Tensions High on Bail and Policing as New Yorkers Elect DAs and Sheriffs

Our guide to the flashpoints that will define the 2023 elections, from two NYC boroughs to Troy and Binghamton, and to the muted contrasts elsewhere in the state.

| May 22, 2023

Shortly after the murder of Tyre Nichols by Tennessee police officers in January, people gathered to commemorate his death hundreds of miles away in Broome County, an upstate New York community rocked by a separate police use-of-force scandal just weeks earlier in Binghamton. The police set out to disperse the protest and arrested 14 people, among them Matt Ryan, a local attorney and the former Democratic mayor of Binghamton.

Ryan says he was there to monitor the police behavior toward protesters, standing removed from the gathering. “I said, ‘Okay, I’ll go watch,’ because police have a tendency to overreach to these little things,” he recounts. “I don’t think I should have been arrested. But I was.” The police initially accused him of resisting arrest but they later admitted that this characterization was incorrect and apologized; still, they maintained trespassing charges.

A few weeks later, Ryan announced his candidacy for Broome County district attorney. He says he’d bring into the office a more skeptical perspective toward the criminal legal system, born of his experience as a defense attorney and public defender. “We all know that they police certain communities and treat certain communities differently,” he told Bolts. “If you’re not in a position of power to change it, then it’s not going to change.”

He added, “The only one who is a gatekeeper to make sure that horrible jobs aren’t done is the district attorney because he or she has the ultimate discretion on whether to prosecute and how to prosecute, and what justice to extract from each individual situation.”

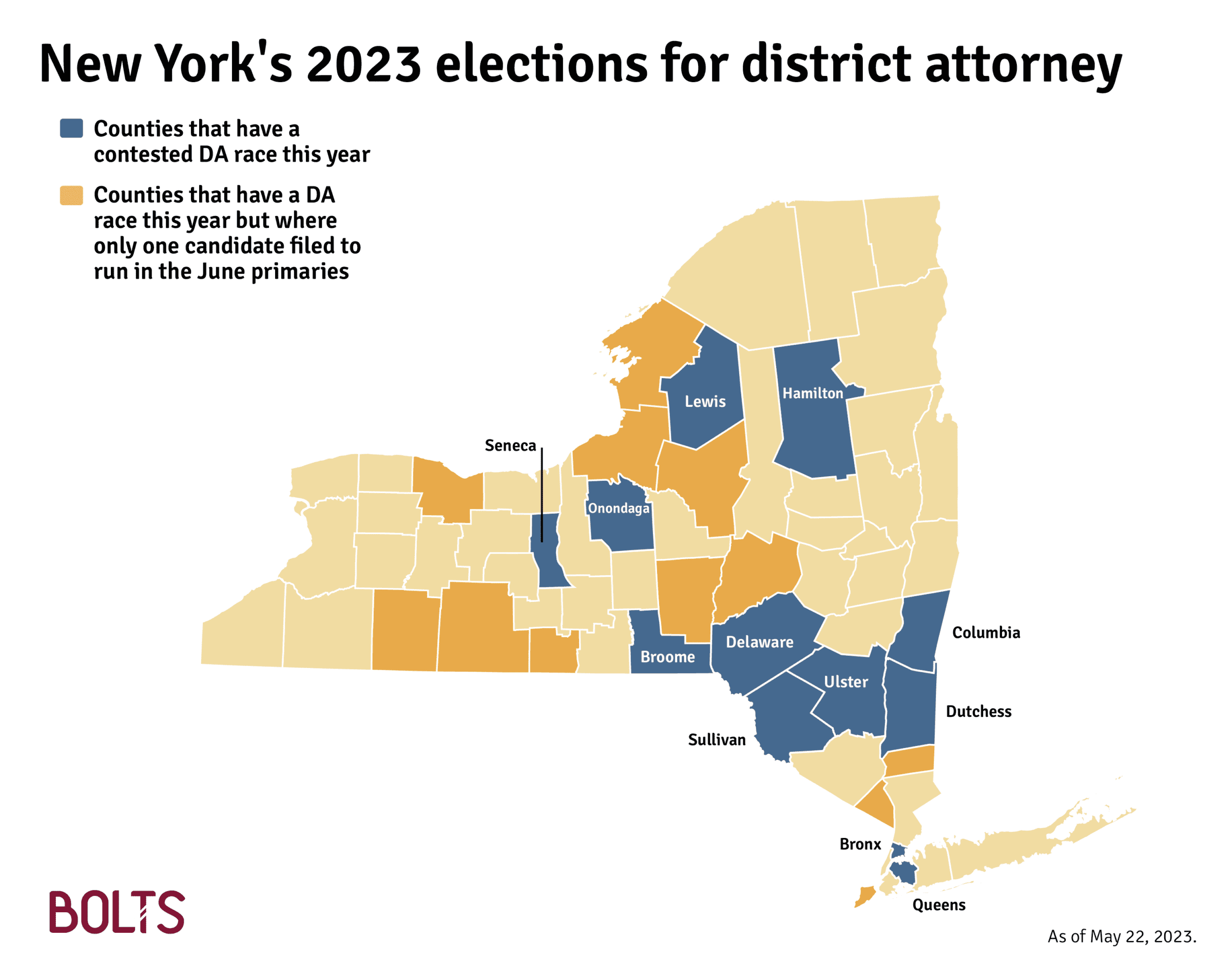

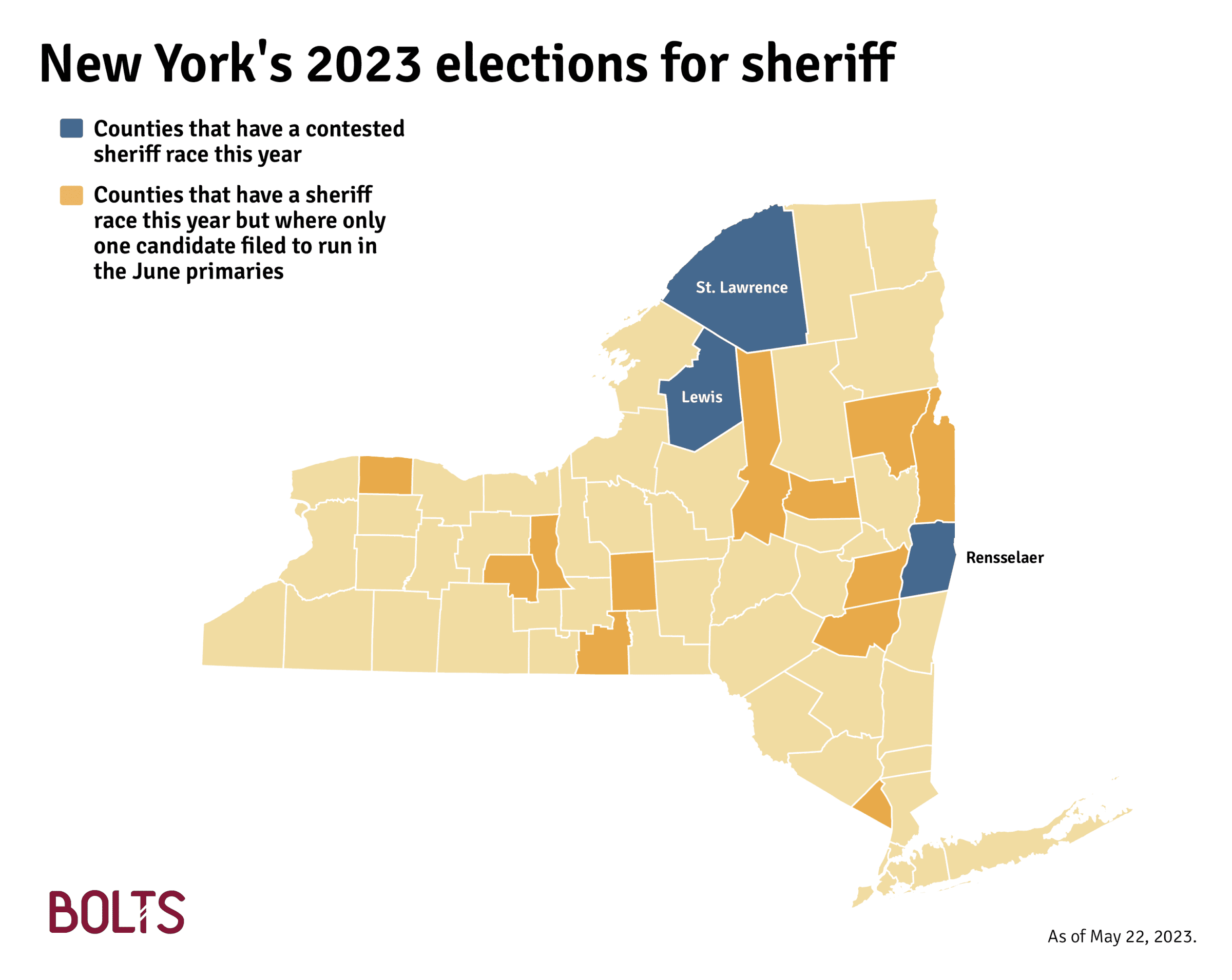

Broome County’s DA race is among dozens this year that will decide who leads local prosecution and law enforcement in New York. Fifteen counties are electing their sheriffs and 24 their DA, and the filing deadline for candidates to run for a party’s nomination passed last month.

Most counties drew just one candidate who’ll be facing no competition. They include conservative sheriffs who have resisted gun control, the high-profile DAs of Rochester and Staten Island, and a sheriff who defied calls to resign for sharing a racist social media post—and is now poised to stay in office for four more years.

Still, a few flashpoints have emerged. Candidates are taking contrasting approaches on bail in Broome, discovery reform in the Bronx, and policing in Queens. Rensselaer County (Troy) faces another reckoning with its unusual decision to partner with federal immigration authorities.

Bolts has compiled a full list of candidates running in the June 27 primaries, which will decide the nominees of the four political parties that have ballot lines in New York State: the Democratic, Republican, Working Families, and Conservative parties. Candidates can still petition until late May to appear on the Nov. 7 ballot as an independent.

These elections are unfolding against the backdrop of reforms the state adopted in 2019 to detain fewer people pretrial and offer defendants more access to the evidence against them. Democrats earlier this month agreed to roll back those reforms after years of pressure by many DAs and sheriffs. Their new package, championed by Governor Kathy Hochul, gives judges’ more authority to impose bail, amid other provisions that will likely increase pretrial detention. Hochul also backed a push by New York City DAs to loosen discovery rules requiring that prosecutors quickly share evidence with the defense, but the final legislation did not touch those.

Tess Cohen, a defense attorney and former prosecutor who is running for DA in the Bronx, is one of a few candidates this year who is voicing support for the original pretrial reforms and distaste for the rollbacks. Cohen is running in the Democratic primary against Bronx DA Darcel Clark, who was reported by City & State to be the chief instigator in lobbying state politicians to loosen discovery rules. (Clark and other city DAs flipped on their push in the final days.) Cohen faults state politicians for making policy based on the media blowing up specific instances of crime.

“The problem with people like the governor bowing down to press coverage that is sensationalist and fear-mongering, and almost always inaccurate, is that we actually make our communities less safe when we do that,” Cohen told Bolts. “We have very good data that shows that holding people at Rikers Island on bail or low level crimes does not make us safer.”

A study released in March by the John Jay College found that people who were released due to the bail reform were less likely to be rearrested.

Eli Northrup, a staunch proponent of the original reforms as policy director at the Bronx Defenders, hopes that the upcoming elections usher in more local officials who are “looking to change the system, shrink the system, work toward having fewer people incarcerated, rather than using it as a tool for coercing pleas.” But he is also circumspect after the new rollbacks. Even if a reformer were to win an office, he says, they’d likely have to contend with police unions, mayors, and other entrenched powers looking to block reforms. “What we should be doing is spending less money on policing and prosecution and investing that very money into the communities that are harmed the most by violence,” he says.

To kick off Bolts’ coverage of New York’s criminal justice elections this year, here are five storylines that jump out since the filing deadline has passed.

1. Challenges from opposite directions for two New York City DAs

Queens four years ago saw a tense Democratic primary for DA between Tiffany Cabán, a public defender who ran as a decarceral candidate, and Queens Borough President Melinda Katz, who prevailed by just 60 votes. Four years later, Katz faces a primary challenge from her right from George Grasso, a retired judge and former NYPD official, who is calling for harsher policing and thinks the city is waging a “war on cops.” Grasso is running with the support of Bill Bratton, the former NYPD commissioner and a frequent critic of policing reforms.

Public defender Devian Daniels is running as well, saying she wants to fight mass incarceration from the Queens DA’s office after “years of witnessing abuses on the front lines as defense counsel.” The Democratic primary typically amounts to victory in this blue stronghold.

In the Bronx, Darcel Clark’s sole primary challenger, Tess Cohen, says wants to take the DA’s office in a more progressive direction. She says that Clark’s lobbying to loosen the state’s discovery rules is emblematic of how prosecutors can coerce defendants into guilty pleas. “If you’re held in Rikers, and you can only get out if you plead guilty, and you can’t make that argument that you’re actually innocent because you don’t have the evidence, then you end up pleading guilty just to get out of Rikers,” she told Bolts.

Cohen explained that she would also change how the office decides whether to recommend for pretrial detainment. “If we are in a space where our recommendation for sentence or our plea offer means the person is immediately going to be released from jail, they should be released anyways,” she said. “You should not be holding someone in jail that you plan to release the minute they plead guilty.”

Clark did not reply to a request for comment.

2. North of New York City, the policy contrasts on pretrial reform are muted

Broome County, on the border with Pennsylvania, had the highest rate of people detained in jail as of 2020, the year the reforms were first implemented, according to data compiled by the Vera Institute for Justice. Ryan, the Democratic lawyer running for DA, told Bolts he supports the reforms, crediting them for helping slightly reduce the local jail population.

But his two Republican opponents in this swing county disagree. Incumbent Michael Korchak has pushed for their repeal for years, while his primary rival Paul Battisti, a defense attorney, says the reforms were “extreme.” Neither Battisti nor Korchak replied to requests for comment. Their rhetoric is in line with the position of many, but not all, upstate DAs who have lobbied to roll back the pretrial reforms ever since they passed in 2019.

But candidates have tended to converge on pretrial policy in the other DA races north of New York City. There are three such counties besides Broome with more than 100,000 residents.

In Ulster County, Democrat Manny Nneji, who is currently the chief assistant prosecutor, faces Michael Kavanagh, who used to have the same job and now works as a defense attorney, and is running as a Republican. In interviews with Hudson Valley One earlier this year, both candidates largely agreed that the 2019 bail reform should be made more restrictive, and jostled about who is tougher on crime.

In Onondaga County, home to Syracuse, Incumbent William Fitzpatrick is running for re-election as a Republican against Chuck Keller, who filed to run for the Democratic nomination but also that of the Conservative Party, an established party in the state. (New York law allows candidates to run for multiple nominations at once.) The Syracuse Post-Standard reports that the local Conservative Party in March chose to endorse Keller over Kitzpatrick after Keller shared with them that he supports bail reform roll backs in line with what lawmakers ended up passing in early May. (Christine Varga is also running in the Conservative Party primary.)

In Dutchess County, Republican William Grady is retiring this year after 40 years as DA, a tenure during which he strongly fought statewide reform proposals. Democrat Anthony Parisi and Republican Matthew Weishaupt, who have both worked as prosecutors under Grady, are running to replace him; after he entered the race, Parisi faced a threat of retribution from Grady, for which the DA later apologized. Weishaupt has said he thinks the discovery reforms are “dangerous” in how they help defendants. Parisi did not reply to questions on his views on the reforms.

Six smaller counties—Columbia, Delaware, Hamilton, Lewis, Seneca, and Sullivan, with populations ranging from 5,000 to 80,000 residents—also host contested DA races this year.

3. Half of this year’s DA elections are uncontested

A single candidate is running unopposed in 12 of New York’s DA races. Ten of them are already in office, but two are newcomers: Todd Carville in Oneida County and Anthony DiMartino in Oswego County. Both are Republicans and currently work as assistant prosecutors.

Michael McMahon, Staten Island’s DA, is running unopposed for the second consecutive cycle: He is a Democrat in a red-leaning county, but the GOP did not put up a candidate against him. He has been very critical of the criminal justice reforms adopted by his party’s lawmakers, and has pushed for their rollback. Another prominent critic of the pretrial reforms, Monroe County (Rochester) DA Sandra Doorley, is also running unopposed. Doorley, a Republican who was the president of the state’s DA association back when the reforms were first implemented in 2020, faced a heated challenge four years ago but is now on a golden path toward a fourth term.

4. Will ICE’s 287(g) program retain a foothold in New York?

Rensselaer County, home to Troy, is the only county in New York State that participates in ICE’s 287(g) program, which deputizes local law enforcement to act like federal immigration agents in county jails—and one of the only blue-leaning counties in the nation with such an agreement. Immigrants’ rights activists from Cape Cod to suburban Atlanta have targeted 287(g) by getting involved in sheriff’s elections in recent years, tipping these offices toward candidates who pledged to terminate their offices’ partnerships with ICE.

Patrick Russo, the Republican sheriff who joined 287(g), is retiring this year. The race to replace him will decide whether ICE’s program retains its sole foothold in New York.

But will anyone even make the case for breaking ties with ICE? The two Republicans who are running for Russo’s office, Kyle Bourgault and Jason Stocklas, each told Bolts that they would maintain their county in the program with no hesitation.

The only Democratic candidate, Brian Owens, did not return repeated requests for comment. He said at a press conference last month that he had no position on the matter. “I’d want to educate myself a little more before I’d make any decision on that,” he said. Owens is a former police chief of Troy, a city that during his tenure saw local activism pressuring officials to not collaborate with ICE, so these are not new questions. Still, Russo coasted to re-election unopposed four years ago, and it remains to be seen whether the 2023 cycle gives immigrants’ rights activists any more of an opening.

5. Most incumbent sheriffs are virtually certain of securing new terms

Albany Sheriff Craig Apple drew national attention in 2021 for filing a criminal complaint against then-Governor Andrew Cuomo for groping, but he also attracted criticism for fumbling the case. The New York Times reported at the time that Apple seemed to be made of Teflon, having rebounded from past controversies with multiple re-election bids where he faced no opponent. History repeated itself again—he drew no challenger this year.

But judging by the lay of the land throughout the state, this says less about Apple than it does about a broader dearth of engagement in New York’s local elections: Overall, 80 percent of the state’s sheriff races are uncontested this year.

This includes the sheriffs of Fulton and Greene County, who have fiercely opposed a new gun law banning concealed weapons in a long list of public spaces, alongside many peers who are not up for election this year. Fulton’s Richard Giardino took to Fox News to signal he’d only loosely enforce it.

And it includes Rockland County Sheriff Louie Falco, who faced calls for his resignation in 2020 after he shared a link from a white supremacist website about Black people on Facebook. Three years later, he won’t even face any opponent as he coasts to a fourth term.