Supreme Court Refuses to Empower State Legislatures to Run Elections as They Please

But the court also signaled in Moore vs. Harper that it wants a greater say in election cases, even those dealing with state law.

| June 27, 2023

In a much-awaited decision in Moore v. Harper, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected a once-fringe theory that was threatening to make its way into the mainstream of jurisprudence.

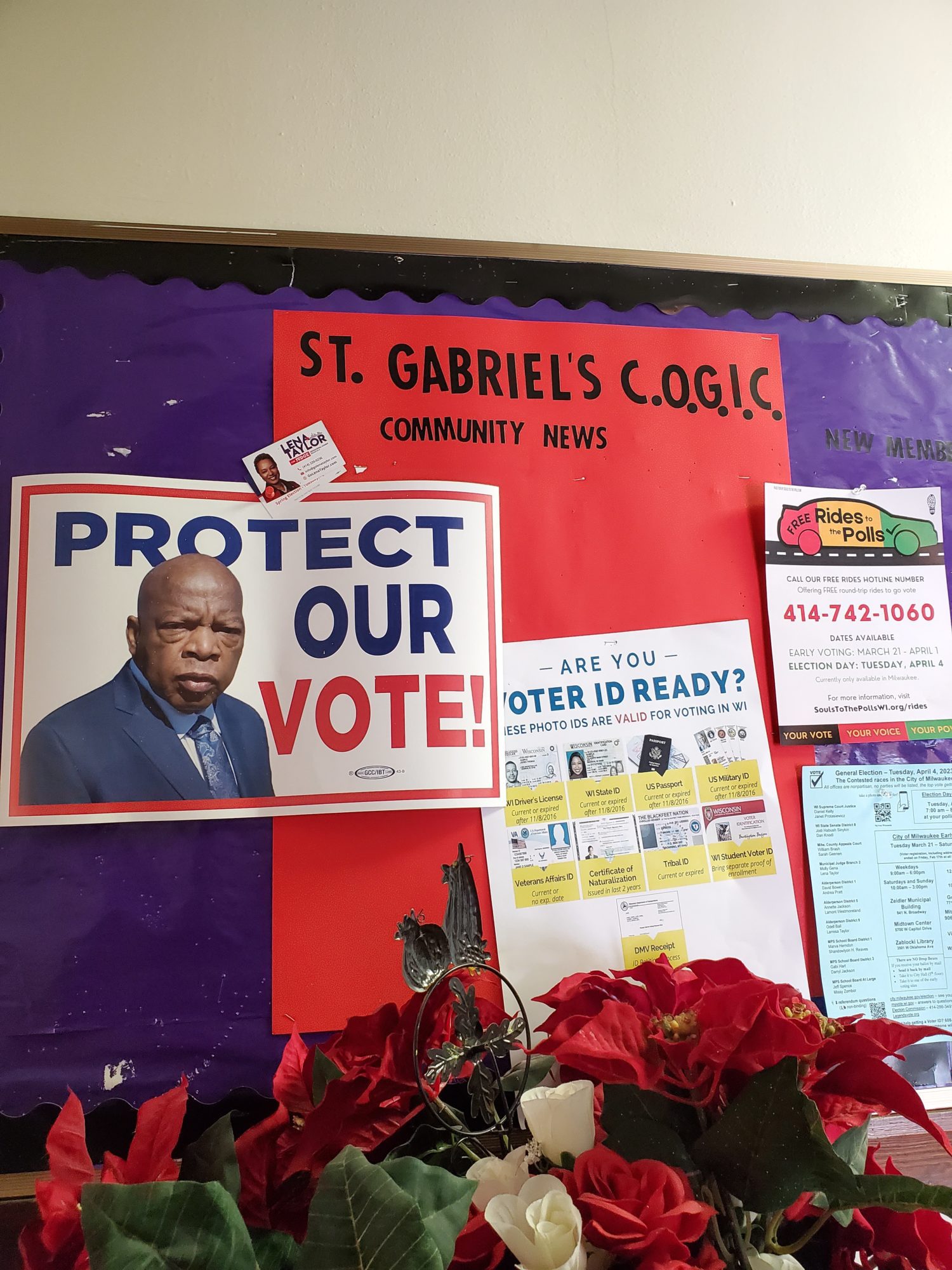

Known as the independent state legislature doctrine, the theory claims that the Elections Clause of the U.S. Constitution grants state legislatures near-total authority to regulate federal elections and draw congressional districts, and that no other institution can check them. Had justices embraced the doctrine, it could have drastically curtailed if not eliminated the ability of state courts to thwart lawmakers looking to suppress votes, gerrymander election maps, and subvert election results. It could even have sidelined governors, independent redistricting commissions, and other state officials from overseeing federal elections.

Instead, writing for a majority of six justices, Chief Justice John Roberts rejected the theory. “The Elections Clause does not insulate state legislatures from the ordinary exercise of state judicial review,” he wrote in a decision that’s largely focused on the power of state courts.

Roberts was joined by the court’s three liberal members, Justices Elena Kagan, Ketanji Brown Jackson, and Sonia Sotomayor, as well by Justices Amy Barrett and Brett Kavanaugh. Three conservative justices dissented.

Tuesday’s decision keeps alive high-stakes litigation challenging gerrymanders and onerous voting requirements in state courts, such as a lawsuit challenging Wisconsin’s congressional map that is expected to be filed once the state supreme court flips to a liberal majority this summer. Given the conservative bent of the federal bench, civil rights litigants have increasingly turned to state courts on all sorts of matters from abortion rights to criminal justice; an adverse ruling in this case could have gutted that strategy on voting rights.

Stuart Naifeh, manager of the Legal Defense Fund’s Redistricting Project, stressed his relief that his organization will be able to continue litigation on issues they cannot bring in federal courts. “The Supreme Court has affirmed that state courts are not barred from addressing critical issues, like partisan gerrymandering, which the Supreme Court held in 2019 that it did not have jurisdiction to consider,” he said in a statement, alluding to a ruling, also authored by Roberts, that partisan gerrymandering claims in particular cannot be brought in federal court.

He added, “By rejecting ISL theory, the Supreme Court has set an important precedent that state courts retain the authority to prevent suppression and protect their citizens from disenfranchisement.”

Still, Tuesday’s ruling came with a caveat whose full ramifications may not be known until 2024, if not later.

The fifth section of Roberts’ opinion stresses that the authority of state courts authority is not unlimited when it comes to regulating federal elections, and that the U.S. Supreme Court has an “obligation” to intervene to ensure that state courts do not “transgress the ordinary bounds of judicial review.” This language is vague as to how the justices will test this criteria, and when they might intervene. But in a break with usual practice, it hints that they may be more aggressive going forward in policing how state courts interpret their own state’s laws and constitutions.

In light of the right’s dominance on the federal bench, this caveat could end up undermining state courts as a fruitful alternative for voting rights litigation after all. And with the 2024 presidential election just around the corner, it is also creating new uncertainty for future election cases. One election law expert labeled it a potential “time bomb.”

The independent state legislature doctrine arose for the first time in recent memory in the litigation over the 2000 presidential election, but the doctrine’s visibility in conservative legal circles grew as state courts asserted a greater role in combating partisan gerrymandering, as well as in the aftermath of the 2020 election.

In late 2020, several GOP-led states asked the U.S. Supreme Court to block the certification of some states’ election results to help Donald Trump overturn his loss to Joe Biden. They argued that changes ordered by state courts in places like Pennsylvania, for example, had violated the U.S. Constitution because the authority to order those changes should have been reserved for lawmakers. This legal effort failed but some conservatives remained intent on further testing the doctrine.

When the North Carolina Supreme Court in 2022 struck down a congressional map approved by the state legislature as an illegal gerrymander, state Republicans invoked the independent state legislature theory and appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Voting rights advocates grew alarmed when it agreed to hear the case.

The federal court heard Moore vs. Harper in December, just weeks after control of the North Carolina’s supreme court flipped from a liberal to a conservative majority in the midterms, and the new court in early 2023 overturned the earlier rulings striking down the state’s congressional map. Some court observers thought that the U.S. Supreme Court may use this as an opportunity to declare the case moot, deferring the showdown over the independent state legislature theory to a future date.

But the 6–3 majority determined that the case wasn’t moot and proceeded to rule on the merits. Writing for the majority, Roberts pointed to a long string of precedents in which the U.S. Supreme Court has held that state legislatures’ power under the Elections Clause isn’t absolute. In the past century, Roberts detailed, the court has greenlit many instances in which the rules of federal elections have been set by actors other than state lawmakers. Those include voters using ballot initiatives to reject a redistricting proposal, a governor vetoing a map, and independent redistricting commissions drawing new congressional lines.

Roberts’s defense of independent redistricting commissions is especially striking since he wrote a vocal dissent in the 2015 case that tested their constitutionality. Roberts castigated Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s majority opinion in that case as “perform[ing] a magic trick,” and many thought the decision was under threat of being reversed. But on Tuesday Roberts seemed to have changed his tune and approvingly cited Ginsburg’s opinion.

Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Neil Gorsuch and only in part by Justice Samuel Alito, dissented on Tuesday. He argued the case should have been dismissed as moot but he also made a case for the doctrine on the merits. State constitutions, he wrote, “cannot control what substantive laws can be made for federal elections.”

Despite North Carolina Republicans’ failure to get their arguments upheld, Tuesday’s ruling brings no relief to the original plaintiffs who had challenged the GOP’s gerrymander. The new Republican majority on that state’s supreme court has given lawmakers there a virtual carte blanche in how they redraw maps, and the GOP is now widely expected to adopt a brutal gerrymander that could give them as many as four new congressional seats in 2024.

Moreover, many voting rights lawyers and election law experts are now expressing nervousness about Part V of Roberts’ opinion: This is the section that defies the typical deference that federal courts have shown to state court decisions that are grounded on that state’s own statutes and constitution. It carves out an exception to that general practice when it comes to federal election cases.

The U.S. Supreme Court can always receive appeals of state supreme courts decisions, but its typical practice is to not review the validity of rulings that are focused on state texts. Moore vs. Harper tweaks that approach. Citing the unusual opinion overruling the Florida Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore (this is the first time ever that a majority opinion has cited that case), Roberts’ majority opinion hints that his court will keep a more watchful eye on state judges.

The chief justice nods toward a soft version of the independent state legislature theory. “State courts may not transgress the ordinary bounds of judicial review such that they arrogate to themselves the power vested in state legislatures to regulate federal elections,” he writes. “The Elections Clause expressly vests power to carry out its provisions in ‘the Legislature’ of each State, a deliberate choice that this Court must respect.”

In practice, there is no way of fully anticipating what this means for future decisions, and whether the U.S. Supreme Court will step in only for extraordinarily rare cases or more frequently, until those cases arise. “The Court makes clear that it is not providing any standard at all—even an attempt at a standard—as to what this means concretely,” Rick Pildes, a professor at New York University School of Law, wrote on Tuesday.

The concern is that this ruling may give the conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court more room to second guess state supreme courts—and that this will be tested in the cases that are bound to arise in the midst of the crucible of the upcoming presidential election. Moore vs. Harper, writes Rick Hasen, a professor at the UCLA School of Law, “is going to potentially allow for a second bite at the apple in cases involving the outcome of presidential elections.”

Still, the U.S. Supreme Court’s rejected voting rights organizations’ worst fears, and these groups largely celebrated Tuesday’s ruling. This was their second court victory this month, after a decision earlier this month that salvaged what’s left of the Voting Rights Act.

Both cases could have thrown a major wrench into how U.S. elections are run but a majority of justices chose to mostly uphold the status quo.

“This is the second time this month that the Supreme Court has ruled in favor of protecting our democracy through voting rights,” Maya Wiley, president of The Leadership Conference on Civil and Human Rights, which filed an amicus brief in this case, said in a statement. “We will continue the fight to ensure all of us can participate in our democracy and hold accountable the elected officials who abuse their power.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.