Civil Rights Attorney Vies to Pick Up the Torch of Reform Prosecutors in Massachusetts

Rahsaan Hall’s challenge to Plymouth County DA Tim Cruz, a longtime reform critic, is November’s defining battle for criminal justice policy in the state.

| October 6, 2022

On the dreary morning of the final day of summer in Brockton, Massachusetts, the only majority-Black city in New England, civil rights attorney Rahsaan Hall stood as a guest speaker before a couple dozen students in a community college classroom and turned on the theme music of “Law & Order,” the popular legal drama.

He got the room grinning and then paused the song. “This show made me crazy,” said Hall, who used to be a prosecutor and is running for district attorney this fall in Plymouth County. “It didn’t look anything like the reality I was dealing with on a day-to-day basis.”

Hall spent the next hour fleshing out what frustrates him about the disconnect between what prosecutors do on the TV show and the reality of the criminal legal system. He argued it’s outrageous that people are kept behind bars because they’re too poor to make bail. He highlighted glaring racial disparities in the Massachusetts prison population. He railed against mandatory minimum sentences for people convicted of drug-related offenses.

Those problems persist, Hall added, in large part because of the real-life versions of Law & Order’s righteous characters. “There are a whole host of things that DAs stand in opposition to that are trying to make the system better for everyone,” he said. “But they consistently say no.”

Some Massachusetts prosecutors took a different, more progressive approach in recent years. The 2018 election saw watershed victories for reform-minded candidates Rachael Rollins in Suffolk County (Boston) and Andrea Harrington in the Berkshires. They pushed far-reaching changes, for instance by teaming up and testifying in the legislature in favor of raising the age of juvenile prosecution to 21. At home, they decreased the prosecution of low-level offenses that stem from poverty, substance use, and mental health.

But neither Harrington nor Rollins will be in office come 2023, weakening the clout of reform proponents in Massachusetts.

Rollins was promoted U.S. Attorney by President Joe Biden, and confirmed by the Senate in December, a first for her cohort of so-called progessive prosecutors. But that created a vacancy in the DA’s office. Governor Charlie Baker, a Republican, replaced her with Kevin Hayden, who has since rolled back some of her signature policies. Hayden beat a progressive challenger beset by assault allegations in a Democratic primary on Sept. 6. That same day, Harrington was ousted in a Berkshire County primary, losing to a trial attorney who faulted her for pushing reform too far and not prosecuting some drug cases.

This has left Massachusetts progressives orphaned when it comes to local prosecutors, at least for now. It’s “really kind of sad,” said former Rollins staffer Nasser Eledroos, who is now managing director of the Center for Law, Information and Creativity at Northeastern School of Law. “We’ve won the creation of a large body of research supporting progressive policies, but, in terms of electoral power, we have in many ways regressed.”

Hall is hoping to reignite the reform torch in November by taking over the DA’s office in Plymouth, a county south of Boston of roughly 530,000. He is challenging longtime Republican incumbent Tim Cruz.

“The voices that would normally push for these types of reforms within the system aren’t there,” Hall told Bolts. “I see it as my responsibility and duty to be, for lack of a better phrase, the voice crying out in the wilderness saying that there is another way,” he added.

“There’s a more just, a more fair and more equitable way to deal with harm and disruption in community that doesn’t overcriminalize and overburden people–particularly poor people and people of color–and still find ways to make sure people are safe and healthy,” he said.

This is not Hall’s first run-in with Cruz. The ACLU of Massachusetts sued the DA’s office last year, challenging its demand that the ACLU pay $1.2 million to obtain public records that Hall had requested over prosecutorial policies and racial disparities; Cruz ended up releasing the records for free, an ACLU spokesperson said.

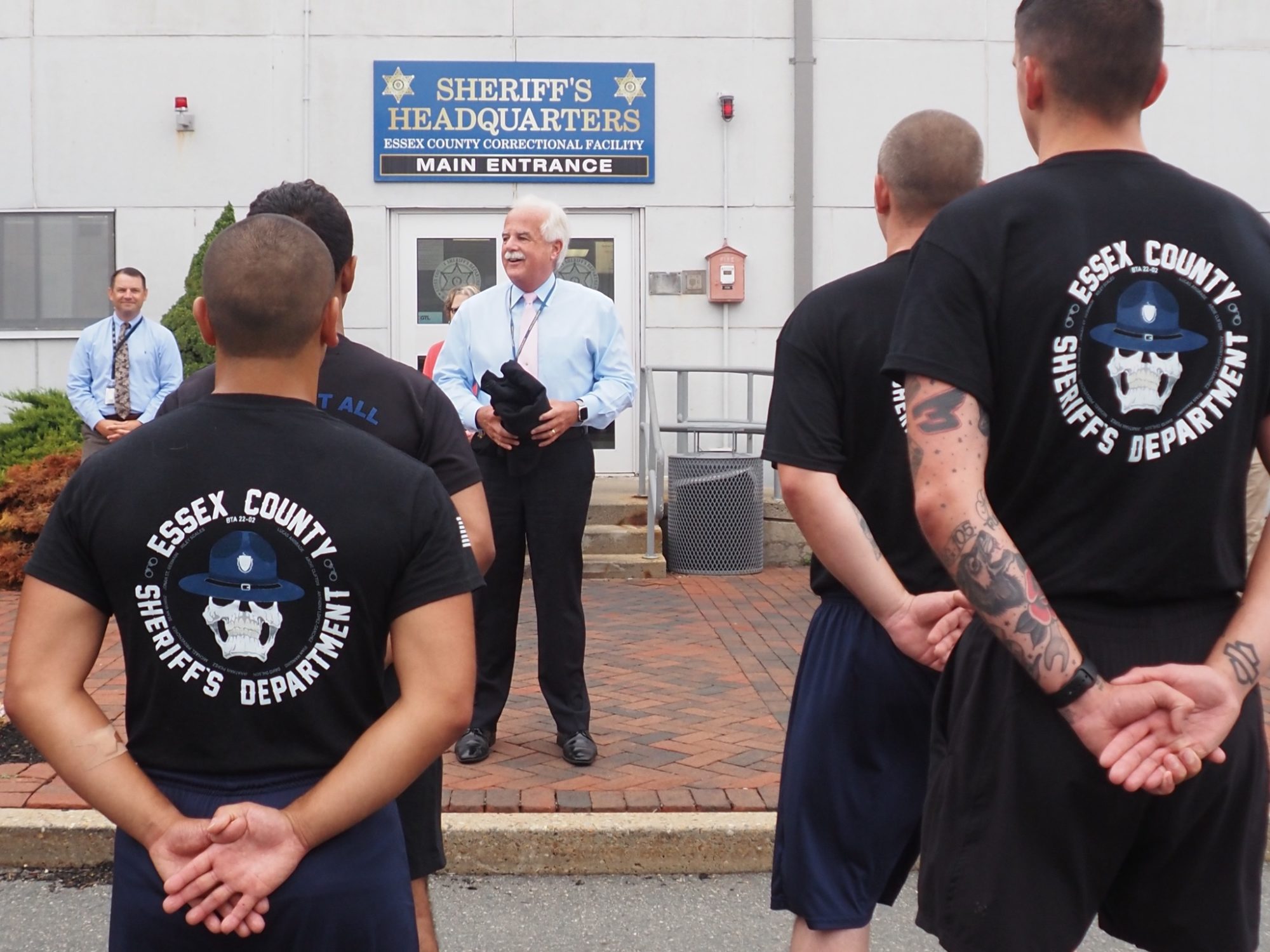

Over his 21-year tenure as DA, Cruz has been a stalwart opponent of progressive reforms and, after 2018, he emerged as a determined antagonist to Rollins.

“They talk about reimagining criminal justice, and I say this: you don’t have to reimagine anything,” Cruz said on a talk radio program in August. Data collected by the Vera Institute for Justice shows that Plymouth County’s prison admission and incarceration rates are higher than the rest of the state.

Early in the pandemic, Cruz fought the release of medically vulnerable people from jails and prisons–a position Rollins denounced as inhumane; the Plymouth jail suffered COVID outbreaks amid broader complaints about detention conditions. In 2020, Cruz also mounted an unsuccessful effort with three other DAs to intervene in a Boston case where Rollins was looking to increase the age below which youth cannot be sentenced to life without parole. “It seems nowadays the defendants are being treated as victims, and the victims are invisible,” he said. Despite this tough-on-crime persona, The Boston Globe reported in 2015 that Cruz faced a staff revolt for making deals with defendants accused of violent crimes to secure their collaboration in other cases, including using public funds to bail someone out of jail.

Neither Cruz’s office nor his campaign responded to requests for comment from Bolts.

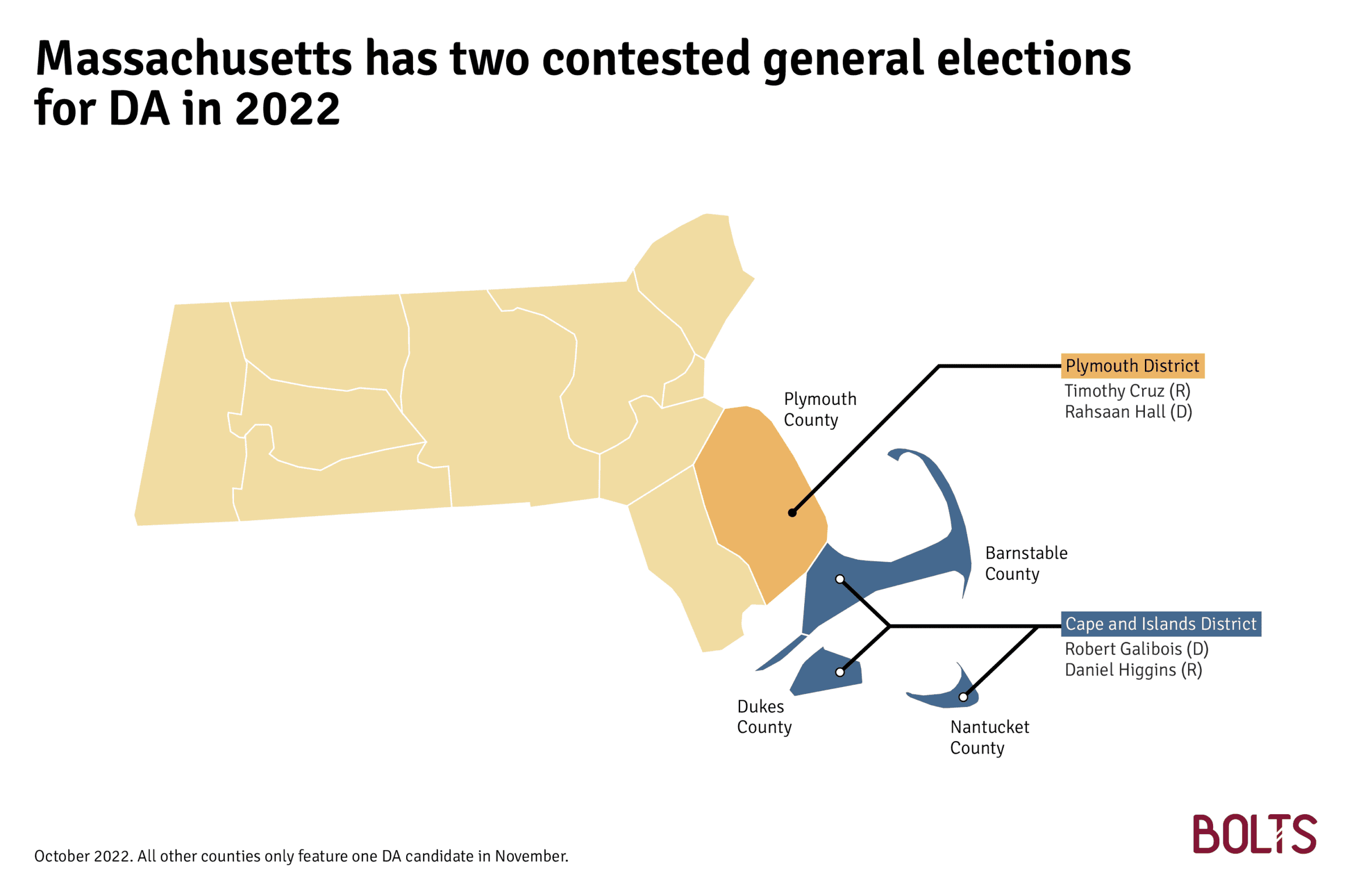

Another DA who played a lead role in criticizing Rollins’s approaches, Michael O’Keefe of the neighboring Cape and Islands district (Barnstable, Dukes, and Nantucket counties), is not seeking re-election this year. O’Keefe allied with Cruz, and also denounced Rollins’s “decline to prosecute” policy in the press, saying she was overstepping her role. Democrat Robert Galibois and Republican Daniel Higgins, who is endorsed by O’Keefe, are facing off in that district. Cape and Islands and Plymouth are hosting the only two contested general elections for DA anywhere in the state.

But it is the Plymouth race that has become the primary concern for state progressives, including prominent public officials. Hall is notably endorsed by U.S. Senators Ed Markey and Elizabeth Warren.

Plymouth voted for Biden in 2020 by 17 percentage points. But in this deep-blue state, the county is more prone than others to voting for a Republican. It is the only county that Warren lost in her 2018 Senate race, by one percentage point. Hall is also defying the weight of incumbency: Cruz has already won five elections.

In fleshing out his platform, Hall says change on some issues would have to wait. He told Bolts he believes that cash bail should eventually be banned but also that the general public is not ready for that step yet so he’d want to approach the matter “more pragmatically.” This would mean requesting cash bail in certain cases, he says, but also taking “gradual steps” toward its elimination. (Rollins faced severe criticism from court watchers over breaking a campaign promise to end cash bail.)

But he is also embracing Rollins’s signature reforms. Rollins made waves during her run for Boston DA when she rolled out a list of 15 low-level offenses that she would by default not prosecute, such as low-level drug possession or breaking into a vacant property; she argued that those behaviors should be addressed through other public services, an approach that has since spread elsewhere.

Hall says he, too, would establish a list of charges that his office would have a presumption of not prosecuting. These charges would include simple possession of all drugs and drug paraphernalia, driving-related offenses like driving with a suspended license, trespassing, and breaking and entering for the purpose of finding shelter. He estimates this would apply to at least 30 percent of charges being filed in a given year in Plymouth County.

“Many people, particularly in the city of Brockton, have been overburdened with the weight of this system,” Hall told Bolts. Hall makes the case that accountability and criminal punishment are too often treated as synonymous; he says he also wishes to expand restorative justice programs to reach resolutions outside the courtroom.

There is evidence that decline-to-prosecute policies have been conducive to public safety. Rollins’s team pointed to the declining rate of violent crime in Boston during her tenure. And a 2021 study by researchers at three different universities, who combed through two decades of data in Boston, found that it reduces crime when prosecutors decline to prosecute low-level offenses. “Keeping these individuals out of the criminal justice system… seems to stop the path of criminal activity from escalating,” said New York University Professor Anna Harvey, one of the researchers.

Hall also says he would aggressively review past cases and seek to change sentences for people he determines have been unfairly prosecuted. He says he would look not only at those who are demonstrably innocent, but also at victims of overzealous policing, racial injustice, and constitutional violations. This would distinguish Hall’s approach from the “conviction integrity units” proliferating nationwide, including in Cruz’s office, that typically focus only on innocence claims. (Some California DAs have created sentencing review units since a change in state law in 2019.) Even where “conviction integrity” units exist, they are rarely prioritized, says Daniel Medwed, an expert on wrongful convictions at Northeastern.

“It’s really hard to look back at your own decisions and think that your own decisions were flawed,” Medwed said.

Hall joined Medwed at a Boston bookstore on Sept. 21 to headline an event celebrating Medwed’s new book on wrongful convictions. Once a conviction is in the books, Hall told the audience, DAs offices often prefer keeping a case close to pursuing justice. “Just as a candidate for DA, the number of people who have reached out to me raising concerns about the wrongful convictions they’re trying to fight tells me how much of a problem this is.”

This is no abstract issue in Plymouth County. Two years ago, the lawyers for a woman named Frances Choy, who spent 17 years in prison after being convicted of setting her home ablaze and killing her parents, revealed serious prosecutorial misconduct in the case: false evidence, key witnesses never called.

In declaring a mistrial and freeing Choy, the judge in the case also cited racist emails by Cruz’s staff. One prosecutor wrote to a colleague that she would “show up (in court) wearing a cheongsam and will be the one doing origami in the back.” Other emails showed prosecutors mocking Asian stereotypes and jokingly using broken English.

Cruz declined to seek a new trial against Choy, and applauded her exoneration.

But critics stress that his office consistently avoids transparency. In 2020, one year before the ACLU’s lawsuit against Cruz, The Enterprise newspaper reported that his office does not keep what’s known as a Brady list, a tally of police officers whose records indicate potential credibility issues as witnesses in court to be communicated with the defense. Cruz’s office told The Enterprise that the office examines Brady concerns on a “case-by-case basis” and complies with the law, which does not require publication of the list.

Hall says he would publish it. He also said he would create and publish a “do-not-call” of police officers that he would never call on as a witness due to past misconduct; he said many on the Brady list would be on the “do-not-list,” though not all.

That would mark a break with the prevailing climate in Plymouth. One defense attorney who said he’d handled more than 300 cases in Plymouth County told The Enterprise in 2020 that local prosecutors there have a “symbiotic relationship with police.” As he seeks a sixth term this year, Cruz boasts endorsements from 34 different police unions.

Reform-minded candidates are often plagued by poor relationships with police and law enforcement once in office, and Hall says he’s trying to smooth things over up front. After announcing his candidacy, he said, he reached out to the police chiefs from all 27 communities in Plymouth County.

As of late last month, he told Bolts, “I’ve heard back from maybe four.”