Controversial Sheriff with Right-Wing Ties Faces Voters in Washington State

Snohomish Sheriff Adam Fortney, who faced recall efforts after defying COVID orders and rehiring deputies with misconduct violations, is up against challenger Susanna Johnson.

Jessica Pishko | November 2, 2023

Editor’s note (Nov. 10): Sheriff Adam Fortney lost his reelection bid to Susanna Johnson on Nov. 7. To stay on top of local elections nationwide, sign up for our weekly newsletter.

In January 2020, just weeks after he was sworn in as sheriff of Snohomish County, in Washington State, Adam Fortney rehired a deputy the previous sheriff had just recently fired for an unjustified killing.

Ty Trenary, the sheriff whom Fortney defeated in November 2019, had only a month earlier terminated a sheriff’s deputy named Art Wallin for a 2018 shooting that killed Nickolas Peters, a 24-year-old who had fled from police in his truck. Trenary had determined that an investigation by a county task force showed Peters wasn’t enough of a threat to warrant being shot, and that Wallin violated department policies on chases and deadly force. The department also reprimanded Fortney, a sergeant in the department and Wallin’s supervisor at the time of the shooting, for not calling off the chase that ended with deputies cornering Peters and barking orders at him to turn off his truck and raise his hands. According to the county’s investigation, Wallin claimed his “Spidey sense” made him believe Peters had a gun before he fired twice into the truck and killed him; no witnesses saw Peters with a firearm, and detectives only found a pistol inside a green zipper case under the center console of his truck after the killing.

Fortney’s rehiring of Wallin came just weeks after the county settled a wrongful death lawsuit by Peters’ family for $1 million. Just a week after he brought Wallin back into the fold, Fortney also reinstated two more deputies who had been fired by the previous sheriff for violating department policy after an internal investigation showed them trying to cover up an illegal search. Fortney defended the reinstatements, telling local reporters soon after he took over as sheriff, “I’m the new sheriff, I get to weigh in on my guys’ discipline, bottom line.”

Those rehirings, as well as Fortney’s defiance of Washington State’s stay-at-home orders in the earliest days of the pandemic sparked multiple petitions to remove him from office by the summer of 2020, just months into his term, but those efforts failed to gather enough signatures to trigger a recall vote.

This fall, Fortney faces a heated battle to keep his post as sheriff. His challenger in the Nov. 7 election, Susanna Johnson, is a longtime veteran of the Snohomish sheriff’s office who left it in 2020 shortly after Fortney took over. She has gained support from many in local law enforcement, including five former Snohomish sheriffs who penned an open letter to the Everett Herald in October urging voters to pick her.

“Snohomish County needs a sheriff who is willing to tackle difficult problems, not with partisan rallies, self-serving videos and inflammatory social media posts, but with action,” the sheriffs wrote in their letter. “We need a greater focus on professionalism and common-sense safety solutions.”

The election is nonpartisan but Fortney is endorsed by local Republicans, and Johnson has drawn Democratic support.

In an interview with Bolts, Johnson said she decided to leave the sheriff’s office, where she had become a bureau chief, in 2020 and began to consider running to replace Fortney after he reinstated the deputies who’d been fired for lying and covering up a warrantless search. One of the deputies, Matthew Boice, was also president of the Snohomish County Deputy Sheriff’s Association, which endorsed Fortney in his 2019 race; Fortney, himself the union’s former president, was replaced by Boice when he stepped down to run for sheriff.

“It was not only an embarrassment to this agency where I grew up, but just to all law enforcement,” Johnson told Bolts. “There’s real and perceived bias issues within the agency,” she said. She worried that rehiring deputies with known histories of misconduct leads to communities being “terrified of the cops.”

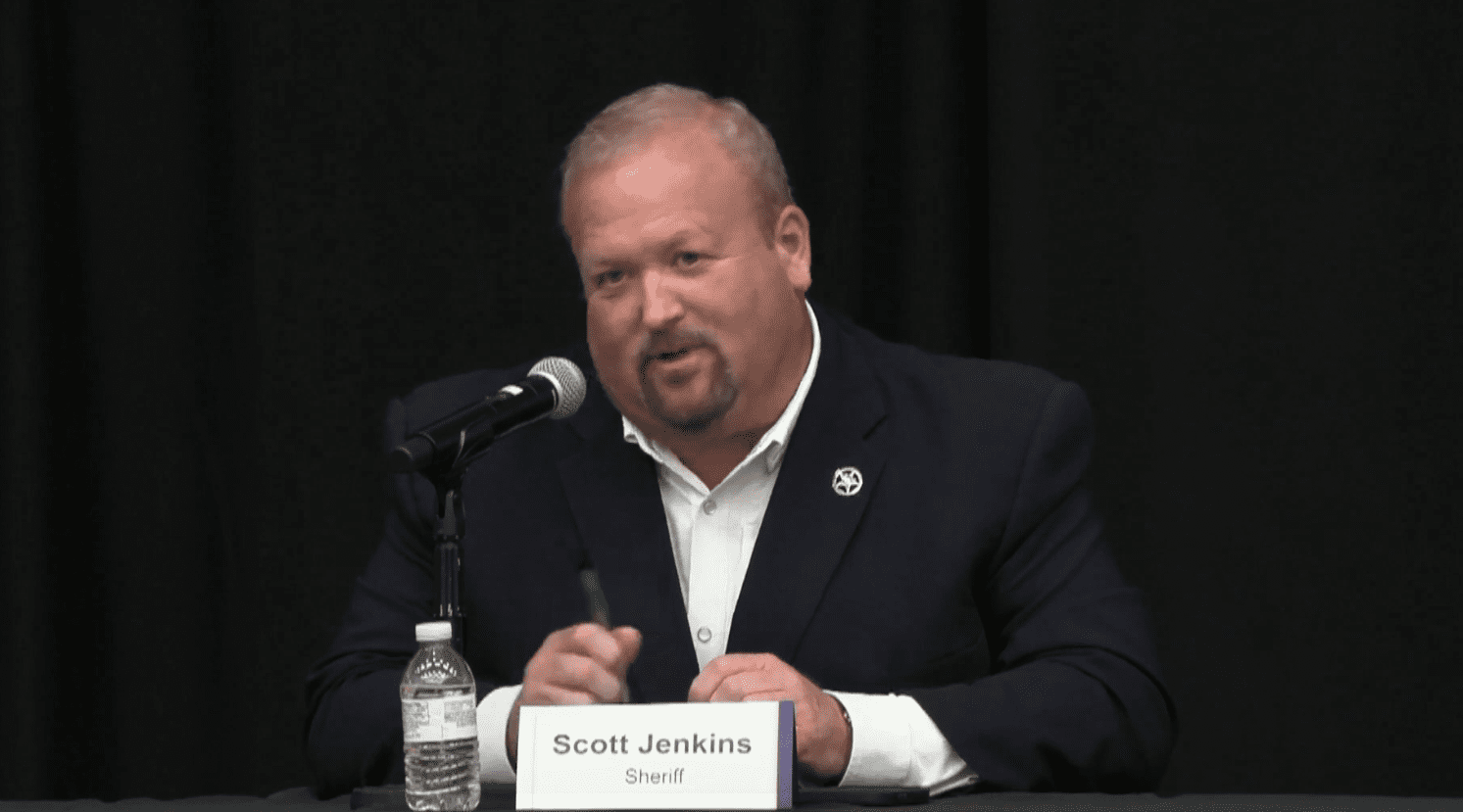

Fortney, who didn’t respond to an interview request or emailed questions for this story, has said he brought a different approach to the sheriff’s office, where he’s worked for nearly 30 years, much of it on patrol. “I ran as a graveyard patrol sergeant back in 2019 against a 6 year incumbent sheriff,” he said last month during a campaign forum held by the local League of Women Voters. “I ended up getting into politics when I was still a street cop, still a patrol sergeant running a crew, so I bring that perspective.”

In addition to bringing back deputies the previous administration had fired, other controversies clouded Fortney’s first several months in office. In March 2020, he wrote a Facebook post calling the actions of a deputy who chased and tackled a Black woman accused of jaywalking “reasonable”; the woman, who sued and accused the sheriff’s office of racial discrimination, recently received $75,000 from the county to settle the case. As COVID swept Washington State, Fortney again turned to Facebook to accuse Governor Jay Inslee of mishandling the crisis and vowed to refuse to enforce the governor’s emergency orders for nonessential business to close, to limit large gatherings and require masking indoors. As the pandemic continued, Fortney wrote an even longer post calling the governor’s orders unconstitutional and reiterating that he wouldn’t enforce them.

“As your elected Sheriff I will always put your constitutional rights above politics or popular opinion,” Fortney wrote. “We have the right to peaceably assemble. We have the right to keep and bear arms. We have the right to attend church service of any denomination.”

Fortney’s statements had consequences. At the height of the pandemic in the spring of 2020, a Snohomish barber said he was inspired by Fortney’s announcement to reopen his shop—no masks, no social distancing—to the chagrin of others in the community. Inslee’s chief of staff pushed back on Fortney’s refusal to enforce emergency restrictions, saying, “People should not be looking to the sheriff’s Facebook page either for constitutional analysis or health advice.” As Snohomish County health officials urged residents to follow COVID mitigation measures, the Snohomish County Executive Dave Somers said at the time, “This isn’t about the opinions of any single elected official…It’s about the health and safety of all the people we serve.”

After Fortney’s actions during the early days of the pandemic sparked efforts to remove him, the sheriff asked the county to help defend him and cover his legal costs to challenge the recall petitions. Adam Cornell, who was then the Snohomish County Prosecutor, refused, telling the sheriff in a letter that his statements were “fairly construed to support behavior that puts all citizens at greater risk of harm and death. Put simply, your words were akin to yelling ‘fire’ in a crowded theater.”

Cornell, who did not run for reelection in 2022, said that Fortney made it hard for people to trust law enforcement, including the prosecutor’s office, by rehiring deputies who had committed misconduct. “He forgot that he holds the public trust, and critical to holding the public trust is having to sometimes hold your own people accountable, however unpleasant that may be,” Cornell told Bolts. Cornell is now supporting Fortney’s opponent, Johnson, saying he believes she “doesn’t want to hold the office for her ego.”

A judge eventually found that the petitions to remove Fortney met the state statute requiring “malfeasance,” “misfeasance,” or “a violation of the oath of office” for recalling elected officials. But the group supporting the recall never got enough signatures to trigger a recall election, with organizers at the time stymied by the pandemic and ensuing lack of large gatherings like festivals and street fairs. The Washington State Supreme Court would later say that Fortney leveraged his position as sheriff to effectively nullify state law. “Fortney does not have the authority as Snohomish County sheriff to determine the constitutionality of laws,” Justice Mary Yu wrote in an opinion. “That is the role of the courts.”

Fortney has continued to court controversy as sheriff. In April of 2021, he hired a deputy accused of having ties to the Proud Boys who had been part of a crew of armed vigilantes who purported to protect downtown Snohomish from non-existent leftist agitators during rallies in the summer of 2020 after George Floyd’s murder. After local residents identified the deputy in a photo posted to the department’s Facebook page, Fortney initially defended him, writing in a December 2021 letter, “the evidence does not support any inference that you have engaged in discriminatory behavior, endorsed discriminatory behavior, or actively associated with any groups that endorse discriminatory behavior.” A month later, Fortney then changed his mind and fired the deputy, acknowledging in his termination letter that he had just recently opted to retain and not discipline him. “After further consideration, I believe I have misjudged the impacts this decision would have to public trust,” Fortney wrote.

This past summer, Fortney held a campaign event with Mark Lamb, the far-right sheriff of Pinal County, Arizona who is now running for U.S. Senate. Like Fortney, Lamb outspokenly defied the state’s COVID health orders in 2020 and has advocated for deregulation of firearms. The Everett Herald reported that Fortney grew angry and kicked a reporter out of his office for asking whether he agreed with Lamb’s politics.

Juan Peralez, president of the local community group UNIDOS, told Bolts that he was concerned about Fortney’s connection to far right politics and his role in growing the so-called constitutional sheriffs movement in the state. While Peralez has worked with other advocates for legislative changes to increase police accountability at the state level, he thinks that, ultimately, the sheriff’s office needs to change from within, which is why he supports Johnson. “Things are not going to change unless we have people inside the department who are going to do it,” he said.

In her campaign to unseat Fortney, Johnson has accused the sheriff of poor policing and policy-making, including management of the county jail. Fortney lifted booking restrictions early in the pandemic and encouraged officers to make more arrests after the population dropped at his jail, which has long struggled with understaffing and deadly conditions. In May, seven people incarcerated in the jail were admitted to the hospital as suspected fentanyl overdoses; it is not clear how the drugs got into the jail. Two people died in jail custody in September 2023.

The Snohomish County Corrections Guild has endorsed Johnson for sheriff, a switch from the 2019 election when the group backed Fortney. Derek Henry, the guild’s president, told the Everett Herald that the group flipped to Fortney’s opponent this year because he’s proven to be inept as sheriff. “In the 28 years that I worked in the correction bureau, it’s the worst that I have ever experienced when it came to nepotism and favoritism,” Henry told the paper.

If Johnson wins, she would be Snohomish County’s first female sheriff and one of very few female sheriffs in the country. She hasn’t focused on that aspect, however. “The only reason I’m running is because who’s sitting in that chair right now. And he needs to not be sheriff anymore,” Johnson said. “I’m only involved because, honestly, everybody’s intimidated by this guy.”

Stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.