Sacramento Ballot Measure Pushes Policing to Address Housing Crisis

Housing advocates worry the measure would ratchet up law enforcement without providing enough shelter, shuffling more people through the criminal legal system.

| October 17, 2022

In November, Sacramento residents will be faced with a weighty decision not usually left up to voters: whether to broadly criminalize homelessness within the city. Measure O, a ballot measure brought by a group called Sacramentans for Safe and Clean Streets and Parks and supported by local business interests, would outlaw camping on public property, and allow individual residents frustrated by encampments to initiate abatement proceedings, effectively forcing the city to act on complaints. The city will also create new shelter spaces, but only a few hundred of them—a small fraction of the number of homeless people who will likely be displaced if the measure goes into effect.

Measure O is merely one of a series of recent efforts to crack down on homelessness in Sacramento. In late August, the city and county passed three separate ordinances to forbid camping in a wide variety of public places, including on sidewalks, in front of businesses, near “infrastructure,” and along the American River Parkway, a wooded riverside area where many unhoused people camp.

By now, it’s a familiar story across the state: cities vacillate between trying to offer unhoused people shelter and criminalizing them for lacking it—and increasingly, they do both at the same time. This push-pull dynamic is a result of cities attempting to comply with the letter of a 2018 appeals court decision holding that municipalities can only enforce anti-camping ordinances if they have shelter beds available—while doing as much as possible to bulldoze over the spirit of it. “The rhetoric is like, oh, it’s not as bad as you think it is. Or we’re gonna apply this in a really humane way, so don’t worry about it,” said Bob Erlenbusch, the founder of Sacramento Regional Coalition to End Homelessness. “But that belies the reality on the streets, you know?”

The cyclicality of the homelessness conversation in Sacramento has produced a profound feeling of déjà vu. Advocates decry the futility of trying to enact any policy that’s guided by the demands of housed people rather than the needs of unhoused people, involves criminalization, and lacks longer term solutions—condemning people to an endless cycle between streets, shelters, and jail. They fear that Measure O will only keep the wheel spinning. “The only thing you’re doing is finding ways to shuffle people through the hospital system, through the shelter system, through the prison system—and that shit costs a lot of money. A lot of money,” said Asantewaa Boykin, the co-founder of Mental Health First Sacramento, a civilian crisis response team that aims to get police out of mental health calls and works with many unhoused individuals. “We keep funding police to do Band-Aid work instead of finding solutions. I feel like I’m screaming at a wall.”

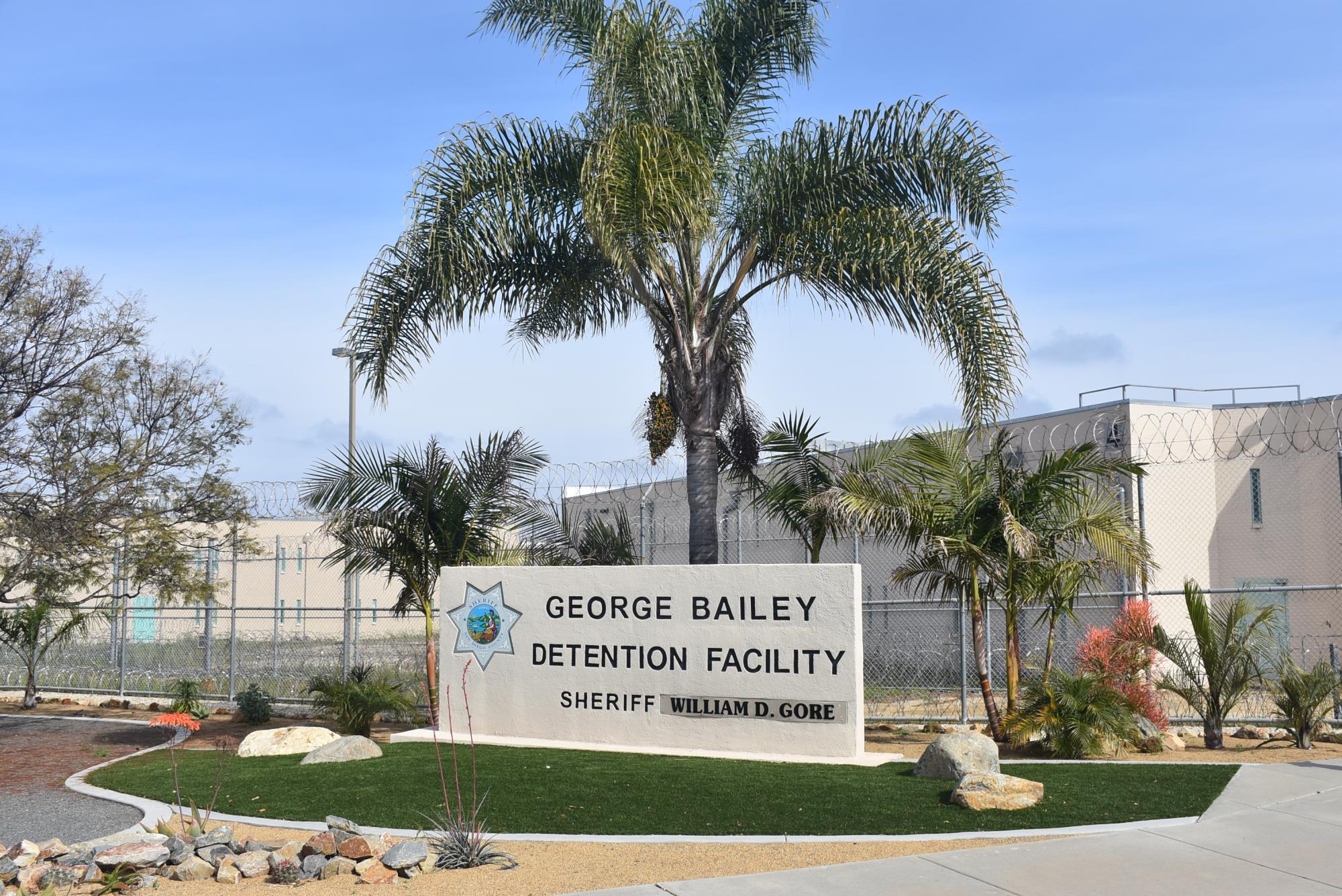

To Chris Herring, a professor of sociology at UCLA who has done extensive field research on homelessness in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and elsewhere, the “shelters vs. criminalization” debate is a false dichotomy between two things that have become fundamentally contingent on one another. This dynamic is on starkest display in San Diego, where Mayor Todd Gloria’s “progressive enforcement” campaign has directed police to arrest anyone who refuses shelter, which has produced an eightfold increase in arrests (the city’s shelter system generally hovers around a 93 percent occupancy rate). But it exists in some form in nearly every municipality across the state.

To fully understand why, you have to look back to the federal Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals’ 2018 Martin v. City of Boise ruling. The decision, which affected nine western states, should have been a victory for anti-criminalization advocates. Instead, it created a series of perverse incentives for cities trying to manage their homeless population and avoid getting sued. Rather than interpreting the ruling as a moral and practical call for the state to stop penalizing people who sleep on the street if it cannot even temporarily shelter them, many cities instead have conceived of shelter availability as a pretext for criminalization and engaged in legal gymnastics to technically comply with that requirement.

Herring has observed law enforcement setting aside shelter beds—keeping them empty despite the presence of people who are ready and willing to accept them—in order to have enough on hand to make enforcement legally justifiable. In San Francisco, he studied a new crop of shelters that opened throughout the city with the intent to offer lodging with no limits on duration of stay, better conditions, and fewer strings attached; the goal was to get people housed long term. But, as Herring recounts in his research paper “Complaint-oriented ‘services’: shelters as tools for criminalizing homelessness,” Martin v. Boise gave police more control over shelter referrals and ramped up turnover, causing the city to strategically worsen shelter conditions. “As they were tied increasingly to policing after Martin v. Boise, a number of them rolled back those offers,” he told Bolts. “So some of these places that opened up initially offering the ability for people to bring their pets [or] partners can no longer allow that.”

Municipalities have also seized on a single footnote in Martin v. Boise, which suggests that it may still be constitutional to forbid “the obstruction of public rights of way” regardless of available shelter,” to justify new enforcement methods. In Los Angeles, the city council implemented an ordinance, 41.18, that outlaws camping near schools, parks, and other public spaces, and has since expanded it; City Controller candidate Kenneth Mejia has estimated that the new restrictions make being homeless illegal in a full 20 percent of the city’s terrain. The legality of the recent Sacramento ordinances also hinges on that footnote. “Now they’re defining infrastructure really, really broadly, which includes schools and basically any building that the government owns,” said Erlenbusch.

Just last August, Sacramento Mayor Darrell Steinberg was boldly declaring a right to housing and introducing a comprehensive siting plan that would have designated 20 new locations across the city where homeless people could stay, ranging from emergency shelters to motel rooms to safe parking and camping grounds. Now, he’s endorsing Measure O. How did the city get from there to where it is now in just over a year?

“I think the mayor’s proposal for a comprehensive siting plan was a genuine effort to expand options, especially during a pandemic where it was obvious that congregate shelter was not the way to go,” said Erlenbusch. “Out of the eight city council members, only a handful took him up on it. But in the meantime, homelessness has doubled…Businesses are upset. Residents are upset. Advocates are upset. Homeless people are upset—because nothing’s happened.”

To Erlenbusch, it’s impossible to overstate the role that angry constituents have played in the city council’s flip-flop from housing to criminalization. “They all have had tremendous pushback from business groups, community groups, especially neighborhood associations, and you know, the mantra is almost universal: ‘Well, we’re not against homeless people. But not here,’” he said. “I don’t even call it NIMBY anymore. I call it BANANA: build absolutely nothing anywhere near anything.”

Katie Valenzuela is a Sacramento city council member who has repeatedly resisted efforts to ramp up enforcement. She described the backlash from constituents that led many of her colleagues to vote against a vehicle camping proposal seen as an early test of Steinberg’s ambitious proposal. Two of the safe camping and parking locations she identified for the siting plan failed, in large part because of community pressure, and she’s since weathered two recall attempts by constituents angry about her approach to homelessness (a third attempt is already underway). “I think some people hate the solutions almost as much as they hate the crisis,” she said, laughing ruefully.

Enter Daniel Conway, the former chief of staff to a previous Sacramento mayor, who approached city hall with an initiative that would have required the city to come up with around 6,400 shelter beds within 60 days of the measure passing. “Immediately when we saw the text, the word bankruptcy flashed across all of our faces because there’s no way we’d be able to do that that quickly,” said Valenzuela. “We don’t have that much land and we definitely don’t have any money.” A flurry of negotiations and modifications ensued. Under the significantly revised version that will be put to voters, the city must only create up to 600 new shelter spaces, and is only required to spend up to $5 million of its own money doing so, according to reporting by the Sacramento Bee. The enforcement aspect of the measure, however, stands.

“It’s not even shelter, it’s shelter spaces, which we’re interpreting as tents on a parking lot somewhere,” Erlenbusch told Bolts. “There’s no requirement that the shelter spaces be evenly dispersed throughout the city. So you’re going to see the same thing that we’ve seen: it will be in disenfranchised communities, low-income communities. It’s not going to be in East Sacramento. It’d be like putting shelters in Beverly Hills in LA.” (Conway did not respond to a request for comment for this piece).

The fracas also reveals profound disagreements between Sacramento city and county on homelessness policy. In August, the council amended Measure O to make its enforcement contingent on the completion of an agreement that would clarify each body’s duties and financial responsibility—meaning that if the measure does pass, which seems likely, there’s a high possibility that it won’t go into effect. “The only possible positive outcome, at least from the no side, is that it won’t become effective because the city and the county can’t get it together to come up with any kind of agreement,” said Erlenbusch.

While the city’s hand may be forced by Conway’s ballot measure, it’s entirely responsible for the recent ordinance that elevates blocking the sidewalk to a misdemeanor. At the last minute, Mayor Steinberg added a companion resolution stipulating that homeless people who violate it will not be jailed or fined “to the fullest extent practical.”

Boykin told Bolts she was skeptical of how the mayor’s attempt to restrict incarceration or fines to “extraordinary cases” would play out in practice. “Nothing leads me to believe that if someone’s tent is taken, and there’s some paraphernalia found, that the police won’t charge them for that. They might not catch the misdemeanor, but they’ll definitely catch the substance use charges,” she told Bolts. “It just continues to funnel people through systems so that they’re off the street for a minute, which pleases a lot of their constituents.”

Parallel battles around homelessness are happening all over California—and sometimes, it’s the same people writing the playbook. Conway, the architect of Measure O, is on the board of the LA Alliance for Human Rights, which in 2020 brought a lawsuit against Los Angeles County demanding that the county expand shelter and services—and require homeless people to accept them under penalty of criminalization. Groups that work on homelessness in LA are adamant that the alliance doesn’t represent them or their interests. “This settlement may be trumpeted as a win by Skid Row property owners and politicians who are looking no further than the next elections, but it’s the same failed approach the City has been investing in for decades,” the Skid Row community group Los Angeles Community Action Network said in a statement following the lawsuit’s settlement in April 2022.

A number of groups supporting Measure O also oppose stronger tenant protections and affordable housing expansion in Sacramento, which Valenzuela sees as evidence of bad faith. “Our 2,400 shelter beds county wide are full of people, a lot of whom are ready to move on to the next step but can’t find one because we have no housing or permanent supportive housing available for them,” the councilmember said. “I can call any of these shelters and ask any of these residents why they’re still there. And they’re all gonna say the same thing. I got the job at the restaurant or I got all my benefits and I can’t find any place. There’s no room for me.”

But building housing takes time, political will, and a lot of money. Ultimately, for Boykin, the most tragic and rage-inducing thing about the endless, circular homelessness debate is not that that money doesn’t exist. It’s that it’s tied up in the large percentage of the city and county’s budget that goes towards the Sacramento sheriff and police departments. “It’s extortion. I don’t know any other way to put it,” she said. “And then we go, but where are the resources?”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.