“Nobody Knows What That Means”: The Murky Decisions of New York’s Parole Board

New York advocates hope to force their state to be more forthcoming about how it decides parole grants, worried that incarcerated people don’t know how to apply or to secure release.

| December 18, 2023

This is the third installment of a collaboration between Bolts and New York Focus on the opaque institutions that make up New York’s parole system. Read the first and second installments.

Editor’s note (Dec. 19): In deciding the case described in this article, the New York Court of Appeals ruled on Dec. 19 that the state does not need to release the Board of Parole training documents.

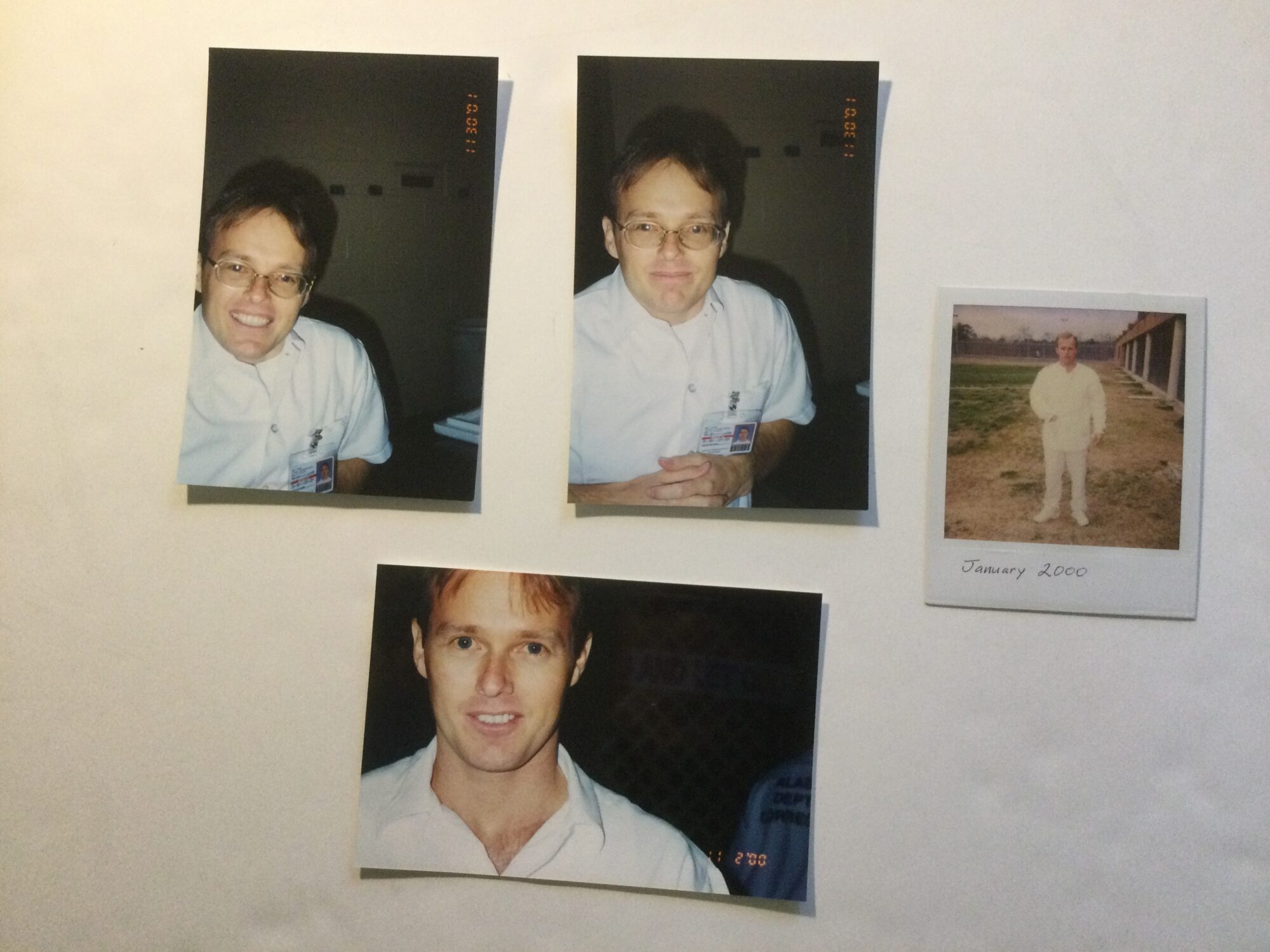

Anthony Dixon was sure the parole commissioners would give him a “fair shake.” As a young man, Dixon was convicted of robbery, gun possession, and murder. After serving his minimum sentence of 30 years, he had extensive evidence of his transformation to present to the New York State Board of Parole.

“I came into prison at 20, 21 years old and I went before [the board] as a man in my 50s, as a changed person,” Dixon told Bolts and New York Focus. While incarcerated, he developed anti-violence and anti-drug programs and worked toward a college degree. Prison staff wrote letters commending his character and accomplishments.

The parole board rejected his application anyway—and Dixon said it barely explained why. The decision’s vague phrases and boilerplate language gave no indication of what he could have done differently, he said, and he had no clue how to prepare for his next hearing. It took him two more years of fighting to secure his release.

Since his release, Dixon has helped organize efforts to make New York’s parole system easier for incarcerated people to navigate and more transparent, assailing the board’s bare-bones justifications for its rulings. Now, he and other advocates want to crack down on the board’s opacity.

“This system is killing hope, and in some instances, it does cause some people to take their lives,” said Dixon. “This is not just death by incarceration. It is specifically death by the parole board.”

Over 10,000 people appear before New York’s parole board each year. Hearings are often rushed, lasting an average of 15 minutes. Commissioners are afforded wide discretion in how they decide cases, with little oversight or review. They decide to keep around 60 percent of parole seekers in prison.

New York Focus and Bolts reviewed dozens of parole board decisions and appeals. The decisions run as short as a single paragraph, providing parole seekers little guidance on how to win their release. Many repeat variations of the same vague phrases when denying release, many lifted directly from the state’s parole statute. Applicants are often informed that their release “is not compatible with the welfare of society” for example, without explaining how the board arrived at that conclusion.

“They’re not giving people any clarity about what they can do to obtain parole the next time,” says Michelle Lewin, executive director of the Parole Preparation Project. “They’re not giving individualized reasons for denials, despite the fact that their own internal regulations demand that they do so.”

The parole board’s lack of transparency creates difficulties for applicants of all stripes. But it especially burdens parole seekers serving lengthy sentences for violent crimes. Despite decades of incarceration, these individuals face the very real possibility of dying in prison, even if they have demonstrated sincere growth and rehabilitation.

“I think it’s time that we gave people a chance to be productive citizens,” said Assemblymember David Weprin, a Democrat who has introduced legislation to increase the parole board’s transparency, “especially in the case when they’ve shown that … they’re not the same individuals that they were when they committed the crime 20 years ago, 30 years ago.”

Advocates for reform have sought to strengthen board oversight from every angle: legislation like Weprin’s, direct pressure on Governor Kathy Hochul, and cases before the Court of Appeals.

Last month, Appellate Advocates, a non-profit organization of public defenders, argued before the state’s highest court that the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision should release the training documents it provides to board members. The documents include hypothetical decisions and sample language—all materials that parole advocates say could help incarcerated individuals understand how the board makes decisions and how to make the strongest case for release.

DOCCS has resisted, and argued in court that it should be allowed to shield the documents, in a dispute that has dragged on for over five years.

Jose Saldaña, the director of the Release Aging People in Prison campaign, described a similar experience with the board. He spent decades incarcerated in New York, in his case for the attempted murder of an NYPD sergeant when he was 27 years old. Though he had earned his associate degree and led several restorative justice and victim awareness programs, the parole board denied his release four times.

“We discussed these vague reasons … ‘releasing you at the time would so deprecate the nature of the crime as to undermine respect for the law’,” Saldaña said. “What does that really mean?”

“Nobody knows what that means,” Steven Zeidman, director of the CUNY School of Law’s Criminal Defense Clinic, told Bolts and New York Focus. Not even parole commissioners. Zeidman said commissioners apply the same language differently from one another, even when evaluating the same individual. “What’s the message to people inside preparing? How do you prepare?”

New York law requires board members to consider many enumerated factors in their decisions, but the commissioners frequently emphasize the nature of the parole seeker’s offense over their rehabilitation and growth while incarcerated. Their cases are often dismissed with terse lines like “your positive programming to date is noted.”

Reform-minded lawmakers have long supported Weprin’s bill, the Fair and Timely Parole Act, which would reduce the board’s opacity and limit some of the commissioners’ discretion. The legislation would eliminate the vague statutory language cited in board decisions and require commissioners to explain in “detailed, individualized, and non-conclusory terms” exactly why they decided to deny release. It would also require the board to issue a quarterly report that includes the reasons for each denial, which commissioners were assigned to each case, and how they voted.

The bill would establish a presumption that the board would grant parole once an applicant has served their minimum sentence. To deny release, parole commissioners would have to clearly articulate how a parole seeker threatens public safety.

Weprin, a Democrat, first introduced the bill in 2017. Since then, three separate iterations have died in committee, where the 2023 version now sits. Dixon attributes the icy reception in Albany to upstate conservative legislators — whose constituents disproportionately benefit from employment opportunities in the prison system. “Upstate districts have a vested interest to keep this no-sense institution going,” he said.

Senator Patrick Gallivan, the chamber’s Republican minority whip, is a former parole commissioner who opposes the Fair and Timely Parole Act. His district encompasses Erie County’s Collins Correctional Facility, a medium-security prison employing hundreds of people. But he said his opposition to the bill has nothing to do with protecting upstate jobs.

Gallivan said the bill would limit the board’s ability to consider negative aspects of the parole seekers’ applications, such as their institutional records. He agrees with reformers that the Board of Parole has too much discretion — but he sees them stretching the rules to grant release, rather than keeping people in prison. Gallivan said that when he was a parole commissioner, he tried to set his biases as a former sheriff and state trooper aside and vote according to the law. He said he wants everyone on the board to do the same. Some commissioners say at their confirmation hearings that they will abide by the law, he said, but “the minute that they got sworn in, they said, ‘I don’t care what the law is. I’m here to release people and I’m going to.’”

Reform advocates have repeatedly called on Hochul to reform the parole system. As New York Focus and Bolts have previously reported, the board features zombie commissioners serving long past their terms have expired and a medical parole system that leaves most terminally ill people to die behind bars. The vacancies on the board have long afforded Hochul the opportunity to staff it with reformers. But Wanda Bertram, a spokesperson for the Prison Policy Initiative, said she does not expect Hochul to expend any of her political capital on the issue. Under Republican pressure, she noted, Hochul has supported other rollbacks to criminal justice reforms in recent years.

Hochul has pointed to fluctuations in crime and rearrest rates when backing down from other reforms. But Bertram claims that lenient parole policies don’t undermine public safety. She points to a federal study showing that people who commit violent offenses are the least likely to be rearrested after release. “The safest person you can release from prison is a murderer, especially someone that served 10 to 20 years,” said Bertram. “That’s just what the data shows.”

Hochul’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Frustrated by New York’s legislative and executive branches, parole reformers have turned to the judiciary. The state’s courts have limited power to modify parole board decisions, but advocates hope they will at least compel the board to be more transparent.

At a November 15 Court of Appeals hearing, Appellate Advocates argued that the state’s Freedom of Information Law mandates the release of the board’s training documents.

DOCCS revealed the existence of the training materials in 2020 when they told Appellate Advocates they were withholding certain documents in response to a records request. Michael Higgins, assistant director of the University at Buffalo Law School Civil Rights and Transparency Clinic, says that administrative agencies routinely prepare interpretations of the law that govern what they do, but they often keep the interpretations secret. “Basically, they make up rules that are written down in their training documents or in manuals that the public can’t access,” he said. He says FOIL requires the release of those documents upon request.

At the hearing, DOCCS argued that FOIL does not extend to the training materials because a parole board lawyer prepared them, shielding them from disclosure under attorney-client privilege. (DOCCS declined to comment due to ongoing litigation.) Appellate Advocates countered that attorney-client privilege covers legal advice on real-world scenarios, not abstract training documents.

While the Court of Appeals has shown signs of a leftward shift on some criminal legal issues, it’s unclear whether the newly reconfigured court will flex its power on behalf of parole seekers. During oral argument, Associate Judge Shirley Troutman, a Hochul appointee, expressed concerns that ruling for Appellate Advocates would foist an “unreasonable burden upon trial courts” handling future disputes over attorney-client privilege. Even Chief Judge Rowan Wilson, the court’s liberal leader, said Appellate Advocates’ arguments had “frightening” implications for attorneys. The court scarcely touched on how its decision would impact incarcerated individuals.

For advocates like Dixon, obtaining the release of these documents would only be a first step. Achieving a truly transparent parole system would require wholesale changes, from data disclosure to board appointment procedures.

“The matrix itself needs to be dismantled,” Dixon said. “The system has to change because it is criminal what is happening.”

Stay up-to-date

Now is the best time to support Bolts

NewsMatch is matching all donations (up to $1,000) through the end of the year. Support our nonprofit newsroom today.