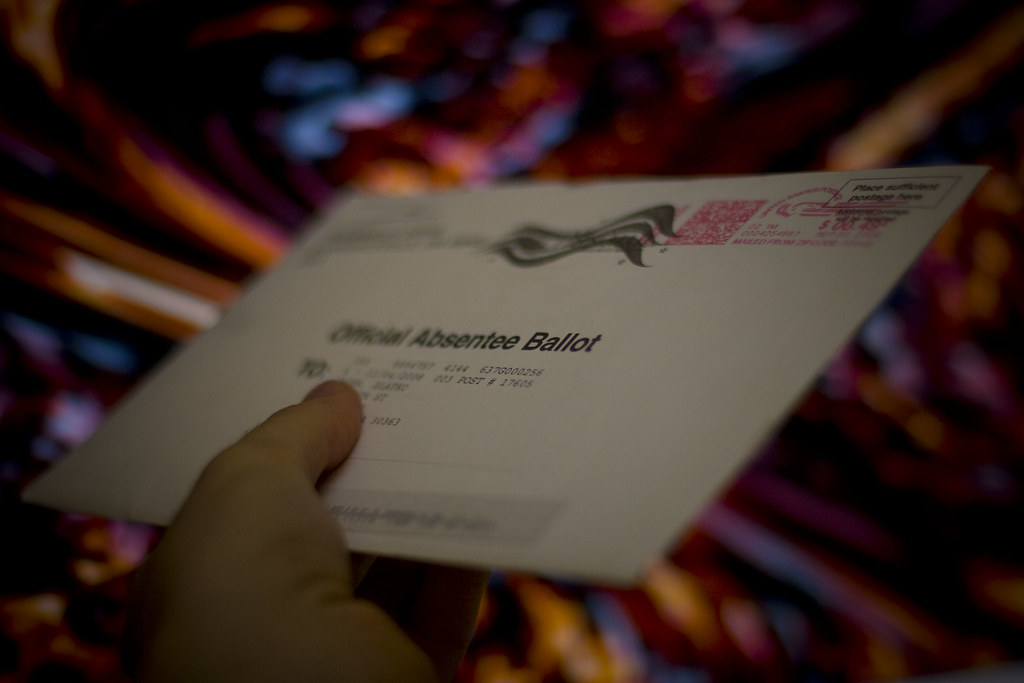

Virginia Makes It Easier to Vote by Mail

The state will no longer require an excuse when voters request an absentee ballot. Advocates say public authorities need to devote enough resources to facilitate mail-in voting and preserve alternatives.

| April 16, 2020

This article originally appeared on The Appeal, which hosted The Political Report project.

The state will no longer require an excuse when voters request an absentee ballot. Advocates say public authorities need to devote enough resources to facilitate mail-in voting and preserve alternatives.

Virginia has lifted the requirement that voters provide a reason for being unable to vote in person when they request absentee ballots.

This legislation, which was signed into law by Democratic Governor Ralph Northam on Saturday, could pave the way for a surge in mail voting in the 2020 general election. The bill passed mainly on Democratic votes; it also drew support from 12 Republicans, about one in five GOP lawmakers. President Trump has targeted mail-in voting in recent weeks.

Virginia is the 34th state to end the excuse requirement, but the first to do so since the novel coronavirus entered the United States. While lawmakers passed this reform back in February, its significance is magnified now that the pandemic has wreaked havoc on the electoral system, prompting calls for public authorities to urgently shore up mail-in voting and provide convenient alternatives to going to the polls.

Voting access advocates now want public authorities to devote enough financial resources for mail-in voting, and to preserve for other options, to ensure that no one is left behind.

Earlier this month, a huge spike in the volume of absentee ballot applications overwhelmed local Wisconsin officials. The GOP took advantage by successfully suing to deny voters additional time to return their ballots, even when they received them late. Other states may be faced with similar conditions this fall.

“The system is definitely going to be under stress,” said Liz Howard, counsel for the Brennan Center for Justice’s Democracy Program and a former deputy commissioner for Virginia’s Department of Elections. “Jurisdictions may need to buy equipment to help them process the incoming mail. They may need additional temporary staff, additional storage space, and/or space to process everything from the absentee ballot applications to putting together a package for every voter. You have to print all this material and make sure every voter is getting the correct ballot.”

A Brennan Center report published last week estimated that running free and fair elections in a pandemic will cost approximately $2 billion. “The federal government needs to play its part,” said Howard, who co-authored it. “Local election officials are going to do everything that they can, and there’s a critical need for additional federal investment in what they’re doing.”

To reduce the number of steps it takes to vote, some states are now sending every voter a ballot application—if not an actual ballot. The latter is already law in five states. Iowa’s secretary of state has said he may order it in his state as well this fall.

Virginia statutes provide the state’s election officials with the authority to “designate alternative methods and procedures” in the event of an emergency.

Edgardo Cortés, Virginia’s former election commissioner, now an adviser at the Brennan Center, told me he used this authority during his time in office to extend absentee voting due to a snowstorm. He believes that it authorizes Virginia officials to send every registered voter an absentee ballot application in the event of an emergency. He was more skeptical that this authority could extend to sending every voter an actual ballot. Christopher Pipper, the current commissioner, declined to respond to my questions on this. Some Virginia lawmakers have voiced support for automated mailings.

More specific concerns are already emerging toward Virginia’s absentee voting rules. The ACLU of Virginia has filed a lawsuit challenging the requirement that absentee ballot envelopes be signed by a witness; a similar rule provoked issues in Wisconsin. Moreover, Virginia requires that absentee ballots be received by Election Day. Last week, for the first time, Wisconsin counted ballots as long as they were postmarked by Election Day, even if they were received days later. (That is already the law in California.) Democratic attorneys are now suing Arizona to demand the same.

In any case, preserving in-person voting options is also crucial for people who need special assistance, who encounter problems with their registration, or who did not receive their ballot in time. Demos, an organization that promotes voting rights, filed a lawsuit against the state of Ohio for shutting down in-person voting nearly entirely, noting that this is likelier to harm Black and Latinx voters.

Tram Nguyen, the co-executive director of New Virginia Majority, a progressive organization, also warned that expanding vote by mail will be insufficient to include all voters.

“Many Virginians are facing housing uncertainty amidst this COVID-19 crisis, and as more people are becoming transient, we must also consider whether or not mail will be delivered to them,” she said. She also noted that if mail is sent automatically and returned as undeliverable, it may lead some voters to be moved to inactive status.

Many states now allow people to register to vote through Election Day, in part to enable as many transient residents to get on the rolls as possible. Northam just signed a law to enable same-day voter registration, but it will only be enacted in 2022.

The law that ends the excuse mandate will be effective much sooner, on July 1. This poses difficulties as well, though. Virginia still has elections scheduled in both May and June. The state has encouraged voters to apply for absentee ballots by checking the box “My disability or illness” as an excuse for COVID-19 concerns.

Cortés expressed optimism that states have enough time to avoid a meltdown like Wisconsin’s in the general election. “States have a lot of challenges in front of them but they can anticipate and they should be planning appropriately for that,” he said. “They can take lessons and prepare for November.”

One danger that Wisconsin flagged, though, is that some officials will not care to run elections smoothly if they think a meltdown will help their party; in Wisconsin, the GOP-backed candidate ended up losing the Supreme Court election despite the voting restrictions Republicans sued to protect, but turnout was still weaker in blue Milwaukee, and Black voters were disadvantaged.

In Virginia, at least, the flurry of voting laws adopted by the legislature’s newly Democratic majority — Northam also signed laws making Election Day a holiday, extending voting hours, and enabling automatic voter registration — indicates a drive to expand access to the ballot.

The article was updated with news of the ACLU’s lawsuit, filed the day after publication. Also: Virginia adopted another major election reform in April.