Oklahoma Gives Incarcerated Survivors of Domestic Violence a New Chance at Freedom

The Oklahoma Survivors’ Act reduces sentences for people whose convictions stemmed from their abuse. It passed despite prosecutors’ objections and an initial veto by the governor.

| May 24, 2024

On a Wednesday last month, April Wilkens spent her morning glued to the television inside the law library at the Mabel Bassett Correctional Center, Oklahoma’s largest women’s prison. State lawmakers were taking their final vote on the Oklahoma Survivors’ Act, a sentencing reform bill that would give April and other incarcerated survivors of domestic violence a chance at freedom. Wilkens, whose story of abuse helped inspire the legislation, realized it had passed when she started hearing advocates who had attended the vote in person cheering through the speakers.

Cheers soon echoed through the prison as Wilkens spread the news. “There’s been lots of praising the LORD, hugging, high-fiving and crying big happy tears today,” she told Bolts on the day of the vote.

That celebration, however, quickly turned into an emotional rollercoaster for Wilkens and other incarcerated survivors of domestic abuse who had spent the past two years organizing and advocating for the sentencing reforms. The week after that final vote, Republican Governor Kevin Stitt vetoed the bill, despite it receiving nearly unanimous approval from the GOP-run legislature. Stitt, who called the bill “bad policy,” was praised by the state’s powerful district attorneys association, which has fought the resentencing bill for the past two legislative sessions and decried it as “a blueprint for violent criminals looking for yet another opportunity to lessen their sentences.”

Senate Pro Tem Greg Treat, a Republican and the lead sponsor of the bill, quickly moved to override the veto and issued a statement castigating the governor for blocking it. Jon Echols, the Republican House member who carried the bill in that chamber, also vowed to overcome the governor’s veto as the end of the legislative session rapidly approached.

Treat revived the Oklahoma Survivors’ Act last week by attaching it to another bill, this time with language raising the bar to qualify for resentencing—an addition that was necessary to gain the governor’s approval. The legislation again overwhelmingly passed the state Senate and House.

Stitt finally signed it on Tuesday, nearly a month after his initial veto, enshrining the sentencing reform into law.

Wilkens said many of the women around her had given up hope in the days and weeks after the veto. But the cheering resumed inside Mabel Bassett once news of the governor’s signature reached her and other incarcerated survivors. “The cheers that erupted and spread throughout the prison seemed even louder and more exuberant,” Wilkens told Bolts this week, saying other incarcerated women have been approaching her to celebrate the bill’s passage and learn whether it might affect their sentences. “Our victory was even sweeter after being heartbroken by the veto.”

The Oklahoma Survivors’ Act mandates sentencing reductions for people who are convicted and can prove that domestic violence or sexual abuse was “a substantial contributing factor in causing the defendant to commit the offense or to the defendant’s criminal behavior.” The act also allows survivors who have already been convicted and imprisoned to petition a judge for resentencing and release under the new sentencing guidelines.

Stitt’s initial veto threatened to derail the legislation for the second time in as many years. As Bolts reported last year, a similar reform bill stalled after pressure from prosecutors resulted in a watered-down version that wouldn’t have applied retroactively and only gave judges the discretion, but not the obligation, to impose lighter sentences for people convicted of crimes against abusive partners.

The compromise language added to the legislation earlier this month after Stitt’s veto raised the burden of proof for those convicted of violent felonies, such as assault, manslaughter, murder, and robbery. To qualify, they must provide documentation that the victim of the crime was also the perpetrator of the defendant’s abuse, the person who trafficked them, or that their action was coerced by their abuser. Treat, the Senate sponsor, told lawmakers earlier this month, “This clarification does not change the intent of the bill whatsoever.” The new sentencing guidelines and retroactivity remained in the final bill that Stitt signed.

Colleen McCarty, executive director of Oklahoma Appleseed Center for Law and Justice, which has advocated for the reform, told Bolts that the organization had already identified 13 survivors that it plans on representing pro-bono in resentencing petitions that result from the legislation—including Wilkens, who was sentenced to life in prison for fatally shooting an abusive ex-boyfriend who had repeatedly stalked, assaulted, and raped her.

McCarty says none of the cases that Appleseed is working on will be negatively impacted by the language added to the legislation after Stitt’s veto. “My team and the Governor’s staff, as well as Representative Echols and Pro Tem Treat worked on the new language together,” McCarty told Bolts. “I ran many scenarios through the new language and none of the cases we work on would be negatively impacted by the new subsection.”

“The bill retains retroactivity, mandatory reductions in sentences for those who can prove abuse, and prescribed ranges much less than current law,” McCarty said. “I am hopeful my client April Wilkens will get relief and get to experience freedom after 26 years in prison.”

Wilkens’ story is hardly unique in Oklahoma, which regularly ranks among states with the highest female incarceration rate and where the criminal legal system has long been particularly harsh to women. Oklahoma has also maintained one of the country’s highest number of domestic violence homicides: Since 1996, it has been in the top ten states for women murdered by men; in recent years, it ranked second of all 50 states with an average of 114 domestic homicides between 2019 and 2022.

“This isn’t a partisan issue,” McCarty said, noting the bill received overwhelming approval in a legislature where Republicans hold large majorities. “In Oklahoma, it transcended politics because so many Oklahomans have had experience with domestic violence in their families. We also hold this idea of self-defense so dearly. It really came to the crosshairs of those two issues.”

Amanda Ross, Wilkens’ niece and her staunchest advocate, has spent the past two years working with Oklahoma Appleseed to advocate for the law. She recalls being devastated when the legislature failed to pass the 2023 bill. “It was a terrible feeling, to not be heard by your state leaders,” she told Bolts.

Ross was elated when the legislature passed the next bill, but then the governor’s veto felt like a “gut punch.”

Now, she’s hoping that the newly signed law will finally bring her aunt home after spending nearly half of her life behind bars. “My aunt wasn’t believed at so many points through the criminal justice system,” Ross told Bolts. “It took legislation to have hope again and this is even better, because it will help so many more criminalized survivors.”

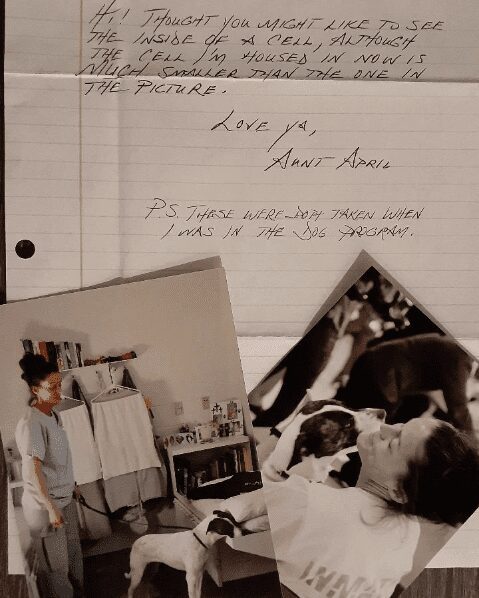

Wilkens that says she and the prison law library clerks have already put together packets about the new law, including a survey for those seeking representation and the address to write to advocates at Oklahoma Appleseed. Even so, she remains inundated with people coming to her cell to ask about it, prompting one of the clerks to post a sign on her door directing women to the law library for answers.

Still, Wilkens doesn’t mind the barrage of questions. “For so many years I was overwhelmed and caught up in the injustices in my own case,” she said. “When I was finally able to start advocating, I can’t tell you how freeing and how healing that was for me.”

Wilkens insists her fight will not end with the new law and her own freedom. “I will not give up the fight to free criminalized survivors here and everywhere,” she said this week. “I want to help get similar laws passed across the nation. Getting it done in such a tough-on-crime, law-and-order state as Oklahoma proves it can be done in any state.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom: We rely on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.