Progressives Win in Seattle, Changing Directions on Public Safety

Voters ousted a mayor who oversaw a surge in encampment sweeps, and a Republican prosecutor who pursued punitive policies toward homeless people and drug users.

| November 13, 2025

In Seattle last week, voters shifted the political landscape toward the left. Progressive candidates swept the three city council seats on the ballot, growing their presence from one to three on the nine-member body. In the election for city attorney, Democratic challenger Erika Evans beat Republican incumbent Ann Davison, who’d pursued punitive measures during her first term, in a landslide.

And in the most closely-watched race, Mayor Bruce Harrell lost his bid for a second term against progressive challenger Katie Wilson. The race came down to the wire, with Wilson, a community organizer and novice to elected office, declared the winner by local media on Nov. 12 as she led with 50.2 percent of the vote.

Harrell and Davison both won in 2021 on promises to crack down on crime and homelessness coming out of the pandemic. But neither was able to repeat the victory this year, losing to Evans and Wilson who promised key changes to how the city approaches these issues, breaking with the incumbents’ more punitive practices.

This new wave of progressive leadership has taken on increased national visibility —Wilson has embraced the comparisons to Zohran Mamdani, the newly elected democratic socialist mayor of New York City—but they also stand to impact the lives of more than 800,000 Seattleites, in areas from housing to criminal justice.

“It is that battle between establishment, centrist corporate Democrats and more progressive Democrats,” said Crystal Fincher, a Seattle-based political strategist.

Subscribe to our newsletter

For more stories on local elections

In the mayoral race, Wilson and Harrell diverged greatly on a number of issues, starting with homelessness policy. Wilson was sharply critical of Harrell’s track record, including his unprecedented scaling up of homeless encampment removals. As Bolts reported last month, Seattle conducted more sweeps under Harrell than under his four mayoral predecessors combined.

Wilson told Bolts she’d curb these sweeps and pledged to roll out 4,000 new units of shelter over her first term.

Wilson and Harrell also differed in their approaches to creating more affordable housing. Wilson was relatively eager to levy new taxes on large corporations and the wealthy to pay for housing, compared to Harrell who had previously opposed such measures while in office. While both have advocated for more affordable housing, Wilson has embraced the Seattle Social Housing Developer, a city-owned startup designed to emulate Vienna’s social housing model, which involves a public developer building and managing housing that is designed to be permanently affordable for people with a mix of incomes.

In his first term, Harrell presided over the city’s recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, citing a rebound in downtown foot traffic and overseeing the completion of Seattle’s new waterfront park. Wilson, meanwhile, campaigned using her community organizing skills to paint herself as a straight shooter, willing to dive into policy details or be honest about the limitations of her proposed policies. She has also made resisting the Trump administration, including its immigration enforcement policies, a priority; Harrell unveiled executive ordinances to protect immigrants in October, though some observers criticized them as insufficient.

But one area where Wilson had more in common with Harrell was in handling the Seattle Police Department (SPD). One of Harrell’s priorities was replenishing SPD’s ranks, which were depleted after hundreds of officers left in 2021 and 2022. To accomplish this, he signed a new contract that increased officer base pay by 23 percent and offered hiring incentives of up to $50,000 for new officers.

Wilson has pledged to maintain funding for the department, shunning earlier calls she made in 2020 during the national Black Lives Matter protests for divesting money away from the police department. She has also promised to maintain the hiring bonuses.

At the same time, however, Wilson has shown support for the city’s Community Assisted Response and Engagement (CARE) department, a new non-police crisis response staffed by social workers. Currently, these alternative responders are required to be accompanied by police officers due to a provision in the police union’s contract with the city. Wilson has criticized Harrell for not sufficiently pushing back against the police guild’s demands and promised to make the CARE department more independent.

In late October, Harrell’s office signed a tentative agreement with the union that expands the CARE department’s personnel and powers; it’s unclear if the agreement will make it fully independent from SPD.

Fincher sees Wilson’s caution on policing issues as symptomatic of a wider belief that the topic is a weakness for the left compared to other issues like housing or affordability.

“What we’ve seen from campaigns on the left recently is that they’re afraid of being attacked on public safety; that they’re afraid of this ‘soft-on-crime’ attack,” Fincher said. “I think it’s unfortunate because we aren’t having a real conversation on public safety. We aren’t talking about prevention.”

The contrasts in the mayor’s race were magnified in the contest for city attorney, which featured the only Republican who holds city office in Seattle.

As city attorney, Davison has been in charge of prosecuting misdemeanors committed in city limits, with surrounding King County handling felony charges. These misdemeanor cases are overseen by the elected judges of the Seattle Municipal Court (SMC) and can range widely in severity from DUIs and domestic violence to petty theft.

Jazmyn Clark, the smart justice policy program director at the ACLU of Washington, said that because the Seattle City Attorney is the lone prosecutor at the SMC, it holds tremendous influence over the outcomes of those cases. Under Davison, about 5,000 to 6,000 misdemeanor charges have been filed in the court annually.

“The city attorney really gets to set the tone on how humanely the city of Seattle will be handling those particular offenses, and Ann Davison was very punitive,” Clark said. “We saw sort of a call back, or a return to more punitive, punishment-based sentences.”

Davison abolished community court, a program that offered people charged with misdemeanors resources and opportunities to have their charges dropped. She also compiled a list of repeat offenders for special emphasis in prosecutions due to their “high utilization” of the criminal legal system. Independent reporting found that the overwhelming majority of people on that list were homeless.

Perhaps most controversially, Davison spearheaded a crackdown on drug use and possession. After the state legislature downgraded the crime from a felony to misdemeanor in 2023, in response to the Washington State Supreme Court’s Blake decision, which struck down criminal statutes for drug use in the state, Davison lobbied hard for enabling legislation to prosecute possession at the SMC.

The following year, she also pushed for two new ordinances that introduced banishment zones for people suspected of committing drug or prostitution-related offenses. As Bolts reported earlier this year, the reforms gave judges the authority to bar people charged with certain crimes from entering certain areas of the city—and face misdemeanor charges if they do.

Clark believes that Davison’s tenure has been disastrous for the most marginalized Seattle residents.

“I think the last four years have just been incredibly harmful to communities of color and people experiencing poverty and homelessness,” Clark said.

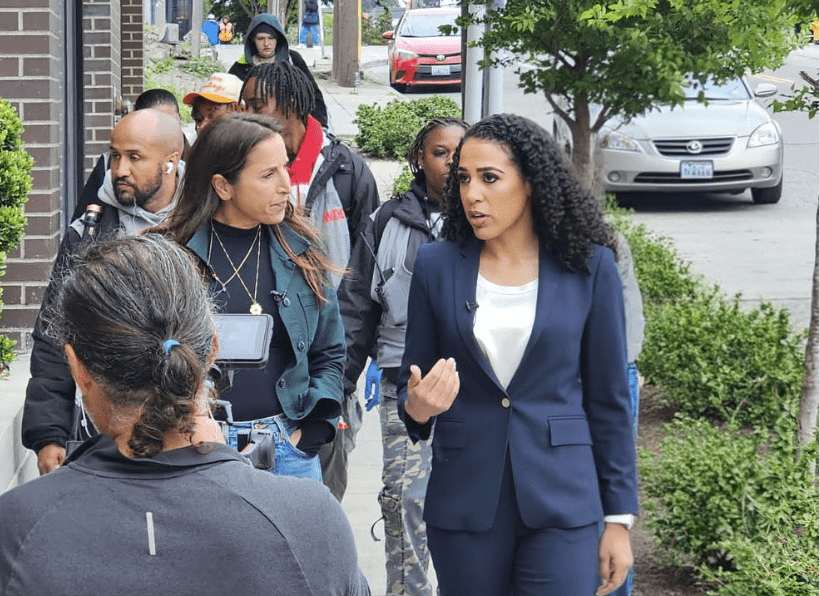

Challenger Erika Evans ran on reversing Davidson’s approach. She said she would deprioritize low-level crimes of poverty and addiction, and instead focus on prosecuting wage theft, DUIs and domestic violence charges. She also said that she wants to bring back community court, and that she wants to hold it in a place like a public library that defendants will experience as separate from the traditional criminal legal system.

In an interview with Bolts, Evans also pledged to decline to file any charges related to the banishment zones.

“We are not going to criminally charge someone with a new crime if they are in a banishment zone,” Evans said. “And so the court can still order that—I don’t have control over what the judges do—but what I’m saying is I will not criminally charge someone for being in an area they’re not supposed to be.”

Evans had told Bolts this summer that, “It’s really wild, crazy, and racist that our Republican city attorney did a lot of political grandstanding to think that this is a great idea, to bring something that we know is harmful and ineffective and racist back on the books.”

Evans has also promised to work with Lisa Daugaard, the founder of Law Enforcement-Assisted Diversion (LEAD), and prioritize housing, services and addiction treatment to those who end up perennially caught up in Seattle’s criminal legal system. She broke with other candidates she defeated in the August primary, though, in signaling that she was open to compelling defendants into treatment under threat of prosecution; other candidates said this would be counterproductive.

Evans believes that ultimately, it will be cheaper for the city to try to solve the underlying causes of why people end up in the municipal criminal legal system like poverty.

“What’s been happening is literally us as taxpayers paying for someone to get criminally charged, go through the criminal process, [to] pay for the cost for them to go to jail, which is expensive,” Evans told Bolts. “It’s $600 to book someone for just one day, and an additional $400 per day, and then for them just to be let right back out into our community without anything to get them what they need so they’re not dealing with those same issues again.”

Although progressives won across the board, the fact that they did so by very different margins indicates that at least some voters likely split their ballots, choosing both Harrell and other progressive candidates. For example, progressive Dionne Foster beat incumbent council president Sara Nelson by more than 25 percent, and Evans defeated Davison with roughly two-thirds of the vote, while Wilson just barely eked out a win.

City Councilmember Alexis Mercedes Rinck, a progressive millennial and the only Seattle official who ran for reelection this year to emerge victorious, thinks she and her fellow progressives won big this year because voters are hungry to hear a more direct and honest left-wing message from their representatives, particularly on issues of class and affordability. Mercedes Rinck received more than 80 percent of the vote.

“Billionaires have taken control of this country in ways we’ve never seen before, and it is hurting all of us,” Rinck told Bolts. “Progressives in Seattle who won spoke pretty unapologetically about that reality. We didn’t try to assuage people’s fears or gaslight voters that wealth inequality isn’t an issue.

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.