Officials Play “Accountability Ping Pong” With Jail Deaths in Texas

A bipartisan push for more oversight comes after a sheriff flouted state law mandating independent investigations of jail deaths.

| April 22, 2025

A 40-year-old man died from dehydration in 2022 after being detained for more than two months inside the Tarrant County jail, one of at least three people with documented mental illness to die of thirst in the jail’s custody in recent years. Last year, another man, 57, who was deemed incompetent to stand trial for the charges that landed him in jail, died of sepsis from a bowel condition, after three months inside the county lockup.

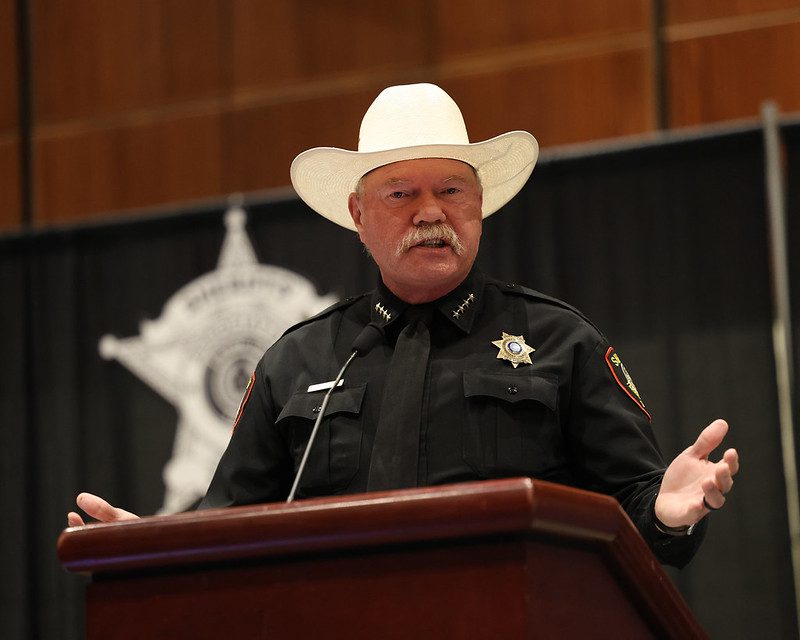

These were among the more than two dozen people who died in Tarrant County jail custody since 2021 whose deaths weren’t fully investigated according to state law. Family and friends of people who died in the jail have asked state officials to intervene after Bolts revealed last year that Tarrant County Sheriff Bill Waybourn had flouted state law requiring outside law enforcement investigations into all jail deaths—a key element of 2017’s Sandra Bland Act that was designed to keep sheriffs from investigating themselves when people die in their custody.

Instead of commissioning independent investigations, Waybourn’s office has defended the practice of sending its own internal investigations into jail deaths to the Fort Worth Police Department, and asking local police to “review” its findings. The sheriff’s office didn’t respond to questions that Bolts sent for this story, but it has previously pointed the finger at the state agency tasked with regulating county jails, saying state regulators never took issue with its handling of jail deaths during the three years that the independent investigations were not occurring.

After accusing the sheriff’s office of violating the law last fall in light of Bolts’ reporting, Texas jail regulators now say there’s nothing they can do about the failure to commission independent investigations into deaths in jail custody, which have spiked on Waybourn’s watch. At least 70 people have died in jail custody since the sheriff took office in 2017, compared to 25 deaths in the eight years prior.

Facing hands-off state regulators and a defiant sheriff, family and friends of people who died in the Tarrant County jail have continued to protest outside the county lockup in downtown Fort Worth and speak out at state and local government meetings. They’ve also appealed to Texas lawmakers, asking them to pass legislation mandating more transparency for in-custody deaths, and pushing back on proposals that would further limit investigations in Tarrant County and across the state.

“Transparency is the number one thing that I’m looking for,” said Faith Bussey, a Republican activist in North Texas and friend of Mason Yancy, who died in December after nearly four days in jail custody. “Because without it, I don’t think families are going to be able to trust the narrative that comes out of the sheriff’s department.”

Yancy’s death caused a stir in Texas conservative circles that have typically been a base of support for Waybourn, a Republican who was re-elected to his third term in November. Family and friends believe that Yancy, a 31-year-old activist who co-founded the prominent gun-rights group Open Carry Texas, didn’t get appropriate care for his diabetes at the jail. A medical examiner’s report states that Yancy died from “natural” causes due to a blood clot in his lungs.

Waybourn has defended his jail’s treatment of Yancy, telling the county commission in January that he saw medical staff repeatedly during his time there and that when he collapsed, “Life saving stuff was taking place immediately, within very few seconds.” This month, Yancy’s brother sent a letter asking the county commission to remove Waybourn from office, listing other deaths at the jail and citing a section of state law that allows for the removal of sheriffs for “incompetency.” “His incompetence regarding inmate deaths in the jail can no longer be tolerated,” the letter said.

Independent law enforcement investigations into jail deaths often shed light on dangerous conditions and neglectful treatment that can lead to preventable deaths. Since Texas started requiring them, these independent investigations have documented jail staff across the state ignoring people with deteriorating health, denying treatment for chronic conditions like heart disease and diabetes, and even mocking people who were dying and in pain. Even if they rarely lead to consequences for jail staff, these outside investigations often still document information that families need to pursue wrongful death lawsuits or uncover evidence that contradicts jailers’ account of what happened.

Michele Deitch, an expert on jail and prison oversight who directs the Prison and Jail Innovation Lab at the University of Texas at Austin, said these outside investigations are critical “so family members can have closure, so the public knows what is happening inside, and so that jail staff learn how these deaths can be prevented going forward.”

“Without an independent investigation, the public and policymakers would never know that the so-called ‘natural death’ was attributable to something jail staff did or didn’t do, and there would be no guidance as to how such deaths could be prevented in the future,” Deitch told Bolts.

After the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office listed the Fort Worth Police Department as the agency looking into jail deaths, Bolts filed a public records request last year seeking Fort Worth police investigations into county jail deaths. Last October, the department said it had no records of those investigations, with a Fort Worth police spokesperson saying, “I’m told that the Tarrant County Sheriff Department investigates those.”

Emails obtained through subsequent records requests by Bolts this year show how sheriff’s officials asked the Fort Worth Police Department to conduct an “independent review”—reviews that generally repeated basic information, like the length of time someone spent in jail custody or the cause of death that had already been determined by a medical examiner. Some of the review letters from Fort Worth police were dated months after the deaths occurred, even as recently as this year—months after Bolts first reported on the lack of independent investigations.

In one case involving a death ruled to be from “natural” causes that occurred in the fall of 2022, the police department apparently didn’t send its review letter to the sheriff’s office until this month, with the letter from a Fort Worth detective dated April 14, 2025 concluding that the sheriff’s office investigation was “consistent, thorough, and complete.”

Well beyond Tarrant County, loopholes and weak enforcement had already undermined accountability and led to an undercounting of deaths in jail custody. In 2019, the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, a governor-appointed commission tasked with regulating county jails in the state, issued a report detailing how sheriffs were already getting around the requirements in the Sandra Bland Act, which had just taken effect the previous year, by abruptly releasing sick people from custody right before they died. The agency again flagged the loophole in its annual report issued this February.

The state jail commission itself also seems to have violated the Sandra Bland Act for years by allowing sheriffs to pick who investigates them following a death, rather than the commission appointing the outside agency. Brandon Wood, director of the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, said that he hadn’t been aware of Tarrant County’s failure to seek outside investigations into jail deaths until Bolts’ reporting last October—despite his agency being copied on emails from the sheriff’s office stating the Fort Worth Police Department would conduct an “independent review,” according to records Bolts obtained this month.

After Bolts first informed him of the lapse last year, Wood said his agency could issue a notice that Tarrant County was out of compliance with state jail regulations if it did not change course—the first step in a regulatory process that could eventually snowball into the commission taking action against the sheriff.

But Wood’s position on the matter appears to have since changed. The February report by his agency reiterated that “simply conducting a review of the investigation conducted by the county jail in which the death took place” violated Texas law, but concluded that state jail regulators were nevertheless powerless to make local officials comply. “This does not meet the intent of the letter of the law and results in a situation that we are unable to initiate enforcement action as there is no provision in the statute to do so,” the report from the jail commission said.

“I do not have any administrative rule that would result in Tarrant County being issued a notice of non-compliance,” Wood told Bolts this month. He declined to comment further on Tarrant County’s years-long failure to follow the Sandra Bland Act or who was at fault, saying only that the state jail commission itself has started assigning outside law enforcement agencies to investigate jail deaths as of March—agencies that no longer include the Fort Worth Police Department. “The previous process that was in place has been reviewed and we’ve changed processes,” Wood said.

Krishnaveni Gundu, co-founder and executive director of the Texas Jail Project, says that the finger-pointing reveals a system of “accountability ping pong” which is enabled by the fact that so much of the process is opaque and hidden from public view. Making information about the death investigations and who is responsible for them more clear and open would help cut through the “chaos and confusion,” she says. “Had there been transparency in this whole process, would we have gone for almost three years not knowing that so many deaths had not been investigated?”

Gundu, who has been organizing with families and community leaders in Tarrant County for years, is supporting bills filed in Austin this year to mandate more transparency and oversight around jail deaths.

One measure filed by state Representative David Lowe, a former corrections officer and Republican who represents Tarrant County, would create an advisory committee to review in-custody deaths and make recommendations to reduce preventable deaths, while also mandating a detailed and publicly available annual report on deaths that occurred in county jails. Another bill filed by Salman Bojani, a Democratic House member who also represents Tarrant County, would mandate that death investigation records be maintained as vital state records. Nicole Collier, another Democratic House member from Tarrant County, also filed a bill to clarify that the Texas jail commission must appoint a third party law enforcement agency to investigate jail deaths, and require information about those investigations be published on the commission’s website. Collier has said that the legislation was prompted by the failure to conduct independent investigations into Tarrant County jail deaths.

Meanwhile, advocates are also fighting against other bills filed this year that would dramatically limit independent inquiries into jail deaths and allow law enforcement to investigate themselves after most deaths. Republican State Senator Brian Birdwell, whose district also covers Tarrant County, refiled a measure that Waybourn pushed for during the last legislative session to eliminate the mandate for independent investigations whenever jail deaths are determined to be from “natural causes.” Other proposed legislation that recently passed out of a House committee would require law enforcement agencies to create secret personnel files regarding allegations of misconduct that had not been substantiated, which would not be accessible to even other law enforcement agencies—including in the case of jail death investigations.

“Some lawmakers’ answer to preventable deaths in county jails looks like a cover up: limit independent investigations, limit public information, limit oversight, limit liability,” Gundu told Bolts.

Previous deaths in Tarrant County jail custody highlight the kind of cases that could see less outside scrutiny. While a medical examiner’s report concluded that Javonte Myers, 28, died of “natural” causes from a seizure disorder in the jail in 2020, an independent investigation by the Texas Rangers, the detective arm of state police, showed Myers had been left alone in his cell for hours, despite guards claiming to conduct regular cell checks. Two officers accused of lying about cell checks were indicted on charges of tampering with government records, and in 2023 Tarrant County agreed to pay $1 million to settle a lawsuit from Myers’ family.

In the years after the Sandra Bland Act required independent investigations for jail deaths, the Rangers conducted the bulk of them, including in Tarrant County. But that changed in 2021, after the Tarrant County Sheriff’s Office hired the Ranger who investigated the deaths of many people in the county jail, including Myers. That same year, the sheriff’s office tapped the Fort Worth Police Department.

A sheriff’s spokesperson told KERA and the Fort Worth Report last year that the office pivoted away from the Texas Rangers “due to the strain on their manpower and additional responsibilities placed on them regarding the Texas border.”

Waybourn isn’t the only Tarrant County official who has pushed to reduce independent investigations into deaths in jail custody. In late March, Tarrant County District Attorney Phil Sorrells sent the Texas Attorney General’s Office a request for a legal opinion that questioned whether the Sandra Bland Act’s requirement to investigate only pertains to deaths that occurred on jail premises. The vast majority of people who die in jail custody were typically pronounced dead in a hospital, according to state records, often after experiencing a medical emergency, suicide attempt, or drug overdose behind bars. In-custody deaths might also occur while a defendant is being transported to or from court, or in an ambulance on the way to a hospital.

Sorrells, a Republican and political ally of Waybourn, has helped the sheriff pursue conservative causes since being elected DA in 2022, like establishing a new county task force to police elections and voting. Tarrant County Judge Tim O’Hare, the Republican county executive, has ordered sheriff’s deputies to remove family members of people who died in jail when they confront officials at county meetings.

In the DA’s letter to the attorney general’s office last month, Sorrells echoed Waybourn’s argument to lawmakers last session, writing that the requirement to commission outside investigations into all jail deaths had created “debilitating staffing challenges” and saying it imposed “an unnecessary and unfair burden on county sheriffs and outside law enforcement agencies to investigate routine or noncontroversial deaths that do not occur within county jails but happen to befall inmates when they are merely in a sheriff’s custody.”

Sorrell’s office didn’t respond to questions for this story.

Family members of people who died in Tarrant County jail custody continue to pressure the state’s jail commission as they lobby lawmakers for legislation to ensure transparency. Cassandra Johnson, whose son Trelynn Wormley died of a drug overdose inside the jail in 2022 after being incarcerated there for months, has made a point to speak out at the jail commission’s quarterly meetings since finding out that his death never received an independent investigation. “I’m asking again, to do your job,” Johnson told commission members during their February meeting, as she held up a banner with photos of her son and his young daughter.

Family and friends of Mason Yancy, who died in December, also spoke at the February meeting, noting it had been months since the jail commission learned the independent investigations were not occuring. “Something is irrevocably wrong, and it needs to be investigated,” said his sister, Mallory Yancy. “When will this commission stop turning a blind eye to what is happening?”

His brother, Darren Yancy, appealed to Texas Governor Greg Abbott in a letter last month calling for the removal of Wood, the jail commission director. He also addressed bills filed this year that would limit investigations into jail deaths: “These proposed bills are designed to thwart the efforts of those seeking answers regarding concerns of abuse or death of their loved ones while in custody,” he wrote. “These are repugnant and have no place in the statutes of American society in 2025. They must be stopped.”

Sign up and stay up-to-date

Support us

Bolts is a non-profit newsroom that relies on donations, and it takes resources to produce this work. If you appreciate our value, become a monthly donor or make a contribution.