Supreme Court Elections May Re-Open Gerrymandering Floodgates in Two Key States

North Carolina and Ohio’s high courts have blocked GOP gerrymanders with majorities that are vulnerable to flipping this fall, with mid-decade redistricting battles on the horizon.

Billy Corriher | March 24, 2022

State courts in North Carolina and Ohio blocked Republican efforts to draw districts that benefit their party this year, contributing to a fairer landscape for congressional races. But lawmakers in both states will get to draw new maps in the next two to four years rather than the usual ten, subject to review by new judges elected this fall. The GOP is strategizing to elect justices that will let them redistrict with less oversight.

Five supreme court seats are up for grabs this year across North Carolina and Ohio, and the results may once again open the gerrymandering floodgates in both states.

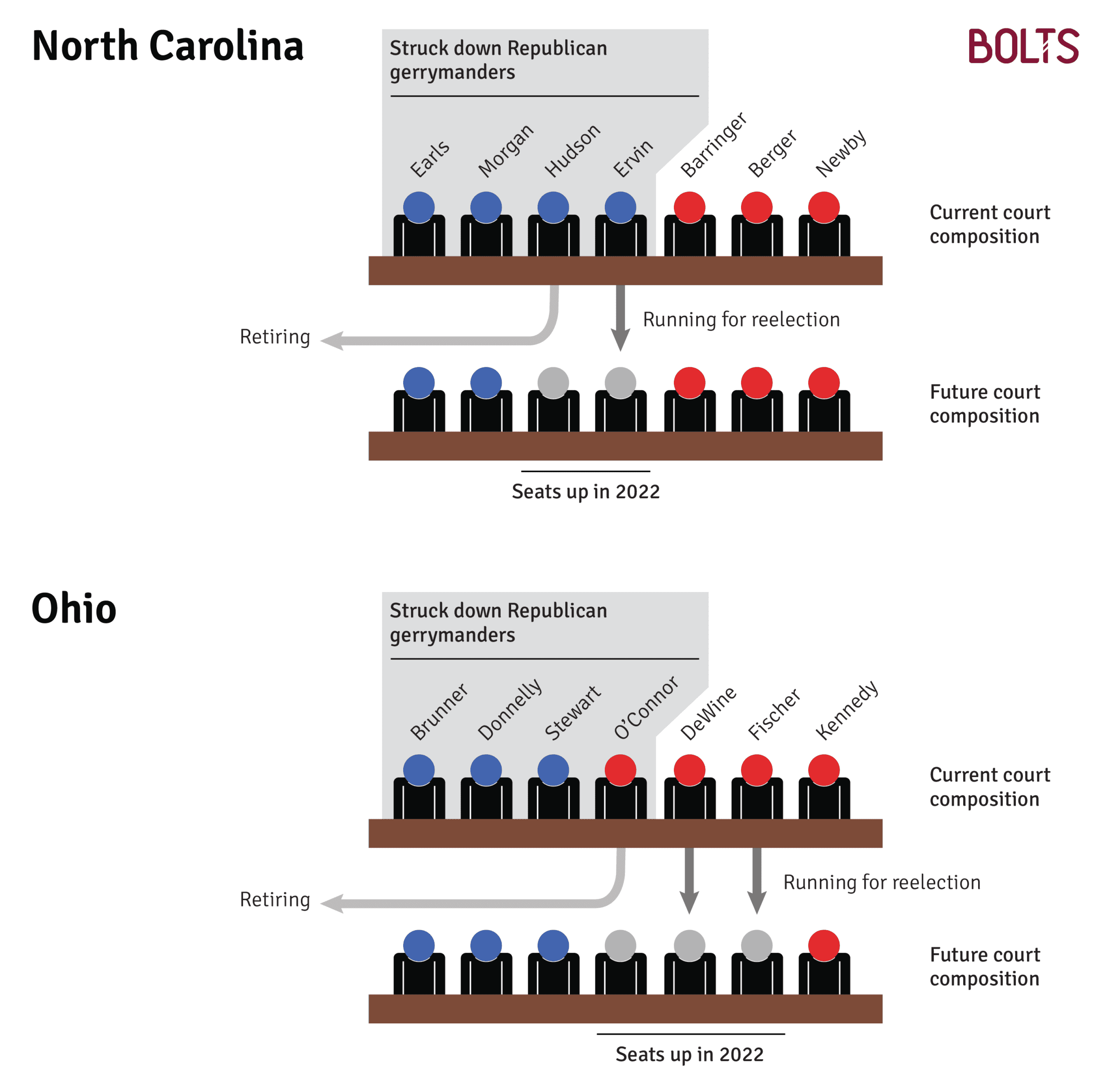

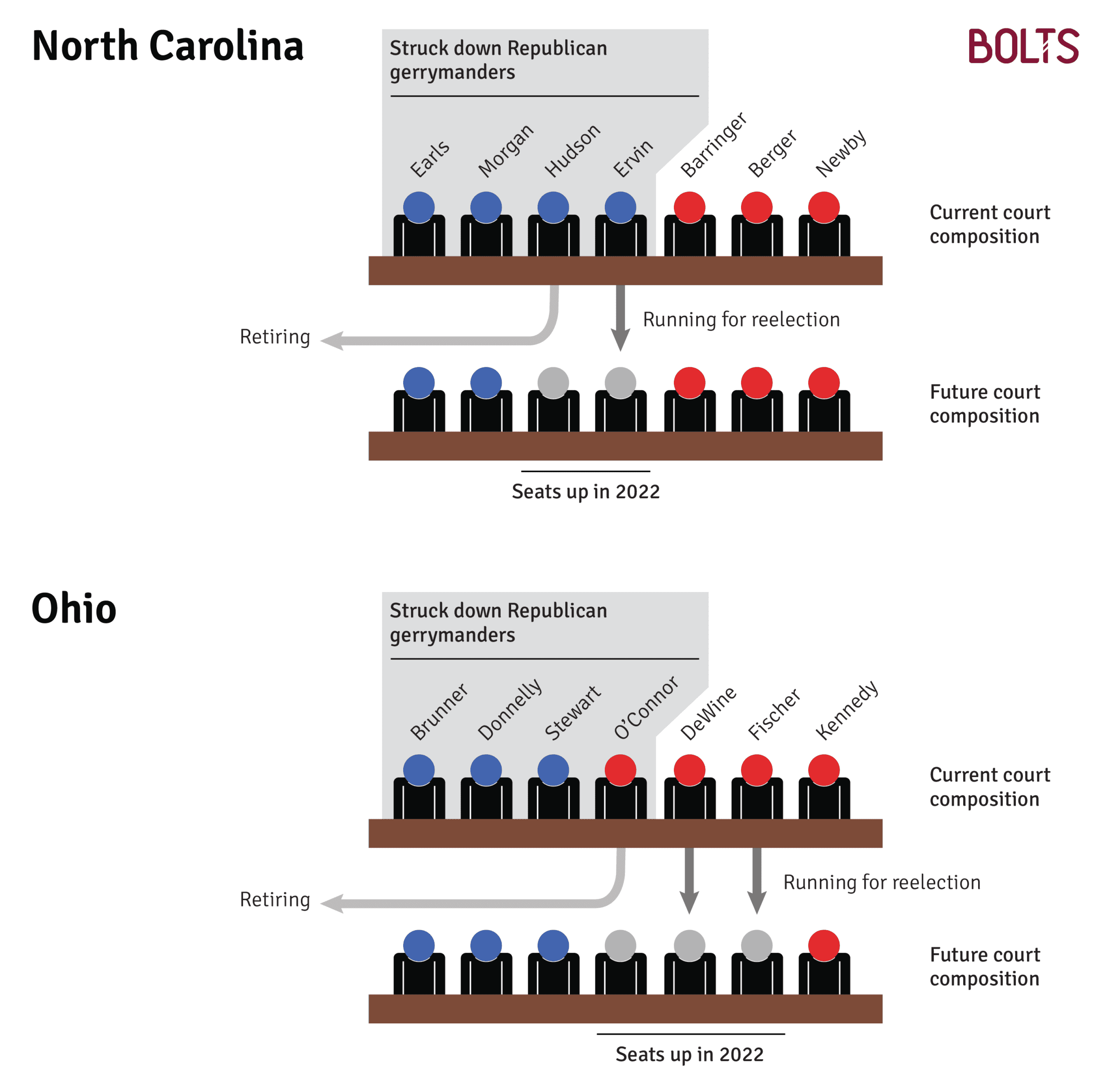

The rulings that struck down GOP gerrymanders in each state hang on narrow 4-3 majorities that are now highly vulnerable to flipping. To preserve the status quo, Democrats must sweep both seats on North Carolina’s ballot. In Ohio, they must win at least one of three races, possibly two. Republicans are jumping on the opportunity, in what is shaping to be a favorable cycle for them.

“We must focus on battleground state Supreme Court elections because so many redistricting fights are won and lost there,” former New Jersey Governor Chris Christie tweeted on Feb. 26, specifically naming North Carolina and Ohio. Christie is the co-chair of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, a group that aims to maximize the GOP’s redistricting advantage this decade.

Dee Duncan, the president of the Republican State Leadership Committee (RSLC), a national group that aims to win state-level elections, said the RSLC would be “spending more on state court races in 2022 than ever before.” The RSLC spent more than $5 million on judicial races in 2019 and 2020 alone, according to a recent report by the Brennan Center for Justice.

Democratic groups like the National Democratic Redistricting Foundation have also contributed money in judicial elections in recent years. But so far in Ohio, the GOP is far more mobilized. The three Republican candidates for the state’s high court have raised more than $1.1 million combined as of January, compared to the three Democrats raising under $190,000, six times less. The numbers were more equal in North Carolina, with a slight advantage for the Democratic candidates as of the end of 2021.

David Pepper, the former head of the Ohio Democratic Party, told Bolts that he thinks national Democratic leaders “should go all in to win these supreme court races.”

During Pepper’s tenure as party head between 2015 and 2020, Ohio Democrats flipped three supreme court seats, and redistricting played a major role in their messaging. When Democrat Jennifer Brunner won a supreme court election in 2020, her campaign sent her supporters an email with the subject line, “It’s official – we broke gerrymandering in Ohio.”

Those wins gave Democrats three of the court’s seven seats. Republican Chief Justice Maureen O’Connor, who had signaled her distaste for gerrymandering ten years ago, joined them in a string of rulings this year to make up a fragile majority that struck down the GOP-drawn maps.

“Gerrymandering is the antithetical perversion of representative democracy,” the court wrote. “When the dealer stacks the deck in advance, the house usually wins.” It ruled that the GOP-drawn maps did not conform to a constitutional amendment voters approved in 2015 to require fairer districts. Republicans on the Ohio Redistricting Commission have argued that the new constitutional standards of fairness are only “aspirational,” not mandatory, a claim that the court majority rejected.

But O’Connor, who is barred from running for re-election this year because of her age, won’t be on the court much longer. Her departure deprives Democrats of a rare Republican ally and forces them to win at least one of three seats on the ballot this year to compensate.

“With the retirement of the Chief Justice, it is imperative that a fourth justice that believes strongly in democracy is elected,” Terri Jamison, a lower-court judge and one of the Democratic candidates for supreme court, says on her campaign website, explicitly referencing the redistricting rulings.

But the chief justice race is likely to produce a new Republican justice no matter who wins because of who jumped in the election on the Democratic side. The only Democratic contender is Brunner, who is a current associate justice; she will face another associate justice, Republican Sharon Kennedy. Governor Mike DeWine, a Republican who signed the state’s latest gerrymanders, is favored to win re-election, will probably replace whoever wins, so even if Brunner becomes chief justice, her current seat will likely flip into GOP hands.

This means that, unless DeWine ends up appointing a Republican who bucks their party like O’Connor did, Democrats need to win one of the other two elections on the ballot in order to preserve the court’s latest redistricting rulings. Both involve ousting incumbents.

In addition to the open race for O’Connor’s seat, two Republican justices who opposed the court’s anti-gerrymandering rulings are up for re-election, Pat Fischer and Pat DeWine, the son of Ohio Governor Mike DeWine. Fischer now faces Jamison, and DeWine is challenged by Marilyn Zayas. (Neither Zayas or Jamison responded to requests for comment.)

Pepper says it nevertheless helps Democrats to have Brunner on the ballot, because she will boost the rest of her ticket. He argues that Brunner, who is a well-known former secretary of state, can appeal to moderate voters like O’Connor did. As partisan elections are often swept by one party, the idea goes, lifting the party’s fortunes in one race strengthens Democrats in the others.

Ohio Republicans changed election rules last year to add candidates’ party on the general election ballot. In the past, partisanship was not included for judicial candidates, and Republicans, who were reeling from their losses in 2018 and 2020, thought that this helped Democrats prevail in this red-leaning state.

In other states where courts have struck down GOP maps, Republicans are similarly looking to change election rules. The GOP cannot gain a majority on the Pennsylvania Supreme Court until 2025, for instance, but it is toying with a constitutional amendment that would change the way the state’s justices are selected.

In targeting the rules of judicial races, Republicans are borrowing from the North Carolina GOP’s playbook. Lawmakers there made supreme court elections partisan starting in 2018, and repeatedly tried to manipulate the electoral process. Despite the legislature’s efforts, Democrats have maintained a majority on the court for the last few years.

The North Carolina Supreme Court split along party lines on redistricting this year. Four Democrats voted to strike down; three Republicans voted to uphold. But two of those Democratic seats are now up for grabs, and Republicans need to win just one to have a majority next year. (In 2020, they swept three elections in the state, winning one seat by only about 400 votes.)

Republicans now have a shot at an open seat since Justice Robin Hudson, a Democrat, is retiring. Democrat Lucy Inman and Republican Richard Dietz, both lower-court judges, are facing off to replace her. In the second election, Democratic Justice Sam Ervin IV will face one of three Republicans—attorneys Trey Allen and Victoria Prince, and April Wood, a lower-court judge—who did not reply to requests for comment.

In exchanges with Bolts, Dietz and Inman each declined to share their views on redistricting, saying they would not comment on possible future cases. Both campaigns have faulted the other party for politicizing judicial elections.

Still, prominent North Carolina Republicans have signaled that they expect that a GOP supreme court majority would give them more leeway in upcoming years.

“Just a reminder that whatever Congressional maps are used this year can be revised next (and every) year by @NCGOP General Assembly which may have a GOP Supreme Court Majority,” Dallas Woodhouse, the former executive director of the state Republican Party, tweeted on Feb. 4, the same day the state supreme court struck down his party’s maps.

Following that ruling, lawmakers drew new legislative districts, and the supreme court imposed a new congressional map drawn by a bipartisan panel of three experts, all former judges. The GOP’s original map, which was struck down by the supreme court, would have given the GOP 10 of the state’s 14 seats. The new map has at least six Democratic-leaning seats.

But this fairer congressional map will only be in place for one election. There will be another round of congressional redistricting after the midterms that will determine the fate of multiple U.S. House seats, and it’s the new state supreme court elected in 2022 that will review the new districts.

The new legislative districts are more likely to last, because the state constitution says they “shall remain unaltered” until the next census. To pull off mid-decade legislative redistricting, state lawmakers would have to convince the high court to circumvent that ban.

Continued fights over redistricting are also guaranteed in Ohio. That’s because, if maps fail to garner bipartisan support, they are only operative for four years. The GOP has pushed maps all on its own, though they are currently locked in a stalemate with the court, which sets up a next round by 2025-2026. The latest congressional map drawn by the GOP there gives the party at least 11 of 15 districts, and the high court is reviewing it.

Republicans have a plan even if they fail to secure more favorable judges in North Carolina and Ohio: get the U.S. Supreme Court to silence state courts.

They are invoking a theory known as the independent state legislature doctrine, which holds that state lawmakers have carte blanche on redistricting and other election-related matters, free from any judicial review. The U.S. Supreme Court has so far sidestepped the doctrine, but four of its conservative members have signaled they are open to it.

Republicans say courts are the ones guilty of gerrymandering and of usurping the authority of lawmakers. The RSCL recently criticized Democrats for resorting “to state courts to change the rules,” and it vowed to “keep redistricting in the hands of the people.” But the state lawmakers of North Carolina and Ohio, who according to a growing number of conservatives should have sole discretion over redistricting, spent most of the last decade easily maintaining their majorities through heavily gerrymandered maps.

Kennedy, the Republican judge who could become Ohio’s chief justice in November, recently signaled conservatives’ determination to capture the court and undo its recent rulings. At a dinner hosted by a county Republican Party, she called redistricting “the fight of our life.”