February. His critics say state officials already have the tools to go after fraud if they suspected it’s happening. “If these lawmakers are truly worried about petition fraud, they could prosecute people who commit petition fraud right now under our laws,” said Gennie Diaz, a spokesperson for Arkansas for Limited Government, the coalition that sponsored last year’s abortion rights measure. “That’s not what this really is about.”

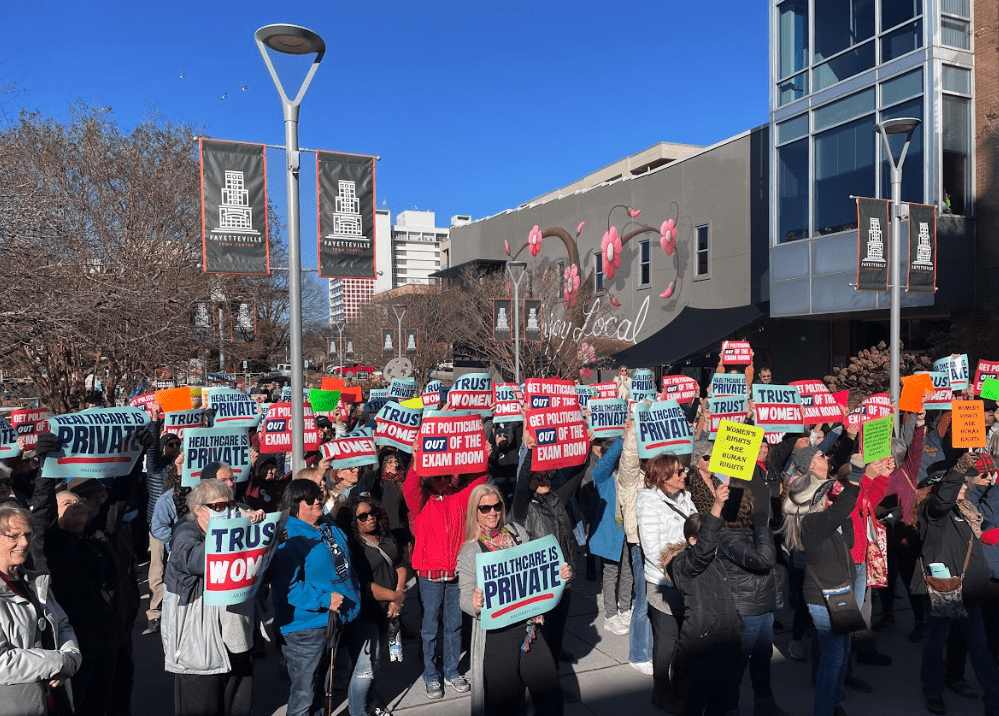

Heading into 2025, Diaz’s coalition said it would try organizing an abortion rights measure in Arkansas again. She suspects that the new bills are an effort to block this repeat effort. “In our opinion, this is really about stifling the process itself,” she said.

Last summer, Arkansas for Limited Government submitted over 100,000 signatures to put a measure on the ballot that would legalize abortion in the first 18 weeks of pregnancy, reversing the near-total ban in place since 2022. But Secretary of State John Thurston declared that the group had failed to properly include some of the required paperwork and disqualified roughly 14,000 signatures, enough to push the measure under the threshold it needed to reach. The state’s conservative-leaning supreme court upheld his move in a 4-3 ruling in August.

Thurston’s actions followed a separate confrontation between this group and Attorney General Tim Griffin at the front-end of the process. Before organizers could start collecting signatures, Griffin repeatedly blocked their proposed text. While he ultimately greenlit its third version, advocates said at the time that he made them waste precious time. Groups that tried to qualify other measures for the ballot last year also complained that Griffin ran out the clock on them.

Griffin and Thurston have said their opposition to abortion did not influence their decisions. The secretary of state’s office, now headed by Jester since Thurston became the state’s treasurer in January, reiterated that position this week. A spokesperson told Bolts the office “makes decisions based on merit, not our own beliefs.” The attorney general’s office did not reply to a request for comment.

Diaz views the matter differently, telling Bolts, “We really saw it as using bureaucratic power and bureaucratic maneuvers to achieve the outcome that they wanted politically.”

Republican Senator Bryan King says he would have opposed the abortion rights measure if it had made it onto the ballot last year—but he also says organizers have the right to put it there, and that the initiative process has become way too difficult.

“I am pro-life, but I am first and foremost for the process,” he told Bolts. “I just believe that citizens have a right to vote for things, and it may be even things I disagree with.”

King voted against most of the new bills targeting direct democracy in this session, one of a handful of GOP senators to do so. “That’s clearly stepping way over the line to me,” he said. Pointing to the proposed requirement that signatories read petitions in full he said, “Hell, we don’t even read every bill that we vote on right now.”

King does not trust the state to implement the new rules fairly. There is “no question,” he said, that future attorneys general and secretaries of state will stretch their powers and toss out ballot initiatives they dislike based on their “personal opinions.”

Still, King voted for one of Hammer’s bills, the one requiring petitioners to show a photo ID. King last decade was one of the architects of the state’s voter ID law, a major conservative win, and he doesn’t think it’s a significant imposition to ask people to show such a document. Critics say the rule will de facto exclude Arkansans who don’t possess an ID, and even those who may not be carrying it on them when they come across a canvasser.

King has spoken in favor of direct democracy for years. In 2023, he joined the League of Women Voters in suing the state of Arkansas over a law that already made it tougher for organizers to put an initiative on the ballot.

That law capped years of Republican efforts to raise the threshold of signatures that a measure must collect. In both 2020 and 2022, the GOP advanced constitutional amendments making it harder for initiatives to pass, but voters rejected the amendments both times. In 2023, GOP legislators changed their strategy. Instead of proposing yet another change to the constitution, they adopted a regular law that contained some of the reforms that Arkansans had just rejected. They forced organizers to collect a set, large number of signatures in 50 of the state’s 75 counties, up from 15; that significantly ratchets up the resources a campaign needs.

King and the League of Women Voters’ lawsuit against the 2023 law is still waiting for a ruling by a trial court judge.

Miller expects that the League of Women Voters of Arkansas will file more lawsuits against the laws that are passing this year. She says they infringe people’s right to political speech, and that they violate the state constitution’s provision that lawmakers may only pass laws to “facilitate” the initiative process.

The Arkansas constitution does guarantee an expansive right to direct democracy, so the legislature cannot outright ban initiatives or block citizens from using that option. But advocates are making the case that the accumulation of rules amounts to a near-ban and violates the spirit of the state constitution.

“Our state motto is regnat populus, which means ‘the people rule,’” Fults said. “With them destroying the ballot initiative process, no longer do the people rule. We will get whatever rights the legislature and the government choose to give us.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.