Ahead of Mayor Race, Noncitizen New Yorkers Grapple with a Voting Policy Failure to Launch

For a brief moment, it seemed some noncitizen New Yorkers may gain the right to vote locally. But with the law struck down earlier this year, they remain at the margins.

| October 22, 2025

This article is also available in Spanish: Leer en español.

Antonio Alarcón, 30-year-old based in Queens, counts himself as a supporter of Zohran Mamdani’s bid for New York City mayor for a number of practical reasons, like strengthening city school funding, including increasing teacher pay, and other quotidian matters. “He has been able to connect with voters, because they know that the housing crisis is going on, they know about childcare,” he said.

But he won’t be able to cast his vote for Mamdani, or anyone for that matter, come Nov. 4.

A DACA recipient who arrived in New York City in 2005 as a child from Mexico, Alarcón has been a longtime vocal immigration and community advocate and organizer. But he’s also part of a chunk of the population that is mostly excluded from the electoral conversation—despite representing about a seventh of the adult population—for the simple reason that they are noncitizens. This group of New York City residents cannot vote, as much as they otherwise affect and are affected by city politics.

As one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit challenging Trump’s first-term attempt to terminate DACA, which ultimately resulted in a 5-4 Supreme Court victory for DACA recipients, Alarcón had a more direct hand in national politics than most people. Yet he cannot cast a ballot to pick his city’s next leader in a race that has generated worldwide interest due to the sharp contrast between Mamdani, the Democratic nominee and self-identified democratic socialist, Andrew Cuomo, the former governor now running as an independent, and Republican nominee Curtis Sliwa.

“Cousins in Mexico are asking me, ‘oh, who are you going to be voting for?’ and I’m like, well, first of all, I can’t vote,” he said. “I’ve been politically involved not because I wanted to, but it was mainly by force, right? Being undocumented pushes you to be politically involved around how people make decisions about your life… For me it’s always kind of been that irony of me running campaigns, ensuring that we get the right people, but not being able to vote.”

For more stories on local elections, subscribe to our newsletter

For a short period in time, it looked like this election cycle might be different. Shortly after the last mayoral election, the city council passed a law to allow noncitizens with some type of work authorization to participate in local elections for mayor, council, and some other municipal positions. The reform would have affected permanent residents, work visa holders, people with Temporary Protected Status, DACA, and residents with some other types of legal status, with the idea that they should be able to weigh in on the local political matters that affected them most directly.

The law was meant to apply this year, massively expanding New York City’s electorate. But opponents of the law sued, and it was struck down by courts repeatedly, finally losing at the state’s highest court earlier this year and leaving a large group of would-have-been voters shut out once more.

“I think had [the reform] actually been implemented, we would have seen tens of thousands of New Yorkers who have been locked out of participating within civic life really pumped to vote, regardless of the election or who was on the ballot,” said Murad Awawdeh, president of the New York Immigration Coalition, which was involved in the push to pass the law. “I think the bigger piece here is that people just want an avenue to exercise their civic duties.”

In recent years, outlets including this one have highlighted communities excluded from the ballot box, often formerly incarcerated people barred from voting by myriad state restrictions. In New York City, the noncitizen population is characterized not just by this inability to vote, but by its sheer breadth and integration into the culture and economy. Nearly 40 percent of the city’s population is foreign-born, with about 14 percent being adult noncitizens, per American Community Survey data.

City estimates put the number of noncitizens who’d have been affected by the reforms somewhere in the ballpark of 800,000 people, or roughly the entire population of San Francisco. They’re in every census tract in the city, with some neighborhoods like Corona in Queens or Sunset Park in Brooklyn featuring tracts that are 50 percent or more noncitizen. It is an immense and immensely diverse constituency, united by its inability to engage in the most direct form of self-governance, representative elections.

What their electoral preferences would be is hard to say. Steven Romalewski, director of the City University of New York’s Mapping Service and Center for Urban Research who helped Bolts analyze the census data, explained that it’s a bit of a catch-22: Electoral surveys and polling are almost always designed to focus on likely voters, definitionally excluding noncitizens given that they are unable to participate.

“Maybe they would vote the same way, or generally the same way, as the communities in which they live, but you don’t know that,” said Romalewski.

We do know how Yogi Pratama, a postdoctoral fellow and senior scientist at the Department of Surgery at NYU Medical Center, feels. He is a Mamdani supporter who has spent some four years in the city doing potentially lifesaving work researching aortic aneurysm, a silent killer.

The work visa holder was raised Muslim in Indonesia before getting his PhD in Italy and then coming to New York City, and is impressed that fellow Muslim immigrant Mamdani has bucked some cultural gravity to support the queer community, of which Pratama is a part, and become a progressive politician.

“I arrived in this country right after Biden got elected, and this is the first experience for me to be in this country and to see political changes this year from America that I used to see back in 2021,” he said. “When it comes to New York as a fortress of progressivism, I always think, this is the last sanctuary when everything in this country turns to a direction that is the opposite of progressive values. I think this is going to be the last city that sustains that.”

For him, this goes beyond slogans to practicalities like rising costs of living since his arrival. He also worries that some noncitizens tune out of civic participation and the future of the city because they think, “I’m not going to vote anyway. So why do I need to care?”

Pratama’s support is consistent with what we can extrapolate from existing polls of New York City voters. Romalewski explained that polls which break down respondents by ethnicity and race could serve as our closest proxy for noncitizen voter surveys. A recent Marist poll, for example, found that likely Latino voters, in a matchup between Mamdani, Cuomo, and Sliwa, heavily favored Mamdani at 50 percent, with 20 points going to Cuomo. A separate Quinnipiac poll had Mamdani winning by a smaller 19-point margin among Hispanic voters, but crushing Cuomo by a staggering 48 points among Asians.

Mamdani’s primary victory was driven at least in part by not just turning out existing voters but new ones via a robust ground game that targeted many immigrant-heavy neighborhoods. It was a marked change from most NYC elections, which typically see abysmally low rates of turnout, with those who do cast ballots often being older voters from wealthier neighborhoods and college grads, while a huge chunk of working-class and voters of color are tuned out from politics. This year’s primaries did not completely reverse that trend, but they did represent the highest turnout for a citywide election in over a decade, including remarkable gains among young voters; voters aged 18 to 29 nearly doubled their 2021 participation, from about 18 percent to over 35 percent, representing the highest turnout of any age group.

Mamdani’s general election strategy seems to still be predicated on bringing new voters in, and it stands to reason that this effort would have brought in some number of noncitizen voters, had they been able to participate as the 2021 reform intended them to.

Randy Frazer, executive director of the youth civic engagement organization YVote, said his organization had been hoping to harness that energy to engage some of their noncitizen members. “We are in a moment of just trying to energize young people, combating both misinformation and disenfranchisement amongst the young people, and we know that they have traditionally either not been included in conversation, or are apathetic,” he said.

There are also some reasons to think that noncitizens would have had special motivations to turn out in this election, happening against the backdrop of the Trump administration’s extraordinarily aggressive immigration crackdown. Mayor Eric Adams, who grew close to Trump this year while successfully lobbying the Justice Department to drop corruption charges against him, has moved to increase the city’s cooperation with Trump’s enforcement apparatus, including a botched attempt to reopen an ICE office on the Rikers Island jail complex.

While a lot of the city’s sanctuary protections are codified into law, there are some things a mayor can do to either confront or tacitly permit the sorts of militarized raids and pervasive federal agency presence that has already come to other cities including Los Angeles, Chicago, Washington, D.C., and Portland. These options include having local police impose some restrictions around warrantless arrests and potentially on federal agents wearing masks. Mamdani in particular has pledged to use the powers of the office to curb potential federal efforts, a position for which Trump has threatened to have him arrested.

For many workers, local electoral results can also be much less abstract and far more immediately tangible. Bhairavi Desai, head of the New York Taxi Workers Alliance, estimates that some 60 to 70 percent of her roughly 25,000 taxicab drivers are noncitizens with work authorization. She pointed out that her members’ livelihoods are directly affected by decisions at the Taxi and Limousine Commission, whose members are all appointed and confirmed by local elected officials.

In her view, this becomes a labor issue, and one of political imbalance. “The workers are directly regulated, or there’s licensing, or there’s tax breaks that the corporations vie for, and without the worker really being able to make their own demands and to leverage politics for better working conditions,” she said. “So much of our economy is political.”

The prospect of noncitizen participation in municipal elections had been a long time coming in New York City. The argument in favor is relatively simple: For a country founded on the principle of no taxation without representation, there are millions of people nationwide that are very much taxed and very much do not have the ability to directly select their representation. Municipal elections in particular revolve around issues far removed from questions of foreign policy or national allegiance; people are interacting with the police, with the education system, with their local roads and hospitals regardless of their citizenship status.

Noncitizen voting in local elections was common during the 18th and parts of 19th centuries, and some pioneering municipalities like Takoma Park, Maryland, revived the practice in the 1990s.

The issue picked up steam in New York City towards the end of Trump’s first term, buoyed by progressive energy and the sense that noncitizens needed a stronger political voice in the aftermath of an administration that made targeting them a touchstone. Although lame duck Mayor Bill de Blasio never quite blessed the measure, he ultimately didn’t block it and the bill sailed through the council at the end of that year. (The ordinance actually became law at the beginning of Eric Adams’ mayorship.)

This culmination of years of effort turned out to be more flash in the pan than earthquake. Weeks after the law was passed, a coalition of Republican legislators including U.S. Representative Nicole Malliotakis, de Blasio’s 2017 opponent in the mayoral race, and Councilmember Joe Borelli, a prominent local Trump surrogate, sued to block it. A state judge struck down the law by June of 2022, and it worked its way up through the appeals process until this judgement was finally reaffirmed by the state’s highest court this March.

The case essentially came down to a line in the state constitution that reads, in part, “every citizen shall be entitled to vote at every election.” The law’s proponents argued that this guaranteed citizens’ right to vote but did not exclude others from participating, while opponents contended that this was effectively a limitation, implying only citizens had this right. Courts ultimately agreed with the latter interpretation, which means that there’s no law that the city council or even the state legislature could pass that could enact a new noncitizen voting system without pushing through a change to the state constitution, which there appears to be little appetite for.

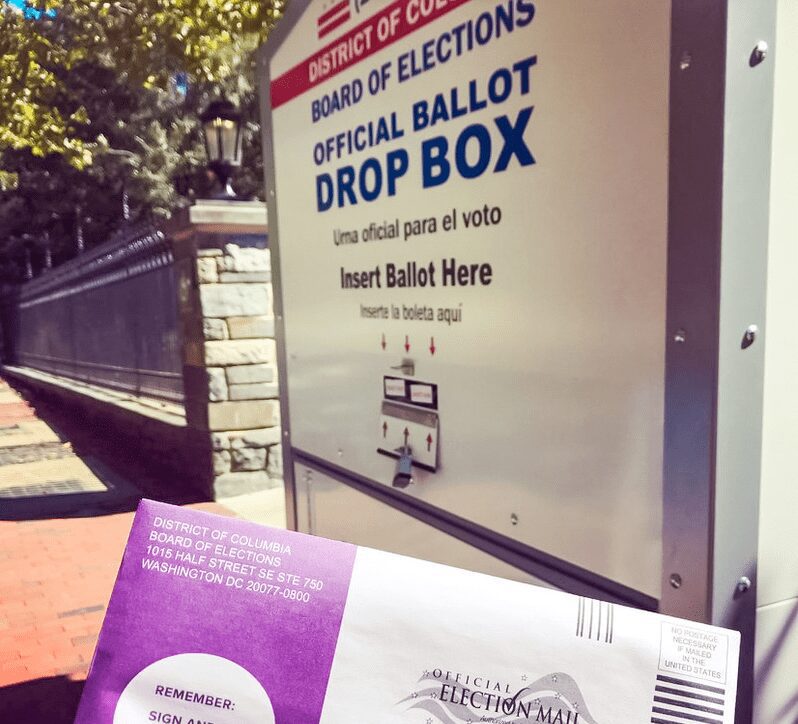

Since this effort, several other municipalities have passed noncitizen voting laws, including Washington, D.C., and several towns in Vermont. But in New York City, noncitizen voting has remained as a sort of strange policy failure to launch.

It was approved at the tail end of one municipal election cycle, not quite fast enough for noncitizens to vote in 2021, and exhausted its appeals just as another cycle was getting underway, three months prior the 2025 primary, slotting neatly between two cycles without noncitizens having the franchise in either one.

Yet noncitizen residents remain deeply involved in political organizing. There’s a long tradition in the city of unions, community groups, ethnic and religious organizations, and so on coming together to advocate and push the powers that be, often winning additional rights and protections for their oft-disenfranchised constituencies. One of the most impressive local political organizing efforts in recent memory was mounted by Los Deliveristas Unidos, a group formed for and by the now-ubiquitous, overwhelmingly immigrant workforce that New Yorkers have come to rely on for instant delivery of food, groceries, and other goods. The group went from concept to securing a historic minimum wage and other benefits in just about three years.

Today, living costs are top of mind for Janna Elizabeth De La Cruz Perez, a new Brooklynite and permanent resident from the Dominican Republic who works the graveyard shift cleaning office buildings to make ends meet and help provide for her 8-year-old son, who remains there. She pointed to New York’s congestion pricing toll. “In addition to fuel, which is already pricey, you have to pay to be able to leave the boroughs, you have to pay back in, you have to pay to go to work, and everything is getting more expensive.” (it’s worth noting that congestion pricing is a state, not city, program.)

De La Cruz is part of the massive and politically potent 32BJ SEIU service workers’ union, which she credits with helping her show the power of political organization and efforts even if she can’t vote in the forthcoming election. She’s participated in union elections and has seen how through its efforts “we get better salaries and benefits.” The union is also offering her legal assistance to sponsor her son to join her in New York, meaning she is thinking about not just her future, but her kid’s.

“What I can say is that we, the residents, contribute something very important to this country,” she said. “We work hard, and we pay a lot of taxes.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.