Oklahoma and Oregon Deliver Two Measures Of Relief For People Facing Poverty

Hundreds of thousands will gain access to public health insurance in Oklahoma, and will avoid having their licenses suspended over debt in Oregon.

| July 1, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

Hundreds of thousands of people will gain access to public health insurance in Oklahoma, and will avoid having their driver’s licenses suspended over debt in Oregon.

As the COVID-19 pandemic leaves millions across the country out of work, Oklahoma and Oregon saw a pair of victories on Tuesday for the rights of low-income people.

Oklahoma voters expanded the Medicaid program, the latest triumph for organizers who are putting this issue on the ballot in a string of conservative states.

And Oregon ended the suspension of driver’s licenses over unpaid fines and fe, a practice that can trigger mounting economic and legal trouble for people who cannot afford their court debt. Criminal justice reform advocates now want public authorities to more fundamentally cut off their regressive budgetary reliance on fines and fees.

Oklahoma expands Medicaid

Oklahomans approved a ballot initiative on Tuesday that will expand the Medicaid program, as provided by the Affordable Care Act.

As a result of this narrow vote, an estimated 200,000 people will newly qualify for public health insurance in one of the most conservative states in the country.

The initiative circumvents state Republicans who have long refused to expand the program. Their opposition has left hundreds of thousands of lower-income Oklahomans in a coverage gap, ineligible under current rules and yet too poor to qualify for government subsidies to purchase a private plan. GOP Governor Kevin Stitt opposed the initiative after wavering on weaker expansions over the past year.

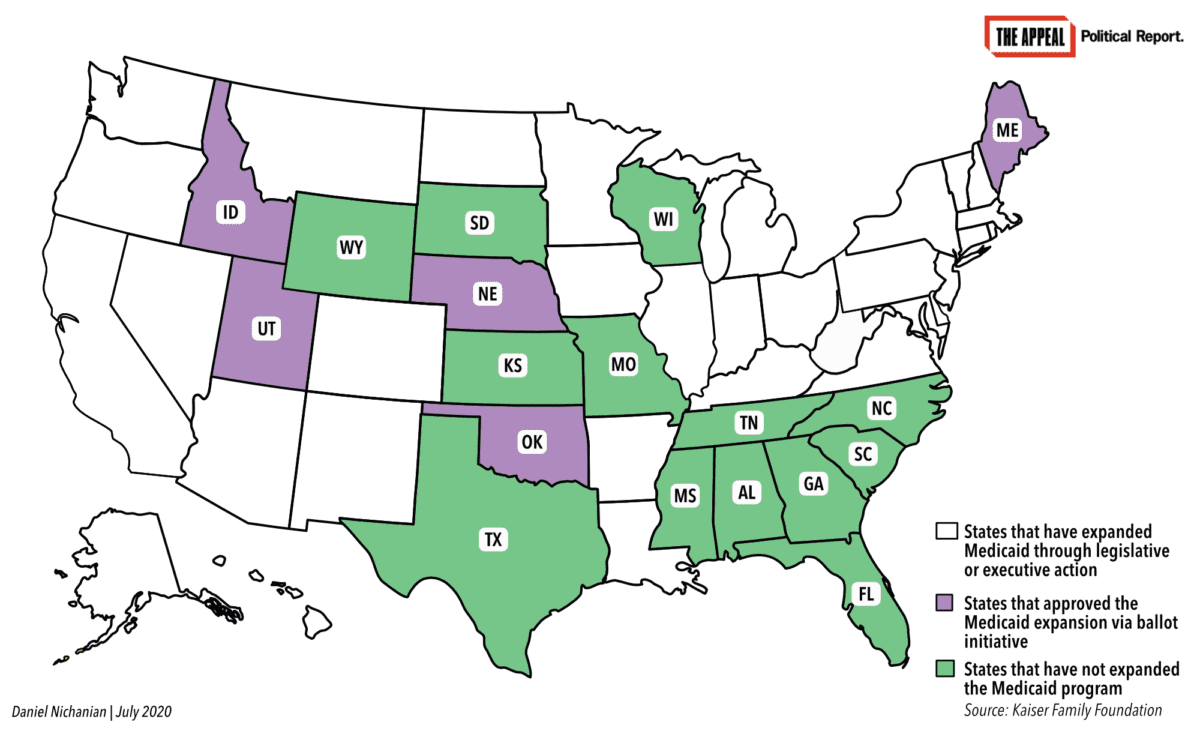

Oklahoma is the fifth state to expand Medicaid through a ballot initiative, after Maine in 2017, and Idaho, Nebraska, and Utah in 2018. Oklahoma’s version amends the state constitution, which will limit the state government’s ability to delay or overturn it, and could hinder potential efforts to add restrictions such as work requirements.

Still, millions nationwide will remain cut off from the Medicaid program because of a failure to expand it in Florida, Missouri, Texas, and 10 other states where Republicans control at least part of the state government. Missouri is voting on an expansion measure of its own on August 4. The Fairness Project, a national group, helped organize Oklahoma and Missouri’s initiatives, and has signaled plans for future pushes in other states.

Besides extending access to healthcare across Oklahoma, the Medicaid expansion could relieve the pains of rural hospitals, who have eyed it as a lifeline for years. Still, the measure was carried by significant wins in the state’s urban cores.

The expansion could also assist efforts to reduce the criminalization of substance use. Without coverage, people are blocked off from treatment, and are often arrested by law enforcement. This connection already resonated in the 2018 campaigns in Idaho and Nebraska, and again in Oklahoma this year. Gerard Clancy, president of the University of Tulsa, made the case last year that expanding Medicaid provides access to medication to fight opioid addiction and ease withdrawal symptoms. In recent years, Oklahomans have repeatedly approved ballot initiatives to ease the state’s punitive approach to drug policy, including a major measure in 2016 to reduce drug possession from a felony to a misdemeanor.

Oklahoma’s elections on Tuesday also saw Mauree Turner, a community organizer who works at the ACLU of Oklahoma, unseat an incumbent state lawmaker in a Democratic primary in Oklahoma City on a platform focused on advancing both criminal justice reform and public health.

“We are currently operating in a system that relies on incarcerating our community members suffering from poverty and mental health issues, rather than dedicating time to provide resources they need,” Turner, who still faces a general election in November, writes on her website. She describes Oklahoma’s failure to expand Medicaid as “carving folks, that are already suffering, out of a chance to seek help if needed.”

On Tuesday, a majority of Oklahomans agreed with her.

Oregon takes a step against the harm of court debt

Oregon will stop suspending driver’s licenses over unpaid fines and court fees.

The Democratic-run legislature passed emergency legislation this week during a special session, and Governor Kate Brown signed the bill into law on Tuesday.

License suspensions affect hundreds of thousands of Oregonians—roughly one in 10 adults, according to state advocacy organizations, a share that is consistent with, if not lower than, in other states—and they compound cycles of poverty. “This is just one of many examples in which we are unnecessarily burdening members of our community to the point of instability and failure,” Bobbin Singh, executive director of the Oregon Resource Justice Center, told me. He views the new law as an important step in “moving away from criminalizing poverty.”

In taking away many people’s main mode of transportation, these suspensions cut off access to work and make it harder for people to pay off debt in the first place.

“If someone is unemployed or underemployed, unsheltered, or has a family, regularly paying fines and fees, much less paying them off, is extremely difficult,” Alexes Harris, a sociologist at the University of Washington who studies monetary sanctions, told me in April when Virginia adopted a similar law. “Adding the burden of suspending or revoking their driver’s licenses creates more disadvantages that have a cascading effect.”

Those who continue using their cars to get to their jobs can get prosecuted for driving on a suspended license, and these prosecutions—much like the original financial obligations—are very racially disparate.

Twenty-six percent of those prosecuted for driving on a suspended license are Black and Native, according to the Oregonian. These groups make up 4 percent of Oregon’s population.

Oregon is the ninth state to prohibit driver’s license suspensions over unpaid fines and fee. It joins California, Idaho, Kentucky, Montana, Mississippi, West Virginia, Virginia, and Wyoming, according to the Fines and Fees Justice Center’s comprehensive national tracker.

Advocates are pushing similar bills in other states, including Illinois and New York.

More work remains in Oregon as well to end the criminalization of poverty, and to break the connection between the unequal criminal legal system and access to transportation. For one, Oregon’s new law does not end the suspension of driver’s licenses over a failure to appear in court.

Moreover, it does not waive the underlying financial obligations, which are disproportionately imposed and universally burdensome.

The COVID-19 pandemic and its economic havoc has added urgency to the fight against the widespread imposition of fines and fees. The Fines and Fees Justice Center, for instance, is calling on state and local governments to discharge all outstanding court debt, or at least suspend its collection.

“There are many insidious fines and fees that only create additional harms, exacerbating instability, and that do not serve the public interest,” said Singh. “My hope that the legislature and advocates will continue to identify these burdens and be equally committed to removing them as they did in this instance.”