Inside the Urgent Campaign to Commute North Carolina’s Entire Death Row

Death penalty opponents hope to persuade Democratic Governor Roy Cooper to grant mass clemency before he leaves office next year, worried that a Republican takeover could restart executions.

Kelan Lyons | December 11, 2023

This article was produced as a collaboration between Bolts and NC Newsline.

Every night one of his neighbors was scheduled to be executed by the state of North Carolina, Glen Edward “Ed” Chapman would look up at the window slit in his cell and say to the black sky, “I’ll see you again.”

Saying goodbye was hard. Chapman and his peers who were also condemned to die formed a small community within the prison system. And whenever the state executed someone, that community would shrink by one member.

“I was close to those guys on death row,” Chapman said. “They were like family.”

One of the people killed while Chapman was on death row was Ernest Basden, sentenced to death in 1993 in a murder-for-hire scheme. After he got to prison, Basden stopped using alcohol and drugs and found God. His family had traveled around the state to build public pressure to convince then-Governor Mike Easley to grant Basden clemency and spare his life.

They failed. One cold winter evening, Basden’s family huddled in the mailroom of Central Prison in Raleigh to say goodbye, able to freely talk with and touch him in the last hours of his life.

“My mom had not hugged him in 10 years,” said Kristin Stapleford, Basden’s niece.

Basden was executed in the early morning of Dec. 6, 2002.

More than 20 years later, Chapman is on the other side of the bars, having been exonerated and released from prison, and is now joining Basden’s family in again urging a North Carolina governor to spare the lives of the men and women sentenced to death.

“We promised him that we would not give up the fight, that we would fight to see the death penalty abolished in North Carolina,” Stapleford said.

Stapleford and Chapman are members of a coalition of more than 20 social and criminal justice organizations and religious leaders calling on Governor Roy Cooper, a Democrat, to commute the sentences of the people on North Carolina’s death row to prison terms before he leaves office at the end of 2024. A Bolts and NC Newsline analysis shows there are currently 136 people on this death row—the fifth-largest number in the U.S.—whose lives would be spared if Cooper were to act.

Commutation is one form of clemency, a broad power most U.S. governors have to change a person’s criminal conviction or prison sentence, most often due to individual circumstances of a person’s incarceration; whether they were convicted as a youth, for example. Former North Carolina Governor Terry Sanford, who held the office from 1961 to 1965, saw his clemency power as a form of grace.

“It falls to the governor to blend mercy with justice, as best he can, involving human as well as legal considerations, in the light of all circumstances after the passage of time, but before justice is allowed to overrun mercy in the name of the power of the state,” Sanford wrote in 1961, after shortening the sentences of 29 prisoners through executive clemency.

But what Cooper is being asked to do now is much broader.

This coalition of activists is calling on him to commute death sentences as an act of racial justice. In North Carolina—a state where people were legally enslaved for more than 100 years—just over 22 percent of residents are Black, but over half of those on death row are Black or African American, according to figures provided to Bolts and NC Newsline through a public records request. Of the dozen people who have been sentenced to death in North Carolina and later found innocent, 11 are people of color.

Advocates are now hoping Cooper will offer clemency for the 136 people on death row en masse, regardless of the circumstances of the crimes of which they are convicted, because of the injustices of the death penalty and North Carolina’s criminal legal system at large.

Granting clemency would not mean that the people on death row would be released from prison, nor would it mean the abolition of the death penalty going forward. The state constitution only grants the governor discretion to shorten a sentence as he sees fit. Cooper could, for instance, commute the sentences to life without the possibility of parole. Or, he could sentence them to life and leave the possibility of parole open.

It’s similar to a petition made by advocates in Louisiana, who earlier this year asked Governor John Bel Edwards to commute the sentences of more than 50 people on that state’s death row. So far this mass request has been blocked by the Louisiana Board of Pardons.

While North Carolina governors frequently granted clemency in the late 1970s until 2000, commutations became rare starting in 2001.

Executions have slowed as well—North Carolina hasn’t executed anyone since 2006, and North Carolina’s district attorneys pursue the death penalty at a much lower rate than in years past. But with Republicans controlling the state supreme court and holding supermajorities in the House and Senate, many anti-death penalty advocates are concerned that they could restart, especially if a Republican moves into the executive mansion.

The death penalty has been raised as a talking point in early debates among Republican gubernatorial candidates and has been an issue in previous elections as well. In 2017, top Republican legislators demanded Cooper and Attorney General Josh Stein, a Democrat now running for governor, resume executions after four prisoners at Pasquotank Correctional Institution were charged with killing four employees in a failed escape attempt.

Two of those four men have since been sentenced to death.

A new governor couldn’t simply sign a slip of paper and reopen the execution chamber since the courts are the reason for the pause in executions. There are ongoing legal battles over the application of the Racial Justice Act, landmark legislation that gave people an opportunity to get off death row if they could prove racial discrimination had played a role in their death sentence. Democrats passed that bill in 2009, Republicans repealed it in 2013. Then, when Democrats controlled the state supreme court in 2020, it struck down the retroactive repeal of the law, allowing the claims that had already been filed to continue to play out through the present day.

But conservatives now control the state supreme court, and advocates worry they could revisit that ruling, clearing a path to resume executions. There are also still legal questions about North Carolina’s protocols for using lethal injection drugs to carry out executions, though advocates worry North Carolina Republicans could find a way around that, as they have tried to in South Carolina and Alabama.

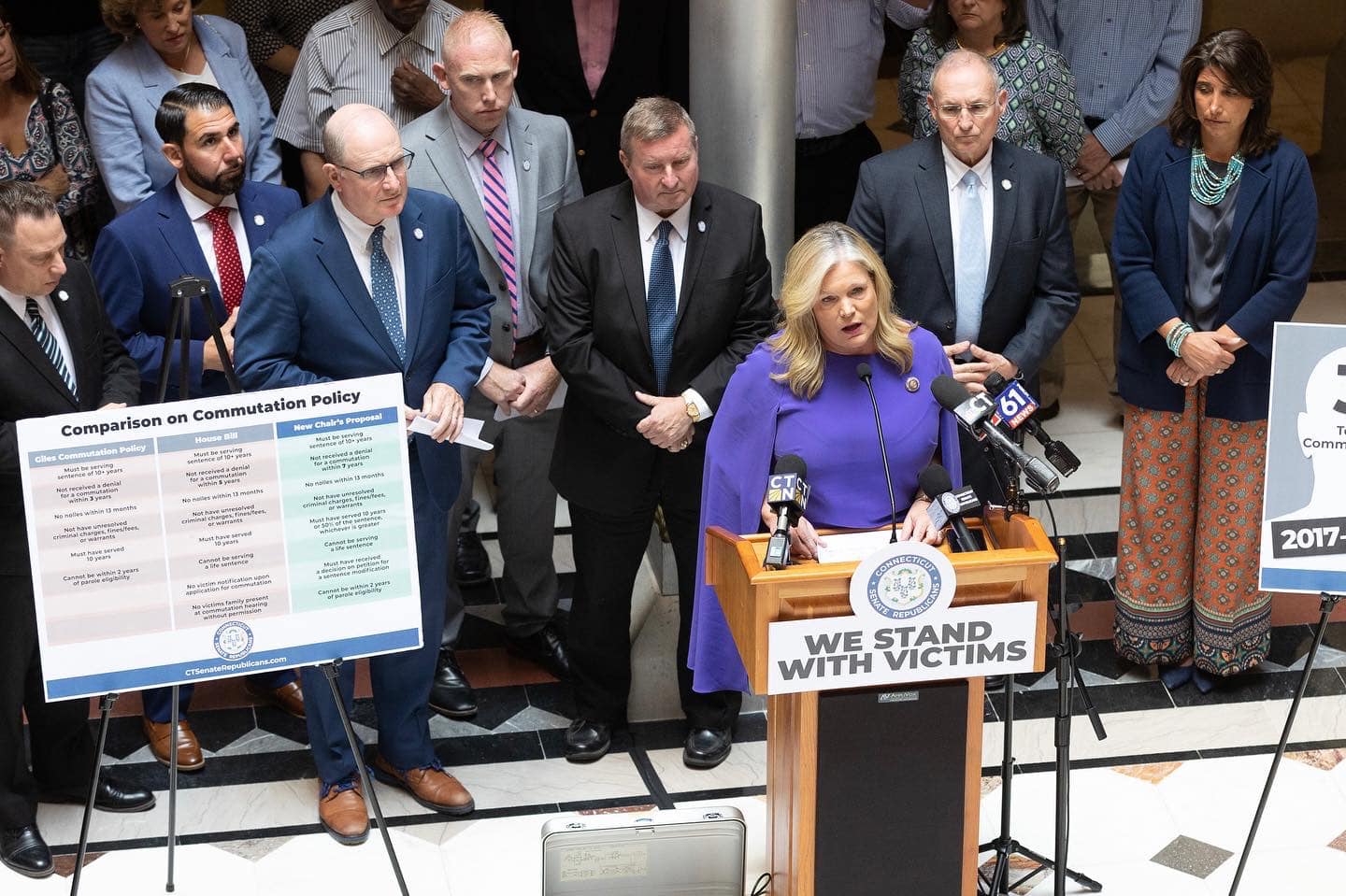

Republican control of the other branches of state government has given those opposed to the death penalty a sense of urgency. At a recent rally, Kristie Puckett, the senior project manager of Forward Justice, told a crowd of around 200 supporters that Cooper was their last hope because of North Carolina’s current political climate.

“We can’t trust our legislature. We can’t trust the courts,” she said. “And so we are forced to rely on Governor Cooper.”

The coalition has staged marches, written letters and met with the governor’s staff. They’ve held film screenings on the “Racist Roots” of North Carolina’s death penalty and handed out postcards so residents can write Cooper directly. Soon, they’ll post billboards and travel to communities across the state to build support for the campaign as it enters its final year before Cooper leaves office.

“Our commutations campaign is very focused on 2024 because we have a sense of urgency that executions could resume, as they did in the federal system,” said Noel Nickle, executive director of the North Carolina Coalition for Alternatives to the Death Penalty. “I am concerned that the political climate of our state has become more entrenched in policies and practices that would lead to executions resuming.”

Cooper, who has had a mixed record on commutations, has been pressured for years by criminal justice reformers, many of whom have gathered outside the governor’s mansion annually calling on him to use his clemency powers. Cooper didn’t grant any commutation until March 2022—two years into his second term—shortening the prison terms of three people who committed crimes when they were children. In December 2022, after three weeks of protests outside his home, Cooper commuted the sentences of six more people.

So far, Cooper has made no public comment on the 136 currently on death row. In 2017, after the murders at the prison in Pasquotank, a spokesperson for the governor said Cooper supported the death penalty and had a “long history of upholding it” during his 16 years as attorney general. The governor’s spokesperson did not answer recent questions from Bolts and NC Newsline on whether he still supports the death penalty or if he was considering commuting North Carolina’s death sentences.

Puckett credited the annual campaign for getting Cooper to issue commutations last year. She doesn’t think he would have exercised clemency otherwise.

“That’s the only reason he’s doing something: because he’s forced to do something,” she said.

A lasting legacy

The North Carolina governor’s office is weak by design but clemency is one area where the executive branch has broad authority to commute prison sentences without approval from a parole board.

“This is a rare policy area where the governor has power, can exercise it, and doesn’t need to ask anyone else for permission,” said Christopher Cooper, a professor of political science at Western Carolina University (who has no relation to the governor).

Even so, it would be novel for a Democratic governor—especially in the South—to use their power to unilaterally empty their state’s death row. Louisiana’s John Bel Edwards, tried to grant the mass clemency request he received before he left office, but he was ultimately thwarted by the state board of pardons.

Cooper has already laid the groundwork for clemency on a systemic level. In June 2020, just after a white Minneapolis police officer murdered George Floyd, the governor established a Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice that he asked to make recommendations for ending racial disparities in the criminal justice system. One of the subjects they tackled was the death penalty.

Ken Rose, who was a senior attorney at the Durham-based Center for Death Penalty Litigation for 35 years before retiring in 2017, gave a presentation to members of the task force in November 2020 showing two strikingly similar maps of the United States: One showing where Black people were lynched across the nation between 1883 and 1940, an another marking the execution of Black defendants between 1972 and 2020.

Later that year, the task force published a report noting the death penalty has a “relationship with white supremacy.” They did not recommend abolishing capital punishment, but they did propose ways to narrow its use.

The task force also identified commutation as a remedy to address injustice, suggesting officials examine commuting sentences of people sentenced to death before July 2001, when North Carolina had a “quasi-mandatory” death penalty law that forced prosecutors to seek a death sentence in capital cases. More than two thirds of the people on the state’s death row are there because of that law, according to Rose.

“You have a lot of people on death row, still on death row, who wouldn’t be there if DAs had a choice for pleading cases to life,” he said.

Following another recommendation of the task force, Cooper created the Juvenile Sentence Review Board in 2021, which reviewed the sentences of people who committed crimes as children and recommended suitable applicants for clemency. Of the nine commutations Cooper granted in 2022, five were based on recommendations from that board. In a press release, his office acknowledged science showing children’s brains are different than adults’, and that state and federal laws treat minors differently in sentencing in criminal cases.

“As people become adults, they can change, turn their lives around, and engage as productive members of society,” Cooper said in a press release.

Kerwin Pittman, one of the members of the task force, thinks Cooper’s own political ambitions could make him reticent to use clemency more broadly. At 66 years old, he is a relatively young politician and could have decades left in public office.

“To just issue a blanket clemency to everybody, or commute everybody, he may not feel that is in his best interest,” Pittman said. “I’m sure he doesn’t want to make a misstep that’s going to come back and bite him.”

But this reluctance is frustrating to advocates who see Cooper as wasting his authority to commute sentences as he sees fit.

“Why do you work so hard and be so shrewd to get to the top just to piss the power away?” Puckett asked.

The exonerees

More than 20 organizations from across the state and country are working with the North Carolina Coalition for Alternatives to the Death Penalty to persuade Cooper to use his clemency powers. Members of the European Union also came to Raleigh in November to meet with Cooper and Attorney General Stein to talk about the death penalty.

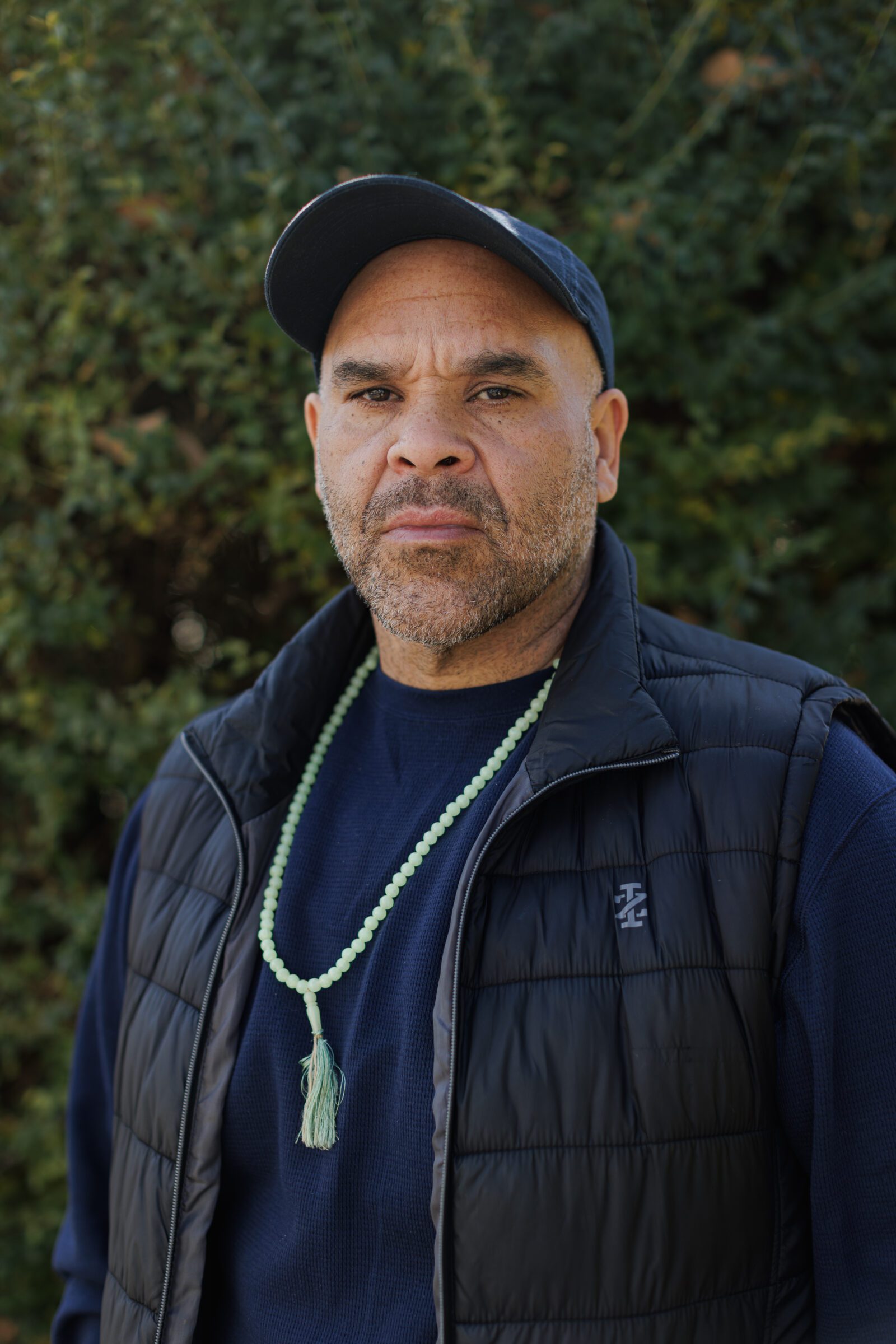

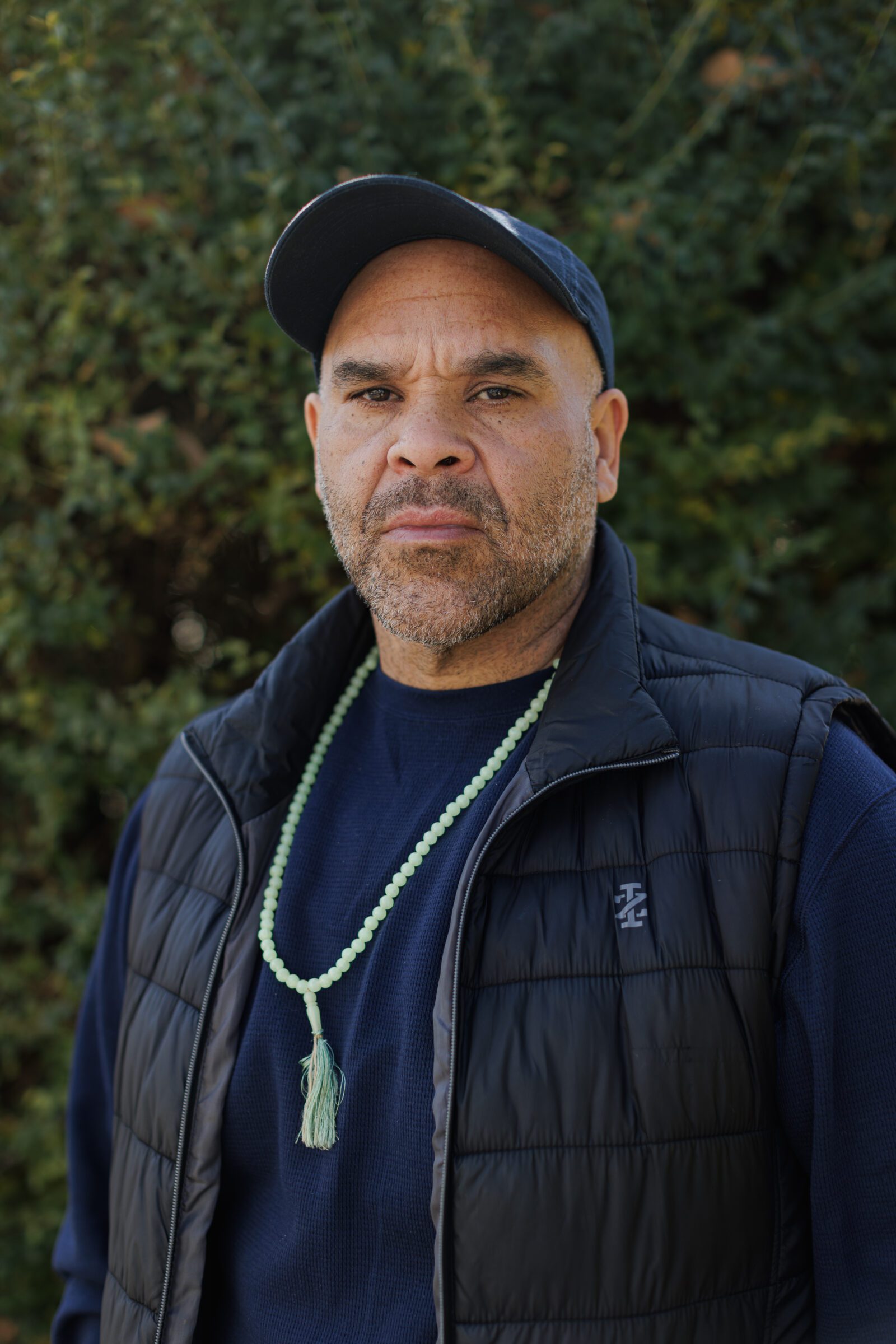

But it is exonerees like Alfred Rivera and Ed Chapman who are leading the charge—men who intimately know the hopelessness of death row but escaped it once they proved they should have never been convicted.

Rivera is both a victim of violence and wrongful incarceration. After his father was killed in a robbery when Rivera was a toddler, his mother, left alone with five children to care for, started drinking. She died from cirrhosis of the liver seven years after her husband passed away.

“This is the toll that it took on her,” Rivera said.

Two decades later, a jury sent Rivera to death row, convicting him for murder. But he was exonerated in two years, after the state supreme court ruled he should get a new trial because jurors hadn’t heard evidence suggesting he’d been framed.

Chapman, meanwhile, spent 14 years on North Carolina’s death row before being exonerated in 2008 after a judge ordered a new trial and a district attorney dropped the charges. He had been sentenced to death for two murders he didn’t commit. There were serious issues with the investigation; police had withheld evidence, and a detective later faced perjury charges for lying on the stand.

Chapman struggled after he came home. He lost a job, isolated himself and used drugs and alcohol to cope. He moved to Florida, staying in a spate of recovery houses before sleeping on the streets for about a year.

He felt guilty about how he was living, like he was wasting the second chance he’d been given. “I let those people down that fought for me,” he said.

The guilt, shame and remorse compelled Chapman to join the commutation campaign after he moved to Durham in 2022. Now he is fighting for a cause bigger than himself.

“I’m trying to be better than I was before,” he said.

On Aug. 19, 2023, almost 17 years to the day since North Carolina’s last execution, Chapman and the coalition met at Pullen Memorial Baptist Church and marched more than a mile to Central Prison to honor those executed there.

The crowd of roughly 200 held a vigil to remember the 43 people executed by the state since 1984. Dozens of people held signs with the names of those who were killed in the execution chamber within the prison behind them. They also called for an end to death row, chanting at cars driving past them on Western Boulevard.

It was the first time Chapman had been back at the prison since getting off death row. He got chills standing outside, knowing what it was like to live on the other side of the metal doors, behind the barbed wire. But he found strength standing beside death penalty abolition advocates and people like Rivera, those sentenced to death for something they didn’t do.

“I felt that the cause for me being there outweighed my anxiety,” Chapman said.

Innocent people like Chapman and Rivera are easy cases to make to the public. It is harder—and potentially poses a greater political risk—to show grace to those who did their crimes.

Rose has represented many people on death row. He’s found that those individuals can be caring and selfless, thoughtful and resilient. They can also struggle under the weight of the mental illness and the trauma they’ve endured.

“I look at them differently because I’ve gotten to know them,” Rose said. “I think people can do really terrible things. I think people can do monstrous things. But I do not think that that makes them a monster.”

That is a sentiment shared by Lynda Simmons, another member of the commutations coalition. Simmons’ son Brian was murdered by a teenager named James Moore, in 2004. Simmons struggled for years with relentless waves of grief over Brian’s death. But in time, trying to make sense of a senseless act, she connected with Moore, who wound up serving 15 years for second-degree murder. The two traded letters, helping one another process the trauma and grief they’d both endured.

As they were communicating through the mail, Simmons was also doing restorative justice work with people on death row. She’d share her story with the men at Central Prison, helping those sentenced to death connect with someone who had lost a loved one to an act of violence. There, working with men like Moore who had gone to prison when they were teenagers, she could see that Moore had done something terrible, but that action didn’t define his entire humanity.

“Listening to them, I knew that when James murdered my son, that’s what he did,” Simmons said. “I believe with everything in me, that’s not who he was.”

Simmons has always been against the death penalty, but that belief was crystallized when she went to Moore’s sentencing hearing in 2005. When she walked into the courtroom and saw Brian and Moore’s friends and family on opposite sides, she saw the impact of the shooting echoing across generations and familial lines, lives irrevocably changed by a single violent act.

“I knew that they were victims, too,” Simmons said. “They didn’t shoot my son. And I don’t believe that they raised James to shoot my son.”

“I do believe that human beings are able to change,” she continued. “And when we execute people, we rob them of the chance to change.”

Politics vs. reality

Members of the North Carolina Republican Party have long campaigned on their support of the death penalty.

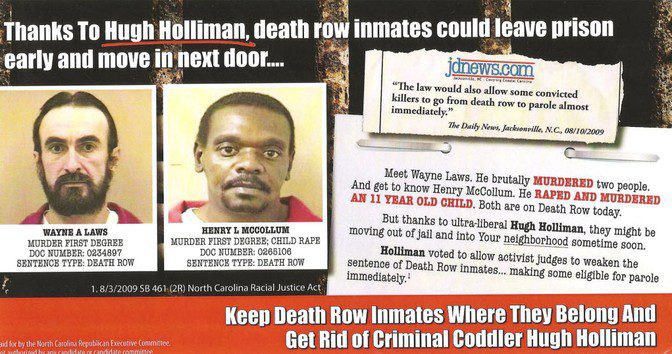

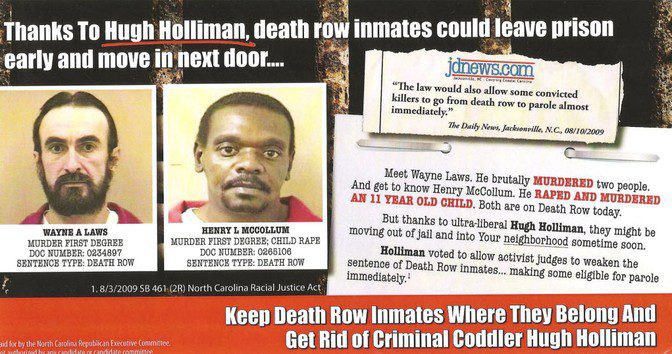

In 2010, the State Republican Party sent out a mailer slamming Majority Leader Hugh Holliman, a Democrat whose teenage daughter was raped and murdered, as a “Criminal Coddler” for helping pass the Racial Justice Act, legislation that offered people a chance to get off death row—but not, as the flier erroneously claimed, out of prison—if they could prove racial discrimination had affected their charging or sentencing.

The front of the flier read: “Meet your new neighbors. You’re not going to like them very much.”

On the back were mugshots of two men sentenced to death: Wayne Laws and Henry McCollum.

McCollum did eventually get out of prison, not because of the Racial Justice Act but because he was innocent, like Chapman and Rivera.

Public support for the death penalty has declined since its peak in 1994, when 80 percent of Americans said they were in favor of capital punishment, and has been on the decline ever since. Now, just over half of Americans support the death penalty.

But in 2010, North Carolina’s politicking over capital punishment worked: Holliman lost the election, as did other Democrats targeted for their support of the Racial Justice Act. Rose said it was impossible to determine whether the misleading flier swung the elections, but it doesn’t change the fact that it was a politically salient issue at the time.

“There was a lot of political use of the death penalty for a long, long time, in a way that arguably shaped elections,” said Rose.

Today, the exonerations of people like Rivera, Chapman and McCollum are eroding public support for the death penalty further, said Rose. But that doesn’t mean Republican politicians won’t bring it up when it is to their political benefit. It resurfaced in 2017 because of the prison escapes, and has been mentioned this election cycle.

During the first Republican gubernatorial debate, one candidate called for resuming executions under the death penalty. Lawyer and businessman Bill Graham polled second in the governor’s race a few weeks after releasing an ad advocating for the death penalty for drug dealers and human traffickers. (He still trailed the Republican frontrunner, Lt. Gov. Mark Robinson, and 42 percent of respondents were undecided, but the director of the Meredith Poll told WRAL the ads seemed to be helping Graham.)

“As a prosecutor, I went after violent criminals,” Graham said in the ad. “As governor, I’ll put ‘em in jail or in the ground.”

The Republican-controlled state supreme court has also shown a willingness to overturn precedents set by previous Democratic majorities. Earlier this year they issued new rulings on partisan gerrymandering and the state’s voter ID law, reversing Supreme Court opinions written in 2022, when Democrats were in control.

“If you were an ordinary court and you were honoring precedent and you were trying to build on that precedent and navigate that precedent, then they have a long, long way to go before they restart executions,” Rose said. “But if what you wanted to do is resume executions and kill the people that are currently on death row, you could do that, but you’d have to ignore the precedent.”

But the politics of the death penalty are often divorced from reality. The most common outcome of a death sentence in North Carolina isn’t an execution, but a long process of appeals that leads to a reversal of a sentence, said Frank Baumgartner, a political science professor at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and a national expert on the death penalty.

“These things are reversed not because somebody put a paperclip on the wrong side of the paper,” Baumgartner said. “They’re reversed because evidence was withheld or because improper instructions were given to the jury, or, you know, something serious.”

Baumgartner maintains an internal database on capital punishment in North Carolina. According to his figures, 411 people have received death sentences since 1976; 190 of them, or 46 percent have been overturned.

Nationally, more than 8,500 people have been sentenced to death since 1972, Baumgartner said, wondering, “What are the odds that every one of them is guilty as charged?”

On death row, community

To live on North Carolina’s death row is to be constantly reminded of one’s mortality. The men housed on death row in Central Prison in Raleigh, can spend years, decades, entire generations together in their communal pod. Most of the people on death row have been there for 20 or 30 years. They grow old together; sometimes they die of natural causes. (There are two women on death row, incarcerated at a different prison.)

“Our memories of the dead become death row lore, significant to us, living on in our hearts and minds and dreams. We live together, die together, mourn together, and remember,” said Lyle May, who has been on death row since 1999.

That quote is included in “Bone Orchard: Reflections on Life Under Sentence of Death,” a book written by one of May’s peers, George Wilkerson, who was sentenced to death in 2006. The book, co-written with Robert Johnson, a professor of justice, law and criminology at American University, is a firsthand account of life on North Carolina’s death row.

Most states keep those on death row in segregation, meaning the incarcerated are locked in their cells most of their days, for decades, until they win their appeals, die or are executed. But North Carolina’s death row is unusual in that it houses condemned people together. The consistent group setting makes people with death sentences in the state particularly suitable for commutation, Johnson argued, saying they have had time to develop social and emotional skills since they spend so much time out of their cells.

“You don’t get the feeling of a pressure cooker on North Carolina’s death row,” Johnson told Bolts and Newsline. “There’s the overshadowing threat of death, but there’s a lot of community.”

There are risks to the incarcerated if their death sentences are commuted. Breaking up the community established on death row, for one. There are also implications for their appeals. People on death row in North Carolina are entitled to attorneys in appellate proceedings. Plus, Johnson said he thinks people facing death sentences typically get more attention on their cases from criminal justice reformers and the media, compared to people serving life.

“That is definitely a valid concern, them losing legal remedies if granted a commutation,” said Pittman, a member of the racial equity task force. “They could lose access to having automatic counsel in the appellate courts, as well as if somebody is on the row and somebody is innocent, they could lose access to their freedom through the court system.”

Even still, Johnson said those on death row stand to gain much from clemency. They could have better access to rehabilitative programming.“We’d been told many times point-blank, ‘You are not here to be rehabilitated,’” Wilkerson writes in “Bone Orchard.”

Receiving clemency would also allow more opportunities for them to see their loved ones because of a less restrictive visitation policy, Johnson added.

And obviously, they won’t have a death sentence hanging over their heads. Only about 20 people have been added to death row since the last execution in the summer of 2006, according to the state’s roster. One of those is Wilkerson, who has been a part of the community since Dec. 20, 2006.

“We live shoulder-to-shoulder for ten, fifteen, twenty, thirty years,” he wrote in the book, “and gradually this me versus them mentality I’d walked in with, melted away, leaving only us.”

Two miles from Wilkerson’s cell, on a warm, wet December afternoon, members of the clemency campaign met in a parking lot across the street from the governor’s mansion. They sang, chanted and chatted about their support for emptying death row. Nickle said the theme of the day was “community, compassion and commutation.”

Cooper has yet to say publicly whether he will commute the death sentences, or if he is even considering such a broad use of his clemency powers. He will leave office at the end of 2024, giving advocates about a year to build support for emptying North Carolina’s death row.

Chapman and Rivera stood in a corner laughing amongst themselves as two people sang “We Shall Overcome” to the crowd. After a few minutes, the exonerees went separate ways. Rivera stepped onto the sidewalk, glancing at the signs that listed the birth date and day of execution of 43 people killed by the State of North Carolina.

The rallies are a surreal experience for Rivera. The names on the signs aren’t just words to him. When he sees or hears the names of people still facing a death sentence, those who haven’t yet been executed, he can still see their faces, and he wonders how they’ve changed in the 24 years he has been free.

“I knew these guys personally,” Rivera said.

He feels a sense of survivor’s guilt for having gotten off death row. He still thinks about what it was like living there, “the horrible conditions,” having to reckon with “how I went from that to this,” as he gestures at the wide open parking lot, the community of supporters.

“Is it fair that people are still suffering under those conditions?” he asked. “I think about that, me being free and at these events.”

Stay up-to-date

Now is the best time to support Bolts

NewsMatch is matching all donations (up to $1,000) through the end of the year. Support our nonprofit newsroom today.